Abstract

Purpose

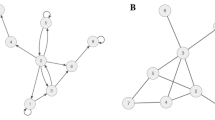

The structure of relationships in a social network affects the suicide risk of the people embedded within it. Although current interventions often modify the social perceptions (e.g., perceived support and sense of belonging) for people at elevated risk, few seek to directly modify the structure of their surrounding social networks. We show social network structure is a worthwhile intervention target in its own right.

Methods

A simple model illustrates the potential of interventions to modify social structure. The effect of these basic structural interventions on suicide risk is simulated and evaluated. Its results are briefly compared to emerging empirical findings for real network interventions.

Results

Even an intentionally simplified intervention on social network structure (i.e., random addition of social connections) is likely to be both effective and safe. Specifically, this illustrative intervention had a high probability of reducing the overall suicide risk, without increasing the risk of those who were healthy at baseline. It also frequently resolved stable, high-risk clusters of people at elevated risk. These illustrative results are generally consistent with emerging evidence from real social network interventions for suicide.

Conclusion

Social network structure is a neglected, but valuable intervention target for suicide prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All codes for creating simulated data and resulting figures are available at osf.io/4vyw9.

Notes

In this discussion, ‘node’ is always equivalent to ‘vertex’ and so the terms are used interchangeably. The same is true for ‘ties’, ‘links’, ‘edges’ and ‘arcs’, which are also used interchangeably. Readers seeking to further their exploration of social networks beyond the current discussion will find these conventions can almost always be safely assumed in other papers too. Exceptions exist, (e.g., ‘arc’ is occasionally reserved for directed relationships, like parent to child), but they are especially uncommon in the recent literature.

Note, it is of course unlikely an real person ‘chooses’ to be at elevated risk for suicide. But when describing this model and its results, we will say that someone ‘adopts a risky state’ or that they ‘adopt a healthy state’ for simplicity.

References

Durkheim E. Suicide. Unknown edition. Free Press Feb-01–1997, 1897

Bearman PS, Moody J (2004) Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am J Public Health 94:89–95

Cero I, Witte TK (2020) Assortativity of suicide-related posting on social media. Am Psychol 75:365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000477

Clark KA, Salway T, McConocha EM, Pachankis JE (2022) How do sexual and gender minority people acquire the capability for suicide? Voices from survivors of near-fatal suicide attempts. SSM - Qual Res Health 2:100044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100044

Pescosolido BA, Georgianna S (1989) Durkheim, suicide, and religion: toward a network theory of suicide. Am Sociol Rev 54:33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095660

Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Haro JM (2015) The association of relationship quality and social networks with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among older married adults: Findings from a cross-sectional analysis of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J Affect Disord 179:134–141

Wyman PA, Pickering TA, Pisani AR, Rulison K, Schmeelk-Cone K, Hartley C et al (2019) Peer-adult network structure and suicide attempts in 38 high schools: implications for network-informed suicide prevention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 60:1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13102

Xiao Y, Lindsey MA (2022) Adolescent social networks matter for suicidal trajectories: disparities across race/ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, and socioeconomic status. Psychol Med 52:3677–3688

Joiner TE (2003) Contagion of suicidal symptoms as a function of assortative relating and shared relationship stress in college roommates. J Adolesc 26:495–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00133-1

King CA, Arango A, Kramer A, Busby D, Czyz E, Foster CE et al (2019) Association of the youth-nominated support team intervention for suicidal adolescents with 11-to 14-year mortality outcomes: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat 76:492–498

Calear AL, Brewer JL, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon A, Wyman PA, LoMurray M et al (2016) The sources of strength Australia Project: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 17:349. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1475-1

King CA, Klaus N, Kramer A, Venkataraman S, Quinlan P, Gillespie B (2009) The youth-nominated support team-version II for suicidal adolescents: a randomized controlled intervention trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 77:880–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016552

Wyman PA, Brown CH, LoMurray M, Schmeelk-Cone K, Petrova M, Yu Q et al (2010) An outcome evaluation of the sources of strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. Am J Public Health 100:1653–1661. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.190025

Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD et al (2015) Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiat 72:475–482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

Stanley B, Brown GK (2012) Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract 19:256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001

Newman M, Park J (2000) Why social networks are different from other types of networks. Phys Rev E 68:036122. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.036122

Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2013) Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat Med 32:556–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5408

Barabasi A (2002) Linked: the new science of networks, 1st edn. Perseus Books Group, Cambridge, Mass

Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2011) Connected: the surprising power of our social networks and how they shape our lives, Reprint. Back Bay Books, New York

Crossley N, Bellotti E, Edwards G, Everett MG, Koskinen J, Tranmer M (2015) Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets, 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP. SAGE Publications Ltd

Knoke D, Yang S (2007) Social Network Analysis, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications Inc

Newman M. Networks (2018) Oxford University Press

Wasserman S, Faust K (1994) Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, UK

Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, Oasi O, Olié E, Carvalho AF et al (2019) Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: a narrative review of the literature. J Affect Disord 245:653–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022

Haw C, Hawton K, Niedzwiedz C, Platt S (2013) Suicide clusters: a review of risk factors and mechanisms. Suicide Life Threat Behav 43:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00130.x

Heuser C, Howe J (2018) The relation between social isolation and increasing suicide rates in the elderly. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 20(1):2–9

Zamora-Kapoor A, Nelson LA, Barbosa-Leiker C, Comtois KA, Walker LR, Buchwald DS (2016) Suicidal ideation in American Indian/Alaska Native and White adolescents: the role of social isolation, exposure to suicide, and overweight. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 23:86–100

Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR et al (2017) The interpersonal theory of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol Bull 143:1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N et al (2020) Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States 2019. MMWR Suppl 69:47–55. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2018 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. 2020.

Girard JM, Cohn JF, Mahoor MH, Mavadati SM, Hammal Z, Rosenwald DP (2014) Nonverbal social withdrawal in depression: Evidence from manual and automatic analyses. Image Vis Comput 32:641–647

Spirito A, Overholser J, Stark LJ (1989) Common problems and coping strategies II: findings with adolescent suicide attempters. J Abnorm Child Psychol 17:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913795

Edmonds B, Le Page C, Bithell M, Chattoe-Brown E, Grimm V, Meyer R et al (2019) Different modelling purposes. J Artif Soc Soc Simul 22:6

Epstein JM (2008) Why model? J Artif Soc Soc Simul 11:12

Wyman PA, Pisani AR, Brown CH et al (2020) Effect of Wingman-connect upstream suicide prevention for air force personnel in training: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2022532. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22532

Wyman PA, Pickering TA, Pisani AR, Cero I, Yates B, Schmeelk-Cone K et al (2022) Wingman-connect program increases social integration for air force personnel at elevated suicide risk: social network analysis of a cluster RCT. Soc Sci Med 296:114737

Newcomer AR, Roth KB, Kellam SG, Wang W, Ialongo NS, Hart SR et al (2016) Higher childhood peer reports of social preference mediates the impact of the good behavior game on suicide attempt. Prev Sci 17:145–156

Wilcox HC, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS, Wang W et al (2008) The impact of two universal randomized first- and second-grade classroom interventions on young adult suicide ideation and attempts. Drug Alcohol Depend 95(Supplement 1):S60-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.005

Cero I (2021) Network health intervention for adolescents hospitalized for suicide attempts

Turner JC, Brown RJ, Tajfel H (1979) Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur J Soc Psychol 9:187–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420090207

Brown R (2020) The origins of the minimal group paradigm. Hist Psychol 23:371

Aron A, Melinat E, Aron EN, Vallone RD, Bator RJ (1997) The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: a procedure and some preliminary findings. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 23:363–377

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant (KL2 TR001999) from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It was also supported by a National Institutes of Health Extramural Loan Repayment Award for Clinical Research (L30 MH120727).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IC and PW conceived of the idea and wrote a majority of the manuscript. MDC also contributed to the writing process. IC prepared all figures and analysis code. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Ethical approval

No human subjects’ research was conducted.

Patient consent

No human subjects’ research was conducted.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cero, I., De Choudhury, M. & Wyman, P.A. Social network structure as a suicide prevention target. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 59, 555–564 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02521-0