Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We aimed to investigate the associations between maternal diabetes before or during pregnancy and the risk of high refractive error (RE) in offspring until the age of 25 years.

Methods

This nationwide register-based cohort study comprised 2,470,580 individuals born in 1977–2016. The exposure was maternal diabetes during or before pregnancy (type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes). Cox regression was used to examine the association between maternal diabetes and the risk of high RE in offspring from birth until the age of 25 years, adjusting for multiple potential confounders.

Results

During up to 25 years of follow-up, 553 offspring of mothers with diabetes and 19,695 offspring of mothers without diabetes were diagnosed with high RE. Prenatal exposure to maternal diabetes was associated with a 39% increased risk of high RE: HR 1.39 (95% CI 1.28, 1.51), p < 0.001; standardised cumulative incidence in unexposed offspring at 25 years of age 1.18% (95% CI 1.16%, 1.19%); cumulative incidence difference 0.72% (95% CI 0.51%, 0.94%). The elevated risks were observed for hypermetropia (HR 1.37 [95% CI 1.24, 1.51], p < 0.001), myopia (HR 1.34 [95% CI 1.08, 1.66], p = 0.007) and astigmatism (HR 1.58 [95% CI 1.29, 1.92], p < 0.001). The increased risks were more pronounced among offspring of mothers with diabetic complications (HR 2.05 [95% CI 1.60, 2.64], p < 0.001), compared with those of mothers with diabetes but no diabetic complications (HR 1.18 [95% CI 1.02, 1.37], p = 0.030).

Conclusions/interpretation

Our findings suggest that maternal diabetes during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of high RE in offspring, in particular among those of mothers with diabetic complications. Early ophthalmological screening should be recommended in offspring of mothers with diabetes diagnosed before or during pregnancy.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Refractive errors (REs) are the failure of the eye to focus images on the retina, as a result of pathophysiological changes of ocular refractive components [1]. RE is among the most common vision impairment and is the second leading cause of disability globally [2]. Low-degree REs can be corrected optically with a low risk of ocular complications but high REs (e.g. hypermetropia, myopia, astigmatism) can often develop into irreversible severe visual impairment, resulting in lifelong reduced quality of life [3, 4]. A rapid increase in the prevalence of RE has been seen over the past decades [1], indicating that non-genetic risk factors may play an important role. Long periods of near work and lack of outdoor activity have been established as the main acquired risk factors for low- and moderate-degree REs in school-age children and young adults [5] but the aetiology of high RE is still not fully understood [1]. Many have shown that individuals with high RE may have congenital refractive defects before their birth [6,7,8], suggesting that a pathological intrauterine environment may play a role in the development of high RE later in life.

The increasing prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy has resulted in a global epidemic [9,10,11]. Diabetes-induced changes in blood vessels, dysfunction of endothelial cells and disturbance of pericyte–endothelial cell crosstalk are the initiating factors in the genesis of most diabetic complications [12,13,14]. Large cohort studies have demonstrated that maternal diabetes may affect the development of vasculopathy and metabolic diseases in offspring via the diabetic intrauterine environment [15, 16]. An intact blood–ocular vascular endothelial barrier and metabolic homeostasis in the eyes are critical for healthy eyesight [17], whereas fluctuation of blood glucose levels may impair the blood–ocular barrier and lead to transient refractive changes or even permanent RE, as observed in the general population [18]. It has been suggested that the development of RE in offspring may partly be attributed to intrauterine exposure to high levels of glucose, particularly in pregnancies with diabetic complications [19]. Two small studies have reported the association between diabetic status of mothers and REs in offspring [20, 21]. However, the aetiological importance is limited by the cross-sectional design of these studies. It remains unknown whether or to what extent prenatal exposure to maternal diabetes increases the risk of high RE in offspring in childhood and young adulthood.

We hypothesised that intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes could lead to pathophysiological changes that contribute to the development of high RE in offspring [19,20,21]. In this large population-based cohort study, we aimed to investigate the associations between maternal diabetes before or during pregnancy and the risk of high RE in offspring until the age of 25 years. We further expected that the most pronounced associations would be observed among offspring of mothers with diabetic complications [18, 22], a proxy of more severe diabetes.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a population-based cohort study using Danish national registers (detailed descriptions of the registers are provided in electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). The unique personal identification number assigned to all Danish residents allows accurate linkage of individual-level information across registries. We included 2,470,580 live births in Denmark from 1977 to 2016 identified from the Danish Medical Birth Register [23]. Follow-up started from birth and ended at the first occurrence of a high RE diagnosis, death, emigration, 31 December 2016, or offspring’s 25th birthday, whichever came first. People who emigrated or died during follow-up were censored at the time of emigration or death.

The study was approved by the Data Protection Agency (Record No. 2013-41-2569). By Danish law, no informed consent is required for a register-based study based on anonymised data.

Procedures

Mothers were considered to have diabetes if they received a diagnosis of diabetes before or during pregnancy. We similarly defined diabetes in fathers. Information on diabetes diagnosis was retrieved from the Danish National Diabetes Register [24], the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) [25] and the Danish National Prescription Registry [26] using ICD-8 codes during 1970–1993 (wolfbane.com/icd/icd8.htm), ICD-10 codes from 1994 onwards (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en), and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification codes. Maternal diabetes was categorised as gestational diabetes (GDM; ICD-8 codes 634.74, Y6449; ICD-10 codes O24.4, O24.9) or pre-gestational diabetes (ICD-8 codes 249, 250; ICD-10 codes E10-E11, H36.0, O24 [excluding O24.4 and O24.9]). We also ascertained pre-gestational diabetes using the diagnosis of diabetic chiropody and the prescriptions of insulin (ATC code A10A) or oral glucose-lowering drugs (ATC code A10B) if two redeemed prescriptions were recorded within 6 months. Pre-gestational diabetes was further defined as type 1 diabetes (ICD-8 code 249; ICD-10 codes E10, O24.0; ATC code A10A) or type 2 diabetes (ICD-8 code 250; ICD-10 codes E11, O24.1; ATC code A10B) before pregnancy. The methods used to identify diabetes are summarised in ESM Table 2. If a mother was diagnosed with multiple types of diabetes during one pregnancy due to possible misclassification error, she was classified according to the first diagnosed type. We identified mothers with pre-gestational diabetic complications and further categorised them into two subgroups: mothers with one complication; and mothers with multiple complications. Diabetic complications were defined as diabetic coma, ketoacidosis, and diabetes with kidney, ophthalmic, neurological, circulatory, unspecified or multiple complications, recorded in the DNPR.

The primary outcome of interest was high RE in offspring, defined as the first occurrence of RE recorded in the DNPR (ICD-8 codes 37,001–37,009; ICD-10 codes H52.0–H52.7) [25]. The secondary outcomes were specific types of high RE, including hypermetropia, myopia, astigmatism, and other types of RE (ICD codes are provided in ESM Table 3).

We selected several potential confounders as covariates using directed acyclic graphs (ESM Fig. 1). Information on maternal age (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34 or ≥35 years), parity (1, 2 or ≥3), maternal marital status (single or married), maternal smoking status during pregnancy (yes or no), singleton delivery (yes or no), sex of offspring (male, female) and calendar period of delivery (before 1980, 1981–1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010 or 2011–2016) were retrieved from the Danish Medical Birth Registry [23]; maternal educational level (0–9, 10–14 or ≥15 years), maternal residence (Copenhagen, cities with ≥100,000 inhabitants, or other places) were retrieved from the Danish Integrated Database for Longitudinal Labour Market Research [27]; parental high RE history before the birth of the child (yes or no) was retrieved from the DNPR [25]. Detailed information on missing data for covariates is summarised in ESM Table 4. Missing indicators were created for variables with missing values.

Statistical analyses

We performed competing risk analyses by treating deaths as the competing events to estimate the cumulative incidence among exposed and unexposed offspring using the inverse probability of treatment weighting approach [28]. Cox regression was used to estimate HRs with 95% CIs to assess the association between prenatal exposure to maternal diabetes and overall/specific high RE in offspring. The offspring’s age was used as the time scale and robust variance was used to account for the correlations between siblings. As pre-gestational diabetic complications may reflect the severity of pre-gestational diabetes, we further examined the association between maternal diabetes and high RE in offspring by the presence of maternal diabetic complications. For ocular refractive development, as the visual environment and eye-using behaviour vary significantly during different age stages in early life [8] (ESM Fig. 2), we examined the association between maternal diabetes and high RE in offspring according to the age group of the offspring (0–3, 4–15 and 16–25 years).

We performed nine sensitivity analyses. First, sibling design was used to account for shared familial factors [29]. As the presence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes would not change between pregnancies and GDM was more common in older women with high parity, the sibling design was appropriate for GDM in a second or later pregnancy. Second, we used paternal diabetes as the negative control exposure to explore potential residential confounding or information bias from genetic factors and shared familial factors such as diabetes-related environment, behaviours and hospital contacts. Third, since diabetes is typically preceded by a period of prediabetes, we evaluated the risk of high RE in offspring in relation to the timing of maternal diabetes diagnosis with respect to childbirth (pre-gestational diagnoses before conception and diagnoses within ≤2, 2–5 and >5 years after childbirth). Fourth, we restricted our analyses to offspring born to mothers with only one type of diabetic diagnosis, to examine whether the associations were affected by the definition of diabetes. Fifth, to account for the influence on RE onset from congenital ocular malformations, we excluded offspring with congenital ocular malformations. Sixth, because the development of the visual and oculomotor systems is substantially affected in offspring with Down syndrome [30], we further excluded children with Down syndrome. Seventh, because the refractive status is highly associated with diabetes in offspring, and offspring of diabetic mothers have a higher risk of being diagnosed with diabetes in the first 25 years of life [31], we excluded offspring with a diabetes diagnosis to examine the association. Eighth, to take into consideration the influence of ICD code changes since 1994, we restricted a sub-analysis to offspring born after 1994. In addition, considering the fact that GDM screening was not officially endorsed until 1998, which might result in differences in GDM identification, we did separate analyses, namely, restricting the analyses to offspring born before 1998 and to offspring born since 1998. Ninth, we adjusted for maternal family history of diabetes and maternal BMI before pregnancy, restricted to firstborn offspring, to evaluate the potential impact of GDM screening practice. Inverse probability of selection weighting was used to evaluate possible live-birth bias [32], considering that maternal diabetes could lead to fetal loss and, therefore, naive analysis of data on live births could be misleading [32, 33].

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, UAS). All p values were two-sided and a significance level of 0.05 was applied.

Results

Of 2,470,580 liveborn individuals, 56,419 (2.3%) were exposed to maternal pre-gestational diabetes (type 1 diabetes 0.9%, type 2 diabetes 0.3%) or GDM (1.1%). The proportion of offspring born to mothers with diabetes increased over time, from 0.4% in 1977 to 6.5% in 2016. Compared with non-diabetic mothers, mothers with diabetes were more likely to be older, well-educated, have a higher parity and live alone. Compared with offspring born to mothers with no diabetes, those born to mothers with diabetes were more likely to have a parental history of RE (Table 1).

Main findings

During the follow-up period of up to 25 years, 553 offspring of mothers with diabetes and 19,695 offspring of non-diabetic mothers were diagnosed with high RE. Exposed offspring had a 39% increased risk of overall high RE than unexposed offspring: HR 1.39 (95% CI 1.28, 1.51), p < 0.001 (Table 2); standardised cumulative incidence at 25 years of age 1.18% (95% CI 1.16%, 1.19%) in unexposed offspring (Fig. 1); cumulative incidence difference between exposed and unexposed offspring 0.72% (95% CI 0.51%, 0.94%) (Fig. 1). While the estimated risks for high RE associated with exposure to pre-gestational diabetes (HR 1.40 [95% CI 1.25, 1.57], p < 0.001) and GDM (HR 1.37 [95% CI 1.21, 1.55], p < 0.001) were similar, the risk associated with exposure to maternal type 2 diabetes seemed to be higher (HR 1.68 [95% CI 1.36, 2.08], p < 0.001) than that associated with type 1 diabetes (HR 1.32 [95% CI 1.15, 1.51], p < 0.001) (Table 2). The HR (95% CI) for hypermetropia, myopia and astigmatism was 1.37 (1.24, 1.51) (p < 0.001), 1.34 (1.08, 1.66) (p = 0.007) and 1.58 (1.29, 1.92) (p < 0.001), respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1). The increased risk of high RE was observed in all three age groups: under 3 years (HR 1.55 [95% CI 1.35, 1.79], p < 0.001); 4–15 years (HR 1.23 [95% CI 1.10, 1.39], p < 0.001); and 16–25 years (HR 1.56 [95% CI 1.19, 2.03], p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). When compared with unexposed offspring, offspring of mothers with diabetic complications were at a significantly higher risk of high RE (HR 2.05 [95% CI 1.60, 2.64], p < 0.001) than the offspring of mothers with pre-gestational diabetes but no diabetic complications (HR 1.18 [95% CI 1.02, 1.37], p = 0.030) (Table 3).

Adjusted cumulative incidence of RE onset among offspring exposed vs unexposed to maternal diabetes. The adjusted cumulative incidence was averaged across the distribution of the covariates (calendar year, sex, singleton status, parity, age, smoking, education, cohabitation, residence at childbirth, history of RE before childbirth, and paternal history of RE before birth of the child) using the inverse probability of treatment weighting approach. (a) Overall RE. (b) Hypermetropia. (c) Myopia. (d) Astigmatism. CID, cumulative incidence difference

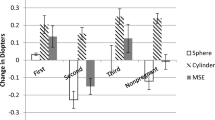

Associations between different types of maternal diabetes and RE onset by offspring age (a), and between maternal diabetes and specific RE onset in offspring by offspring age (b). Associations were controlled for calendar year, sex, singleton status, parity, maternal smoking, maternal education, maternal cohabitation, maternal residence at birth, maternal history of RE before childbirth, paternal history of RE before birth of the child, and maternal age

Sensitivity analyses

Sibling design revealed almost identical results (HR 1.41 [95% CI 1.01, 1.98]) to those of the main analyses in the unmatched whole population cohort. Paternal diabetes was not associated with high RE onset in offspring (HR 0.95 [95% CI 0.80, 1.13]) (ESM Table 5). Concerning the timing of maternal diabetes diagnosis, the association of maternal diabetes with RE was strongest when mothers were diagnosed before childbirth (HR 1.45 [95% CI 1.29, 1.62]), and attenuated over time after birth (ESM Table 6). Results from the following sub-analyses are presented in ESM Tables 7–12, respectively: (1) restricting to offspring of mothers diagnosed with only one diabetes type during their pregnancy; (2) excluding the 9463 offspring with a diagnosis of congenital eye malformation; (3) excluding 2281 offspring with Down syndrome; (4) excluding the 31,628 offspring with a diagnosis of diabetes; (5) restricting to offspring born before 1994, since 1994, before 1998, and since 1998; and (6) adjusted for maternal family history of diabetes, maternal BMI before pregnancy, and restricted to firstborn offspring.

Discussion

Principal findings and exploration of possible mechanisms

In this nationwide population-based cohort study, we observed that offspring born to mothers with either pre-gestational diabetes or GDM were at an increased risk of developing high RE in general, as well as specific types of high RE, persisting from the neonatal period to early adulthood. Offspring born to mothers with diabetic complications had the highest risk of high RE.

There are several potential explanations for the associations observed in our study. First, for pregnant women with diabetes, elevated levels of maternal serum glucose can lead to hyperglycaemia in the fetal circulation via the placenta [19]. In the fetus, hyperglycaemia may induce vascular endothelial dysfunction and neuropathy [12, 34]. This may result in the leakage or breakdown of the blood–ocular barrier endothelial system [17, 18], in turn leading to aqueous humour osmotic pressure changes and subsequent RE after birth [18, 35, 36]. This assumption has been supported by a study using a chick embryo model in which a high concentration of glucose injected on embryo development day (EDD) 1 resulted in 47.3% of embryonic eye malformations occurring on EDD 5 [37]. Second, enhanced oxidative stress and inflammatory responses due to hyperglycaemia may damage the retina or optic nerve [12, 38, 39]. Offspring born from diabetic pregnancies (offspring of pregnant women with pre-gestational diabetes or GDM) also likely had significantly lower pericentral macular retinal variables and higher risk of superior segmental optic nerve hypoplasia, compared with offspring born from non-diabetic pregnancies [40, 41]. Visual inputs play an important role in eye growth by affecting the amplitude of accommodation of the eyes, so the subnormal visual feedback may indirectly influence the development of the refractive system in early life and the affected offspring may be predisposed to develop RE [42].

We further found that children of mothers with diabetic complications had a significantly elevated risk of high RE. Previous observations show that maintaining strict glycaemic control before or during pregnancy is essential to prevent pregnancy-related complications and offspring congenital malformations [43]. These findings support the notion that the presence of diabetic complications could be considered as a key indicator of severe hyperglycaemia-related vasculopathy, neuropathy and retinopathy and are important contributors to metabolic and haemodynamic changes [22] that might be involved in refractive development regulation [18].

It was interesting to observe that hypermetropia occurred more frequently in childhood and myopia was more frequent in adolescence and young adulthood. This difference might be due to the natural process of emmetropisation, which could correct most hyperopia in early infancy over time [44]. In addition, the increasing years and intensity of school education could increase the risk of myopia from early childhood to young adulthood [1]. It is important to note increased RE risks for offspring exposed to maternal diabetes in all age groups (<3 years, 4–15 years and 16–25 years), regardless of the type of maternal diabetes, although HRs slightly varied across the three age groups. This suggests that maternal diabetes-induced intrauterine ocular impairment may contribute to the impeded emmetropisation at an early age or subnormal refractive accommodation during the eye growth in childhood and adulthood. Over time, these underlying mechanisms may further lead to the elevated risk of developing high RE.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Our study has the strengths of high-quality long-term follow-up data covering the whole Danish population, thus minimising the possibility of selection bias and recall bias. The large sample size enabled us to investigate specific types of RE and the risk of long-term consequences with sufficient statistical power. Furthermore, the availability of sociodemographic and medical information provided us with the opportunity to adjust for a wide range of important covariates and to conduct detailed analyses to examine our specific research questions.

Several limitations should be noted. First, although we used multiple approaches to identify outcomes and exposures, as commonly done in previous register-based studies in Denmark [16], we could not rule out the possibility of potential misclassification of exposure (maternal diabetes). For example, we might misclassify the type of pre-gestational diabetes before 1986 when separate ICD codes for type 1 and type 2 diabetes were not available [45]. However, our analysis that was restricted to different birth years yielded results similar to those in the primary analysis. For some individuals, type 2 diabetes might also be misclassified as type 1 diabetes if the individual required insulin treatment. However, this misclassification was unlikely to change the overall association, as the estimates for type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes were similar in our study. Some mothers with diabetes might be misclassified as ‘no diabetes’ if not referred to the hospital. However, the ascertainment and verification of diabetes in Denmark are considered highly reliable [46]. Furthermore, the misclassification is likely non-differential and would most likely attenuate the risk estimates to the null. GDM is also likely to be underreported in the first half of the observational period, as screening for GDM was not officially endorsed in Denmark until 1998 and not affected by family history of diabetes, previous birth of a heavy baby or the mother being overweight. However, the finding from the sensitivity analyses indicated that bias from the underreporting of GDM before 1998, family history of diabetes, previous birth of a heavy baby, or the mother being overweight would not significantly alter our main finding. Second, not all REs are recorded in the DNPR; recording mainly depends on the severity of RE and whether or not an ophthalmological examination was carried out. Because we could only identify high RE from the DNPR, this prevented us from estimating the overall RE risk of offspring born to mothers with diabetes status during or before pregnancy. However, this is the best available evidence so far, and future cohort studies with complete coverage of RE diagnosis are well warranted. For offspring whose REs were identified by more frequent hospital contacts, if the hospital contact-related factors were non-differential between the exposed and the non-exposed, the associations would mostly be attenuated towards the null. If hospital contacts arose from diabetes-related ophthalmic examinations for both offspring and mother, then our finding is prone to a risk of information bias. However, our sensitivity analyses, for the association in offspring without diabetes and for the association between paternal diabetes and RE risk in offspring, suggest that our findings were less likely to be attributed to this information bias. Third, we could not completely eliminate the residual confounding from familial factors such as outdoor activities, glycaemic control, diet and nutrition, and genetic factors. However, our sibling analyses, which might account for the potential confounding of unmeasured but stable familial factors [47], showed similar results to those of the unpaired design based on the whole cohort. In addition, findings of the attenuated association of maternal diabetes diagnosed after childbirth and non-association of paternal diabetes with high RE in offspring suggest that familial and genetic effects are unlikely to be entirely attributable to uncontrolled confounding. Fourth, we cannot rule out the possibility of live-birth bias because the offspring who died in early pregnancy are undiagnosed.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Two cross-sectional studies have reported that maternal diabetes was associated with RE in offspring [20, 21]. One, including 350 children from an outpatient clinic of a paediatric hospital, reported that children of mothers with GDM had a threefold greater risk of having RE than children born to mothers without GDM. However, the study focused solely on hypermetropia and myopia in children younger than 5 years of age and did not adjust for important potential confounders such as maternal socioeconomic status, probably due to availability of data [20]. The other cross-sectional study, of 33 neonates, reported that mean spherical equivalent for both eyes in children born to mothers with diabetes was significantly greater than that of children born to mothers without diabetes, indicating that maternal diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hypermetropia in newborns [21]. In addition, greater central corneal thickness was found in children of mothers with diabetes [21], suggesting an elevated risk of developing myopia in the future, as central corneal thickness is positively associated with the degree of myopia in young adults [48].

Our study is the first population-based cohort study to show that maternal diabetes may affect the development of high RE in offspring, persisting into adulthood. We were able to examine the effects of both pre-gestational diabetes and GDM on the subtypes of high RE. We believe that our study provides better evidence on the association, attributable to the much longer follow-up into early adulthood (25 years of age) and the large sample size of a full population-based approach in a country, taking into consideration a number of potential confounders.

Meaning of the study

As many REs in young children are treatable, early identification and intervention can have a lifelong positive impact. Therefore, although the 39% increased risk is a relatively low effect size, from a public health perspective, considering the high global prevalence of REs [49], any tiny improvement in this low-risk preventable factor will contribute to a huge reduction in absolute incidence of REs [5]. Thus, the value of early ophthalmological screening should be evaluated in offspring of mothers with diabetes, especially those with diabetic complications, before or during pregnancy for their eyesight health in the future.

Unanswered questions and future research

Our findings support the idea that positive glucose control in mothers with GDM or pre-gestational diabetes is crucial for reducing high RE risk in offspring. However, we still lack sufficient information on the evaluation of the severity of maternal diabetes and the effects of glucose control. Thus, a validation study with comprehensive exposure assessment is warranted.

Data availability

The data used is stored at the secure platform of Denmark Statistics, which is the central authority on Danish statistics with the mission to collect, compile and publish statistics on the Danish society. Due to restrictions related to Danish law and protecting patient privacy, the combined set of data as used in this study can only be made available through a trusted third party, Statistics Denmark (www.dst.dk/en/kontakt). This state organisation holds the data used for this study. University-based Danish scientific organisations can be authorised to work with data within Statistics Denmark and such organisations can provide access to individual scientists inside and outside of Denmark. Researchers can apply for access to these data when the request is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (www.datatilsynet.dk; the e-mail address for the Danish Data Protection Agency is dt@datatilsynet.dk). Requests for data may be sent to Statistics Denmark: www.dst.dk/en/OmDS/organisation/TelefonbogOrg.aspx?kontor=13&tlfbogsort=sektion or the Danish Data Protection Agency: www.datatilsynet.dk.

Abbreviations

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- DNPR:

-

Danish National Patient Registry

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes

- RE:

-

Refractive error

References

Morgan IG, Ohno-Matsui K, Saw S-M (2012) Myopia. Lancet 379(9827):1739–1748. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60272-4

World Health Organization (2008) The global burden of disease: 2004 update. WHO Press, Geneva

Rahi JS, Cable N (2003) Severe visual impairment and blindness in children in the UK. Lancet 362(9393):1359–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14631-4

Rahi JS, Solebo AL, Cumberland PM (2014) Uncorrected refractive error and education. BMJ 349:g5991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5991

He M, Xiang F, Zeng Y et al (2015) Effect of time spent outdoors at school on the development of myopia among children in China: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314(11):1142–1148. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10803

Whitmore WG (1992) Congenital and developmental myopia. Eye 6(4):361–365. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1992.74

Cochrane GM, du Toit R, Le Mesurier RT (2010) Management of refractive errors. BMJ 340:c1711. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c1711

Harb EN, Wildsoet CF (2019) Origins of refractive errors: environmental and genetic factors. Annu Rev Vis Sci 5:47–72. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-vision-091718-015027

Schaefer-Graf U, Napoli A, Nolan CJ (2018) Diabetes in pregnancy: a new decade of challenges ahead. Diabetologia 61(5):1012–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4545-y

American Diabetes Association (2018) 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 41(Suppl 1):S137–s143. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-S013

Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Magliano DJ, Bennett PH (2016) Diabetes mellitus statistics on prevalence and mortality: facts and fallacies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12(10):616–622. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.105

Shi Y, Vanhoutte PM (2017) Macro- and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. J Diabetes 9(5):434–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12521

Wimmer RA, Leopoldi A, Aichinger M et al (2019) Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature 565(7740):505–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0858-8

Warmke N, Griffin KJ, Cubbon RM (2016) Pericytes in diabetes-associated vascular disease. J Diabetes Complicat 30(8):1643–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.08.005

Kaul P, Bowker SL, Savu A, Yeung RO, Donovan LE, Ryan EA (2019) Association between maternal diabetes, being large for gestational age and breast-feeding on being overweight or obese in childhood. Diabetologia 62(2):249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4758-0

Yu Y, Arah OA, Liew Z et al (2019) Maternal diabetes during pregnancy and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring: population based cohort study with 40 years of follow-up. BMJ 367:l6398. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6398

Cunha-vaz JG (1997) The blood-ocular barriers: past, present, and future. Doc Ophthalmol 93(1):149–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02569055

Kastelan S, Gverovic-Antunica A, Pelcic G, Gotovac M, Markovic I, Kasun B (2018) Refractive changes associated with diabetes mellitus. Semin Ophthalmol 33(7–8):838–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/08820538.2018.1519582

Susa JB, Neave C, Sehgal P, Singer DB, Zeller WP, Schwartz R (1984) Chronic hyperinsulinemia in the fetal rhesus monkey: effects of physiologic hyperinsulinemia on fetal growth and composition. Diabetes 33(7):656. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.33.7.656

Alvarez-Bulnes O, Mones-Llivina A, Cavero-Roig L et al (2020) Ophthalmic pathology in the offspring of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Matern Child Health J 24(4):524–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02887-6

Goncu T, Cakmak A, Akal A, Cakmak S (2015) Comparison of refractive error and central corneal thickness in neonates of diabetic and healthy mothers. Eur J Ophthalmol 25(5):396–399. https://doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000601

Pirola L, Balcerczyk A, Okabe J, El-Osta A (2010) Epigenetic phenomena linked to diabetic complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 6(12):665–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2010.188

Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegard A, Olsen J, Langhoff-Roos J (2018) The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol 33(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0356-1

Carstensen B, Kristensen JK, Ottosen P, Borch-Johnsen K, Steering Group of the National Diabetes R (2008) The Danish National Diabetes Register: trends in incidence, prevalence and mortality. Diabetologia 51(12):2187–2196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1156-z

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl):30–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811401482

Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J (2011) The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl):38–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810394717

Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC (2011) Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl):95–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811408483

Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP (2016) Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation 133(6):601–609. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719

Yu Y, Cnattingius S, Olsen J et al (2017) Prenatal maternal bereavement and mortality in the first decades of life: a nationwide cohort study from Denmark and Sweden. Psychol Med 47(3):389–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171600266X

Watt T, Robertson K, Jacobs RJ (2015) Refractive error, binocular vision and accommodation of children with Down syndrome. Clin Exp Optom 98(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12232

Nielsen GL, Welinder L, Berg Johansen M (2017) Mortality and morbidity in offspring of mothers with diabetes compared with a population group: a Danish cohort study with 8-35 years of follow-up. Diabet Med 34(7):938–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13312

Thompson CA, Arah OA (2014) Selection bias modeling using observed data augmented with imputed record-level probabilities. Ann Epidemiol 24(10):747–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.014

Liew Z, Olsen J, Cui X, Ritz B, Arah OA (2015) Bias from conditioning on live birth in pregnancy cohorts: an illustration based on neurodevelopment in children after prenatal exposure to organic pollutants. Int J Epidemiol 44(1):345–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu249

Said G (2007) Diabetic neuropathy--a review. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 3(6):331–340. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0504

Montes-Mico R (2007) Role of the tear film in the optical quality of the human eye. J Cataract Refract Surg 33(9):1631–1635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.019

Gabbay KH (1973) The sorbitol pathway and the complications of diabetes. N Engl J Med 288(16):831–836. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197304192881609

Zhang SJ, Li YF, Tan RR et al (2016) A new gestational diabetes mellitus model: hyperglycemia-induced eye malformation via inhibition of Pax6 in the chick embryo. Dis Model Mech 9(2):177–186. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.022012

Hua R, Qu L, Ma B, Yang P, Sun H, Liu L (2019) Diabetic optic neuropathy and its risk factors in Chinese patients with diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60(10):3514–3519. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.19-26825

Patel HR, Margo CE (2017) Pathology of ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141(1):162–166. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2016-0027-RS

Landau K, Bajka JD, Kirchschläger BM (1998) Topless optic disks in children of mothers with type I diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol 125(5):605–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00016-6

Tariq YM, Samarawickrama C, Li H, Huynh SC, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P (2010) Retinal thickness in the offspring of diabetic pregnancies. Am J Ophthalmol 150(6):883–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2010.06.036

Weiss AH, Ross EA (1992) Axial myopia in eyes with optic nerve hypoplasia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 230(4):372–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00165948

Ringholm L, Damm P, Mathiesen ER (2019) Improving pregnancy outcomes in women with diabetes mellitus: modern management. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15(7):406–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0197-3

McBrien NA, Barnes DA (1984) A review and evaluation of theories of refractive error development. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 4(3):201–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.1984.tb00357.x

Oyen N, Diaz LJ, Leirgul E et al (2016) Prepregnancy diabetes and offspring risk of congenital heart disease: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation 133(23):2243–2253. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017465

Green A, Sortso C, Jensen PB, Emneus M (2015) Validation of the Danish National Diabetes Register. Clin Epidemiol 7:5–15. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S72768

Frisell T, Oberg S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sjolander A (2012) Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology 23(5):713–720. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230

Mimouni M, Flores V, Shapira Y et al (2018) Correlation between central corneal thickness and myopia. Int Ophthalmol 38(6):2547–2551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-017-0766-1

Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T et al (2017) Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 5(9):e888–e897. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30293-0

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S. Fan (School of Basic Medical Sciences, Nanjing Medical University, China) for designing and drawing the graphical abstract.

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Funding

This study was supported as follows: China National Key Research & Development Program (grant 2016YFC1000200, to HS); the Danish Lundbeck Foundation (grants R232-2016-2462 and R265-2017-4069, to YY); Independent Research Fund Denmark (grants DFF-6110-00019B and 9039-00010B, to JL); the Nordic Cancer Union (grant R275-A15770, to JL); the Karen Elise Jensens Fond (2016, to JL); Novo Nordisk Fonden (grant NNF18OC0052029, to JL); National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81602927, to JD); and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement (891079, to XL). The investigators conducted the research independently. The funders had no role in study design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, JL and YY had full access to the data. JD and YY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JD, JL, XL and YY planned the analysis, researched data and contributed to the discussion. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for submission. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. JD and JL are responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM

(PDF 605 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Du, J., Li, J., Liu, X. et al. Association of maternal diabetes during pregnancy with high refractive error in offspring: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 64, 2466–2477 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05526-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05526-z