Abstract

Purpose

Critically ill patients are often unable to give informed consent to participate in clinical research. A process of delayed consent, enrolling patients into clinical trials and obtaining consent as soon as practical from either the participant or their substitute decision maker, has sometimes been used. The objective of this study was to determine the opinion of participants, previously enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study, of the delayed consent process.

Methods

This observational study was conducted from 2009 to 2010 in the ICU of a tertiary referral hospital in Australia. Participants who were enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study with delayed consent who survived, were cognitively intact, and proficient in English were posted a questionnaire regarding their opinion of the delayed consent process. The questionnaire was returned by post, fax, email, or completed during a telephone interview.

Results

Of 298 eligible participants, 210 responded, with an overall response rate of 79 %. Delayed consent to participate in the NICE-SUGAR study was obtained from participants (57/210; 27.1 %) or the substitute decision maker (152/210; 72.4 %). Most respondents (195/204; 95.6 %) would have consented to participate in the NICE-SUGAR study if asked before enrolment; most (163/198; 82.3 %) ranked first “the person who consented on their behalf for the NICE Study” as most preferred to make decisions, should they be unable; and most (177/202; 87.6 %) agreed with the decision made by their relative.

Conclusion

Delayed consent to participate in a clinical trial that includes critically ill patients is acceptable from research participant’s perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The provision of informed consent by patients before enrolment into a clinical trial is essential for the ethical conduct of clinical research. However, there are populations of patients who are unable to provide informed consent before enrolment in trials. Critically ill patients are one such group, as the nature of their illness and the treatments required often render them incapable of understanding the nature of the research as well as the risks and benefits involved and often prevent them from communicating their preferences. The need for immediate treatment can mean that patients or their substitute decision makers do not have the time necessary to make informed decisions, and it can be difficult to access the substitute decision maker in time to enroll the patient into a clinical trial [1, 2]. When available, substitute decision makers can be emotionally overwhelmed from the circumstances of the patient’s illness and have been reported to experience anxiety, depression, and fatigue [3–5], such that they are unable to consider participation of the patient in research [6].

Delayed consent involves the enrolment of patients who lack decision making capacity into a clinical trial before obtaining consent. Written informed consent to continue participation and for use of study-related data is obtained subsequently either from the substitute decision maker or from the patient themselves when they recover. Delayed consent has been used in large clinical trials including critically ill participants [7–9]. These studies have contributed to improving care for critically ill patients. In Australia ethics committees may approve enrolment of critically ill patients without prior consent in interventional research when participation is in the best interests of the patient and possible risks are justified by potential personal benefits [10].

While some ethics committees are willing to allow this form of consent, others are not [7]. The basis for these differences is not known. Knowledge of attitudes and preferences of patients in this situation may help inform ethics committees in these decisions. In particular, there is little known about the opinions of patients who have been enrolled in clinical studies without prior consent. Previous research in this area has used hypothetical scenarios and relatives of critically ill patients to gauge the acceptability of this practice [11–14]. No study has yet ascertained the views of patients who were enrolled into actual clinical trials using delayed consent. Therefore, we sought to determine the opinions of patients who were enrolled into a critical care clinical trial using delayed consent regarding the delayed consent process and the decisions to consent made by the substitute decision maker.

Methods

Participants and setting

The normoglycemia in intensive care-survival using glucose algorithm regulation (NICE-SUGAR) study was a multicenter randomised controlled trial that enrolled 6,104 patients and was conducted in the intensive care units (ICU) of 42 hospitals located in Australia, New Zealand, and North America. Details of the NICE-SUGAR study protocol [15] and results [7] are reported elsewhere. In brief, eligible adult participants were randomly assigned to one of two strategies for maintenance of blood glucose levels, either intensive or conventional blood glucose of 4.6–6.0 or 10.0 mmol per liter or less, respectively, while receiving treatment in the ICU. Patients were enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study from the ICU at the Royal North Shore Hospital between December 2004 and November 2008. The Royal North Shore Hospital is a metropolitan teaching hospital in Sydney with three adult ICUs, a 24-bed general ICU, a 9-bed cardiothoracic ICU, and an 8-bed neurosurgical ICU. This study was conducted between September 2009 and June 2010.

Participants were eligible for this study if they were enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study under the provision of delayed consent, with consent provided at a later date by either themselves or a substitute decision maker, or later withdrawn from the NICE-SUGAR study treatment by the substitute decision maker with consent provided for use of study-related data. Participants were excluded if they were enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study with written informed consent obtained before randomisation, judged to have insufficient English language skills to complete the questionnaire, or had limited cognitive capacity when screened for this study. Please see the Online Resource for methods related to cognitive screening. The Human Research Ethics Committees of the Hospital and of the University of Technology, Sydney, gave approval for this study. Informed consent from participants in this study was implied by completion and return of the questionnaire.

Questionnaire

A printed self-report questionnaire was designed specifically for this study. Please see the Online Resource for a copy of the questionnaire (Appendix A) and a detailed description of the development process. The questionnaire contained 12 items with forced choice responses and two open-ended questions. Self-reported feelings regarding the circumstances of enrolment in the NICE-SUGAR study were measured on four semantic differential rating scales with anchors of: fair-unfair; content-discontented; pleased-displeased; and angry-delighted. Participant’s responses on each scale were treated as Visual Analogue Scale data ranging from 0 to 100 mm. Agreement with selection of substitute decision maker, decisions made on their behalf, and altruistic motivations were measured on a five-point Likert scale; options ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree. A list of eight alternative persons or organisations to make decisions on their behalf was provided and respondents ranked them from one to eight, according to their first preference. Characteristics derived from the literature included education level [12], language spoken at home [4], main activity before the ICU admission [14], the duration of the relationship with the substitute decision maker, whether previous discussions regarding participation in research had occurred [12] and one question regarding their general health [16].

A panel of volunteers made up of 17 health care professionals including intensive care specialists, senior nurses, a nurse researcher, research coordinators, social workers, a chaplain, administrative personnel, and lay persons associated with the ICU, reviewed the face validity and content validity of the questionnaire. Two rounds of pilot testing were undertaken to assist in item generation, to ensure that questions had sufficient responses from which to choose, and to identify items that were poorly worded or were difficult to understand.

Data additional to that obtained directly from respondents were collected from retrospective chart review of the medical records, ICU databases, the NICE-SUGAR study site case report files, and consent documents.

Procedures

A three-stage recruitment procedure was used. Stage one involved initial contact via telephone to briefly introduce this study and to obtain the best postal address for the information package. This package was addressed to the individual and included: a comprehensive cover letter; a copy of the signed NICE-SUGAR study consent form, because it was anticipated that former ICU patients may not recall they had been in the clinical trial or remember (or be aware of) the identity of the person who provided consent on their behalf; the questionnaire; and a one-page plain language summary of the NICE-SUGAR study results with information regarding their allocation to either intensive or conventional groups. The investigator (JP) conducted the initial telephone contact and followed an objective telephone transcript approved by the ethics committee to minimise potential personal bias.

At stage two, all people who had not returned the questionnaire within 3 weeks received a reminder telephone call, when they were offered the opportunity to complete the survey by telephone or to return it via fax or email. People who were unable to complete the written form because of time or to physical constraints were invited to complete the questionnaire during a structured telephone interview with an independent research nurse experienced in contacting former ICU patients. Verbal assent for completion with the research nurse was obtained by the investigator. The final contact was 3 weeks later when non-responders were reposted the information. If this last contact was unsuccessful, no further attempts were made to obtain follow-up.

Data analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, 1997) spreadsheet and subsequently analysed using PASW® Statistics GradPack 18 (SPSS, 2009). No assumptions were made regarding missing data. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The free text comments to the open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim and content analysis was used to systematically interpret responses. Exact words from the participant’s comments were noted and their frequencies counted. Similar or related words were confirmed in a thesaurus and grouped into categories. If more than one idea was identified in a response, the main idea was used for categorisation. The selection of categories was independently checked by two investigators. Agreement about categorisation was reached by discussion when there were differences in judgement.

Results

Participants

There were 634 ICU patients enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study at the study hospital. Of these people, 53.0 % were ineligible for this study (Fig. 1). Questionnaires were completed by 210 former participants in the NICE-SUGAR study, yielding a response rate of 79 %. The median (IQR) time from enrolment in the NICE-SUGAR study to the date the questionnaire was completed was 153 (116.7–191) weeks. When completing the questionnaire over half of respondents reported their general health was good (68/210; 32.4 %) or very good (59/210; 28.1 %) with one quarter indicating fair (54/210; 25.7 %) or poor (16/210; 7.6 %). Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondents and those who did not participate in this study. There were no significant differences in diagnostic categories between respondents and non-respondents or declined groups. Table 2 displays the demographic characteristics of respondents. Half of respondents reported their highest education level as greater than high school. Table 3 summarises the providers of and characteristics of delayed consent for the NICE-SUGAR study. The substitute decision maker had provided delayed consent for over 70 % of respondents. Of those respondents, approximately one quarter reported they previously had held discussions with their substitute decision maker regarding participation in research. Subsequent results are presented as the total number of responses to each question.

Opinions of delayed consent

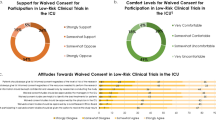

A majority of 195/204 (95.6 %) respondents answered “Yes” they would have consented to participate in the NICE-SUGAR study before enrolment if they could have been asked. Respondent characteristics were examined for relationships to the responses with demographic or other factors including the respondent’s age, gender, level of education, prior employment, and allocated treatment group in the NICE-SUGAR study. More women (7/75; 9.3 %) than men (2/129; 1.6 %) responded “No” to whether they would have consented to participation (p = 0.013). Figure 2 displays the distribution of responses regarding feelings of enrolment in the NICE-SUGAR study using delayed consent, positively skewed towards delighted, pleased, content, and fair. A small proportion of respondents selected “don’t know” regarding delighted-angry (16/153; 10.5 %), pleased-displeased (14/170; 8.2 %), content-discontented (10/167; 6.0 %), and fair-unfair (15/170; 8.8 %).

In response to the question “What were your thoughts when you found out that you had been enrolled in the blood sugar (NICE) study?” most (202/210; 96.1 %) provided textual responses that were grouped into categories of similar content. Many respondents reported positively “not worried” (47/202; 23.3 %), “happy” (37/202; 18.3 %), and “good” (7/202; 3.5 %) or were “neutral” (13/202; 6.4 %). Some respondents reported “surprise” (24/202; 11.9 %) and a similar proportion (23/202; 11.4 %) reported “no recollection”. Altruistic beliefs were also reported “helped research, diabetes research” (20/202; 9.9 %) or simply “helped others” (18/202; 8.9 %). See the Online Resource (Appendix B) for the thematic grouping of verbatim textual responses.

In response to the question to rank their preferences for alternative people or organisations to make decisions on their behalf, most respondents (163/198; 82.3 %) ranked “the person who consented on my behalf for the NICE Study” first. Fewer preferred “the intensive care doctor looking after me” (29/173; 16.8 %), “another relative or friend” (12/174; 6.9 %), and “my general practitioner” (9/168; 5.4 %) first. Respondents who had provided delayed consent to the NICE-SUGAR study themselves were less likely to rank “the person who consented on my behalf” first (p < 0.001).

Table 4 presents respondent agreement with statements regarding selection and decisions of the substitute decision maker. Most (191/206; 92.7 %) respondents agreed the right person was asked to consent on their behalf. Most respondents (177/202; 87.6 %) agreed their relative or friend had made the same decision they would have made. Most respondents (187/201; 93 %) were content with the decision made by their relative or friend.

Discussion

This study ascertained the opinions of trial participants who were enrolled in a clinical trial of available standard treatments with delayed consent. An overwhelming majority of respondents were positive regarding their enrolment in the NICE-SUGAR study using delayed consent. Most respondents reported that they would have participated in the NICE-SUGAR study, had they been asked beforehand. They also reported that the right person had been chosen to make decisions on their behalf. They agreed the substitute decision maker had made the same decision as they would have and were content with that decision. These results support the use of delayed consent in clinical trials when informed consent cannot be obtained prior to randomisation, and the treatments that are being evaluated are already in routine clinical practice.

This study examined the opinions of actual participants in clinical research regarding the process of delayed consent and of consenting decisions made by the substitute decision maker. Surveys conducted to ascertain community [17] and former ICU patients’ [13] attitudes to consent for research in critically ill patients who lacked decision-making capacity found that most citizens expressed comfort with waived and deferred consent for a hypothetical low-risk scenario [17] and that most former ICU patients were agreeable or neutral about potential enrolment in hypothetical research using delayed consent [13]. That theoretical work is extended in this study through description of former participants in a clinical trial who were enrolled using delayed consent. Participants in this study preferred relatives to make consenting decisions on their behalf when they were unable. Relatives were mostly a spouse or partner and adult children, similar to the identity of relatives who provided consent for research in a Canadian ICU [6]. No patients or substitute decision makers withdrew or withheld consent for data usage subsequent to enrolment using delayed consent at the Royal North Shore Hospital. A survey of substitute decision makers who were approached for consent for research in ICU found those who had declined would have changed their decision to agree when asked 24–48 h later because of more time to consider the study and changes in the patient’s condition [6].

There are a number of strengths to this study, notably the high response rate to the survey. Also, the study enrolled former ICU patients who had participated in an actual randomised controlled trial, thereby including an ideal population. The use of an actual instead of a hypothetical trial is a key strength as respondents were likely to relate to the actual scenario because of its relevance to them. The study design combined quantitative and qualitative methods in a questionnaire that had undergone rigorous development. The free text responses provided added depth to the forced choice responses. The fact that there was a prolonged duration of time that elapsed between the enrolment of participants and the conduct of this survey implies that the favorable perspective of participants is maintained over the long term.

There are some weaknesses to this study. Those patients who had a good outcome may have reflected positively on research undertaken during their stay in ICU because of emotional factors from the ICU experience and subsequent recovery. Their survival may have positively influenced responses such that issues of consent and research were of secondary importance. There is the possibility that the participants who did not respond to the survey will have opinions that are different to those that did respond, although the high response rate limits this effect. Most respondents reported their first language as English, thus the findings may not be generalisable to non-English speakers. Additionally, we cannot determine whether there is a cultural determinant of responses, as we may have excluded “immigrants”. We were unable to capture the opinions of all patients whose substitute decision maker refused consent on their behalf to continue on the NICE-SUGAR study treatment to ascertain if they were also content with the decision for use of study-related data in that instance. Resource constraints limited this study to a single institution, and to a single RCT, which limits the generalisability of the results. The length of time that passed between the enrolment of the participants and the conduct of this survey leads to the possibility of recall bias.

Several of the findings of the study suggest further investigation. Further exploration is needed on the preferences of ICU patients for the optimum time to provide delayed consent to participate in research conducted when they are experiencing or recovering from critical illness. It would be important to obtain a broader sample of participants from other study centres, from other countries, and in other trials to increase the generalisability of this study.

The implication of the results of this study is that regulatory bodies and members of human research ethics committees should feel comfortable that former ICU patients endorsed enrolment in a clinical trial using the process of delayed consent. Many large ICU-based randomised controlled trials are not completed as planned because of slower than anticipated accrual of patients [18]. In the NICE-SUGAR study a large number of patients (n = 1,634) were eligible but not enrolled as they were unable to provide consent and local ethics committee regulations did not permit delayed consent [7]. This highlights the challenges in conducting high-quality research in the ICU environment and of the need for alternative models of consent to that of prior consent for research involving the critically ill [19]. The use of delayed consent for clinical trials in critically ill patients where the treatments being compared are already used in routine clinical practice is supported by the participants in this study.

Conclusion

The findings of this study contribute to the understanding of complex issues in the area of consent for research in intensive care. Most former ICU patients enrolled in the NICE-SUGAR study from the study hospital using delayed consent would have agreed to participate in the study had they been able to be asked. Most reported that consent had been sought from the person from whom they would have wished and that they were content with the decision made. This study supports the continued use of delayed consent in randomised controlled trials that evaluate available standard intensive care treatments in critically ill patients.

Abbreviations

- NICE-SUGAR:

-

Normoglycemia in intensive care evaluation-survival using glucose algorithm study

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- SDM:

-

Substitute decision maker

- HREC:

-

Human research ethics committee

References

Annane D, Outin H, Fisch C, Bellissant E (2004) The effect of waiving consent on enrollment in a sepsis trial. Intensive Care Med 30:321–324

Cooke CR, Erickson SE, Watkins TR, Matthay MA, Hudson LD, Rubenfeld GD (2010) Age, sex, and race-based differences among patients enrolled versus not enrolled in acute lung injury clinical trials. Crit Care Med 38:1450–1457

McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, Fontaine DK, Puntillo KA (2010) Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med 38:1078–1085

Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, Grassin M, Zittoun R, le Gall JR, Dhainaut JF, Schlemmer B, French FG (2001) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med 29:1893–1897

Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert PE, Cheval C, Coloigner M, Merouani A, Moulront S, Pigne E, Pingat J, Zahar JR, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E (2005) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care 20:90–96

Mehta S, Pelletier FQ, Brown M, Ethier C, Wells D, Burry L, Macdonald R (2012) Why substitute decision makers provide or decline consent for ICU research studies: a questionnaire study. Intensive Care Med 38:47–54

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY-S, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hebert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ (2009) Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 360:1283–1297

RENAL Replacement Therapy Study Investigators, Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, Lo S, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Myburgh J, Norton R, Scheinkestel C, Su S (2009) Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 361:1627–1638

SAFE Study Investigators, Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, French J, Myburgh J, Norton R (2004) A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 350:2247–2256

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, Australian Vice Chancellors’ Committee (2007) National statement on ethical conduct in human research. Australian Government. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/e72.pdf. Accessed 28 August 2010

Ciroldi M, Cariou A, Adrie C, Annane D, Castelain V, Cohen Y, Delahaye A, Joly LM, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Papazian L, Michel F, Barnes NK, Schlemmer B, Pochard F, Azoulay E, Famirea Study Group (2007) Ability of family members to predict patient’s consent to critical care research. Intensive Care Med 33:807–813

Coppolino M, Ackerson L (2001) Do surrogate decision makers provide accurate consent for intensive care research? Chest 119:603–612

Scales DC, Smith OM, Pinto R, Barrett KA, Friedrich JO, Lazar NM, Cook DJ, Ferguson ND (2009) Patients’ preferences for enrolment into critical-care trials. Intensive Care Med 35:1703–1712

Stephenson AC, Baker S, Zeps N (2007) Attitudes of relatives of patients in intensive care and emergency departments to surrogate consent to research on incapacitated participants. Crit Care Resusc 9:40–50

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators (2005) The normoglycemia in intensive care evaluation (NICE) (ISRCTN04968275) and survival using glucose algorithm regulation (SUGAR) Study: development, design and conduct of an international multi-center, open label, randomized controlled trial of two target ranges for glycemic control in intensive care unit patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 172:1358–1359

RAND Corporation RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 Questionnaire Items. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_core_survey.pdf. Accessed October 28 2008

Burns KE, Magyarody NM, Duffett M, Nisenbaum R, Cook DJ (2011) Attitudes of the general public toward alternative consent models. Am J Crit Care 20:75–83

Rose L, Burns KE, Smith OM, Marshall JC (2009) Quantifying threats to the feasibility of clinical trials in critically ill patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 179 (1 Meeting Abstracts): A1580

Burns KE, Zubrinich C, Marshall J, Cook D (2009) The ‘Consent to Research’ paradigm in critical care: challenges and potential solutions. Intensive Care Med 35:1655–1658

Acknowledgments

Assistance with telephone interviews: Rachel Foley and Rosalind Elliott, data collection: Mary Fien, Jane Bowey and Phil Johnson. Alisa Higgins assisted with cognitive screening. Lynette Newby provided the NICE-SUGAR result summary. Di Roche, Margaret Bramwell and Victoria Whitfield provided assistance with respondent issues. The authors thank the medical, nursing, and allied health professionals of the study ICU, in particular Ray Raper and Richard Lee.

This study was a substudy of the NICE-SUGAR study and is endorsed by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Clinical Trials Group (CTG).

Financial support was received from the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses and the Royal North Shore Hospital Nursing and Midwifery Scholarship, provided by the Skinner family.

Conflicts of interest

JP, SM, and AD have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service (AU RED Ref: 08/HAWKE/161/162) and the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) (2009-142). Consent was implied by completion and return of the questionnaire to the investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

For the NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and The George Institute for International Health NICE Study investigators.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

The NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators: The contribution of the ANZICS CTG, the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (CCCTG), the George Institute for International Health, and the investigators in the main NICE-SUGAR study is acknowledged. Please see the Online Resource for a list of The George Institute for International Health NICE Study investigators and the CCCTG SUGAR study investigators (Appendix C).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Potter, J.E., McKinley, S. & Delaney, A. Research participants’ opinions of delayed consent for a randomised controlled trial of glucose control in intensive care. Intensive Care Med 39, 472–480 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2732-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2732-8