Abstract

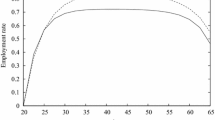

Given the empirical fact that workers of different ages are not perfect substitutes in production, this paper explores how change in the age pattern affects wages and (un)employment. We develop a general equilibrium model where wages for young and old workers are set by monopoly unions. Contrary to the common wisdom on this topic, we show that an increase in the relative number of older workers has no effect on young and old unemployment. If, however, unions attach a higher weight to the wishes of the old, the unemployment rate of the old (young) will increase (decrease). In this case, we observe a redistribution of wage income from the young to the old.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

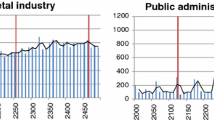

In the USA, the median age of the workforce is projected to rise from 35.4 years in 1986 to 42.1 years in 2016 (see Toossi 2007). In some countries, the ageing will be even stronger. According to the World Population Prospects of the United Nations (2007), western Europe will face an increase in the median age of the population from 34.5 in 1980 to 44.7 in 2020. In Germany, the modal age of the labour force is projected to rise from 36 years in 2000 to 54 years in 2020 (Börsch-Supan 2003).

Concerning the transition from junior to senior jobs, there seems to be a flaw in the Pissarides (1989) model. He assumes that, in each period, a fraction of old workers is separated from their senior job for exogenous reasons. Some of them, or even all, will get a junior job. In subsequent periods, they stay with the junior job, and they do not have a chance to switch back to a senior job. As a consequence, the number of old workers with a senior job constantly declines and goes to zero, which cannot be an equilibrium.

A simple alternative to our specification would be to assume that young and old workers are perfect substitutes in junior jobs. The modelling of such a scenario calls for some adjustments. First, the wages are identical, \(w_{1}^{y}=w_{1}^{0}\). Second, the labour demand functions 3 and 4 collapse to a single labour demand schedule for junior jobs. Third, there is a flow equilibrium for junior jobs which turns out to be \(z(N_{1}^{y}+N_{1}^{o})=h(L_{1}-N_{1}^{y}+(1-a)(L_{2}-N_{2}-N_{1}^{o}))\). And fourth, the optimal choice between young and old workers with junior jobs is now given by the requirement that, in a steady state, the ratio between separated jobs and job-seekers has to be the same for young and old workers: \(\frac{zN_{1}^{y}}{L_{1}-N_{1}^{y}}=\frac{zN_{1}^{o}}{ (1-a)(L_{2}-N_{2}-N_{1}^{o})}\). With these modifications at hand, we can solve the model. The derivation is somewhat cumbersome, and the results do not change very much compared to the results presented below. However, in order to sign the effects, it is sometimes necessary to put some restrictions on the initial steady state around which we log-linearize. Since these restrictions are not very intuitive, we drop the presentation of the solution of this scenario.

We impose the condition of ex ante neutrality where the policy is budget neutral at the initial steady state. The concept of ex post neutrality, where the budget is assumed to be neutral after all adjustments in the economy have taken place, is explored in Michaelis and Pflüger (2000) and Lingens (2004).

References

Aubert P, Caroli E, Roger M (2006) New technologies, organisation and age: firm-level evidence. Econ J 116(2):F73–F93

Barth MC, McNaught W, Rizzi P (1993) Corporations and the aging workforce. In: Mirvis PH (ed) Building the competitive workforce: investing in human capital for corporate success. Wiley, New York, pp 156–200

Blanchflower D (2007) International patterns of union membership. Br J Ind Relat 45(1):1–28

Börsch-Supan A (2003) Labor market effects of population aging. Labour 17(Special Issue):5–44

Hetze P, Ochsen C (2006) Age effects on equilibrium unemployment. Rostock Center for the Study of Demographic Change, Discussion Paper No. 1, Rostock

Ichino A, Schwert G, Winter-Ebmer R, Zweimüller J (2007) Too old to work, too young to retire? CEPR Discussion Paper No. 6510

Layard R, Nickell S (1990) Is unemployment lower if unions bargain over employment? Q J Econ 105(3):773–787

Layard R, Nickell S, Jackman R (2005) Unemployment—macroeconomic performance and the labour market, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lindbeck A (1993) Unemployment and macroeconomics. MIT, Cambridge

Lingens J (2004) Union wage bargaining and economic growth. Springer, Berlin

Michaelis J, Pflüger MP (2000) The impact of tax reforms on unemployment in a SMOPEC. J Econ 72(2):175–201

Pissarides CA (1989) Unemployment consequences of an aging population: an application of insider-outsider theory. Eur Econ Rev 33(2–3):355–366

Schmidt C (1993) Aging and unemployment. In: Johnson P, Zimmermann KF (eds) Labor markets in an aging Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 216–252

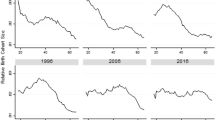

Schnabel C, Wagner J (2008a) Union membership and age: the inverted U-shape hypothesis under test. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3842

Schnabel C, Wagner J (2008b) The aging of the unions in west Germany, 1980–2006. Jahrb Natlökon Stat 228(5–6):497–511

Skirbekk V (2004) Age and individual productivity: a literature survey. In: Feichtinger G (ed) Vienna yearbook of population research. Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, pp 133–153

Toossi M (2007) Labor force projections to 2016: more workers in their golden years. Mon Labor Rev 130(11):33–52

United Nations (2007) World populations prospects: the 2006 revision. United Nations, New York

Zimmermann KF (1991) Ageing and the labor market—age structure, cohort size and unemployment. J Popul Econ 4(3):177–200

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments on earlier drafts of this paper to participants of research seminars at the universities of Gießen, Hamburg, Kassel, Marburg and Würzburg. Particular thanks go to Max Albert, Michael Bräuninger, Oliver Lorz, Michael Pflüger, Marco de Pinto and a referee of this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Michaelis, J., Debus, M. Wage and (un-)employment effects of an ageing workforce. J Popul Econ 24, 1493–1511 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0325-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0325-9