Abstract

Background

Mental health disorders have an increased prevalence in communities that experienced devastating natural disasters. Maria, a category 5 hurricane, struck Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, weakening the island’s power grid, destroying buildings and homes, and limiting access to water, food, and health care services. This study characterized sociodemographic and behavioral variables and their association with mental health outcomes in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

Methods

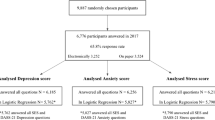

A sample of 998 Puerto Ricans affected by Hurricane Maria was surveyed between December 2017 and September 2018. Participants completed a 5-tool questionnaire: Post-Hurricane Distress Scale, Kessler K6, Patient Health Questionnaire 9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) 7, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder checklist for DSM-V. The associations of sociodemographic variables and risk factors with mental health disorder risk outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Most respondents reported experiencing hurricane-related stressors. Urban respondents reported a higher incidence of exposure to stressors when compared to rural respondents. Low income (OR = 3.66; 95% CI = 1.34–11.400; p < 0.05) and level of education (OR = 4.38; 95% CI = 1.20–15.800; p < 0.05) were associated with increased risk for severe mental illness (SMI), while being employed was correlated with lower risk for GAD (OR = 0.48; 95% CI = 0.275–0.811; p < 0.01) and lower risk for SIM (OR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.483–0.952; p < 0.05). Abuse of prescribed narcotics was associated with an increased risk for depression (OR = 2.94; 95% CI = 1.101–7.721; p < 0.05), while illicit drug use was associated with increased risk for GAD (OR = 6.56; 95% CI = 1.414–39.54; p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Findings underline the necessity for implementing a post-natural disaster response plan to address mental health with community-based social interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the Mendeley Data, http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/9rhgdh3cdn.1.

References

Schwartz RM et al (2015) The impact of Hurricane Sandy on the mental health of New York area residents. Am J Disaster Med 10(4):339–346

Sirey JA et al (2017) Storm impact and depression among older adults living in Hurricane Sandy-affected areas. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 11(1):97–109

Cao X et al (2015) Psychological distress and health-related quality of life in relocated and nonrelocated older survivors after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Asian Nurs Res 9(4):271–277

Galea S et al (2007) Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(12):1427–1434

Gros DF et al (2012) Relations between loss of services and psychiatric symptoms in urban and non-urban settings following a natural disaster. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 34(3):343–350

van Griensven F et al (2006) Mental health problems among adults in tsunami-affected areas in southern Thailand. JAMA 296(5):537–548

Kessler RC et al (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(12):1048–1060

Casey JA et al (2021) Trends from 2008 to 2018 in electricity-dependent durable medical equipment rentals and sociodemographic disparities. Epidemiology 32(3):327–335

Dominianni C et al (2018) Power outage preparedness and concern among vulnerable New York City residents. J Urban Health 95(5):716–726

Montazeri A et al (2005) Psychological distress among Bam earthquake survivors in Iran: a population-based study. BMC Public Health 5:4

Caldera T et al (2001) Psychological impact of the hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua in a one-year perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36(3):108–114

Schwartz RM et al (2016) The lasting mental health effects of Hurricane Sandy on residents of the Rockaways. J Emerg Manag 14(4):269–279

Mills J et al (2013) Sex and drug risk behavior pre- and post-emigration among Latino migrant men in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. J Immigr Minor Health 15(3):606–613

Niitsu T et al (2014) The psychological impact of a dual-disaster caused by earthquakes and radioactive contamination in Ichinoseki after the Great East Japan Earthquake. BMC Res Notes 7:307

Brown BJ (1990) Leadership and followership. Tex Nurs 64(9):13

Fothergill AP (2004) Lori poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Nat Hazards 32:89–110

Sebastián M, William AG, Olga M (2007) Land development, land use, and urban sprawl in Puerto Rico integrating remote sensing and population census data. Landsc Urban Plan 79(3):288–297

Martinuzzi S, et al. (2008) Urban and rural land use in Puerto Rico. 2008: Res. Map IITF-RMAP-01. Rio Piedras, PR: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry.

Carl Y et al (2019) Post-Hurricane Distress Scale (PHDS): a novel tool for first responders and disaster researchers. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 13(1):82–89

Carl Y et al (2020) The correlation of English language proficiency and indices of stress and anxiety in migrants from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria: a preliminary study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 14(1):23–27

Chastang F et al (1998) Suicide attempts and job insecurity: a complex association. Eur Psychiatry 13(7):359–364

Fullerton CS et al (2015) Depressive symptom severity and community collective efficacy following the 2004 Florida Hurricanes. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0130863

Libby AM et al (2012) Economic differences in direct and indirect costs between people with epilepsy and without epilepsy. Med Care 50(11):928–933

Ranasinghe S, Ramesh S, Jacobsen KH (2016) Hygiene and mental health among middle school students in India and 11 other countries. J Infect Public Health 9(4):429–435

Spitzer RL et al (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097

Prochaska JJ et al (2012) Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 21(2):88–97

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613

Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D (2012) Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 184(3):E191–E196

Blevins CA et al (2015) The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 28(6):489–498

Kim G et al (2016) Measurement equivalence of the K6 Scale: the effects of race/ethnicity and language. Assessment 23(6):758–768

Miles JN, Marshall GN, Schell TL (2008) Spanish and English versions of the PTSD checklist-civilian version (PCL-C): testing for differential item functioning. J Trauma Stress 21(4):369–376

Munoz-Navarro R et al (2017) Utility of the PHQ-9 to identify major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care centres. BMC Psychiatry 17(1):291

Carl Y et al (2022) Post-Hurricane Distress Scale (PHDS): determination of general and disorder-specific cutoff scores. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(9):5204

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX (2013) Applied logistic regression. Third edition Wiley series in probability and statistics, vol xvi. Wiley, Hoboken New Jersey, p 500

Beatty T, Shimshack J, Volpe R (2019) Disaster preparedness and disaster response: evidence from sales of emergency supplies before and after Hurricanes. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 6(4):633–668

Casey JA et al (2020) Power outages and community health: a narrative review. Curr Environ Health Rep 7(4):371–383

Chakalian PM, Kurtz LC, Hondula DM (2019) After the lights go out: household resilience to electrical grid failure following Hurricane Irma. Nat Hazard Rev. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000335

Yabe T, Rao PSC, Ukkusuri SV (2021) Regional differences in resilience of social and physical systems: case study of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci 48(5):1042–1057

Mulhere K (2018) Here’s the one place in America where the gender pay gap is reversed, in Money.

Caraballo-Cueto J, Segarra-AlmÉStica E (2019) Do gender disparities exist despite a negative gender earnings gap? Economía 19(2):101–126

Ficek RE (2018) Infrastructure and colonial difference in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María. Transform Anthropol 26(2):102–117

Respaut R, Graham D (2017) Desperate travelers crowd Puerto Rico airport in hopes of seat out, in Reuters.

Santiago ALH (2019) Puerto Rican evacuees are still in New York, still struggling, in City & State New York.

Vargas C (2018) Puerto Rican hurricane evacuees in Philadelphia: 'No help at all', in The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Elliott JR, Pais J (2010) When nature pushes back: environmental impact and the spatial redistribution of socially vulnerable populations. Soc Sci Q 91(5):1187–1202

Ash KD, Cutter SL, Emrich CT (2013) Acceptable losses? The relative impacts of natural hazards in the United States, 1980–2009. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 5:61–72

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Andrea Lopez-Cepero and Dr. Raymond Tremblay for statistical and research guidance. Additionally, we thank Dr. Estela Estapé and Dr. Martha García for the project design and review guidelines. We thank Sara Kurtevski, Melissa Milian-Rodriguez, Anamaris Torres-Sanchez, and Melissa Matos-Rivera, who helped in the recruitment of participants. The research was supported by the American Psychiatric Association Helping Hands Grant–2018_SJB_01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All co-authors have both contributed substantially and approved this manuscript before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The San Juan Bautista School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Approval num. SJBSM IRB# 22-2018) reviewed and approved the administration protocol. All participants were 18 years old or older and provided written informed consent for participate in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to publication

We can attest that this paper is neither presently under consideration at another publication nor will be while it is under consideration by Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stukova, M., Cardona, G., Tormos, A. et al. Mental health and associated risk factors of Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane María. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 1055–1063 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02458-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02458-4