Abstract

Background

A core component of treatment provided by early intervention for psychosis (EI) services is ensuring individuals remain successfully engaged with the service. This ensures they can receive the care they may need at this critical early stage of illness. Unfortunately, rates of disengagement are high in individuals with a first episode of psychosis (FEP), representing a major barrier to effective treatment. This study aimed to ascertain the rates and determinants of disengagement and subsequent re-engagement of young people with FEP in a well-established EI service in Melbourne, Australia.

Method

This cohort study involved all young people, aged 15–24, who presented to the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) service with FEP between 1st January 2011 and 1st September 2014. Data were collected retrospectively from clinical files and electronic records. Cox regression analysis was used to identify determinants of disengagement and re-engagement.

Results

A total of 707 young people presented with FEP during the study period, of which complete data were available for 700. Over half of the cohort (56.3%, N = 394) disengaged at least once during their treatment period, however, the majority of these individuals (85.5%, N = 337) subsequently re-engaged following the initial episode of disengagement. Of those who disengaged from the service, 54 never re-engaged, representing 7.6% of the total cohort. Not being in employment, education or training, not having a family history of psychosis in second degree relatives and using cannabis were found to be significant predictors of disengagement. No significant predictors of re-engagement were identified.

Conclusion

In this study, the rate of disengagement in young people with first-episode psychosis was higher than found previously. Encouragingly, rates of re-engagement were also high. The concept of disengagement from services might be more complex than previously thought with individuals disengaging and re-engaging a number of times during their episode of care. What prompts individuals to re-engage with services needs to be better understood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early intervention in psychosis (EI) services were introduced more than 20 years ago based on the evidence that a longer duration of untreated psychosis is associated with poorer clinical and functional outcomes [1,2,3,4]. In addition, intervention at an early phase of psychosis determines the long-term course of illness [5], with a number of studies showing EI services to be clinically and cost-effective at managing the critical early stage of psychosis [6,7,8,9]. It has been proposed that the success of EI services is in part due to their emphasis on establishing and maintaining an individual’s engagement with the service [10]. This is supported by a number of studies that showed disengagement from EI services being associated with poor treatment outcomes including increased risk of relapse, persistent psychotic symptoms and poorer prognosis [11, 12]. Nevertheless, despite these known benefits of staying engaged with services, the rates of disengagement from EI services are constantly around a third (33%), with a range from 13 to 40% [12,13,14]. The terms ‘engagement’ and ‘disengagement’ have typically been inconsistently defined in the literature [12]. One study referred to disengagement as the ‘termination of treatment despite therapeutic need’ [15], whilst another classified it as occurring when “case notes suggested that patients actively refused any contact with the treatment facility or were not traceable” [16]. We consider the term ‘engaged’ to refer to an individual’s willingness to actively take part in the treatment they have been recommended by a service.

Findings from previous studies suggest there are a number of demographic and clinical factors associated with disengagement in FEP, including substance use [15,16,17,18,19], lack of family support during treatment [16, 18,19,20,21], low severity of illness at baseline [16, 18, 19], past forensic history [16], duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) [15, 19, 21, 22] and unemployment [11, 21]. However, these findings have been inconsistent; for example, substance abuse has been found to be not associated with disengagement in some settings [23]. A major factor that has been neglected in the literature is the rates and determinants of re-engagement in those individuals who have disengaged. Only one study appears to have considered this phenomenon, finding that a small proportion (4.3%) re-engaged through hospitalization and a further 13.4% re-engaged after receiving reminders from clinical staff [24].

Considering the high rates of disengagement amongst this clinical population and the known association with poorer outcomes, identifying the rates and determinants of re-engagement is of critical clinical importance, yet it has been neglected to date in the scientific literature. Furthermore, with the roll out of early intervention for psychosis services across Australia and their increasing popularity globally, knowledge on re-engagement could inform clinical services about how to provide the indicated treatments across the different phases of recovery for individuals affected by a psychotic disorder. This study aimed to determine: (1) the proportion of young people with FEP who disengage from the clinical service, (2) demographic and clinical determinants of disengagement, (3) the proportion of those who have disengaged and subsequently re-engage with the service, and (4) demographic and clinical determinants of re-engagement, including whether re-engagement was associated with hospital admission.

Methods

Setting

Orygen Youth Health (OYH) is a specialist mental health service based in the North-Western area of Melbourne, Australia, for young people aged between 15 and 24. The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) service within OYH provides care to approximately 400 young people with FEP each year from a geographically defined catchment area of over 1 million residents. Sources of referral include local mental health services, general practitioners, law enforcement agencies, community support services, family members and friends, and self-referral. Clients can attend OYH for a maximum of 2 years, except if they are aged less than 16 at the time of referral as in these situations, clients can attend until they reach the age of 18 years. The discharge destination of clients will depend upon their individual needs, but is usually to general practitioners, private psychologists or psychiatrists or public adult mental health services.

Whilst under the care of EPPIC, young people in the acute phase of illness should be seen by a clinician (generally their case manager) between one and three times a week, with at least one of these occurring face-to-face, in early recovery this can drop to weekly contact, and in mid-to-late recovery fortnightly to monthly. They should also be seen by the treating doctor within 7–10 days of commencing psychotropic medication and thereafter every 2–6 weeks, as indicated. The role of the case manager is to coordinate the treatment and care of the young person throughout the episode of care. Treatment should provide support, address acute symptoms and aim to prevent relapse for clients and their family/carers. It can include psychoeducation and developing a Wellness Plan. This plan should outline support needed to access accommodation, vocational, recreational, welfare, and primary health services. In addition to case management, clients may access the following interventions; psychological therapy, family/carer work, medication, physical health interventions, and psychosocial recovery group programs.

Participants

The current study includes individuals who first attended the EPPIC service between 1st January 2011 and 1st September 2014 experiencing a first episode of a psychotic disorder, according to DSM-IV criteria. This includes diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, substance-induced psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, brief psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria to the EPPIC service were (1) diagnosis of FEP according to DSM-IV, (2) aged between 15 and 24 years at the time of presentation; and (3) residence within the North-Western catchment area of Melbourne at the time of presentation. Individuals with comorbid substance misuse or dependence, comorbid personality disorders, and intellectual disability were included. Individuals meeting inclusion criteria can receive treatment from EPPIC for up to 24 months.

Design and procedure

This is a naturalistic cohort study in which the data were recorded prospectively but collected retrospectively from clinical files. Demographic and clinical data were extracted from clients’ paper files and electronic medical records using a specifically designed audit tool. The data form part of a larger dataset in which treating clinicians were responsible for collecting original data with eight researchers transferring these data to the study database.

Instruments, measures and sources of information

Each client file contains information compiled during the treatment period from various sources including initial assessment reports, outpatient notes, inpatient notes (if applicable), clinical review meetings and discharge letters. Clinical information such as diagnosis at 3 months and discharge, any hospital admissions, type and number of antipsychotic medications prescribed, as well as episodes of exacerbation and relapses were recorded. Diagnoses were determined by the treating consultant psychiatrist.

Determinants of disengagement and re-engagement

A number of socio-demographic and clinical factors previously associated with disengagement from EI services were collected. This included age, gender, marital status, employment/education/training status (those who are ‘not in education, employment or training’ are identified as ‘NEET’), duration of untreated psychosis, family history of psychosis (first and second degree relative), type of psychotic disorder (non-affective vs. affective), comorbid substance abuse, alcohol, amphetamine, and cannabis use. We chose to investigate these specific factors based on their availability on electronic medical records.

Disengagement/re-engagement

The definition of disengagement used here was consistent with that used by Conus et al. [16]; that is, participants who “actively refused any contact with the treatment facility or were non-traceable”. This definition of disengagement does not include a set length of time that an individual needs to be non-contactable for to be considered disengaged. Rather that it is declared so by the treating team. We did not consider individuals to have disengaged if they moved out of area and if they informed the clinical team of their move. In these circumstances, the clinical team would then refer the young person to an appropriate service in their new area of residence. If a young person ceased all contact with the clinical team and moved out of area but did not inform them of the move, they would have been classified as having disengaged. As part of EPPIC’s routine processes, case managers and clinicians make extensive efforts to re-engage patients by repeated phone calls, letters to the young person and their families, as well as home visits throughout the entire intended treatment period. The date of disengagement was considered to be the date of last face-to-face contact with case manager.

Re-engagement was said to occur when an individual made face-to-face contact with clinical staff following an episode of disengagement. The date of re-engagement was considered to be the first face-to-face contact with case manager following an episode of disengagement. If the patient was discharged before re-engaging to the service, the discharge date was recorded as an end-point of disengagement. If a young person re-engaged with the EI service following an admission to hospital inpatient ward, this was recorded as the ‘mode of re-entry’ allowing us to explore whether re-engagement was associated with hospital admission.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample; for parametric data, the mean and standard deviation are presented and for non-parametric data, the median and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) are presented. Next, we investigated demographic and clinical predictors of disengagement and re-engagement using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis. For disengagement, time to event was defined as the number of days from first contact recorded with services until disengagement from services. For re-engagement, time to event was defined as the number of days from the date of disengagement to the first date of re-engagement (i.e., when the young person was next seen by the treating team). In the analysis examining predictors of re-engagement, the group who never re-engaged following the first episode of disengagement were examined. The rationale for this method is that individuals who did not re-engage after the 2nd episode of disengaged, had previously re-engaged after the 1st episode and hence it would not be representative to label this group not to have re-engaged. This analysis was used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs (aHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for predictors of disengagement and re-engagement, as it is a time dependent variable. A HR of 1 indicates the same relative risk of disengagement/re-engagement compared to the reference group (did not disengage/did not re-engage); an HR < 1 indicates lower relative risk, and an HR > 1 indicates higher relative risk. First, univariate analysis was conducted in which each potential predictor variable was entered into a Cox regression model and a separate analysis conducted for each individual predictor variable. Following this univariate Cox regression analysis, each predictor variable which had a p value of ≤ 0.10 was then entered into a single multivariate Cox regression model together using the Enter method. Missing values (which was minimal), were excluded from the analysis.

Ethical approval

The present study was approved by the Royal Melbourne Human Research and Ethics Committee (reference: QA2018034).

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

In total, 707 young people presented with FEP during the study period, of which there were complete data for 700 (99.0%). The mean age at the time of entry to service was 19.5 (SD ± 2.8) years, the majority were male (60.1%, N = 425), never married (95.2%, N = 673), living with parents (65.5%, N = 463), and had comorbid substance abuse (60.1%, N = 421). At the time of service entry, 41.7% (N = 292) of young people with FEP were identified as ‘not being in employment, education or training’ (NEET). A total of 37.5% (N = 262) had a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder or schizophrenia and 16.0% (N = 112) had a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder. The median duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was 8 weeks (IQR = 2–32). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. The median duration of care was 657 days (IQR = 455–739 days).

Rate of service disengagement

A total of 394 (56.3%) young people disengaged at least once during their treatment period. Of those 394, 42.9% (N = 169) had one episode of disengagement, 27.2% (N = 107) had two episodes, 18.8% (N = 74) had three episodes and 11.2% (N = 44) had more than three episodes. The median time to disengagement was 166.5 days (SD ± 178.9, IQR 64.25–321.75) from service entry and the mean duration of the first episode of disengagement was 82 days (SD ± 83.7).

Determinants of service disengagement

Univariate Cox regression analysis of potential determinants of service disengagement revealed a number of variables that had an impact on the risk of disengaging: age was associated with an increased risk of disengaging (HR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.01–1.51, p = 0.04); not being in employment, education or training (NEET) status was associated with being 1.76 times more likely to disengage than those who were not NEET (HR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.44–2.15, p < 0.001); and individuals who had a second degree relative with a psychotic disorder had a lower risk of disengaging compared to young people who did not have a second degree relative (HR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.92, p = 0.01). Finally, exploration of the effects of substance abuse revealed that there were higher risks of disengaging for young people with concurrent substance abuse disorders compared to those who did not have substances abuse (HR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.24–1.54, p < 0.001), specifically those with concurrent cannabis abuse (HR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.20–1.48, p < 0.001), and amphetamine abuse (HR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.15–1.41, p < 0.001). There were no differences in the risks of disengagement according to; gender, a positive family history in a first-degree relative, diagnosis (non-affective vs affective psychotic disorder), and duration of untreated psychosis (Table 2).

A multivariable Cox regression analysis was conducted to control for the potential effects of confounding variables. All variables that were significant predictors (p > 0.1) in the univariate Cox regression analysis were entered into the multivariable model (Table 3). Three significant determinants of service disengagement were identified; NEET (aHR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.20–1.85, p < 0.001), cannabis use (aHR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.20–1.91, p = 0.001) and a family history of psychosis in a second-degree relative (aHR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.57–0.97, p = 0.03).

Rate and determinants of service re-engagement

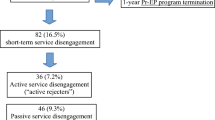

Data were available for a maximum of three episodes of re-engagement. Following the first episode of disengagement (N = 394), 85.5% (N = 337) of young people re-engaged with the service (missing data for 4 cases). A total of 225 young people had a further episode of disengagement and of these, 79.1% (N = 178) subsequently re-engaged. Of these, 118 young people had a third episode of disengagement and of these, 78.8% (N = 93) subsequently re-engaged.

The number of individuals who at any point did not re-engage was 54. This means that from the sample of 707 individuals, 7.6% disengaged and never returned to the service. Figure 1 represents a flow diagram of individuals disengaging and re-engaging with services.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of potential determinants of re-engagement was undertaken on the sub-sample of individuals who disengaged (N = 394). Predictors of re-engagement following the first episode of disengagement were explored and none were identified as significant. These results are presented in Table 4.

Data on whether individuals had a hospital admission prior to re-engaging with the EI service found that of the 335 young people who re-engaged following an initial episode of disengagement, 9.0% (N = 30) had an admission at the time of being re-engaged. Of the 178 who re-engaged following a second episode of disengagement, 4.5% (N = 8) had an admission at the time of being re-engaged and of the 95 who re-engaged following a third episode of disengagement, 13.7% (N = 13) had an admission at the time of being re-engaged.

Discussion

This is the first study in Australia to look at the rates of disengagement and subsequent re-engagement for young people accessing an EI service (EPPIC). We found that 56.3% (n = 394) of young people with FEP disengaged at least once, with 56.1% (n = 221) of those individuals disengaging more than once. This study identified three significant determinants of disengagement; NEET, comorbid cannabis use and the absence of a family history of psychosis in second-degree relatives. We found that the rate of re-engagement was high at 85.5% but did not find any significant predictors of re-engagement. The majority of individuals did not re-engage subsequent to a hospital admission.

The rate of disengagement in this cohort was higher than the rate that previous studies have shown [12]. However, our finding that only 7.6% (N = 54) of the cohort disengaged and never re-engaged with the service represents a rate of disengagement that is at the lower end of the range found in previous studies. This raises a question of whether previous studies with far higher disengagement rates have considered levels of re-engagement when calculating rates of disengagement. Variances in disengagement rates in previous studies may also be affected by the different definitions of disengagement they used. For example, using a definition of disengagement that includes a short duration of treatment refusal may result in higher disengagement rates, compared to studies that require individuals to not be in contact for longer periods of time.

The significant determinants of disengagement that we found were in accord with several other previous studies. That is, we did not find gender [22, 25] to be significant determinants of disengagement, but did find NEET at baseline and comorbid cannabis use to be significant predictors [11, 21]. Indeed, Doyle and colleagues [12] concluded that the most robust predictors of disengagement were comorbid substance abuse and a lack of involvement or support from family. The third predictor of disengagement that we found (not having a family history of psychosis in second-degree relatives) perhaps mirrors and further develops Doyle’s conclusion of the importance of family involvement. Involving family members in the treatment process is known to help promote good service engagement and they are often the first to refer individuals to mental health services [16, 26]. One explanation for the finding that absence of a family history of psychosis in second-degree relatives predicted disengagement could be that having parents/caregivers who grew up experiencing a family member with psychosis might ensure that their parents are more aware of signs, symptoms and consequences of psychosis, allowing them to recognize early warning signs in the young person and actively support them to remain engaged. Further exploration of this theory is of course required.

It is possible that there are a number of factors that play a part in predicting disengagement/re-engagement that are yet to be sufficiently explored. For example, the therapeutic relationship between client and clinician, clients’ satisfaction with services, and clinician communication style are all potential important aspects of a client’s experience of clinical services. Collecting these data as part of routine clinical care using appropriate assessments may be the important next step in developing our understanding of predictors of disengagement and subsequent re-engagement.

This is the first study to look at the rate and determinants of re-engagement, and interestingly, the rate of re-engagement we found in this study suggested that the majority of young people who disengaged from the EI service subsequently re-engaged. Furthermore, only a small number of those who re-engaged had been admitted to hospital just prior, suggesting it was not a common reason to prompt individuals to re-engage with EI services. Given that we did not identify any significant variables associated with re-engagement, further work is required to better understand the reasons for re-engagement. According to a study by Tindall and colleagues, the therapeutic relationship between case manager and young person is crucial in promoting service engagement [27] and active involvement of case managers in the treatment process and availability of outreach services might have contributed to the high rate of re-engagement in this cohort. Further work in this area might explore the relationship between the role of the case manager and re-engagement, and the subjective experience of what motivates young people to re-engage with the service. Novel ways of working to support the re-engagement of young people need to also be considered. One way of achieving this may be to involve peer support workers, whose unique role may be better attuned to support young people re-connect with services.

The finding that young people who are NEET at the time of presentation are more likely to disengage from services is important, as this represents a particularly vulnerable group. The EPPIC service demonstrated that integrating an individual placement support (IPS) worker within the clinical program can improve the gaining and retention of employment in young people with FEP [28], however, if they disengage, they cannot access this additional service and their risk of long-term unemployment is increased. The situation is similar with substance abuse, in that the EPPIC service has employed an integrative model for addressing dual diagnosis substance abuse, however, this study has demonstrated that those with cannabis abuse are more likely to disengage and, therefore, would not avail of this intervention. Therefore, in addition to introducing these interventions into other early intervention for psychosis services, thought has to be given as to how to keep these young people engaged with the services as a whole.

Limitations

While this paper represented a large, epidemiological cohort of treated cases of FEP, the results need to be considered within the limitations of the study. First, while the information was recorded prospectively, it was retained retrospectively by researchers for the purpose of this study and, therefore, the data included here were reliant on the quality of clinical record documentation. In addition, we did not perform a random audit of the data the researchers collected to ensure that errors were not occurring in their data collection. Furthermore, due to the lack of consensus on a clear definition of disengagement and the fact that disengagement is multidimensional in nature, the definition we used might not reflect all relevant aspects of disengagement. It may in fact be more beneficial for services to consider engagement as consisting of two elements—one, the literal attendance of appointments, and two, therapeutic engagement; the former being easier to measure than the latter [16]. This is an important limitation in this study where we were unable to look in-depth at levels of therapeutic engagement. Additionally, the scope of determinants of disengagement and re-engagement was limited to the number of variables we had sufficient data for, and other potential predictors such as forensic history [12, 16, 23, 29], lack of family support [16, 18,19,20,21], childhood trauma and personality factors were not examined.

Future directions

One potential way to better understand why some young people re-engaged with the service and some did not is to undertake further qualitative research. Gaining an in-depth understanding of what triggers individuals to disengage with an EI service, and then subsequently re-engage could illuminate potential novel ways to ensure young people are better supported to stay engaged with a service. One example could be to investigate how changes in symptoms contribute to disengagement or re-engagement. It is possible that a young person with symptomatic remission may choose to disengage rather than remain on a caseload and have a longer, managed discharge. Alternatively, there may be benefit in considering episodes of treatment that align to the current needs of a young person, with easy service re-entry when the young person wants it. Understanding the decisions made by a young person given what we know about the trajectory of early psychosis may be the next step to supporting young people to benefit most from the services available to them at this crucial time. We hope that the development of clinical electronic notes in recent years will allow for further analysis of a more comprehensive set of predictors in the future, including the notion of therapeutic engagement rather than engagement via attendance.

Conclusion

In this naturalistic cohort of FEP patients, a high proportion of young people disengaged from the service during the 2 years in which ongoing phase-specific interventions are indicated. However, the majority of these young people subsequently re-engaged with the service. This finding suggests that the concept of disengaging from an EI service might be more complex than previously thought with individuals disengaging and re-engaging a number of times during their episode of care (in this case, 24 months). We found that NEET at baseline, comorbid cannabis use and a negative family history in second-degree relatives were significant predictors of disengagement. We did not find any significant predictors of re-engagement. We need to better understand what prompts individuals to re-engage with services. This might come from in-depth qualitative interviews with young people who have previously disengaged and subsequently re-engaged with EI services.

References

Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C (1998) Early intervention in psychosis: the critical-period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry 172(S33):53–59

Malla A et al (2007) A Multisite Canadian Study of outcome of first-episode psychosis treated in publicly funded early intervention services. Canadian Psychiatric Association, Ottawa, p 563

Solmi F et al (2018) Predictors of disengagement from early intervention in psychosis services. Br J Psychiatry 213(2):477–483

Marshall M et al (2005) Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(9):975–983

Spencer E, Birchwood M, McGovern D (2001) Management of first-episode psychosis. Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, p 133

Iyer S et al (2015) Early intervention for psychosis: a Canadian perspective. J Nerv Ment Dis 203(5):356–364

McCrone P et al (2010) Cost-effectiveness of an early intervention service for people with psychosis. Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, p 377

Stafford MR et al (2013) Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 346:f185

Mihalopoulos C et al (2009) Is early intervention in psychosis cost-effective over the long term?. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 909

Birchwood M (2014) Early intervention in psychosis services: the next generation. Early Interv Psychiatry 8(1):1–2

Turner MA et al (2009) Outcomes for 236 patients from a 2-year early intervention in psychosis service. Acta Psychiatr Scand 120(2):129–137

Doyle R et al (2014) First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv 65(5):603–611

Chan TC et al (2014) Rate and predictors of disengagement from a 2-year early intervention program for psychosis in Hong Kong. Schizophr Res 153(1–3):204–208

Garety PA, Rigg A (2001) Early psychosis in the inner city: a survey to inform service planning. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36(11):537–544

Turner M, Smith-Hamel C, Mulder R (2007) Prediction of twelve-month service disengagement from an early intervention in psychosis service. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, London, p 276

Conus P et al (2010) Rate and predictors of service disengagement in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. Schizophr Res 118(1–3):256–263

Miller R et al (2009) A prospective study of cannabis use as a risk factor for non-adherence and treatment dropout in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 113:138–144

Schimmelmann BG et al (2006) Predictors of service disengagement in first-admitted adolescents with psychosis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:990–999

Stowkowy J et al (2012) Predictors of disengagement from treatment in an early psychosis program. Schizophr Res 136(1–3):7–12

Anderson KK et al (2013) Determinants of negative pathways to care and their impact on service disengagement in first-episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(1):125–136

Zheng S, Poon LY, Verma S (2013) Rate and predictors of service disengagement among patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 64(8):812–815

Casey D et al (2016) Predictors of engagement in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 175:204–208

Spidel A et al (2015) A comparison of treatment adherence in individuals with a first episode of psychosis and inpatients with psychosis. Int J Law Psychiatry 39:90–98

Lau KW et al (2017) Rates and predictors of disengagement of patients with first‐episode psychosis from the early intervention service for sychosis service (EASY) covering 15 to 64 years of age in Hong Kong. Early Interv Psychiatry

O’Brien A et al (2009) Disengagement from mental health services. A literature review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(7):558–568

Tindall RM et al (2018) Essential ingredients of engagement when working alongside people after their first episode of psychosis: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Early Interv Psychiatry 12(5):784–795

Tindall R, Francey S, Hamilton B (2015) Factors influencing engagement with case managers: perspectives of young people with a diagnosis of first episode psychosis. Int J Ment Health Nurs 24(4):295–303

Killackey E, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2008) Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry 193(2):114–120

Lecomte T et al (2008) Predictors and profiles of treatment non-adherence and engagement in services problems in early psychosis. Schizophr Res 102:295–302

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D.J., Brown, E., Reynolds, S. et al. The rates and determinants of disengagement and subsequent re-engagement in young people with first-episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 945–953 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01698-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01698-7