Abstract

Purpose

Social support is an important correlate of health behaviors and outcomes. Studies suggest that veterans have lower social support than civilians, but interpretation is hindered by methodological limitations. Furthermore, little is known about how sex influences veteran–civilian differences. Therefore, we examined veteran–civilian differences in several dimensions of social support and whether differences varied by sex.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III, a nationally representative sample of 34,331 respondents (male veterans = 2569; female veterans = 356). We examined veteran–civilian differences in functional and structural social support using linear regression and variation by sex with interactions. We adjusted for socio-demographics, childhood experiences, and physical and mental health.

Results

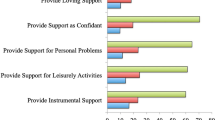

Compared to civilians, veterans had lower social network diversity scores (difference [diff] = − 0.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 0.23, − 0.03). Among women but not men, veterans had smaller social network size (diff = − 2.27, 95% CI − 3.81, − 0.73) than civilians, attributable to differences in religious groups, volunteers, and coworkers. Among men, veterans had lower social network diversity scores than civilians (diff = − 0.13, 95% CI − 0.23, − 0.03); while among women, the difference was similar but did not reach statistical significance (diff = − 0.13, 95% CI − 0.23, 0.09). There was limited evidence of functional social support differences.

Conclusion

After accounting for factors that influence military entry and social support, veterans reported significantly lower structural social support, which may be attributable to reintegration challenges and geographic mobility. Findings suggest that veterans could benefit from programs to enhance structural social support and improve health outcomes, with female veterans potentially in greatest need.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7:e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Lindsay Smith G, Banting L, Eime R et al (2017) The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0509-8

Gallant MP (2003) The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav 30:170–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198102251030

Cohen S (1997) Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 277:1940. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540480040036

Wang H-X, Mittleman MA, Orth-Gomer K (2005) Influence of social support on progression of coronary artery disease in women. Soc Sci Med 60:599–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.021

Leavy RL (1983) Social support and psychological disorder: a review. J Community Psychol 11:3–21

Kleiman EM, Liu RT (2013) Social support as a protective factor in suicide: findings from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord 150:540–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.033

Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM (1985) Measuring the Functional Components of Social Support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR (eds) Social support: theory, research and applications. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 73–94

Antonucci TC, Akiyama H (1987) Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. J Gerontol 42:519–527

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/. Accessed 30 Jan 2019

Hoerster KD, Lehavot K, Simpson T et al (2012) Health and Health Behavior Differences. Am J Prev Med 43:483–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.029

Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Nelson KM et al (2012) Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women. Am J Prev Med 42:473–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006

Elnitsky CA, Blevins CL, Fisher MP, Magruder K (2017) Military service member and veteran reintegration: a critical review and adapted ecological model. Am J Orthopsychiatry 87:114–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000244

Nagy E, Moore S (2017) Social interventions: an effective approach to reduce adult depression? J Affect Disord 218:131–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.043

Siette J, Cassidy M, Priebe S (2017) Effectiveness of befriending interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7:e014304. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014304

Vorderstrasse A, Lewinski A, Melkus GD, Johnson C (2016) Social support for diabetes self-management via eHealth interventions. Curr Diab Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-016-0756-0

Angel CM, Woldetsadik MA, Armstrong NJ et al (2020) The Enriched Life Scale (ELS): Development, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity for US military veteran and civilian samples. Transl Behav Med 10:278–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby109

Kobau R, Bann C, Lewis M et al (2013) Mental, social, and physical well-being in New Hampshire, Oregon, and Washington, 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: implications for public health research and practice related to Healthy People 2020 foundation health measures on well-being. Popul Health Metr 11:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-11-19

Fisher GG, Matthews RA, Gibbons AM (2016) Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. J Occup Health Psychol 21:3–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039139

Jordan BK, Schlenger WE, Hough R et al (1991) Lifetime and current prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among vietnam veterans and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:207–215. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270019002

Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM (2000) Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker?: a comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med 160:3252–3257. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

Blosnich JR, Dichter ME, Cerulli C et al (2014) Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA Psychiatry 71:1041. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.724

Katon JG, Lehavot K, Simpson TL et al (2015) Adverse childhood experiences, military service, and adult health. Am J Prev Med 49:573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.020

Bareis N, Mezuk B (2016) The relationship between childhood poverty, military service, and later life depression among men: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. J Affect Disord 206:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.018

Antonucci TC, Akiyama H (1987) An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles 17:737–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287685

Frayne SM, Parker VA, Christiansen CL et al (2006) Health status among 28,000 women veterans: the VA women’s health program evaluation project. J Gen Intern Med 21:S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00373.x

Grant BF, Amsbary M, Chu A et al (2014) Source and accuracy statement: national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III (NESARC-III). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NESARC_Final_Report_FINAL_1_8_15.pdf. Accessed 06 Dec 2019

Cohen S (2004) Social relationships and health. Am Psychol 59:676–684

Merz EL, Roesch SC, Malcarne VL et al (2014) Validation of Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12) scores among English- and Spanish-Speaking Hispanics/Latinos from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol Assess 26:384–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035248

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M et al (2003) Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 111:564–572. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.3.564

Ross J, Waterhouse-Bradley B, Contractor AA, Armour C (2018) Typologies of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship to incarceration in U.S. military veterans. Child Abuse Negl 79:74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.023

Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Eslinger JG, Zimmerman L et al (2016) Adverse childhood experiences, support, and the perception of ability to work in adults with disability. PLoS ONE 11:e0157726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157726

Nurius PS, Fleming CM, Brindle E (2019) Life course pathways from adverse childhood experiences to adult physical health: a structural equation model. J Aging Health 31:211–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317726448

Hughes K (2017) The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2:e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Pearl J (1995) Causal diagrams for empirical research. Biometrika 82:669–688. https://doi.org/10.2307/2337329

Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS et al (2016) Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int J Epidemiol 45:1887–1894. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw341

Patulny R, Siminski P, Mendolia S (2015) The front line of social capital creation—a natural experiment in symbolic interaction. Soc Sci Med 125:8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.026

Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M et al (2009) A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process 72:238–255. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238

Han SC, Castro F, Lee LO et al (2014) Military unit support, postdeployment social support, and PTSD symptoms among active duty and National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Anxiety Disord 28:446–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.004

Sandstrom GM, Dunn EW (2014) Social interactions and well-being: the surprising power of weak ties. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 40:910–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214529799

Lehavot K, Litz B, Millard SP et al (2017) Study adaptation, design, and methods of a web-based PTSD intervention for women Veterans. Contemp Clin Trials 53:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2016.12.002

Drebing CE, Reilly E, Henze KT et al (2018) Using peer support groups to enhance community integration of veterans in transition. Psychol Serv 15:135–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000178

Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD (2010) Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 153:507. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00007

Eisen SV, Schultz MR, Mueller LN et al (2012) Outcome of a randomized study of a mental health peer education and support group in the VA. Psychiatr Serv 63:1243–1246. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100348

Fischer EP, Sherman MD, Han X, Owen RR (2013) Outcomes of participation in the REACH multifamily group program for veterans with PTSD and their families. Prof Psychol Res Pract 44:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032024

Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA (2017) Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol 72:517–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000103

National Association of Community Health Centers (2019) Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences: About the PRAPARE Assessment Tool. In: Protoc. Responding Assess. Patients Assets Risks Exp. https://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/about-the-prapare-assessment-tool/. Accessed 9 Sept 2019

Mota NP, Tsai J, Sareen J et al (2016) High burden of subthreshold DSM-5 post-traumatic stress disorder in U.S. military veterans. World Psychiatry 15:185–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20313

Jakupcak M, Hoerster KD, Varra A et al (2011) Hopelessness and suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans reporting subthreshold and threshold posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 199:272–275

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics (2017) Women Veterans Report: The Past, Present, and Future of Women Veterans. Department of Veterans Affairs

Althouse AD (2016) Adjust for Multiple Comparisons? It’s Not That Simple. Ann Thorac Surg 101:1644–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024

Meffert BN, Morabito DM, Sawicki DA et al (2019) US veterans who do and do not utilize veterans affairs health care services: demographic, military, medical, and psychosocial characteristics. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.18m02350

Griffith J (2010) Citizens coping as soldiers: a review of deployment stress symptoms among reservists. Mil Psychol 22:176–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995601003638967

Elovainio M, Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L et al (2017) Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality in isolated and lonely individuals: an analysis of data from the UK Biobank cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2:e260–e266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30075-0

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME (2006) Social isolation in america: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am Sociol Rev 71:353–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100301

Sachs JD, Layard R, Helliwell JF (2018) World Happiness Report 2018. Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York. https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2018/WHR_web.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan 2020

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gray and Dr. Hoerster were supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Program (CDAs 16–154 and 12–263). Dr. Campbell was supported by VA Office of Academic Affiliations’ Advanced Fellowship in Health Services Research and Development (TPH 61–000-23). Dr. Fortney was supported by a VA Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 17–153). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This was a secondary data analysis and does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, S.B., Gray, K.E., Hoerster, K.D. et al. Differences in functional and structural social support among female and male veterans and civilians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 375–386 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01862-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01862-4