Abstract

Background

Reports of a meaningful relationship between mental health-related conditions and work productivity measures are relatively common. These, however, are frequently examined for their linearity while ignoring untapped, and potentially rich, non-linear associations.

Methods

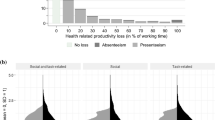

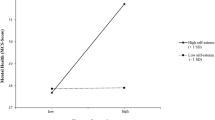

Following a serendipitous finding of a curvilinear relationship between workplace presenteeism (lowered productivity while at work) and depression, an investigation was undertaken of the association between worklife prevalence measures of presenteeism (measured by the W.H.O. Health & Work Performance Questionnaire) and lifetime prevalence of twelve psychosocial vulnerabilities, encompassing mental health, mental health-related, and addictive conditions. Linear and quadratic (U-shaped) functions were calculated across the “relative” presenteeism measure (self vs. other workers) for each of the 12 conditions.

Results

A visual analysis revealed a U-shaped graphic function in all conditions, and excepting anxiety all were statistically significant. In general, increases beyond the lowest (“poorest”) level of self-reported comparative productivity were associated with increases in psychosocial stability, but only as far as deemed equality. Beyond that, increases in self-confidence resulted in a reversal, thus returning to a higher level of vulnerability for the condition in question. A cursory scan of five relevant journals indicated that non-linear analyses were often possible, but rarely carried out.

Conclusions

This has informative value for our conceptualization of overconfidence, and it begs the question of whether an over-reliance on linear measures has caused us to overlook important curvilinear human relationships. The inclusion of analyses of non-linear functions is suggested as a matter of course for future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

The original database and the questionnaire have been provided to researchers and policy makers upon request.

References

Koopman C, Pelletier KR, Murray JF et al (2002) Stanford Presenteeism Scale: health status and employee productivity. J Occup Environ Med 44:14–20

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D (2003) Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 289:3135–3144

Adler DA, McLaughlin TJ, Rogers WH, Chang H, Lapitsky L, Lerner DM (2006) Job performance deficits due to depression. Am J Psychiatry 163:1569–1576

Dewa CS, Thompson AH, Jacobs P (2011) The association of treatment for major depressive episodes and work productivity. Can J Psychiatry 56(12):743–750

Tabachnik N, Crocker J, Alloy LB (1983) Depression, social comparison, and the false-consensus effect. J Pers Soc Psychol 45:688–699

Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sherman DK, Sage RM, McDowell NK (2003) Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological profiles? J Pers Soc Psychol 85:605–615

Kessler R, White LA, Birnbaum H et al (2008) Comparative and interactive effects of depression relative to other health problems on work performance in the workforce of a large employer. J Occup Environ Med 50(7):809–816

Wang PS, Beck A, Berglund P et al (2003) Chronic medical conditions and work performance in the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire calibration surveys. J Occup Environ Med 45:1303–1311

Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H (2004) The clinical and occupational correlates of work productivity loss among employed patients with depression. J Occup Environ Med 46(6 Suppl):S46–S55

Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L et al (2007) The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180

Sanderson K, Andrews G (2006) Common mental disorders in the workforce: recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Can J Psychiatry 51(2):63–75

Esposito E, Wang JL, Williams JVA, Patten SB (2007) Mood and anxiety disorders, the association with presenteeism in employed members of a general population sample. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 16(3):231–237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00002335

Mattke S, Balakrishnan A, Bergamo G, Newberry SJ (2007) A review of methods to measure health-related productivity loss. Am J Manag Care 13(4):211–217

Noben CYG, Evers SMAA, Nijhuis FJ, de Rijk AE (2014) Quality appraisal of generic self-reported instruments measuring health-related productivity changes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 4:115

Ospina MB, Dennett L, Waye A, Jacobs P, Thompson AH (2015) A systematic review of the measurement properties of instruments assessing presenteeism. Am J Manag Care 21(2):e171–e185

Johns G (2012) Presenteeism: a short history and a cautionary tale. In: Houdmont J, Leka S, Sinclair R (eds) Contemporary occupational health psychology: global perspectives on research and practice. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, pp 204–220

Thompson AH, Waye A (2018) Agreement among the productivity components of eight presenteeism tests in a sample of health care workers. Value Health 21(6):650–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.014

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD (1908) The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol 18:159–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503

de Wit LM, van Straten A, van Herten M, Penninx BWJH, Cuijpers P (2009) Depression and body mass index, a u-shaped association. BMC Public Health 9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-14

Carey M, Small H, Yoong SL, Boyes A, Bisquera A, Sanson-Fisher R (2014) Prevalence of comorbid depression and obesity in general practice: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 64(620):e122–e127. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X677482

Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi V, An Y, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB (2013) The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry 70(8):803–811. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.193

Statistics Canada (2010) Canadian Community Health Survey Mental Health and Well-Being: Cycle 1.2. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Wang JL, Patten SB, Currie S, Sareen J, Schmitz N (2012) A population-based longitudinal study on work environmental factors and the risk of major depressive disorder. Am J Epidemiol 176(1):52–59

Thompson AH, Jacobs P, Dewa CS (2011). The Alberta Survey of addictive behaviours and mental health in the workforce. Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton, 2009. https://www.ihe.ca/advanced-search/the-alberta-survey-of-addictive-behaviours-and-mental-health-in-the-workforce-2009

Dewa CS, Thompson AH, Jacobs P (2010) Relationships between job stress and worker perceived responsibilities and job characteristics. Int J Occup Environ Med 2:37–46

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier L, Sheehan KH, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) (1998) The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 59(Suppl 20):22–33

National Population Health Survey [NPHS] (1997) LANDRU, social science database, through the University of Calgary. Statistics Canada, Alberta

Waterhouse P (1992) Substance use and the Alberta workplace: the prevalence and impacts of alcohol and other drugs. Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission, Edmonton

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care, 2nd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

Skinner H (1982) The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 7:363–371

Ferris J, Wynne H (2001) The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report to the Canadian Inter-Provincial Advisory Committee. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, Ottawa

Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck AL et al (2003) The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med 45(2):156–174

Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA et al (2004) Using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J Occup Environ Med 46(Suppl. 6):S23–S37

Kessler RC, Petukhova M, McInnes K, Ustun TB (2007) Letter regarding “Content and scoring rules for the WHO HPQ absenteeism and presenteeism questions”. https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/hpq/info.php

Brown JD (1986) Evaluations of self and others: self-enhancement biases in social judgments. Soc Cognit 4(4):353–376

Alicke MD, Govorun O (2005) The better-than-average effect. In: Alicke MD, Dunning DA, Kruger JL (eds) The self in social judgment. Psychology Press, New York

Pierce JL, Gardner DG (2004) Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: a review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. J Manag 30(5):591–622

Mantel N (1963) Chi-square tests with one degree of freedom; extensions of the Mantel-Haenszel procedure. J Am Stat Assoc 58:690–700

Sergeant ESG (2016) Epitools epidemiological calculators. Ausvet Pty Ltd. https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/trend. Accessed 22 May 2020

Thompson AH, Bland RC (2017) Gender similarities in somatic depression and in DSM depression secondary symptom profiles within the context of severity and bereavement. J Affect Disord 227:770–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.052

Eysenck HJ (1967) The biological basis of personality. Charles C Thomas, Springfield

Geen RG (1984) Preferred stimulation levels in introverts and extraverts: Effects on arousal and performance. J Pers Soc Psychol 46:1303–1312

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW (1985) Personality and individual differences: a natural science approach. Plenum Press, New York

Tops M, Schlinkert C, Tjew-A-Sin M, Samur D, Koole SL (2015) Protective inhibition of self-regulation and motivation: extending a classic Pavlovian principle to social and personality functioning. In: Gendolla GHE, Tops M, Koole SL (eds) Handbook of biobehavioral approaches to self-regulation. Springer, New York, pp 69–85

Pavlov IP (1927) Conditioned reflexes: an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex (translated by G. V. Anrep). Oxford University Press, London

Kleinsmith LJ, Kaplan S (1963) Paired-associate learning as a function of arousal and interpolated interval. J Exp Psychol 65(2):190–193

Storbeck J, Clore GL (2008) Affective arousal as Information: how affective arousal influences judgments, learning, and memory. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 2(5):1824–1843

Thorndike EL (1939) On the fallacy of imputing the correlations found for groups to the individuals or smaller groups composing them. Am J Psychol 52(1):122–124. https://doi.org/10.2307/1416673

Robinson WS (1950) Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Am Sociol Rev 15(3):351–357

Seligman MEP (2006) Learned optimism. Vintage Books (originally published in 1990 by Alfred A. Knopf), New York

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking fast and slow. Doubleday Canada, Vancouver

Kruger J (1999) Lake Wobegon be gone! The "Below-Average Effect" and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol 77(2):221–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.221

Kruger J, Dunning D (1999) Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol 77(6):1121–1134

Grant AM, Schwartz B (2011) Too much of a good thing: the challenge and opportunity of the Inverted U. Perspect Psychol Sci 6(1):61–76

Seligman MEP, Csikszentmilhayi M (2000) Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol 55:5–14

Peterson C, Seligman MEP (2004) Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification. Oxford University Press, New York

Bass BM (1998) Transformational leadership: industry, military, and educational impact. Erlbaum, Malwah

Bono JE, Judge TA (2004) Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 89:901–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.901

House RJ, Howell JM (1992) Personality and charismatic leadership. Leadersh Q 3:81–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(92)90028-E

Dóci E, Hofmans J (2015) Task complexity and transformational leadership: the mediating role of leaders’ state core self-evaluations. Leadersh Q 26:436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.02.008

Deluga RJ (2001) American presidential Machiavellianism: implications for charismatic leadership and rated performance. Leadersh Q 12:339–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00082-0

Popper M (2002) Narcissism and attachment patterns of personalized and socialized charismatic leaders. J Soc Pers Relat 9:797–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502196004

Sankowsky D (1995) The charismatic leader as narcissist: understanding the abuse of power. Organ Dyn 23:57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(95)90017-9

Vergauwe J, Wille B, Hofmans J, Kaiser RB, De Freut P (2018) The double-edged sword of leader charisma: understanding the curvilinear relationship between charismatic personality and leader effectiveness. Pers Process Ind Differ 114(1):110–130

Sapolsky RM (2015) Stress and the brain: individual variability and the inverted-U. Nat Neurosci 18(10):1344–1346

Funding

The study that produced the database in use here was funded by a contract from the Alberta (Canada) Alcohol & Drug Abuse Commission, payable to the Institute of Health Economics (Edmonton, Canada).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest associated with this paper.

Ethics approval

The study that produced the database in use here was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta.

Consent to participate

In the study that produced the database in use here, respondents were interviewed by telephone (random dialing). It was explained that taking the survey is a personal choice, that names will not be taken, that information will be kept confidential and anonymous, that any question can be skipped- or the interview can be stopped at any time without negative consequences, and that the data collected will be stored in a locked site at the Institute of Health Economics and kept for at least 5 years. Furthermore, respondents were offered contact information for (1) mental health services (2) the project director, and (3) Health Research Ethics Board.

No prior publication

This work has not been published before (neither in English nor in any other language) and that it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, A.H. Measures of mental health and addictions conditions show a U-shaped relationship with self-rated worker performance. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 1823–1833 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01894-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01894-w