Abstract

Objective

To provide a narrative review of the latest concepts and understanding of the pathophysiology of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI).

Participants

A multispecialty task force of international experts in critical care medicine and endocrinology and members of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM).

Data sources

Medline, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Results

Three major pathophysiologic events were considered to constitute CIRCI: dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, altered cortisol metabolism, and tissue resistance to glucocorticoids. The dysregulation of the HPA axis is complex, involving multidirectional crosstalk between the CRH/ACTH pathways, autonomic nervous system, vasopressinergic system, and immune system. Recent studies have demonstrated that plasma clearance of cortisol is markedly reduced during critical illness, explained by suppressed expression and activity of the primary cortisol-metabolizing enzymes in the liver and kidney. Despite the elevated cortisol levels during critical illness, tissue resistance to glucocorticoids is believed to occur due to insufficient glucocorticoid alpha-mediated anti-inflammatory activity.

Conclusions

Novel insights into the pathophysiology of CIRCI add to the limitations of the current diagnostic tools to identify at-risk patients and may also impact how corticosteroids are used in patients with CIRCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2008 an international multidisciplinary task force convened by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) coined the term "critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency" (CIRCI) to describe impairment of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during critical illness [1]. CIRCI was defined as inadequate cellular corticosteroid activity for the severity of the patient’s critical illness, manifested by insufficient glucocorticoid–glucocorticoid receptor-mediated downregulation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors. CIRCI is thought to occur in several acute conditions, including sepsis and septic shock, severe community-acquired pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiac arrest, head injury, trauma, burns, and post-major surgery. This narrative review, performed by a multispecialty task force of international experts and members of the SCCM and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), focuses on the latest concepts and understanding of the pathophysiology of CIRCI during critical illness.

Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis and the physiological response to stress

Systemic inflammation—a central component of the innate immune system—is a highly organized response to infectious and non-infectious threats to homeostasis that consists of at least three major domains: (1) the stress system mediated by the HPA axis and the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine/sympathetic nervous system, (2) the acute-phase reaction, and (3) the target (vital organs) tissue defense response [2, 3]. Whereas appropriately regulated inflammation—tailored to stimulus and time [4]—is beneficial, excessive or persistent systemic inflammation incites tissue destruction and disease progression [5].

Overwhelming systemic inflammation that characterizes critical illness is partly driven by an imbalance between hyperactivated inflammatory pathways such as the classical nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) signaling system [6] and the less activated or dysregulated HPA-axis response [7]. The activated glucocorticoid–glucocorticoid receptor-alpha (GC-GRα) complex plays a fundamental role in the maintenance of both resting and stress-related homeostasis and influences the physiologic adaptive reaction of the organism against stressors [2]. The activated GC-GRα complex exerts its activity at the cytoplasmic level and on nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid (nDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [8] affecting thousands of genes involved in response to stress and non-stress states [9]. Individual genetic variants of the glucocorticoid receptor may also affect both the basic cellular phenotypes, i.e., GR expression levels and the overall HPA axis stress response through either an altered GC response or sensitivity [10].

Cortisol synthesis

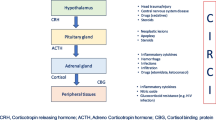

The adrenal glands produce glucocorticoids (cortisol), mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), and adrenal androgens (dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA) using cholesterol as a substrate and upon stimulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), also known as corticotropin (Fig. 1). ACTH is a short-half-life, fast-acting 39-amino acid peptide produced from the cleavage of a large precursor, pro-opiomelanocortin. ACTH stimulatory activity is regulated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and to a lesser extent by arginine vasopressin (AVP), both acting synergistically. Steroidogenic cholesterol is stored in lipid droplets as cholesteryl esters. Adrenal mitochondria play a critical role in adrenocortical cell steroidogenesis, converting intracellular cholesterol to cortisol. The final steps in glucocorticoid biosynthesis are catalyzed by two closely related mitochondrial P450-type enzymes: CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 [11]. Cortisol is the major endogenous glucocorticoid secreted by the human adrenal cortex. Cortisol is released in a circadian rhythm: cortisol production is at its peak in the early hours of the morning and then secretion gradually declines over the course of the day. Cortisol itself exerts inhibitory control on the pituitary and hypothalamus to regulate its release. The estimated daily production rate of cortisol is 27–37.5 µmol/day (5–7 mg/m2/day) [12]. There is limited adrenal storage of cortisol.

Glucocorticoid synthesis at rest and during stress. At rest, glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) are produced from the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex upon stimulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) released in the blood from the anterior pituitary gland. Both corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP), synthesized in the hypothalamus, contribute to the synthesis and release of ACTH by pituitary cells. During stress, the synthesis of ACTH is additionally stimulated by norepinephrine, mainly produced in the locus ceruleus. At the level of inflamed tissues, terminal nerve endings of afferent fibers of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) have receptors for damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) allowing them to sense the threat and activate the noradrenergic/CRH system. These DAMPs and PAMPs can also directly stimulate adrenal cortex cells that possess Toll-like receptors (TLR), resulting in ACTH-independent cortisol synthesis. In addition, paracrine routes allow the medulla to also stimulate glucocorticoid synthesis independently of ACTH

Under the stress of critical illness, the regulation of cortisol production becomes much more complex, involving multidirectional crosstalk between the CRH/ACTH pathways, autonomic nervous system, vasopressinergic system, and immune system (Fig. 1). Acute stress induces rapid release of ACTH via CRH and AVP and loss of the circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion. In critically ill patients, increased cortisol levels do not appear to be due to increased adrenocortical sensitivity to ACTH [13]. The dissociation of cortisol from ACTH could be due to direct production of cortisol from the adrenal glands or to reduced metabolism of cortisol and thus an increased systemic half-life. Cortisol production rates in critically ill patients were recently shown to be either unaltered or only slightly increased compared with matched control subjects tested in an intensive care unit (ICU) environment [14, 15].

Cortisol transport and metabolism

In plasma, a large proportion (80–90%) of circulating cortisol is bound with high affinity to corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG), with smaller (10–15%) proportions bound with low affinity to albumin or present in the ‘free’ unbound form. The binding capacity of CBG is typically saturated at cortisol concentrations of 22–25 µg/dl. When cortisol levels are higher than 25 µg/dl, there is an increased proportion of albumin-bound and free cortisol, whereas the amount of CBG-bound cortisol remains the same. Albumin and CBG are negative acute phase reactants and rapidly decrease in critical illness in proportion to the severity of illness [16]. In septic patients, reduction in CBG levels correlates with plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels [17].

Cortisol is metabolized primarily in the liver and the kidneys. In the liver the most important enzymes catalyzing the initial steps in cortisol metabolism are the 5 α/β-reductases, whereas in the kidney, cortisol is broken down to the inactive metabolite cortisone by the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD) type 2 enzyme [14]. Some cortisol can be regenerated from cortisone in extra-adrenal tissues (liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscles) through the activity of the 11β-HSD1 enzyme. The adverse metabolic complications associated with corticosteroid excess involve the key metabolic tissues (liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscles), which have comparatively high 11β-HSD1 activity.

In stressed conditions, the increase in cortisol level can lead to an increase in the free fraction in the circulation. Additionally, plasma CBG levels can decrease through reduced liver synthesis and increased peripheral cleavage by activated neutrophil elastases. These effects act to increase the amount of cortisol delivered to the tissues. During stress the metabolism of cortisol can also undergo significant changes. The expression and activity of 5-reductases within the liver and probably other tissues is decreased in response to inflammation [14]. Renal 11β-HSD2 is also decreased in response to inflammation, while the expression of 11β-HSD1 is increased in some tissues [18]. Up-regulation of 11β-HSD1 activity is modulated by inflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β]. These effects would be expected to increase the cortisol action at the level of specific tissues and also increase the half-life of circulating cortisol [18, 19].

Cellular cortisol signaling

Cortisol is a lipophilic hormone that enters cells passively and binds to specific cytoplasmic receptors, or to membrane sites. There are two types of glucocorticoid receptors (GR). The type 1 receptor is more commonly referred to as the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and the type 2 receptor as the classical GR. Both the GR and the MR can bind aldosterone and cortisol. In many tissues the ability of the MR to bind cortisol is reduced by the expression of the 11β-HSD2 enzyme and the conversion to inactive cortisone. The MR has a higher affinity for cortisol and aldosterone than the GR and is thought to be important for signaling at low corticosteroid concentrations. Although the MR is involved in some inflammatory responses, the classic GR is thought to be more important in mediating the glucocorticoid responses to stress and inflammation. Several transcriptional and translational isoforms of the GR exist, which appear to vary in their tissue distribution and gene-specific effects. Our current understanding of the GR's mechanism of action is mainly obtained from research on the almost ubiquitous and most abundant full-length GRα isoform [20].

In the absence of glucocorticoids, the GR is primarily present in the cytoplasm as part of a multiprotein complex with chaperone proteins, heat shock proteins, and immunophilins (FKBP51 and FKBP52). Upon binding of glucocorticoid, the GR undergoes a conformational change, dissociates from the chaperone proteins, and enters the nucleus and mitochondria, where it binds to positive (transactivation) or negative (cis-repression) specific DNA regions termed glucocorticoid responsive elements (GRE) to regulate transcription and translation of target genes in a cell- and gene-specific manner [21, 22] (Fig. 2). The glucocorticoid receptor can inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory genes independently of DNA binding by physically interacting (via tethering) with the transcription factor p65, a subunit of nuclear factor κB, an effect referred to as transrepression. This interaction inhibits p65–p50 heterodimer translocation into and action at the nucleus [21]. Alternatively, in transactivation, GR binding to GRE in the promoter regions of target genes is followed by recruitment of other proteins such as co-activators, resulting in increased pro-inflammatory gene transcription.

Glucocorticoid synthesis and signaling. Glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) are synthesized from cholesterol in the mitochondria by two P450-type enzymes, CYP11B1 and CYPB11B2, and may exert genomic and non-genomic effects. Glucocorticoids diffuse through cell membranes and bind with glucocorticoid receptors (GR, classic GR and MR, mineralocorticoid receptor). Glucocorticoid receptors reside in the cytoplasm in a multiprotein complex with chaperone proteins, heat shock proteins, and immunophilins. The classic GR (specifically GR-α) is the major receptor involved in mediating the glucocorticoid responses to stress and inflammation. Upon binding of cortisol, the GR undergoes a conformational change that allows it to dissociate from the chaperone proteins and translocate into the nucleus and the mitochondria, where it binds to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) to activate (transactivation) or repress (cis-repression) pro-inflammatory gene expression of various transcription factors (TFs) such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-KΒ) and activator protein-1 (AP-1)

Glucocorticoids can induce some anti-inflammatory effects through non-genomic effects (Fig. 2). Specifically, membrane-bound GR can activate kinase pathways within minutes. The activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway results in the inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A2α, whereas activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase leads to the induction of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS) and the subsequent production of nitric oxide [21]. Endothelial GR is a critical regulator of NO synthesis in sepsis [23]. In experimental lipopolysaccharide (LPS) models, tissue-specific deletion of the endothelial GR results in prolonged activation of NF-kB with increased expression of eNOS and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TNF-α, and IL-6 [23]. Importantly, the presence of endothelial GR is required for dexamethasone to rescue the animals from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced morbidity and mortality [24]. Glucocorticoids may also impair T cell receptor signaling through non-genomic inhibition of FYN oncogene-related kinase and lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase by the glucocorticoid receptor [21].

In addition to the wild-type glucocorticoid receptor GRα, two splice variants involving the hormone-binding domain exist, namely GRβ and GR-P (also known as GRδ) [25, 26]. GRβ differs from the GRα at the C terminus, resulting in a lack of binding to GCs, constitutive localization in the nucleus, and an inability to transactivate a GC-responsive reporter gene. However, it acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of GRα genomic transactivation and transrepression when co-expressed with GRα; imbalance between GR-α and GR-β expression is associated with GC insensitivity [26]. Cell-specific glucocorticoid responsiveness also involves differential expression of co-receptor proteins functioning as co-activators and co-repressors of transcription. Also, differences in chromatin structure and DNA methylation status of GR-target genes determine cell specific cortisol effects [27]. Besides classical genomic and rapid GC-induced non-genomic ligand-dependent steroid receptor actions and crosstalk, there is increasing evidence that the unliganded GR can modulate cell signaling in the absence of glucocorticoids, adding another level of complexity [20].

In sepsis, glucocorticoids may decrease HLA-DR expression on circulating monocytes at a transcriptional level via a decrease in the class II transactivator A transcription [28]. Another study found that hydrocortisone treatment reduced the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as soluble TNF receptors I and II and IL-10, and has only limited effects on HLA-DR expression by circulating monocytes [29].

Dysfunction of the HPA axis during critical illness

Many of the responses normally considered adaptive may be inadequate or counterproductive during severe stress states. Depending on the population of patients studied and the diagnostic criteria, dysfunction of the HPA axis has been estimated to occur at rates from 10 to 20% in critically ill medical patients to as high as 60% in patients with septic shock [1].

Evidence from the sepsis [30,31,32,33,34], ARDS [7, 35, 36], and trauma [37, 38] literature suggests that degree of elevation in inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF, IL-1β, IL-6) on ICU admission and during ICU stay correlates with disease severity and hospital mortality, and that persistent elevation of cytokines at hospital discharge is associated with adverse long-term outcomes [39].

Cytokine-induced activation of the HPA axis

Inflammatory cytokines including TNF, IL-1 and IL-6 have been shown to activate the HPA axis, especially during sepsis. However, these cytokines do not exert an equivalent effect on CRH release. IL-1 injection is associated with a strong and sustained activation of the HPA axis, while IL-6 and TNF induce weak and transient hypothalamic responses, and IL-2 and interferon-alpha have no effect [40]. The route of cytokine administration (intravenous or intraperitoneal) also influences their stimulatory effects on the hypothalamus [41].

It is also likely that cytokines can exert a direct, ACTH-independent effect on adrenal cortisol synthesis [42]. The presence of TNF and of its receptors within the adrenal glands suggests that this cytokine plays a role in adrenal function, even though experiments found variably stimulatory [43, 44] or inhibitory [45, 46] effects of TNF on steroidogenesis. Likewise, IL-1 and its receptor are also produced in the adrenal glands and contribute to steroidogenesis at least partly by regulating prostaglandin pathways [47]. Toll-like receptors (TLR), mainly TLR2 and TLR4, are expressed in the adrenal glands and play a critical role in the local immune-endocrine crosstalk in LPS-challenged rodents [48, 49]. Further experiments using genetically manipulated mice suggest that immune cells and not steroid-producing cells are key regulators of the immune-endocrine local interaction [49].

Impairment of adrenal cortisol synthesis

Damage to neuroendocrine cells

Sepsis is infrequently associated with necrosis or hemorrhage of components of the HPA axis. As a result of the limited venous drainage of the adrenal glands, sepsis-associated massive increase in arterial blood flow to these glands results in enlarged glands [50]. Adrenal necrosis and hemorrhage as a consequence of sepsis has been known for more than a century [51]. Predisposing factors of the so-called Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome include renal failure, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and treatment with anticoagulants or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ischemic lesions and hemorrhage have also been described within the hypothalamus or pituitary gland at postmortem examination in septic shock [52].

Altered CRH/ACTH synthesis

Hypothalamic/pituitary gland stimulation by cytokines, particularly IL-1, induces a biphasic response with initial proportional increase followed by progressive decline in anterior pituitary ACTH concentrations [53, 54]. In animal models [55] and in humans [56], sepsis is associated with marked overexpression of iNOS in hypothalamic nuclei that is partly triggered by TNF and IL-1. Subsequent abundant release of NO may cause apoptosis of neurons and glial cells in the neighborhood. Sepsis is also associated with decreased ACTH synthesis, though its secretagogues CRH and vasopressin remained unaltered [57]. Thus, the suppression in ACTH synthesis following sepsis may be mediated by NO [58]. In addition, feedback inhibition exerted by elevated circulating free cortisol, driven by ACTH-independent mechanisms and suppressed cortisol breakdown, can suppress ACTH [14, 15, 59].

ACTH synthesis can also be inhibited by several therapeutic agents such as glucocorticoids, opioid analgesics, azole antifungals (e.g., ketoconazole) or psychoactive drugs [60]. In animals, depending on the dose, timing and duration, opioids have been shown to variably stimulate or inhibit the CRH/ACTH axis, whereas in humans they predominantly inhibit it [61]. Both endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids exert negative feedback control on the HPA axis by suppressing hypothalamic CRH production and pituitary ACTH secretion. This suppression can render the adrenal glands unable to generate sufficient cortisol after glucocorticoid treatment is stopped. Abrupt cessation, or too rapid withdrawal, of glucocorticoid treatment may then cause symptoms of adrenal insufficiency [1, 21]. In non-ICU patients, even after a few days of glucocorticoid treatment, removal without tapering leads to adrenal suppression (measured with corticotropin test) in 45% of patients with gradual recovery over a period of 14 days [62]. Ample experimental and clinical evidence [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] shows that premature discontinuation of glucocorticoids in patients with severe sepsis or ARDS frequently (25–40%) leads to rebound systemic inflammation and clinical relapse (hemodynamic deterioration, recrudescence of ARDS, or worsening multiple organ dysfunction). Experimental animal sepsis models have demonstrated an early marked increase in ACTH levels that returns to baseline values at around 72 h [63]. Compared with healthy volunteers, clinical studies have found ACTH levels to be significantly lower in critically ill septic patients [14, 64, 65]. Decreased ACTH levels are observed during the first week of ICU stay [14, 15]. In septic patients, reduction in inflammatory cytokine levels correlates with increases in ACTH levels by ICU day 7–10 [21]. Altered ACTH synthesis in response to metyrapone was observed in roughly half of patients with septic shock and very occasionally in critically ill patients without sepsis [64]. The reduced ACTH secretion could also be secondary to changes in the feedback regulation of the HPA axis, as described below. Prolonged reduction of ACTH signaling within adrenocortical cells may result in adrenal atrophy [59].

Altered adrenal steroidogenesis

The adrenal storage of cortisol is very limited. Thus, an adequate adrenal response to stress relies almost entirely on cortisol synthesis. The HPA-axis response to sepsis has not been well defined. There is some evidence that cortisol production rate is somewhat increased in critically ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome [14]. As noted earlier, about half of patients with septic shock have decreased cortisol synthesis as assessed by response to the metyrapone test [64]. Following administration of metyrapone, 60% of patients with septic shock had 11-deoxycortisol concentrations of less than 7 µg/dl, suggesting decreased corticosteroid synthesis by adrenocortical cells. The alteration may occur at various steps in the cortisol synthesis chain. Histological examination of the adrenal cortex of both animals and humans with sepsis found marked depletion in lipid droplets, suggesting deficiency in esterified cholesterol storage [66]. This sepsis-induced loss in lipid droplets is likely mediated by annexin A1 and formyl peptide receptors [67]. During critical illness, both increased plasma ACTH concentrations and depletion in adrenal cholesterol stores upregulate adrenal scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), an HDL receptor, which captures esterified cholesterol from blood [68]. SR-B1-mediated cholesterol uptake is considered as an essential protective mechanism against endotoxin [69]. In one study, sepsis induced-deficiency in SR-B1 expression by the adrenal cortex was associated with increased mortality [70].

A number of environmental factors may also have substantial inhibitory effects on adrenal steroidogenesis. Steroidogenesis may be inhibited at various enzymatic steps by drugs, including P-450 aromatase, hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase, or mitochondrial cytochrome P-450-dependent enzymes [60]. In critically ill patients undergoing rapid sequence intubation, the use of etomidate, a drug known to inhibit the last enzymatic step in cortisol synthesis, increased the risk of adrenal insufficiency between 4 and 6 h (OR 19.98; 95% CI 3.95–101.11) and at 12 h (OR 2.37; 95% CI 1.61–3.47) post-dosing [71]. This effect was associated with worsening in organ dysfunction but the ultimate effect on mortality remains unclear. Analgesia and sedation may also affect HPA-axis response in critical illness. Opioids administered to opioid-naive subjects rapidly and profoundly inhibit both stress-related cortisol production and cortisol response to cosyntropin stimulation, while chronic opioid consumers occasionally manifest adrenal crises, phenomena apparently induced by inhibition of the HPA axis at multiple sites [72]. Benzodiazepines, similarly, quickly induce diminished cortisol formation by inhibiting activity at multiple central and peripheral sites in the HPA axis, including that of adrenal microsomal 17- and 21-hydroxylase activity as well as 11-β-hydroxylase activity in adrenal mitochondria [73] Finally, experimental studies have shown that inflammatory mediators such as corticostatins may bind to ACTH receptors in the adrenal cortex, thus preventing ACTH stimulation of cortisol synthesis [74].

Altered extra-adrenal corticosteroid metabolism

There is evidence for altered activity of corticosteroid-metabolizing enzymes during inflammation and critical illness. These changes can influence local tissue action of glucocorticoids and impact the activity of the HPA axis. Even though daytime cortisol production rate is increased in sepsis, the absolute increase appears much less than previously thought. Also, nocturnal cortisol production is not different from that in healthy subjects [15] despite the level of cortisol in the circulation increasing. Several studies have also demonstrated that the half-life of cortisol is dramatically increased during severe sepsis and other critical illnesses [14, 15]. All of these findings suggest that reduced cortisol breakdown may be a major feature of sepsis. Experiments involving a range of in vivo and ex vivo techniques showed that the expression and activity of the glucocorticoid-inactivating 5-reductase enzymes are decreased [14]. Additional studies demonstrate that reduced metabolism of cortisol impacted the pulsatile release of ACTH [15]. Post-mortem studies of patients who died after prolonged sepsis demonstrate reduced adrenal cortical size and changes in adrenal morphology in keeping with reduced exposure of the adrenal cortex to ACTH [59]. These results suggest that some of the long-term changes in the HPA axis associated with critical illness are due to altered metabolism of cortisol that leads to reduced capacity for future cortisol secretion in response to stress. Other studies examining endocrine testing during prolonged critical illness may need re-evaluation in the light of this altered physiology.

Tissue resistance to glucocorticoids

Besides the availability of cortisol, the sensitivity of target tissues to cortisol is important in the regulation of cortisol bioactivity. Intracellular glucocorticoid resistance refers to inadequate glucocorticoid receptor alpha (GR-α) activity despite seemingly adequate plasma cortisol concentrations [75]. Since the GR-α ultimately controls GC-mediated activity, any condition that affects its binding affinity, concentration, transport to the nucleus, and interactions with GRE (nuclear and mitochondrial) or other relevant transcription factors (NF-kB, AP-1) and co-regulators can eventually affect the response of cells to glucocorticoids [75]. Tissue resistance to glucocorticoids has been implicated in chronic inflammatory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, severe asthma, systemic lupus erythematosus, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis [76]. Glucocorticoid resistance is also recognized as a potential complication of critical illness, with most of the evidence originating from the sepsis and ARDS clinical and experimental literature [75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Critical illness is associated with reduced GR-α density and transcription [7, 25, 82, 83] and increased GR-β (dominant negative activity on GR-induced transcription) [80, 83, 84]. These changes are considered maladaptive, since GR-α upregulation was shown to augment the effects of available glucocorticoids [81]. Clinical studies in patients with septic shock [79, 80] and ARDS [7] have provided evidence of an association between the degree of intracellular glucocorticoid resistance, disease severity, and mortality.

Ex vivo experiments suggest that, in ARDS, insufficient GC-GRα-mediated activity is a central mechanism for the upregulation of NF-kB activity [7, 81]. Plasma samples from patients with declining inflammatory cytokine levels (and thus a state of regulated systemic inflammation) over time elicited a progressive increase in GC-GRα-mediated activity (GRα binding to NF-kB and to glucocorticoid response elements on DNA, stimulation of inhibitory protein IκBα and of IL-10 transcription) and a corresponding reduction in NF-kB nuclear binding and transcription of TNF-α and IL-1β. In contrast, plasma samples from patients with sustained elevation in inflammatory cytokine levels elicited only modest longitudinal increases in GC-GRα-mediated activity and a progressive increase in NF-kB nuclear binding over time that was most striking in non-survivors (suggesting a dysregulated, NF-kB-driven response). Analysis of lung tissue obtained by open lung biopsy demonstrated that the degree of NF-kB and GRα activation was associated with histological progression of ARDS, with positive correlation between severity of fibroproliferation and nuclear uptake of NF-kB and a lower ratio of GRα: NF-kB nuclear uptake [7]. Similarly, in experimental ARDS, lung tissue demonstrated reduced GRα expression and increased GRβ expression, leading to decreased GRα nuclear translocation [84].

The effect of exogenous glucocorticoids on intracellular glucocorticoid resistance was studied in both circulating and tissue cells. In experimental ARDS, low-dose glucocorticoid treatment compared with placebo restored GRα number and function with resolution of pulmonary inflammation [7]. Similarly, in an ex vivo ARDS study, prolonged methylprednisolone treatment—contrary to placebo—was associated with upregulation in GRα number, GRα binding to NF-kB, GRα nuclear translocation leading to reduction in NF-kB DNA-binding and transcription of inflammatory cytokines [81]. Treatment with glucocorticoids led to a change in the longitudinal direction of systemic inflammation from dysregulated (NF-kB-driven response, maladaptive lung repair) to regulated (GRα-driven response, adaptive lung repair), with significant reduction in indices of alveolar-capillary membrane permeability and markers of inflammation, hemostasis, and tissue repair.

Sepsis is characterized by decreased GR-α in circulating cells, in liver and muscle [25, 82, 83]. In addition there is decreased GR-α transcription in circulating cells and lymph node/spleen, in liver and kidney, and lung tissue [77]. Sepsis is also characterized by an increased expression of the GR isoform GR-β in circulating cells, resulting in an imbalance between GRα and GRβ [80, 83]. All these changes are likely to contribute to corticosteroid resistance at a tissue level. Tissue resistance to corticosteroid is highly variable and correlates with severity of illness and mortality [85].

Summary

Three major pathophysiologic events account for CIRCI: dysregulation of the HPA axis, altered cortisol metabolism, and tissue resistance to corticosteroids (Table 1). During critical illness, the regulation of cortisol production becomes much more complex, involving multidirectional crosstalk between the CRH/ACTH pathways, autonomic nervous system, vasopressinergic system, and immune system. Recent studies have shown that plasma clearance of cortisol is markedly reduced during critical illness, explained by suppressed expression and activity of the main cortisol-metabolizing enzymes in liver and kidney. Additionally, cortisol production rate in critically ill patients is only moderately increased to less than double that of matched healthy subjects. In the face of low plasma ACTH concentrations, these data suggest that other factors drive hypercortisolism during critical illness, which may suppress ACTH by feedback inhibition. Finally, intracellular glucocorticoid resistance from insufficient GR-α-mediated anti-inflammatory activity (reduced GR-α density and transcription) and an increased expression of GR-β in circulating cells resulting in an imbalance between GRα and GRβ can be found in critically ill patients despite seemingly adequate circulating cortisol levels. These new insights add to the limitations of the current diagnostic tools to identify patients at risk for CIRCI and may also impact how corticosteroids are used in patients with CIRCI.

References

Marik PE, Pastores SM, Annane D, American College of Critical Care Medicine et al (2008) Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 36(6):1937–1949

Nicolaides NC, Kyratzi E, Lamprokostopoulou A, Chrousos GP, Charmandari E (2015) Stress, the stress system and the role of glucocorticoids. NeuroImmunoModulation 22(1–2):6–19

Meduri GU, Annane D, Chrousos GP, Marik PE, Sinclair SE (2009) Activation and regulation of systemic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest 136(6):1631–1643

Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, Harris AG, Chrousos GP (2005) Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. NeuroImmunoModulation 12(5):255–269

Suffredini AF, Fantuzzi G, Badolato R, Oppenheim JJ, O’Grady NP (1999) New insights into the biology of the acute phase response. J Clin Immunol 19(4):203–214

Friedman R, Hughes AL (2002) Molecular evolution of the NF-kappaB signaling system. Immunogenetics 53(10–11):964–974

Meduri GU, Muthiah MP, Carratu P, Eltorky M, Chrousos GP (2005) Nuclear factor-kappa B- and glucocorticoid receptor alpha-mediated mechanisms in the regulation of systemic and pulmonary inflammation during sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence for inflammation-induced target tissue resistance to glucocorticoids. NeuroImmunoModulation 12(6):321–338

Lee SR, Kim HK, Song IS et al (2013) Glucocorticoids and their receptors: insights into specific roles in mitochondria. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 112(1–2):44–54

Galon J, Franchimont D, Hiroi N et al (2002) Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. FASEB J 16(1):61–71

Li-Tempel T, Larra MF, Sandt E et al (2016) The cardiovascular and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress is controlled by glucocorticoid receptor sequence variants and promoter methylation. Clin Epigenet 8:12

Midzak A, Papadopoulos V (2016) Adrenal mitochondria and steroidogenesis: from individual proteins to functional protein assemblies. Front Endocrinol 7:1–14

Esteban NV, Loughlin T, Yergey AL, Zawadzki JK, Booth JD, Winterer JC, Loriaux DL (1991) Daily cortisol production rate in man determined by stable isotope dilution/mass spectrometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72(1):39–45

Vassiliadi DA, Dimopoulou I, Tzanela M et al (2014) Longitudinal assessment of adrenal function in the early and prolonged phases of critical illness in septic patients: relations to cytokine levels and outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(12):4471–4480

Boonen E, Vervenne H, Meersseman P et al (2013) Reduced cortisol metabolism during critical illness. N Engl J Med 368(16):1477–1488

Boonen E, Meersseman P, Vervenne H et al (2014) Reduced nocturnal ACTH-driven cortisol secretion during critical illness. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306(8):E883–E892

Nenke MA, Rankin W, Chapman MJ et al (2015) Depletion of high-affinity corticosteroid-binding globulin corresponds to illness severity in sepsis and septic shock; clinical implications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 82(6):801–807

Beishuizen A, Thijs LG, Vermes I et al (2001) Patterns of corticosteroid-binding globulin and the free cortisol index during septic shock and multitrauma. Intensive Care Med 27:1584–1591

Tomlinson JW, Moore J, Cooper MS et al (2001) Regulation of expression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in adipose tissue: tissue-specific induction by cytokines. Endocrinology 142:1982–1989

Cai TQ, Wong B, Mundt SS et al (2001) Induction of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 but not -2 in human aortic smooth muscle cells by inflammatory stimuli. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 77:117–122

Hapgood JP, Avenant C, Moliki JM (2016) Glucocorticoid-independent modulation of GR activity: implications for immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther 165:93–113

Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP (2014) Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 383(9935):2152–2167

Cain DW, Cidlowski JA (2017) Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Immunol 17(4):233–247

Goodwin JE, Feng Y, Velazquez H, Sessa WC (2013) Endothelial glucocorticoid receptor is required for protection against sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(1):306–311

Goodwin JE, Feng Y, Velazquez H, Zhou H, Sessa WC (2014) Loss of the endothelial glucocorticoid receptor prevents the therapeutic protection afforded by dexamethasone after LPS. PLoS One 9(10):e108126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108126

Peeters RP, Hagendorf A, Vanhorebeek I et al (2009) Tissue mRNA expression of the glucocorticoid receptor and its splice variants in fatal critical illness. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 71(1):145–153

Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA (2013) The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 132(5):1033–1044

Boonen E, Bornstein SR, Van den Berghe G (2015) New insights into the controversy of adrenal function during critical illness. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3(10):805–815

Le Tulzo Y, Pangault C, Amiot L et al (2004) Monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR transcriptional downregulation by cortisol during septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169(10):1144–1151

Keh D, Boehnke T, Weber-Cartens S et al (2003) Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of “low-dose” hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167:512–520

Arnalich F, Garcia-Palomero E, López J et al (2000) Predictive value of nuclear factor kappa B activity and plasma cytokine levels in patients with sepsis. Infect Immun 68(4):1942–1945

Lee YL, Chen W, Chen LY, Chen CH, Lin YC, Liang SJ, Shih CM (2010) Systemic and bronchoalveolar cytokines as predictors of in-hospital mortality in severe community-acquired pneumonia. J Crit Care 25(1):176.e7–176.e13

Gomez HG, Gonzalez SM, Londoño JM et al (2014) Immunological characterization of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome in patients with severe sepsis: a longitudinal study. Crit Care Med 42(4):771–780

Fernandez-Botran R, Uriarte SM, Arnold FW et al (2014) Contrasting inflammatory responses in severe and non-severe community-acquired pneumonia. Inflammation. 37(4):1158–1166

Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP et al (2007) GenIMS Investigators. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Arch Intern Med 167(15):1655–1663

Meduri GU, Headley S, Kohler G, Stentz F, Tolley E, Umberger R, Leeper K (1995) Persistent elevation of inflammatory cytokines predicts a poor outcome in ARDS. Plasma IL-1 beta and IL-6 levels are consistent and efficient predictors of outcome over time. Chest 107(4):1062–1073

Meduri GU, Kohler G, Headley S, Tolley E, Stentz F, Postlethwaite A (1995) Inflammatory cytokines in the BAL of patients with ARDS. Persistent elevation over time predicts poor outcome. Chest 108(5):1303–1314

Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J et al (2011) A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med 208(13):2581–2590

Aisiku IP, Yamal JM, Doshi P et al (2016) Plasma cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 are associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care 20:288

Yende S, D’Angelo G, Kellum JA, GenIMS Investigators et al (2008) Inflammatory markers at hospital discharge predict subsequent mortality after pneumonia and sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177(11):1242–1247

Dunn AJ (2000) Cytokine activation of the HPA axis. Ann NY Acad Sci 917:608–617 (review)

Besedovsky H, del Rey A, Sorkin E, Dinarello CA (1986) Immunoregulatory feedback between interleukin-1 and glucocorticoid hormones. Science 233(4764):652–654

Kanczkowski W, Sue M, Zacharowski K, Reincke M, Bornstein SR (2015) The role of adrenal gland microenvironment in the HPA axis function and dysfunction during sepsis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 408:241–248

Darling G, Goldstein DS, Stull R, Gorschboth CM, Norton JA (1989) Tumor necrosis factor: immune endocrine interaction. Surgery 106(6):1155–1160

Mikhaylova IV, Kuulasmaa T, Jääskeläinen J, Voutilainen R (2007) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates steroidogenesis, apoptosis, and cell viability in the human adrenocortical cell line NCI-H295R. Endocrinology 148(1):386–392

Jäättelä M, Carpén O, Stenman UH, Saksela E (1990) Regulation of ACTH-induced steroidogenesis in human fetal adrenals by rTNF-alpha. Mol Cell Endocrinol 68(2–3):R31–R36

Jäättelä M, Ilvesmäki V, Voutilainen R, Stenman UH, Saksela E (1991) Tumor necrosis factor as a potent inhibitor of adrenocorticotropin-induced cortisol production and steroidogenic P450 enzyme gene expression in cultured human fetal adrenal cells. Endocrinology 128(1):623–629

Engström L, Rosen K, Angel A et al (2008) Systemic immune challenge activates an intrinsically regulated local inflammatory circuit in the adrenal gland. Endocrinology 149:1436–1450

Bornstein SR, Zacharowski P, Schumann RR et al (2004) Impaired adrenal stress response in Toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(47):16695–16700

Kanczkowski W, Alexaki VI, Tran N et al (2013) Hypothalamo-pituitary and immune-dependent adrenal regulation during systemic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:14801–14806

Jung B, Nougaret S, Chanques G et al (2011) The absence of adrenal gland enlargement during septic shock predicts mortality: a computed tomography study of 239 patients. Anesthesiology 115:334–343

Waterhouse R (1911) A case of suprarenal apoplexy. Lancet 1:577–578

Sharshar T, Annane D, de la Grandmaison GL, Brouland JP, Hopkinson NS, Francoise G (2004) The neuropathology of septic shock. Brain Pathol 14(1):21–33

Mélik Parsadaniantz S, Levin N, Lenoir V, Roberts JL, Kerdelhué B (1994) Human interleukin 1 beta: corticotropin releasing factor and ACTH release and gene expression in the male rat: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Neurosci Res 37(6):675–682

Parsadaniantz SM, Batsché E, Gegout-Pottie P, Terlain B, Gillet P, Netter P, Kerdelhué B (1997) Effects of continuous infusion of interleukin 1 beta on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), CRH receptors, proopiomelanocortin gene expression and secretion of corticotropin, beta-endorphin and corticosterone. Neuroendocrinology 65(1):53–63

Wong ML, Rettori V, al-Shekhlee A et al (1996) Inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression in the brain during systemic inflammation. Nat Med 2(5):581–584

Sharshar T, Gray F, Lorin de la Grandmaison G et al (2003) Apoptosis of neurons in cardiovascular autonomic centres triggered by inducible nitric oxide synthase after death from septic shock. Lancet 362(9398):1799–1805

Polito A, Sonneville R, Guidoux C et al (2011) Changes in CRH and ACTH synthesis during experimental and human septic shock. PLoS One 6:e25905

McCann SM, Kimura M, Karanth S, Yu WH, Mastronardi CA, Rettori V (2000) The mechanism of action of cytokines to control the release of hypothalamic and pituitary hormones in infection. Ann NY Acad Sci 917:4–18 (review)

Boonen E, Langouche L, Janssens T et al (2014) Impact of duration of critical illness on the adrenal glands of human intensive care patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:1569–1582

Bornstein SR (2009) Predisposing factors for adrenal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 360:2328–2339

Vuong C, Van Uum SH, O’Dell LE, Lutfy K, Friedman TC (2010) The effects of opioids and opioid analogs on animal and human endocrine systems. Endocr Rev 31(1):98–132

Henzen C, Suter A, Lerch E, Urbinelli R, Schorno XH, Briner VA (2000) Suppression and recovery of adrenal response after short-term, high-dose glucocorticoid treatment. Lancet 355(9203):542–545

Cortés-Puch I, Hicks CW, Sun J et al (2014) Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in lethal canine Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307(11):E994–E1008

Annane D, Maxime V, Ibrahim F, Alvarez JC, Abe E, Boudou P (2006) Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in severe sepsis and septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:1319–1326

Vermes I, Beishuizen A, Hampsink RM, Haanen C (1995) Dissociation of plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol levels in critically ill patients: possible role of endothelin and atrial natriuretic hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80(4):1238–1242

Polito A, Lorin de la Grandmaison G, Mansart A et al (2010) Human and experimental septic shock are characterized by depletion of lipid droplets in the adrenals. Intensive Care Med 36(11):1852–1858

Buss NA, Gavins FN, Cover PO, Terron A, Buckingham JC (2015) Targeting the annexin 1-formyl peptide receptor 2/ALX pathway affords protection against bacterial LPS-induced pathologic changes in the murine adrenal cortex. FASEB J 29(7):2930–2942

Wang N, Weng W, Breslow JL, Tall AR (1996) Scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) is up-regulated in adrenal gland in apolipoprotein A-I and hepatic lipase knock-out mice as a response to depletion of cholesterol stores. In vivo evidence that SR-BI is a functional high density lipoprotein receptor under feedback control. J Biol Chem 271(35):21001–21004

Cai L, Ji A, de Beer FC, Tannock LR, van der Westhuyzen DR (2008) SR-BI protects against endotoxemia in mice through its roles in glucocorticoid production and hepatic clearance. J Clin Investig 118(1):364–375

Gilibert S, Galle-Treger L, Moreau M et al (2014) Adrenocortical scavenger receptor class B type I deficiency exacerbates endotoxic shock and precipitates sepsis-induced mortality in mice. J Immunol 193(2):817–826

Bruder EA, Ball IM, Ridi S, Pickett W, Hohl C (2015) Single induction dose of etomidate versus other induction agents for endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD010225

Daniell HW (2008) Opioid contribution to decreased cortisol levels in critical care patients. Arch Surg 143(12):1147–1148

Thomson I, Fraser R, Kenyon CJ (1995) Regulation of adrenocortical steroidogenesis by benzodiazepines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 53:75–79

Tominaga T, Fukata J, Naito Y et al (1990) Effects of corticostatin-I on rat adrenal cells in vitro. J Endocrinol 125(2):287–292

Dendoncker K, Libert C (2017) Glucocorticoid resistance as a major drive in sepsis pathology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 35:85–96

Marik PE (2009) Critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency. Chest 135(1):181–193

Bergquist M, Nurkkala M, Rylander C et al (2013) Expression of the glucocorticoid receptor is decreased in experimental Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. J Infect 67:574–583

Bergquist M, Lindholm C, Strinnholm M et al (2015) Impairment of neutrophilic glucocorticoid receptor function in patients treated with steroids for septic shock. Intensive Care Med Exp 3:23

Vardas K, Ilia S, Sertedaki A et al (2017) Increased glucocorticoid receptor expression in sepsis is related to heat shock proteins, cytokines, and cortisol and is associated with increased mortality. Intensive Care Med Exp. 5(1):10

Guerrero J, Gatica HA, Rodriguez M, Estay R, Goecke IA (2013) Septic serum induces glucocorticoid resistance and modifies the expression of glucocorticoid isoforms receptors: a prospective cohort study and in vitro experimental assay. Crit Care 17(3):R107

Meduri GU, Tolley EA, Chrousos GP, Stentz F (2002) Prolonged methylprednisolone treatment suppresses systemic inflammation in patients with unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: evidence for inadequate endogenous glucocorticoid secretion and inflammation-induced immune cell resistance to glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165(7):983–991

van den Akker EL, Koper JW, Joosten K, de Jong FH, Hazelzet JA, Lamberts SW, Hokken-Koelega AC (2009) Glucocorticoid receptor mRNA levels are selectively decreased in neutrophils of children with sepsis. Intensive Care Med 35(7):1247–1254

Ledderose C, Möhnle P, Limbeck E et al (2012) Corticosteroid resistance in sepsis is influenced by microRNA-124—induced downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor-α. Crit Care Med 40(10):2745–2753

Kamiyama K, Matsuda N, Yamamoto S et al (2008) Modulation of glucocorticoid receptor expression, inflammation, and cell apoptosis in septic guinea pig lungs using methylprednisolone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295(6):L998–L1006

Cohen J, Pretorius CJ, Ungerer JP (2016) Glucocorticoid sensitivity is highly variable in critically ill patients with septic shock and is associated with disease severity. Crit Care Med 44(6):1034–1041

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the assistance of Susan Weil-Kazzaz, CMI, Manager, Design and Creative Services, Department of Communications, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY for preparation of the figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Annane has been involved with research relating to this guideline. Dr. Pastores participates in the American College of Physicians: Speaker at ACP Critical Care Update Precourse, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) (faculty speaker at Annual Congress), the American Thoracic Society (ATS): Moderator at Annual Meeting, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (EISCM) (co-chair of Corticosteroid Guideline in collaboration with SCCM), and the Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine (co-director and speaker at Multiprofessional Critical Care Board Review Course). He has spoken on the topic of corticosteroid use in critical illness and specifically in sepsis at the International Symposium in Critical and Emergency Medicine in March 2017. Dr. Arlt participates in the Society for Endocrinology UK (Chair of the Clinical Committee, member of Council, member of the Nominations Committee) and the Endocrine Society USA (member, Publication Core Committee). Dr. Briegel participates in the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the Deutsche interdisziplinäre Vereinigung Intensivmedizin, and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesie und Intensivmedizin, and he has given lectures and talks on hydrocortisone treatment of septic shock. Dr. Cooper participates in a range of specialist societies relating to endocrinology and bone disease. Dr. Meduri disclosed he is a government employee. Dr. Olsen participates in the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (grant review committee), and he represents the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists on the National Quality Forum for Surgery Measures. Dr. Rochwerg disclosed he is a methodologist for ATS, CBS, ESCIM, ASH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

This article is linked to another article entitled “Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM): 2017” published in parallel (doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4919-5).

Full author information and disclosures are available at the end of the article.

This article is being simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine (doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002724) and Intensive Care Medicine.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Annane, D., Pastores, S.M., Arlt, W. et al. Critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI): a narrative review from a Multispecialty Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Intensive Care Med 43, 1781–1792 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4914-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4914-x