Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine childhood neighbourhood quality, peer relationships, and trajectories of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese adults.

Methods

The data came from the longitudinal dataset from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS, 2011–2018). Depressive symptoms were measured repeatedly using the ten-item Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). Latent growth modelling was used to capture the trajectory of depressive symptoms by childhood neighbourhood quality, and peer relationships.

Results

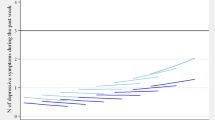

The mean level of depressive symptoms increased gradually in the follow-up period. Poorer childhood neighbourhood quality, and peer relationships were significantly associated with higher levels of depression in later life (β = 0.18 and β = 0.28 for aged 45–59, p < 0.001; β = 0.16 and β = 0.33 for aged 60 and over, p < 0.001) at baseline and a faster increase in depressive symptoms with age for childhood neighbourhood quality (β = 0.03, p < 0.01 for aged 45–59; β = 0.05, p < 0.01 for aged 60 and over). For males and females, poorer childhood neighbourhood quality, and peer relationships predicted higher levels of depression at baseline (β = 0.17 and β = 0.36 for males, p < 0.001; β = 0.16 and β = 0.27 for females, p < 0.001), and only neighbourhood quality was associated with a higher rate of change in depression during follow-up (β = 0.03, and β = 0.04, p < 0.05, respectively).

Conclusion

Poorer childhood neighbourhood quality was associated with the slope of change in depressive symptoms. Efforts towards improving childhood living conditions may help to prevent the detrimental health effects of such early life disadvantages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Researchers can access the CHARLS data via the link http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en/.

References

Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R et al (2014) Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 26(4):392–407

Almquist YB, Brännström L (2014) Childhood peer status and the clustering of social, economic, and health-related circumstances in adulthood. Soc Sci Med 105:67–75

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB et al (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med 10(2):77–84

Angelini V, Howdon DDH, Mierau JO (2019) Childhood socioeconomic status and late-adulthood mental health: results from the survey on health, ageing and retirement in Europe. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 74(1):95–104

Baranyi G, Sieber S, Pearce J et al (2019) A longitudinal study of neighbourhood conditions and depression in ageing European adults: do the associations vary by exposure to childhood stressors? Prev Med 126:105764

Barr PB (2018) Early neighborhood conditions and trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and into adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research 35:57–68

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG (2003) The anatomy of loneliness. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 12(3):71–74

Carrière I, Gutierrez LA, Pérès K et al (2011) Late life depression and incident activity limitations: influence of gender and symptom severity. J Affect Disord 133(1):42–50

Chen H, Mui AC (2014) Factorial validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale short form in older population in China. Int Psychogeriatr 26(1):49

Chen H, Xiong P, Chen L et al (2020) Childhood neighborhood quality, friendship, and risk of depressive symptoms in adults: the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 276:732–737

Erikson EH (1993) Childhood and society. WW Norton & Company.

Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore JA (2003) Cumulative disadvantage and health: long-term consequences of obesity? Am Sociol Rev 68(5):707

Ferraro KF, Schafer MH, Wilkinson LR (2015) Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: early imprints on physical health? Am Sociol Rev 81(1):107–133

Ferraro KF, Shippee TP (2009) Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist 49(3):333–343

Font SA, Maguire-Jack K (2016) Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: the role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl 51:390–399

Fryers T, Brugha T (2013) Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 9:1–50

Gotlib IH, Joormann J (2010) Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:285–312

Greene G, Fone D, Farewell D et al (2019) Improving mental health through neighbourhood regeneration: the role of cohesion, belonging, quality and disorder. Eur J Pub Health 30(5):964–966

Holmes LM, Marcelli EA (2020) Neighborhood social cohesion and serious psychological distress among brazilian immigrants in boston. Community Ment Health J 56(1):149–156

Lt Hu, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55

Huang G, Duan Y, Guo F et al (2020) Prevalence and related influencing factors of depression symptoms among empty-nest older adults in China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 91:104183

Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE et al (2007) Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: a cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse Negl 31(3):231–253

Jencks C, Mayer SE (1990) The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. Inn-city poverty in the United States 111:186

Jiang J, Wang P (2020) Does early peer relationship last long? the enduring influence of early peer relationship on depression in middle and later life. J Affect Disord 273:86–94

Kuh DJ, Wadsworth ME (1993) Physical health status at 36 years in a British national birth cohort. Soc Sci Med 37(7):905–916

Lee J (2011) Pathways from education to depression. J Cross Cult Gerontol 26(2):121–135

Lowe SR, Quinn JW, Richards CA et al (2016) Childhood trauma and neighborhood-level crime interact in predicting adult posttraumatic stress and major depression symptoms. Child Abuse Negl 51:212–222

Lyu J, Burr JA (2015) Socioeconomic status across the life course and cognitive function among older adults: an examination of the latency, pathways, and accumulation hypotheses. J Aging Health 28(1):40–67

McDonough P, Worts D, Booker C et al (2015) Cumulative disadvantage, employment–marriage, and health inequalities among American and British mothers. Advances in Life Course Res 25:49–66

Mead GH (1934) Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

MerskyTopitzesReynolds JPJAJ (2013) Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl 37(11):917–925

Metzler M, Merrick MT, Klevens J et al (2017) Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: shifting the narrative. Child Youth Serv Rev 72:141–149

Meyer OL, Castro-Schilo L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S (2014) Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am J Public Health 104(9):1734–1741

Min J, Ailshire J, Crimmins EM (2016) Social engagement and depressive symptoms: do baseline depression status and type of social activities make a difference? Age Ageing 45(6):838–843

Minh A, Muhajarine N, Janus M et al (2017) A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: how, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health Place 46:155–174

Monnat SM, Chandler RF (2015) Long-term physical health consequences of adverse childhood experiences. Sociol Q 56(4):723–752

Morrissey K, Kinderman P (2020) The impact of childhood socioeconomic status on depression and anxiety in adult life: testing the accumulation, critical period and social mobility hypotheses. SSM Popul Health 11:100576

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2012) Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA

Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P et al (2015) Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: a stress process analysis. Child Abuse Negl 45:143–153

Phillips AC, Carroll D, Der G (2015) Negative life events and symptoms of depression and anxiety: stress causation and/or stress generation. Anxiety Stress Coping 28(4):357–371

Runsten S, Korkeila K, Koskenvuo M et al (2014) Can social support alleviate inflammation associated with childhood adversities? Nord J Psychiatry 68(2):137–144

Shuey KM, Willson AE (2008) Cumulative disadvantage and black-white disparities in life-course health trajectories. Res Aging 30(2):200–225

Silk JS, Sessa FM, Morris AS et al (2004) Neighborhood cohesion as a buffer against hostile maternal parenting. J Fam Psychol 18(1):135–146

Vartanian TP, Houser L (2010) The effects of childhood neighborhood conditions on self-reports of adult health. J Health Soc Behav 51(3):291–306

Verropoulou G, Serafetinidou E, Tsimbos C (2021) Decomposing the effects of childhood adversity on later-life depression among Europeans: a comparative analysis by gender. Ageing Soc 41(1):158–186

Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE et al (2006) Childhood adversity and psychosocial adjustment in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(4):307–315

Yang X, Pan A, Gong J et al (2020) Prospective associations between depressive symptoms and cognitive functions in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults. J Affect Disord 263:692–697

Zhang W, Liu S, Zhang K et al (2020) Neighborhood social cohesion, resilience, and psychological well-being among chinese older adults in Hawai’i. Gerontologist 60(2):229–238

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP et al (2014) Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol 43(1):61–68

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY is the sole author of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L. Childhood neighbourhood quality, peer relationships, and trajectory of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02612-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02612-6