Abstract

Purpose

To explore the roles of proportion of social rented housing in the neighbourhood (‘neighbourhood social housing’), own housing being socially rented, and their interaction in early trajectories of emotional, conduct and hyperactivity symptoms. We tested three pathways of effects: family stress and maternal psychological distress, low quality parenting practices, and peer problems.

Methods

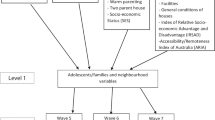

We used data from 9,850 Millennium Cohort Study families who lived in England when the cohort children were aged 3. Children’s emotional, conduct and hyperactivity problems were measured at ages 3, 5 and 7.

Results

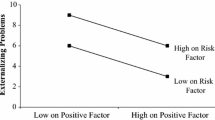

Even after accounting for own social housing, neighbourhood social housing was related to all problems and their trajectories. Its association with conduct problems and hyperactivity was explained by selection. Selection also explained the effect of the interaction between neighbourhood and own social housing on hyperactivity, but not why children of social renter families living in neighbourhoods with lower concentrations of social housing followed a rising trajectory of emotional problems. The effects of own social housing, neighbourhood social housing and their interaction on emotional problems were robust. Peer problems explained the association of own social housing with hyperactivit y.

Conclusions

Neither selection nor the pathways we tested explained the association of own social housing with conduct problems, the association of neighbourhood social housing with their growth, or the association of neighbourhood social housing, own social housing and their interaction with emotional problems. Children of social renter families in neighbourhoods with a low concentration of social renters are particularly vulnerable to emotional problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Van Ham M, Manley D (2012) Neighbourhood effects research at a crossroads: ten challenges for future research. Environ Plann A 44:2787–2793. doi:10.1068/a45439

Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J (2000) The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence upon child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull 126:309–337. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.918

Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM (2011) Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol 62:189–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412

Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Winslow E et al (2006) Neighborhood disadvantage, parent-child conflict, neighborhood peer relationships, and early antisocial behavior problem trajectories. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34:293–309. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9026-y

Haynie DL, Osgood DW (2005) Reconsidering peers and delinquency: how do peers matter? Soc Forces 84:1109–1130. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0018

Light JM, Dishion TJ (2007) Early adolescent antisocial behavior and peer rejection: a dynamic test of a developmental process. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 118:77–89. doi:10.1002/cd.202

Linares L, Heeren T, Bronfman E et al (2001) A mediational model for the impact of exposure to community violence on early child behavior problems. Child Dev 72:639–652. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00302

Odgers CL, Caspi A, Russell MA et al (2012) Supportive parenting mediates widening neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children’s antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Dev Psychopathol 24:705–721. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000326

Randall C (2011) Social trends 41: housing. Office for National Statistics, London (ISSN 2040-1620)

Feinstein L, Lupton R, Hammond C et al (2008) The public value of social housing: a longitudinal analysis of the relationship between housing and life chances. The Smith Institute, London

Lawder R, Walsh D, Kearns A, Livingston M (2014) Healthy mixing? Investigating the associations between neighbourhood housing tenure mix and health outcomes for urban residents. Urban Stud 51:1–20. doi:10.1177/0042098013489740

Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, Schulz H (2001) Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: prevalence and school factors. Brit J Psychol 92:673–696. doi:10.1348/000712601162419

Mulvaney C, Kendrick D (2005) Depressive symptoms in mothers of pre-school children: effects of deprivation, social support, stress and neighbourhood social capital. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:202–208. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0859-4

Snijders T, Bosker R (1999) Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and applied multilevel analysis. Sage, Newbury Park

Hansen K, Jones E, Joshi H, Budge D (2010) Millennium cohort study fourth survey: a user’s guide to initial findings. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London, London

Wakschlag LS, Gordon RA, Lahey BB et al (2000) Maternal age at first birth and boys’ risk for conduct disorder. J Res Adolesc 10:417–441. doi:10.1207/SJRA1004_03

Hawkes D, Joshi H (2012) Age at motherhood and child development: evidence from the UK millennium cohort. Nat Inst Econ Rev 222:R52–R66. doi:10.1177/002795011222200105

Egger HL, Angold A (2006) Common emotional and behavioural disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:313–317. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x

Goodman A, Patel V, Leon DA (2008) Child mental health differences amongst ethnic groups in Britain: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 8:258. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-258

Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford T (2003) Mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. Int Rev Psychiatry 15:185–187. doi:10.1080/0954026021000046155

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Stone LL, Otten R, Engels RC, Vermulst AA, Janssens JM (2010) Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13:254–274. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2

Tiet QQ, Bird HR, Davies M et al (1998) Adverse life events and resilience. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:1191–1200. doi:10.1097/00004583-199811000-00020

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ et al (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:184–189. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

Ginther D, Haveman R, Wolfe B (2000) Neighborhood attributes as determinants of children’s outcomes: how robust are the relationships? J Hum Resour. 35:603–642. doi:10.2307/146365

Goldstein H (2003) Multilevel statistical models, 3rd edn. Arnold Publishers, London

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods, 2nd edn. Sage, Newbury Park

Dietz RD, Haurin DR (2003) The social and private micro-level consequences of homeownership. J Urban Econ 54:401–450. doi:10.1016/S0094-1190(03)00080-9

Scott S, Sylva K, Doolan M et al (2010) Randomised controlled trial of parent groups for child antisocial behaviour targeting multiple risk factors: the SPOKES project. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:48–57. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02127.x

Acknowledgments

This paper was written while EF and EM were supported by grant ES/J001414/1 from the UK Economic and Social Research Council. The work presented here extends the work submitted by KT for her Master’s dissertation (supervised by EF and EM) in Special and Inclusive Education. We are very grateful to Heather Joshi for her useful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flouri, E., Midouhas, E. & Tzatzaki, K. Neighbourhood and own social housing and early problem behaviour trajectories. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 203–213 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0958-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0958-1