Abstract

This paper provides evidence on the effect of welfare reform on fertility, focusing on UK reforms in 1999 that increased per-child spending by 50% in real terms. We use a difference-in-differences approach, exploiting the fact that the reforms were targeted at low-income households. The reforms were likely to differentially affect the fertility of women in couples and single women because of the opportunity cost effects of the welfare-to-work element. We find no increase in births among single women, but evidence to support an increase in births (by around 15%) among coupled women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Alternatively, it has been argued that higher income is associated with demand for increased quality of children, implying a possible reduction in quantity demanded.

The scale and pattern of the changes are similar for lone parent families.

The assessment was made on the basis of the couple’s joint earnings even in the case of cohabiting couples.

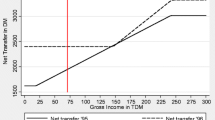

There was no attempt to present these reforms as revenue neutral: annual expenditure on FC/WFTC almost doubled between 1998–1999 and 2000–2001, from £2.68 billion to £4.81 billion in constant 2002 prices, with a further increase by 2002 to £6.46 billion.

Gregg et al. (2009) show that an important effect of WFTC was to mitigate the negative impact of moving into lone parenthood on employment and income.

Including the increase in support with payments for childcare.

The minimum school leaving age was raised from 14 to 15 from 1944 and from 15 to 16 from 1973.

We have replicated the analysis using a split based on household income and an interaction of household income and education. These alternative definitions of treatment and comparison groups produce stronger results, available on request.

See Hills and Waldfogel (2004) for a summary.

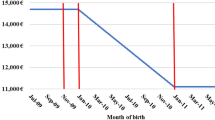

We choose end of June rather than end of July to allow for premature births.

Further reforms were made to the system of child-contingent benefits from this time.

It is not possible to do the analysis using official birth statistics because they do not contain information on education or income and, for unmarried or re-married women, on true birth parity.

Where this is missing, we randomly allocate a date of birth given the age of the child and the date of interview. This is the case for all births in the FES sample and 16% of births in the FRS sample.

Another issue that affects information on the number and ages of existing children at the start of the 12-month period (but not information on births during that period) is that older women may have had children who have now left home. We test the sensitivity of our results to restricting our sample to women aged 37 and under for whom this does not appear to be a problem.

This is measured as the total number of children a woman would have over her (reproductive) lifetime if she experienced the age-specific birth rates in a particular year.

The ethnicity information is fairly crude; we include indicators if the woman or her partner is Black, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani or other (non-White). Many of the recent births to women born outside the UK are to recent White immigrants from the eight EU accession countries (including Poland, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia). However, this wave of immigration occurred after the end of our period of analysis (beginning in May 2004).

The average estimated marginal effects from a probit regression are very similar, and these results are available on request.

One implication of this is that the reforms had an effect on the fertility decisions of households who were not (yet) receiving the benefits. However, McKay (2000, 2001) shows that there was a fairly high level of awareness of the new benefits even among those who were not receiving it, which may have come about as a result of the extensive television advertising and/or through word-of-mouth.

This differs to the specification in Table 3, column 4 both because of the longer period (1990–2003 compared to 1995–2003) and because there are no controls for ethnicity. The effect of excluding the ethnicity variables in the 1995–2003 sample is to reduce the coefficient from 0.0130 (0.0066) to 0.0120 (0.0066).

An alternative way of showing that there are no differential trends would be to test for placebo reforms in the pre-reform period. The effects of these placebo reforms—tested for each year of the pre-reform period—are not statistically significant.

Wages, house prices and unemployment are identified by Ermisch (1988) as important determinants of fertility.

References

Adam S and BrewerM(2004) Supporting families: the financial costs and benefits of children since 1975. The Policy Press, Bristol

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1999) Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1277–1365

Angrist JD, Pischke J (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Ashenfelter OC (1978) Estimating the effect of training programs on earnings. Rev Econ Stat 60:47–57

Baughman R, Dickert-Conlin S (2003) Did expanding the EITC promote motherhood? Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 93(2):247–250

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family. Enlarged edition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Berrington A (2004) Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Popul Trends 117:9–19

Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S (2004) How much should we trust difference-in-differences? Q J Econ 119(1):249–275

Blundell R, Costa-Dias M (2002) Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical economics. Portuguese Econ J 1(2):91–115

Blundell R, Brewer M, Shepard A (2005) Evaluating the labour market impact of the working families’ tax credit using difference in differences. HM revenue and customs working paper 4

Blundell R, Duncan A, McCrae J, Meghir C (2000) The labour market impact of the Working Family Tax Credit. Fisc Stud 21(1):75–103

Brewer M (2001) Comparing in-work benefits and the reward to work for families with children in the US and the UK. Fisc Stud 22(1): 41–77

Brewer M (2003) The new tax credits. IFS Briefing Note BN35. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Brewer M, Browne J (2006) The effect of the working families’ tax credit on labour market participation. IFS briefing note 69. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Brewer M, Duncan A, Shephard A, Suarez MJ (2006) Did working families’ tax credit work? The impact of in-work support on labour supply in Great Britain. Labour Econ 13(6):699–720

Ellwood DT (2000) The impact of the earned income tax credit and social policy reforms on work, marriage, and living arrangements. Natl Tax J 53(4):1063–1106

Ermisch J (1988) Econometric analysis of birth rate dynamics in Britain. J Hum Resour 23(4):563–576

Francesconi M, van der Klaauw W (2007) The socioeconomic consequences of in-work benefit reform for British lone mothers. J Hum Resour 42(1):1–31

Fraser CD (2001) Income risk, the tax-benefit system and the demand for children. Economica 68(269):105–125

Gregg P, Harkness S (2003) Welfare reform and lone parents employment in the UK. CMPO working paper series 03/072, University of Bristol

Gregg P, Harkness S, Smith S (2009) Welfare reform and lone parents. Econ J 119(535):F38–F65

Hills J, Waldfogel J (2004) A ‘Third Way’ in welfare reform: what are the lessons for the US? J Policy Anal Manage 23(4):765–788

Hoynes H (1997) Does welfare play any role in female headship decisions? J Public Econ 65(1997):89–118

Laroque G, Salanie B (2005) Fertility and financial incentives in France. CESifo Econ Stud 50(3):423–450

Laroque G, Salanie B (2008) Does fertility respond to financial incentives? CESifo working paper 2339

Leigh A (2007) Earned income tax credits and labor supply: evidence from a British Natural Experiment. Natl Tax J 60(2):205–224

Levine PB (2002) The impact of social policy and economic activity throughout the fertility decision tree. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 9021

McKay S (2000) Low/moderate-income families in Britain: work, working families’ tax credit and childcare in 2000. Department for Work and Pensions research report 161, London

McKay S (2001) Working families’ tax credit in 2001. Department for Work and Pensions research report 205, London

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Moffitt R (1998) The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In: Moffitt R (ed) Welfare, the family and reproductive behaviour: research perspectives. National Academy, Washington, pp 50–97

Moulton B (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72(2):334–338

Murphy M, Berrington A (1993) Constructing period parity progression ratios from household survey data. In: Bhrolchain MN (ed) New perspectives on fertility in Britain. HMSO, London pp 17–32

Whittington LA (1992) Taxes and the family: the impact of the tax exemption for dependents on marital fertility. Demography 29(2):215–226

Whittington LA, Alm J, Peters HE (1990) Fertility and the personal exemption: implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. Am Econ Rev 80(3):545–556

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the ESRC under its programme, Understanding Population Trends and Processes (RES-163-25-0018), and through the Centre for Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS. Material from the Family Expenditure Survey, the Family Resources Survey and the General Household Survey was made available by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) through the UK Data Archive and has been used by permission of the Controller of HMSO. The authors would like to thank Richard Blundell, Hilary Hoynes, Karl Scholz, Frank Windmeijer and an anonymous referee as well as seminar participants at CMPO, IFS, ONS and the Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Junsen Zhang

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brewer, M., Ratcliffe, A. & dSmith, S. Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. J Popul Econ 25, 245–266 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x