Abstract

Purpose

High-frequency cannabis use in adolescents has been associated with adult mental illness. In contrast, physical activity has been demonstrated to benefit mental health status. The purpose of this study was to examine whether, within a 1-year prospective study design, changes in cannabis use frequency are associated with changes in mental health, and whether meeting physical activity guidelines moderates these associations.

Methods

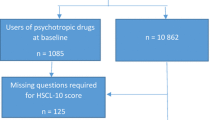

COMPASS (2012–2021) is a hierarchical longitudinal health data survey from a rolling cohort of secondary school students across Canada; student-level mental health data linked from Years 5 (2016/17) and 6 (2017/18) were analysed (n = 3173, 12 schools). Multilevel conditional change regression models were used to assess associations between mental health scores change, cannabis use change and physical activity guideline adherence change after adjusting for covariates.

Results

Adopting at least weekly cannabis use was associated with increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms and decreases in psychosocial well-being. Maintaining physical activity guidelines across both years improved psychosocial well-being regardless of cannabis use frequency, and offset increases in depressive symptoms among individuals who adopted high frequency cannabis use. Physical activity adherence had no apparent relationship with anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion

Regardless of the sequence of events, adopting high frequency cannabis use may be a useful behavioural marker of current or future emotional distress, and the need for interventions to address mental health. Physical activity adherence may be one approach to minimizing potential changes in mental health associated with increasing cannabis use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rotermann M, Langlois K (2015) Prevalence and correlates of marijuana use in Canada, 2012. Heal Reports 26:10–15

Kelsall D (2017) Cannabis legislation fails to protect Canada’s youth. Can Med Assoc J 189:E737–E738. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170555

Grant CN, Bélanger RE (2017) Cannabis and Canada’s children and youth. Paediatr Child Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx017

Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A et al (2007) Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3

Radhakrishnan R, Wilkinson ST, D’Souza DC (2014) Gone to pot-a review of the association between cannabis and psychosis. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00054

Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT et al (2011) Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5

Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F et al (2014) Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt181

Porath-Waller AJ, Beasley E, Beirness DJ (2010) A meta-analytic review of school-based prevention for cannabis use. Heal Educ Behav 37:709–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198110361315

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2018) Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study (2017) (GBD 2017) Results. Inst Heal Metrics Eval, Seattle

Skinner H, Biscope S, Poland B, Goldberg E (2003) How adolescents use technology for health information: implications for health professionals from focus group studies. J Med Internet Res 5:e32. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5.4.e32

Gobbi G, Atkin T, Zytynski T et al (2019) Association of Cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76:426–434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500

McDonald AJ, Roerecke M, Mann RE (2019) Adolescent cannabis use and risk of mental health problems—the need for newer data. Addiction 114:1889–1890. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14724

Lawless L, Drichoutis AC, Nayga RM (2013) Time preferences and health behaviour: a review. Agric Food Econ 1:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-7532-1-17

Unterrainer JM, Domschke K, Rahm B et al (2018) Subclinical levels of anxiety but not depression are associated with planning performance in a large population-based sample. Psychol Med 48:168–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002562

Haller H, Cramer H, Lauche R et al (2014) The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 14:128. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-128

Martin JK, Blum TC, Beach SRH, Roman PM (1996) Subclinical depression and performance at work. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00789116

Beck A, Lauren Crain A, Solberg LI et al (2011) Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. Ann Fam Med 9:305–311. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1260

World Health Organization (2020) Basic documents: forty-ninth edition (including amendments adopted up to 31 May 2019). Geneva. ISBN 978-92-4-000051-3. https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/

Westerhof GJ, Keyes CLM (2010) Mental illness and mental health: the two continua model across the lifespan. J Adult Dev 17:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y

Zuckermann AM, Gohari MR, DeGroh M et al (2020) Cannabis cessation among youth: rates, patterns and academic outcomes in a large prospective cohort of Canadian high school students. Heal Promot Chronic Dis Prev Canada 40:95–103. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.40.4.01

Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC et al (2014) Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 1:286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70307-4

Butler A, Patte KA, Ferro MA, Leatherdale ST (2019) Interrelationships among depression, anxiety, flourishing, and cannabis use in youth. Addict Behav 89:206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.007

Romano I, Williams G, Butler A et al (2019) Psychological and behavioural correlates of cannabis use among canadian secondary school students: findings from the COMPASS study. Can J Addict 10:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/CXA.0000000000000058

Whitelaw S, Teuton J, Swift J, Scobie G (2010) The physical activity—mental wellbeing association in young people: A case study in dealing with a complex public health topic using a “realistic evaluation” framework. Ment Health Phys Act 3:61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2010.06.001

Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al (2013) Exercise for depression. In: Mead GE (ed) Cochrane database of systematic reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, CD004366

Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J et al (2016) Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res 77:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023

Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, Carta MG (2014) Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. CNS Spectr 19:496–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852913000953

Tremblay MS, Carson V, Chaput JP et al (2016) Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0151

Leatherdale ST, Brown KS, Carson V et al (2014) The COMPASS study: a longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and built environment resources. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-331

Patte KA, Bredin C, Henderson J et al (2017) Development of a mental health module for the compass system: improving youth mental health trajectories. Part 1: tool development and design. COMPASS Tech Rep Ser 4:1–27. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/development-mental-health-module-compass-system-improving

Patte KA, Bredin C, Henderson J et al (2017) Development of a mental health module for the COMPASS system: Improving youth mental health trajectories Part 2: pilot test and focus group results. COMPASS Tech Rep Ser 4:1–42. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/development-mental-health-module-compass-system-improving-0

Qian W, Battista K, Bredin C et al (2015) Assessing longitudinal data linkage results in the COMPASS study. Compass Tech Rep Ser 3. https://www.uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/publications/assessing-longitudinal-data-linkage-results-compass-study. Accessed 1 May 2020

White VM, Hill DJ, Effendi Y (2004) How does active parental consent influence the findings of drug-use surveys in schools? Eval Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X03259549

Thompson-Haile A, Bredin C, Leatherdale ST (2013) Rationale for using an active-information passive-consent permission protocol in COMPASS. Compass Tech Rep Ser 1:1–10. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/publications/rationale-using-active-information-passive-consent

Reel B, Bredin C, Leatherdale ST (2018) COMPASS year 5 and 6 school recruitment and retention. Compass Tech Rep Ser 5:1–10. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/publications/compass-year-5-and-6-school-recruitment-and-retention

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med 10:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6

Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, Brannen CL (2010) Factorial validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression 10 in adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31:408–412. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903484105

Haroz EE, Ybarra ML, Eaton WW (2014) Psychometric evaluation of a self-report scale to measure adolescent depression: The CESDR-10 in two national adolescent samples in the United States. J Affect Disord 158:154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.009

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK et al (2017) The generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry 29:227–234A

Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S et al (2008) Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 46:266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Diener E, Wirtz D, Biswas-diener R et al (2009) New measures of well-being: flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12

Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W et al (2010) New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Van Laar M, Van Dorsselaer S, Monshouwer K, De Graaf R (2007) Does cannabis use predict the first incidence of mood and anxiety disorders in the adult population? Addiction 102:1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01875.x

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N (2002) Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction 97:1123–1135. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x

Wong SL, Leatherdale ST, Manske S (2006) Reliability and validity of a school-based physical activity questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38:1593–1600. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000227539.58916.35

Aickin M (2009) Dealing with change: using the conditional change model for clinical research. Perm J. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/08-070

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Faraway JJ (2016) Extending the linear model with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker N et al (2009) GLM and GAM for count data. In: Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker N et al (eds) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-87458-6

Campion WM, Rubin DB (1989) Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. J Mark Res. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172772

van Buuren S (2018) Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, Second Edi. CRC Press

Fox J, Weisberg S, Price B, Monette G (2019) carEx: supplemental and experimental functions. https://rdrr.io/rforge/carEx/

Lenth R (2019) emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. https://github.com/rvlenth/emmeans

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57:289–300

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45:1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

Robitzsch A, Grund S, Henke T (2019) miceadds: some additional multiple imputation functions, especially for mice. https://github.com/alexanderrobitzsch/miceadds

Ferro MA (2014) Missing data in longitudinal studies: Cross-sectional multiple imputation provides similar estimates to full-information maximum likelihood. Ann Epidemiol 24:75–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.007

Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD (2007) How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9

Zuckermann AME, Battista K, de Groh M et al (2019) Prelegalisation patterns and trends of cannabis use among Canadian youth: results from the COMPASS prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 9:e026515. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026515

Womack SR, Shaw DS, Weaver CM, Forbes EE (2016) Bidirectional associations between cannabis use and depressive symptoms from adolescence through early adulthood among at-risk young men. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2016.77.287

Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM et al (2018) Self-medication of mood and anxiety disorders with marijuana: Higher in states with medical marijuana laws. Drug Alcohol Depend. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.009

Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S et al (2017) An examination of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for people with anxiety and stress-related disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 249:102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.020

Stonerock GL, Hoffman BM, Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA (2015) Exercise as treatment for anxiety: systematic review and analysis. Ann Behav Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9685-9 (Epub ahead of print)

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT et al (2013) A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

Lubans DR, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans NJ (2012) Review: a systematic review of the impact of physical activity programmes on social and emotional well-being in at-risk youth. Child Adolesc Ment Health 17:2–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00623.x

Austin PC, Steyerberg EW (2015) The number of subjects per variable required in linear regression analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 68:627–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.014

Funding

The COMPASS study has been supported by a bridge grant from the CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD) through the “Obesity—Interventions to Prevent or Treat” priority funding awards (OOP-110788; awarded to SL), an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) (MOP-114875; awarded to SL), a CIHR Project Grant (PJT-148562; awarded to SL), a CIHR bridge grant (PJT-149092; awarded to KP/SL), a CIHR Project Grant (PJT-159693; awarded to KP), and by a research funding arrangement with Health Canada (#1617-HQ-000012; contract awarded to SL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no further competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duncan, M.J., Patte, K.A. & Leatherdale, S.T. Hit the chronic… physical activity: are cannabis associated mental health changes in adolescents attenuated by remaining active?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 141–152 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01900-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01900-1