Abstract

Background

Analysis of the Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of Great Britain showed that the prevalence of common mental disorders was lower amongst men at or above Britain’s state pension age of 65, relative to younger men. Retirees below this age had consistently higher rates of mental disorders than working men. In contrast, the low prevalence of mental disorders amongst retirees aged 65 and older was similar to that of their working peers. The aim of this analysis was to investigate this pattern of results in a national sample of Australian men, and the mediating role of socio-demographic factors.

Method

Data were from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) in Australia survey (2003). The analyses included men aged 45–74 years who were active in the labour force (n = 1309), or retired (n = 635). Mental health was assessed using the mental health scale from the Short-Form 36 Health Questionnaire.

Results

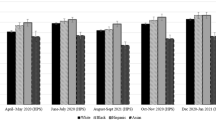

Retirees were more likely to have mental health problems than their working peers, however this difference was progressively smaller across age groups. For retirees above, though not below, the age of 55 this difference was explained by poorer physical functioning. When age at retirement was considered it was found that early retirees who were now at or approaching the conventional retirement age did not display the substantially elevated rates of mental health problems seen in their younger counterparts. Further, men who had retired at age 60 or older did not display an initially elevated rate of mental health problems.

Conclusions

The association between retirement and mental health varies across older adulthood. Retired British and Australian men below the conventional retirement age of 65 are more likely to have mental health problems relative to their working peers, and retirees above this age. However, poor mental health appears to be linked to being retired below this age rather than an enduring characteristic of those who retire early.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These estimates are consistent with recent economic reviews, which report that additional social security benefits, such as disability (known in Britain as invalidity), mature-age, and unemployment allowances, may act as an avenue to early retirement for discouraged job-seekers, and older adults with poor health [8, 11].

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001) Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Area’s (SEIFA), Australia – Technical Paper, Cat. No. 6238.0. ABS, Canberra

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1997) Retirement and Retirement Intentions, Cat. No. 6238.0. ABS, Canberra

Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC (1991) Performance of a 5-item mental-health screening-test. Med Care 29:169–176

Bosse R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR, Ekerdt DJ (1987) Mental health differences among retirees and workers: findings from the normative aging study. Psychol Aging 2:383–389

Butterworth P, Crosier T (2004) The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health 4:1–11

Butterworth P, Gill SC, Rodgers B, Anstey KJ, Villamil E, Melzer D (2006) Retirement and mental health: analysis of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Soc Sci Med 62:1179–1191

Buxton JW, Singleton N, Melzer D (2005) The mental health of early retirees – National interview survey in Britain. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:99–105

Carey D (1999) Coping with population ageing in Australia. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 217. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Dooley D, Fielding J, Levi L (1996) Health and unemployment. Ann Rev Public Health 17:449–465

Drentea P (2002) Retirement and mental health. J Aging Health 14:167–194

Duval R (2003) The retirement effects of old-age pension and early retirement schemes in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 370. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Hagestad GO, Neugarten BL (1985) The social aspects of aging. In: Binstock RH, Shanas E (eds) Handbook of aging and the social sciences. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, pp 35–61

Herzog AR, House JS, Morgan JN (1991) Relation of work and retirement to health and well-being in older age. Psychol Aging 6:202–211

Holmes WC (1998) A short, psychiatric, case-finding measure for HIV seropositive outpatients: performance characteristics of the 5-item mental health subscale of the SF-20 in a male, seropositive sample. Med Care 36:237–243

Jackson PR, Warr PB (1984) Unemployment and psychological ill-health: the moderating role of age. Psychol Med 14:605–614

Mathers CD, Schofield DJ (1998) The health consequences of unemployment: the evidence. Med J Australia 168:178–182

Mein G, Martikainen P, Hemingway H, Stansfeld S, Marmot M (2003) Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. J Epidemiol Commun Health 57:46–49

Melzer D, Buxton J, Villamil E (2004) Decline in common mental disorder prevalence in men during the sixth decade of life – Evidence from the National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:33–38

Moen P (1996) A life course perspective on retirement, gender, and well-being. J Occupation Health Psychol 1:131–144

Murphy GC, Athanasou JA (1999) The effect of unemployment on mental health. J Occupation Organization Psychol 72:83–99

O’Rand AM (1990) Stratification and the life course. In: Binstock RH, George LK (eds) Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

Palmore EB, Fillenbaum GG, George LK (1984) Consequences of retirement. J Gerontol 39:109–116

Richardson VE, Kilty KM (1995) Gender differences in mental health before and after retirement: a longitudinal analysis. J Women Aging 7:19–35

Ross CE, Drentea P (1998) Consequences of retirement activities for distress and the sense of personal control. J Health Soc Behav 39:317–334

Rowley KM, Feather NT (1987) The impact of unemployment in relation to age and length of unemployment. J Occupation Psychol 60:323–332

Rumpf H-J, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U (2001) Screening for mental health: validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res 105:243–253

Scherer P (2002) Labour market and social policy – Occasional Papers No. 49, Age of withdrawal from the labour force in OECD countries. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Araya R, Jones K, Williams G (2005) Mental health inequalities in Wales, UK: multi-level investigation of the effect of area deprivation. Br J Psychiatry 186:417–422

Szinovacz ME, DeViney S (1999) The retiree identity: gender and race differences. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Social Sci 54:S207–S218

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual Framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B (1997) SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre, Boston, MA

Watson N (2004) Wave 2 Weighting. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series 4

Watson N, Wooden M (2002) Assessing the quality of the HILDA survey wave 1 data. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series 4

Watson N, Wooden M (2002) The household, income and labour dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey: Wave 1 Survey Methodology. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series 1

World Health Organization (1993) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. WHO, Geneva

Yamazaki S, Fukuhara S, Green J (2005) Usefulness of five-item and three-item Mental Health Inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population in Japan. Health Qual Life Outcomes 3:48–54

Acknowledgements

The HILDA survey was initiated and is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (MIAESR). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either FaCS or the MIAESR. Sarah Gill was supported by NHMRC Public Health Postgraduate Scholarship No. 316982. Peter Butterworth was supported by NHMRC Public Health (Australia) Fellowship No. 316970. Bryan Rodgers was supported by NHMRC Research Fellowship No. 148948. Kaarin Anstey was supported by NHMRC Research Fellowship No. 179839.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gill, S.C., Butterworth, P., Rodgers, B. et al. Mental health and the timing of Men’s retirement. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 41, 515–522 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0064-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0064-0