Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) has been reported in up to 25% of critically-ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in those with underlying comorbidities. AKI is associated with high mortality rates in this setting, especially when renal replacement therapy is required. Several studies have highlighted changes in urinary sediment, including proteinuria and hematuria, and evidence of urinary SARS-CoV-2 excretion, suggesting the presence of a renal reservoir for the virus. The pathophysiology of COVID-19 associated AKI could be related to unspecific mechanisms but also to COVID-specific mechanisms such as direct cellular injury resulting from viral entry through the receptor (ACE2) which is highly expressed in the kidney, an imbalanced renin–angotensin–aldosteron system, pro-inflammatory cytokines elicited by the viral infection and thrombotic events. Non-specific mechanisms include haemodynamic alterations, right heart failure, high levels of PEEP in patients requiring mechanical ventilation, hypovolemia, administration of nephrotoxic drugs and nosocomial sepsis. To date, there is no specific treatment for COVID-19 induced AKI. A number of investigational agents are being explored for antiviral/immunomodulatory treatment of COVID-19 and their impact on AKI is still unknown. Indications, timing and modalities of renal replacement therapy currently rely on non-specific data focusing on patients with sepsis. Further studies focusing on AKI in COVID-19 patients are urgently warranted in order to predict the risk of AKI, to identify the exact mechanisms of renal injury and to suggest targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Acute kidney injury (AKI) during SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with high mortality rates in ICU. The pathophysiology of AKI currently relies on unspecific mechanisms (hypovolemia, nephrotoxic drugs, high PEEP, right heart failure), a direct viral injury, an imbalanced Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) activation, an elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines elicited by the viral infection, and a procoagulant state. To date, there is no specific treatment for COVID-19 induced AKI. |

Introduction

Since December 2019, a novel coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) has caused an international outbreak of respiratory illness described as COVID-19. On the May 26, 2020, 5,404,512 confirmed cases of COVID-19 including 343,514 deaths were reported by The World Health Organization. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a frequent condition in critically ill patients, in particular in those with serious infections, and has been associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [1]. Since the onset of the new SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, several studies have focused on pulmonary complications, namely acute respiratory syndrome, which is the leading condition in intensive care unit (ICU) admission and associated with high mortality rate [2,3,4,5]. Initially little attention was paid to the AKI incidence in those patients, and kidney involvement was considered negligible [6]. However, there is growing evidence that AKI is prevalent in COVID-19 patients and that SARS-CoV-2 specifically invades the kidneys.

Epidemiology

In a case series of 116 non-critically ill Chinese patients from Wuhan, Wang L. et al. have found that only 12 (10.8%) experienced a small increase in serum creatinine or urea nitrogen within the first 48 h of hospital stay [6]. However, this has been challenged by most recent findings. As shown in Table S1, AKI during hospital stay is reported with an average incidence of 11% (8–17%) overall, with highest ranges in the critically ill (23% (14–35%)) (Table S1, Figs. 1 and 2). Of note, renal replacement therapy (RRT) was used in near 5% of the critically ill patients. These results have to be interpreted with caution. Indeed, the actual AKI incidence, in particular in ICU, remains uncertain and may have been underestimated due to the retrospective design of the studies and the lack of clear operational AKI definitions in most of the reports (Table S1). Of note, although several studies have used the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition [4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], none of them have reported AKI stages. In our center, in a cohort of 99 critically ill patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, 42 patients (42.9%) have developed AKI and among them 32 (74.4%) severe AKI (KDIGO stage III). RRT has been required in 13 patients (13.4%) (unpublished data). These discrepancies across studies could be explained by other factors such as race, patient characteristics (comorbidity, smoking), illness severity (inclusion of all clinical cases versus only laboratory-confirmed cases) and variation in local practice regarding fluid and hemodynamic management, ventilation strategy and medication use. These epidemiological findings should also be put into perspective with previous reports in other pandemic processes, such as H1N1 influenza, where similar incidences have been described.

AKI incidence in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection. Forestplot showing incidence of AKI in patients with COVID-19 infection. The square indicates the proportion of patients in each study. The vertical dashed line indicates the population mean (all datasets combined) and the blue diamond the 95% CI around that mean

AKI incidence in ICU in patients with COVID-19 infection. Forestplot showing incidence of AKI in critically ill patients with COVID 19 infection. The square indicates the proportion of patients in each study. The vertical dashed line indicates the population mean (all datasets combined) and the blue diamond the 95% CI around that mean

The timeline of AKI onset is another issue. Only four studies reported AKI at hospital admission [5, 10, 11, 14], with an incidence ranging from 1% [5] to 29% [11] (Table S1). In most studies, AKI developed throughout hospital stay, with an average of 5 to 9 days after admission [11, 15, 16]. AKI developed more frequently in patients with the most severe disease (in particular severe ARDS, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation), the older or those with comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes [8, 17]. As shown in Table S1, these conditions are frequently encountered in patients admitted for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

AKI is a well-recognized factor of poor prognosis [18]. In SARS-CoV-2 infection, five studies have found a significant association between kidney failure and death [8, 9, 11, 17, 19]. Interestingly, Cheng et al. [9] have found that only AKI stage 2 or higher was associated with a greater risk of mortality [HR: 3.53 (1.5–8.27)].

Urinalysis during SARS-CoV-2 infection

In parallel to kidney dysfunction defined by an increased in serum creatinine, several studies have highlighted abnormalities in the urinary sediment.

Proteinuria and hematuria

Proteinuria has been commonly observed during SARS-CoV-2 infection and is reported in 7 up to 63% of cases [6, 9, 20, 21]. Cheng et al. reported hematuria in 26.7% of the patients [9]. Two phenotypes of proteinuria have been identified: Most of the time proteinuria is of low abundance, rated at 1 + on the urinary dipstick, probably reflecting tubular injury. In some cases, proteinuria is abundant or constituted with albumin suggesting glomerular impairment. Viral injury to podocytes but also RAAS activation may have contributed to proteinuria: Accumulation of angiotensin II may be responsible for nephrin endocytosis and subsequently increased glomerular permeability with proteinuria [22]. Two cases of massive proteinuria associated with severe AKI and histological collapsing glomerulopathy were reported in 2 black patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 infection [23, 24]. This form of glomerulopathy has been linked to a variety of conditions, including viral infections [25]. Interestingly, both proteinuria and hematuria are strongly associated with an increased hospital mortality [9].

These results should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, proteinuria was measured at admission without previous values available. Yet, patients included in these studies often exhibited risk factors for kidney impairment such as diabetes, high blood pressure and overweight. Secondly, the association with mortality may reflect the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection but may also point to an advanced underlying patient condition. Third, especially in black patients, it cannot be excluded that the genetic APOL1 variant may have contributed to the pathogenesis of collapsing glomerulopathy. Finally, proteinuria and hematuria should be interpreted with caution in critically ill, febrile and oliguric patients, especially when determined by dipstick [26].

Increased kaliuresis

In a cohort of 175 patients infected with COVID-19, hypokalemia with increased kaliuresis, as a marker of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) activation, was associated with the most severe forms of SARS-CoV-2 infections requiring ICU admission. Indeed, 93% of patients hospitalized in ICU had hypokalemia at admission [27]. The authors suggest that increased kaliuresis is related to increased angiotensin II levels. However, data with specific measurements of all components of RAAS will be needed to confirm this hypothesis. Indeed, hypokalemia may be secondary to SARS-CoV-2-induced diarrhea, the use of diuretics or other drug-induced tubulopathies.

Presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the urine

Presence of SARS-CoV-2 has rarely been shown in the urine swabs of COVID-19 patients raising the possibility of a renal reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 (5,6,29). However, whether the presence of viral RNA in the urine swabs implies that the urine is contagious should be determined by testing for living virus.

Histopathological findings during acute kidney injury

Diao et al. first reported the postmortem analysis of kidney tissues of 6 patients who died from COVID-19 [28]. More recently, Su et al. have analyzed kidney histopathological lesions in 26 patients who died from COVID-19 [29]. Using light microscopy, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, they reported several abnormalities, including:

-

1.

Histopathological findings related to the underlying conditions of patients at risk for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases), such as nodular mesangial expanding and hyalinosis of arterioles in diabetic patients, arteriolosclerosis with ischemic glomeruli in patients with hypertension and/or cardiovascular diseases.

-

2.

Evidence of direct renal parenchyma infection: By light microscopy, Su et al. found diffuse acute proximal tubular injury with cytoplasmic vacuoles that may be related to direct viral infection in the proximal tubular epithelium. By transmission electron microscopy, virus particles were mainly identified in the cytoplasm of renal proximal tubular epithelium and in the podocytes, with secondary foot process effacement and detachment of podocytes from the glomerular basement membrane. By indirect fluorescence, tubular epithelium expressed SARS-CoV nucleoprotein in 3 patients [29]. Kissling et al. reported a case of severe collapsing focal glomerulopathy with in the podocyte cytoplasm, vacuoles containing numerous spherical particles that had the typical appearance of viral inclusion bodies [23]. Puelles et al. also detected a positive SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the autopsy of kidneys from COVID-19 patients, with preferential localization in glomeruli. Interestingly, multiple underlying conditions were associated with SARS-CoV-2 kidney tropism [30]. Thus, these studies suggest direct invasion of SARS-CoV-2 into renal parenchyma.

-

3.

Another common morphologic finding was diffuse erythrocyte aggregation and obstruction in the lumen of glomerular and peritubular capillaries without platelets, red blood cell fragments, fibrin thrombi or fibrinoid necrosis.

-

4.

Glomerular ischemia and endothelial cell injury were also present in some cases. Su et al. found evidence of glomerular ischemia in 3 patients with fibrin thrombi within the glomerular capillary loops [29], likely reflecting coagulation activation in COVID-19 patients [16].

-

5.

Other histological findings include myoglobin casts or cellular debris casts. Rhabdomyolysis has also been reported in patients with COVID-19 [31].

-

6.

Although lung injury during severe SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be partially linked to complement activation [32], there is no evidence of complement activation in the kidney [33].

It is important to keep in mind that most of histological data stem from postmortem analysis. It is therefore difficult to conclude whether these histological lesions are direct consequences of the virus or of sepsis and/or multiple organ failure [34]. More kidney biopsies of COVID-19 alive patients may help to answer this question.

Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury

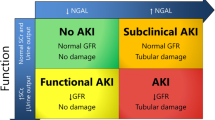

The pathophysiological understanding of COVID-19-related AKI is yet to be elucidated. Current knowledge suggests unspecific mechanisms, but also more COVID-19 specific mechanisms such as a direct viral injury via its receptor (ACE2) which is highly expressed in the kidney, an imbalanced RAAS, an elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines elicited by the viral infection and microvascular thrombosis (Fig. 3).

Mechanisms of acute kidney injury (AKI) during severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 can penetrate proximal tubule cells by linking with ACE2 and CD147, as well as in the podocytes, by linking with ACE2. Virus entry may be responsible for podocyte dysfunction, leading to glomerular diseases such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and acute proximal tubular injury leading to tubular necrosis. SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for an imbalanced RAAS activation that promotes glomerular dysfunction, fibrosis, vasoconstriction and inflammation. SARS-CoV-2 infection also triggers coagulation activation, leading to kidney vascular injury such as ischemic glomeruli and fibrinoid necrosis. Glomerular capillaries obstruction by red blood cells has also been reported during SARS-CoV-2 infection. The elevation of cytokines induced by severe SARS-CoV-2 infection may also participate to the genesis of AKI. Finally, unspecific factors relative to intensive care unit (ICU) management may aggravate kidney injury. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6, interleukine 6; IL-1β, interleukin 1; MCP1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ICU, intensive care unit

Unspecific mechanisms

Several factors may contribute to AKI onset, in particular in the critically ill [35]. First, most COVID-19 patients with AKI are older and have frequent comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus (Table S1) [2, 5, 7]. These factors are well-known factors of renal vulnerability. Recently, they have been identified as contributors to AKI development in patients with acute respiratory failure [36]. Moreover, due to these conditions, patients are frequently treated with drugs that interfere with regulation of renal flow, such as ACE inhibitors. This could be of importance, because a lot of patients experienced prolonged fever, tachypnea and gastro-intestinal troubles, which could lead to hypovolemia and subsequent pre-renal AKI [5, 7]. However, to date, no study reported specific data on volume status at the time of hospital admission and we can only assume the role of these factors in AKI onset [37]. Nephrotoxicity may also be involved. Radiographic contrast media used to investigate thromboembolic events (pulmonary embolism in particular) may play a role in AKI onset. Nephrotoxic drugs can also be incriminated in AKI development, especially antibiotics, antiviral therapy or traditional medicine. However, these factors have been poorly investigated in COVID-19 patients.

Second, others mechanisms could contribute to AKI development in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is the leading cause of admission in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [2, 5, 7]. Impairment of gas exchange and severe hypoxemia has been recognized as factors associated with AKI in patients with ARDS [38]. In a case series of 1591 patients admitted in ICU during the early stage of the outbreak in Lombardy, Grasselli et al. reported that severe hypoxemia (with a median PaO2/FiO2 at 160 [114–220] mmHg at ICU admission) is common. Hemodynamic disturbances such as central venous pressure elevation, increased intra-thoracic pressure or volume overload may also result in AKI initiation or aggravation [39]. Although there is a low level of clinical evidence [40], several physiological studies suggested that high intra-thoracic pressures and PEEP could influence urine output and glomerular filtration [41, 42].

Recently, Gattinoni et al. have argued that, in the early phase of COVID‑19 pneumonia, pulmonary mechanics may be different from traditional ARDS, with a phenotype (called Type-L in contrast to Type-H with more classical aspects) characterized by normal compliance, low lung recruitability and without need for very high PEEP or even deleterious effects of the latter [43]. In other words, high and kidney-unfriendly levels of PEEP may not be required in the early phase of COVID-19 ARDS. Finally, inflammatory effects of invasive mechanical ventilation per se especially when a non-protective strategy is applied [44] could also contribute to kidney injury [45].

Entry of SARS-CoV-2 cells into the kidney

Angiotensin conversion enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a homolog of ACE that converts angiotensin II to angiotensin 1–7, which alleviates renin–angiotensin system-related vasoconstriction (Fig. 4). There are 2 forms of ACE2: soluble ACE2 and membrane-bound ACE2. SARS-CoV-2 binds with ACE2 on the cell membrane of the host cells. Cell entry of coronavirus depends on binding of the viral spike (S) proteins to cellular receptors and on S protein priming by host cell proteases. Therefore, cell invasion depends on ACE2 expression and also the presence of the protease TMPRSS2 (Transmembrane protease, serine 2), that is able to cleave the viral spike [46]. In the kidneys, ACE2 is expressed in the apical brush borders of the proximal tubules as well as the podocytes. In endothelial cells of the kidney, only ACE is expressed without detectable ACE2 [47]. Recent human tissue RNA-sequencing data demonstrated that kidney expression of ACE2 was nearly 100-fold higher than in pulmonary tissue [20]. TMPRSS2 has also been detected in the kidney [48] and more specifically in the proximal tubules [49]. More recently, Wang et al. found that SARS-CoV-2 invaded host cells via a novel route of CD147-spike protein [50]. CD147 is ubiquitously expressed transmembrane glycoprotein and is highly expressed on proximal tubular epithelial cells and inflammatory cells and has been involved in various kidney diseases [51].

Role of ACE2 and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Angiotensinogen is converted into angiotensin I by renin and then into angiotensin II (also known as angiotensin (1–8)) by ACE. Angiotensin II, through its binding to AT1R, is responsible for the deleterious effects of RAAS activation (i.e., fibrosis, inflammation, vasoconstriction). ACE2 counteracts deleterious effects of RAAS activation by converting angiotensin I into angiotensin (1–9) and angiotensin II into angiotensin 1–7 that binds to Mas receptor and exerts anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory effects. SARS-CoV-2 binds to membrane-bound ACE2 and invades the cell membrane by endocytosis thus reducing levels of membrane-bound ACE2. Cell invasion depends on ACE2 expression and also on the presence of the protease TMPRSS2, that is able to cleave the viral spike. Diminution of ACE2 results in an accumulation of angiotensin II that is responsible for overactivation of RAAS, leading to increased inflammation, fibrosis, vasoconstriction. Circulating ACE2 could act as a decoy and bind to SARS-CoV-2, thereby preventing internalization of membrane-bound ACE2 by SARS-CoV-2. Under physiological conditions, ACE2 is linked to AT1R, forming a complex that prevents degradation of membrane-bound ACE2 through lysozome internalization. Angiotensin II links to AT1R and decreases the interaction between ACE2 and AT1R, inducing ubiquitination and internalization of ACE2. ARB may increase membrane-bound ACE2 availability by preventing its internalization. However, as the virus requires membrane-bound ACE2 internalization to penetrate the cell, ARB may also decrease the susceptibility to the virus by preventing from virus-ACE2 internalization. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ATII, angiotensin II; AT1R, angiotensin receptor type I; ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Mas-R, Mas receptor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease, serine 2

Imbalanced RAAS activation

First, the SARS-CoV-2 attaches to ACE2 and induces a down-regulation of membrane-bound ACE2 that promotes accumulation of angiotensin II by reducing its degradation into angiotensin 1–7. Thus, COVID-19 mediated angiotensin II accumulation may promote an imbalanced RAAS activation, leading to inflammation, fibrosis, vasoconstriction [52] (Fig. 4).

Secondly, ACE2 usually interacts with AT1 receptor, forming a complex that prevents internalization and degradation of membrane-bound ACE2 into lysosomes. Accumulation of angiotensin II decreases this interaction and induces ubiquitination and internalization of membrane-bound ACE2 into lysosomes [53] (Fig. 4).

Role of RAAS inhibitors

Because of the RAAS activation and the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2, some authors have suggested RAAS inhibitors as potential treatments for COVID-19 infection [54]. Conversely, other studies have suggested that ACE inhibitors and ARB may increase ACE2 expression and therefore increase the susceptibility of patients to SARS-CoV-2 infection [55, 56]. However, membrane-bound and circulating ACE2 may exert antagonist effects on COVID-19 invasiveness. Circulating ACE2 may act as a decoy by preventing SARS-CoV-2 entry into target cells which depends on its membrane-bound ACE2 receptor. This means that besides the ACE/ACE2 balance, the soluble ACE2/membrane-bound ACE2 balance is equally as important. The role of RAAS inhibitors should be then examined in light of its potential disruption of both of these equilibriums [52]. Two recent retrospective studies have suggested that RAAS inhibitors could be protective in COVID-19 patients [57, 58]. In the first retrospective study including 1128 patients with hypertension, the authors observed a decreased risk of all-cause mortality in patients receiving ACE inhibitors/ARB [57]. In the second study, a small retrospective cohort, RAAS inhibitor use was associated with a tendency to a lower proportion of critical patients and lower mortality rate [58].

Recent clinical studies suggest the lack of association between RAAS inhibitors and the risk of COVID-19 or mortality [59,60,61]. To date, cardiovascular societies have therefore recommended against adding or stopping RAAS inhibitors.

Role of cytokines in COVID-associated AKI

There is accumulating evidence that severe COVID-19 patients have elevated level of inflammatory cytokines, especially when they are admitted to the ICU. Huang et al. showed that interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-1RA, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-γ (IFNγ), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), interferon-γ-inducible protein (IP10), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP1A), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were increased, among which IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, G-CSF,IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, TNFα were higher in critically ill patients [7]. These cytokines may participate to AKI in COVID-19 patients, by interacting with kidney resident cells and inducing endothelial and tubular dysfunction. For example, TNF-α can bind directly to tubular cell receptors, triggering the death receptor pathway of apoptosis [62]. Other studies have also found an elevation of IL-6 in critically ill patients with COVID-19 with increased IL-6 levels in non-survival group of COVID-19 patients when compared to survivors [16]. The deleterious role of IL-6 has been demonstrated in different models of AKI, including ischemic AKI, nephrotoxin-induced AKI and sepsis-induced AKI [63, 64]. In a model of nephrotoxin-induced AKI, TNFα−/− mice and IL-6−/− mice display relative resistance to AKI [64]. IL-6 also induces an increased renal vascular permeability, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokines by renal endothelial cells (IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1), and may participate to microcirculatory dysfunction [65]. Therefore, we can assume that these cytokines may participate to AKI in COVID-19 patients. However, elevation of cytokines is moderate (median IL-6 of 79 pg/ml (39–135 pg/ml) in our ICU cohort (unpublished data)) when compared to hyper-inflammatory ARDS (median IL-6 of 1568 pg/mL; 517-3205 pg/mL) [66], sepsis (median IL-6 of 1346 pg/mL; 292-8789 pg/mL) [67] or cytokine release syndrome where median interleukin-6 may approach 10000 pg/mL [68]. Moreover, whether the elevation of cytokines in COVID-19 patients translates into a beneficial effect of immunomodulatory strategies is still unknown.

Role of thrombosis in COVID-associated AKI

The high incidence of acute thrombotic events in COVID-19 patients has been reported by several authors, mainly venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [69, 70]. Helms et al. found that 16.7% of critically ill patients admitted for SARS-CoV-2 infection had pulmonary embolism. Interestingly, COVID-19 ARDS patients exhibited more thrombotic complications than non-COVID-19 ARDS patients [70]. In the kidney, the presence of fibrin deposits in glomerular loops [29] is in favor of a dysregulation of coagulation homeostasis that can participate to renal microcirculatory dysfunction and AKI. In a retrospective study, Tang et al. demonstrated that the use of prophylactic anticoagulant therapy was associated with decreased mortality in COVID-19 patients [71]. However, no data are available on the impact of anticoagulant therapy on renal outcomes. High prevalence of pulmonary embolism during SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent right heart failure may also contribute to venous congestion and development of AKI [72].

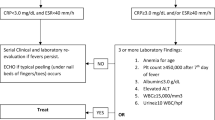

Treatment of COVID-19-induced AKI

To date, there is no specific treatment for COVID-19-induced AKI. A number of investigational agents are being explored for treatment of COVID-19 [73]. However, there are no controlled data supporting the use of any specific treatment (antiviral drugs or immunomodulatory drugs), and their efficacy for COVID-19 is still unknown. Concerning RRT, there are no data supporting the use of different strategies than those used in the context of sepsis. The timing of RRT, modality (intermittent versus continuous) and dose may therefore rely on non-COVID-19 data [74]. Of note, Helms et al. found a high incidence of filter clotting during RRT (especially during continuous veno-venous hemofiltration, with up to 96.6% of filter clotting) [70]. If possible, citrate regional anticoagulation (in addition to systemic anticoagulation) should then be preferred. If not, special attention should be paid to administer efficient heparin anticoagulation.

To date, there is no evidence for clinically important cytokine removal with RRT during sepsis-induced AKI and no data are available in the setting of COVID-19 [75].

In case of persistent proteinuria or hematuria at ICU discharge, COVID-19 patients may benefit from follow-up by a nephrologist.

Conclusion

AKI is prevalent in critically ill COVID-19 patient. Kidney involvement is associated with poor outcomes. Several mechanisms are possibly involved in kidney injury during SARS-CoV-2 infection, including direct invasion of SARS-CoV-2 into the renal parenchyma, an imbalanced RAAS and microthrombosis but also kidney injury secondary to hemodynamic instability, inflammatory cytokines and the consequences of therapeutics that are used in ICU (nephrotoxic drugs, mechanical ventilation). Early detection and specific therapy of renal changes, including adequate hemodynamic support and avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs, may help to improve critically ill patients with COVID-19.

References

Peerapornratana S, Manrique-Caballero CL, Gómez H, Kellum JA (2019) Acute kidney injury from sepsis: current concepts, epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Kidney Int 96:1083–1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.026

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A et al (2020) Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394

Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M et al (2020) Covid-19 in critically Ill patients in the seattle region–case series. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2004500

Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L et al (2020) Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically Ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4326

Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Wang L, Li X, Chen H et al (2020) Coronavirus disease 19 infection does not result in acute kidney injury: an analysis of 116 hospitalized patients from Wuhan, China. AJN. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507471

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Wen C, Yali Q, Zirui G et al (2020) Prevalence of acute kidney injury in severe and critical COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K et al (2020) Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005

Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P et al (2020) Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan: a retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC

Li Z, Wu M, Yao J et al (2020) Kidney dysfunctions of COVID-19 patients: a multi-centered, retrospective, observational study. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Chen T, Wu D, Chen H et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 368:m1091. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1091

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323:1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

Xu S, Fu L, Fei J, et al (2020) Acute kidney injury at early stage as a negative prognostic indicator of patients with COVID-19: a hospital-based retrospective analysis. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.24.20042408

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J et al (2020) Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

Xu S, Fu L, Fei J et al (2020) Acute kidney injury at early stage as a negative prognostic indicator of patients with COVID-19: a hospital-based retrospective analysis. medRxiv 2020.03.24.20042408. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.24.20042408

Murugan R, Kellum JA (2011) Acute kidney injury: what’s the prognosis? Nat Rev Nephrol 7:209–217. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2011.13

Chen R, Liang W, Jiang M et al (2020) Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.010

Anti-2019-nCoV Volunteers, Li Z, Wu M et al (2020) Caution on kidney dysfunctions of 2019-nCoV patients. medRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.08.20021212

Cao M, Zhang D, Wang Y et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in Shanghai, China. medRxiv 2020.03.04.20030395. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.04.20030395

Martínez-Rojas MA, Vega-Vega O, Bobadilla NA (2020) Is the kidney a target of SARS-CoV-2? American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology ajprenal.00160.2020. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2020

Kissling S, Rotman S, Gerber C et al (2020) Collapsing glomerulopathy in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.006

Larsen CP, Bourne TD, Wilson JD et al (2020) Collapsing glomerulopathy in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Kidney Int Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.002

Nasr SH, Kopp JB (2020) COVID-19–associated collapsing glomerulopathy: an emerging entity. Kidney Int Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.030

Nguyen MT, Maynard SE, Kimmel PL (2009) Misapplications of commonly used kidney equations: renal physiology in practice. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4:528–534. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05731108

Chen D, Li X, Song Q et al (2020) Hypokalemia and clinical implications in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). medRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.27.20028530

Diao B, Wang C, Wang R et al (2020) Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. medRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.04.20031120

Su H, Yang M, Wan C et al (2020) Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003

Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT et al (2020) Multiorgan and Renal Tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2011400

Jin M, Tong Q Early Release - Rhabdomyolysis as Potential Late Complication Associated with COVID-19 - Volume 26, Number 7—July 2020 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200445

Risitano AM, Mastellos DC, Huber-Lang M et al (2020) Complement as a target in COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-0320-7

McCullough JW, Renner B, Thurman JM (2013) The role of the complement system in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.08.005

Lerolle N, Nochy D, Guérot E et al (2010) Histopathology of septic shock induced acute kidney injury: apoptosis and leukocytic infiltration. Intensiv Care Med 36:471–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-009-1723-x

Acute kidney injury in the ICU: from injury to recovery: reports from the 5th Paris International Conference. - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28474317. Accessed 23 Apr 2020

Panitchote A, Mehkri O, Hastings A et al (2019) Factors associated with acute kidney injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensiv Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0552-5

Hendren NS, Drazner MH, Bozkurt B, Cooper LT (2020) Description and proposed management of the acute COVID-19 cardiovascular syndrome. Circulation. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047349

Darmon M, Schortgen F, Leon R et al (2009) Impact of mild hypoxemia on renal function and renal resistive index during mechanical ventilation. Intensiv Care Med 35:1031–1038. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-008-1372-5

Joannidis M, Forni LG, Klein SJ et al (2020) Lung-kidney interactions in critically ill patients: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 21 Workgroup. Intensiv Care Med 46:654–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05869-7

van den Akker JPC, Egal M, Groeneveld ABJ (2013) Invasive mechanical ventilation as a risk factor for acute kidney injury in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 17:R98. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12743

Husain-Syed F, Slutsky AS, Ronco C (2016) Lung-kidney cross-talk in the critically Ill patient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194:402–414. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201602-0420CP

Annat G, Viale JP, Bui Xuan B et al (1983) Effect of PEEP ventilation on renal function, plasma renin, aldosterone, neurophysins and urinary ADH, and prostaglandins. Anesthesiology 58:136–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-198302000-00006

Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P et al (2020) COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensiv Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2

Injurious Mechanical Ventilation and End-Organ Epithelial Cell Apoptosis and Organ Dysfunction in an Experimental Model of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome | Critical Care Medicine | JAMA | JAMA Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/196447. Accessed 23 Apr 2020

Ranieri VM, Giunta F, Suter PM, Slutsky AS (2000) Mechanical ventilation as a mediator of multisystem organ failure in acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 284:43–44. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.1.43

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

Mizuiri S, Ohashi Y (2015) ACE and ACE2 in kidney disease. World J Nephrol 4:74–82. https://doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v4.i1.74

Ransick A, Lindström NO, Liu J et al (2019) Single-cell profiling reveals sex, lineage, and regional diversity in the mouse kidney. Dev Cell 51:399–413.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.005

Pan X, Xu D, Zhang H et al (2020) Identification of a potential mechanism of acute kidney injury during the COVID-19 outbreak: a study based on single-cell transcriptome analysis. Intensiv Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06026-1

Wang K, Chen W, Zhou Y-S et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells via a novel route: CD147-spike protein. bioRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.14.988345

Chiu P-F, Su S-L, Tsai C-C et al (2018) Cyclophilin A and CD147 associate with progression of diabetic nephropathy. Free Radic Res 52:1456–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2018.1523545

Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T et al (2020) Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:1653–1659. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr2005760

Deshotels MR, Xia H, Sriramula S et al (2014) Angiotensin II mediates angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 internalization and degradation through an angiotensin II type I receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension 64:1368–1375. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03743

Losartan for Patients With COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04312009. Accessed 27 Apr 2020

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC et al (2005) Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 111:2605–2610. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461

Vuille-dit-Bille RN, Camargo SM, Emmenegger L et al (2015) Human intestine luminal ACE2 and amino acid transporter expression increased by ACE-inhibitors. Amino Acids 47:693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-014-1889-6

Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J et al (2020) Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res CIRCRESAHA. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134

Yang G, Tan Z, Zhou L et al (2020) Effects Of ARBs And ACEIs On Virus Infection, Inflammatory Status And Clinical Outcomes In COVID-19 Patients With Hypertension: A Single Center Retrospective Study. Hypertension .1:2. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15143

Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M et al (2020) Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2006923

Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C et al (2020) Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2008975

de Abajo FJ, Rodríguez-Martín S, Lerma V et al (2020) Use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. Lancet. 395(10238):1705–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8

Cunningham PN, Dyanov HM, Park P et al (2002) Acute renal failure in endotoxemia is caused by TNF acting directly on TNF receptor-1 in kidney. J Immunol 168:5817–5823. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5817

Su H, Lei C-T, Zhang C (2017) Interleukin-6 signaling pathway and its role in kidney disease: an update. Front Immunol 8:405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00405

Nechemia-Arbely Y, Barkan D, Pizov G et al (2008) IL-6/IL-6R axis plays a critical role in acute kidney injury. JASN 19:1106–1115. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007070744

Desai TR, Leeper NJ, Hynes KL, Gewertz BL (2002) Interleukin-6 causes endothelial barrier dysfunction via the protein kinase C pathway. J Surg Res 104:118–123. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsre.2002.6415

Sinha P, Delucchi KL, McAuley DF et al (2020) Development and validation of parsimonious algorithms to classify acute respiratory distress syndrome phenotypes: a secondary analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 8:247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30369-8

Opal SM, Laterre P-F, Francois B et al (2013) Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the access randomized trial. JAMA 309:1154. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.2194

Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA et al (2014) Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 371:1507–1517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1407222

Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM et al (2020) Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

CRICS TRIGGERSEP Group (Clinical Research in Intensive Care and Sepsis Trial Group for Global Evaluation and Research in Sepsis), Helms J, Tacquard C et al. (2020) High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensiv Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18:844–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14768

Chen C, Lee J, Johnson AE et al (2017) Right ventricular function, peripheral edema, and acute kidney injury in critical illness. Kidney Int Rep 2:1059–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2017.05.017

Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D et al (2020) Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007016

Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F et al (2016) Initiation strategies for renal-replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 375:122–133. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1603017

Ronco C, Reis T, De Rosa S (2020) Coronavirus epidemic and extracorporeal therapies in intensive care: si vis pacem para bellum. Blood Purif. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507039

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Pr Darmon received funding from Sanofi (travel), Gilead-Kite (consulting and speaker), Astellas (speaker), Astute Medical (research support) and MSD (research support and speaker). Pr Azoulay has received fees for lectures from MSD, Pfizer and Alexion; his institution and research group have received support from Baxter, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Fisher & Paykel, Gilead, Alexion and Ablynx; and he received support for article research from Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris. Pr. Zafrani’s institution received funding from the Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Jazz Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gabarre, P., Dumas, G., Dupont, T. et al. Acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 46, 1339–1348 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06153-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06153-9