Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Bisphenol-A (BPA) is a widespread endocrine-disrupting chemical that has been associated with type 2 diabetes development. Low doses of BPA modify pancreatic beta cell function and induce insulin resistance; some of these effects are mediated via activation of oestrogen receptors α (ERα) and β (ERβ). Here we investigated whether low doses of BPA regulate the expression and function of ion channel subunits involved in beta cell function.

Methods

Microarray gene profiling of isolated islets from vehicle- and BPA-treated (100 μg/kg per day for 4 days) mice was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430.2 Array. Expression level analysis was performed using the normalisation method based on the processing algorithm ‘robust multi-array average’. Whole islets or dispersed islets from C57BL/6J or oestrogen receptor β (ERβ) knockout (Erβ−/−) mice were treated with vehicle or BPA (1 nmol/l) for 48 h. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were used to measure Na+ and K+ currents. mRNA expression was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR.

Results

Microarray analysis showed that BPA modulated the expression of 1440 probe sets (1192 upregulated and 248 downregulated genes). Of these, more than 50 genes, including Scn9a, Kcnb2, Kcnma1 and Kcnip1, encoded important Na+ and K+ channel subunits. These findings were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR in islets from C57BL/6J BPA-treated mice or whole islets treated ex vivo. Electrophysiological measurements showed a decrease in both Na+ and K+ currents in BPA-treated islets. The pharmacological profile indicated that BPA reduced currents mediated by voltage-activated K+ channels (Kv2.1/2.2 channels) and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa1.1 channels), which agrees with BPA’s effects on gene expression. Beta cells from ERβ−/− mice did not present BPA-induced changes, suggesting that ERβ mediates BPA’s effects in pancreatic islets. Finally, BPA increased burst duration, reduced the amplitude of the action potential and enlarged the action potential half-width, leading to alteration in beta cell electrical activity.

Conclusions/interpretation

Our data suggest that BPA modulates the expression and function of Na+ and K+ channels via ERβ in mouse pancreatic islets. Furthermore, BPA alters beta cell electrical activity. Altogether, these BPA-induced changes in beta cells might play a role in the diabetogenic action of BPA described in animal models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic beta cells play a major role in glucose homeostasis because they biosynthesise and release insulin, a key hormone in blood glucose regulation. Decreased insulin release in response to glucose results in chronic hyperglycaemia, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, a metabolic disease that affects over 400 million people around the world [1].

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) from pancreatic beta cells is controlled by electrical activity. In the absence of stimulatory glucose concentrations, beta cells maintain a hyperpolarised membrane potential due to the high activity of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel (KATP channel). Upon glucose stimulation, KATP channel activity decreases due to the rise in the ATP : ADP ratio. This reduction in activity increases membrane input resistance and, consequently, small depolarising currents produce important changes in the membrane potential, generating an oscillatory (bursting) electrical activity that alternates between a hyperpolarised silent phase and a depolarised phase with action potentials [2,3,4]. This bursting pattern of electrical activity induces an oscillatory pattern of intracellular Ca2+ concentration [5] and exocytosis of insulin-containing vesicles [6]. In mouse beta cells, the depolarisation phase of the action potential depends on the activation of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, while the repolarisation phase depends on currents generated by delayed rectifying voltage-activated K+ channels (Kv channels) Kv2.1/2.2 [7,8,9] and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa1.1 channels) [10]. Mouse beta cells express the voltage-activated Na+ channels (Nav channels) Nav1.3 and Nav1.7. Nav1.3 participates in the depolarisation of the action potential and affects insulin secretion [11]; Nav1.7 does not participate in insulin release, yet it might play a role in insulin production [12] and beta cell survival [13]. The repolarisation phase between bursts of action potential is due to small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa2.3 channels) [6, 14, 15].

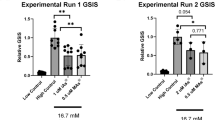

Type 2 diabetes results from gene–environment interactions over time. Genetic alterations in the expression of voltage-activated channels have important consequences for beta cell function and the development of type 2 diabetes [6, 14]. Additionally, animal studies have shown that exposure to bisphenol-A (BPA) alters beta cell function and induces insulin resistance [16,17,18,19]. BPA is found in the urine of 93% of USA citizens [20] and its concentrations in human serum varies between 1 and 25 nmol/l, depending on sex, age and geographical regions, among other factors [21]. BPA has been added by the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) to the candidate list of substances of very high concern due to its endocrine-disrupting properties [22]. In beta cells, low concentrations of BPA (e.g. 1 nmol/l, in vitro) trigger extranuclear-initiated actions via oestrogen receptors α (ERα) and β (ERβ). Within a few minutes, BPA blocks KATP channels via ERβ and potentiates GSIS [19]. Longer in vitro BPA treatments (up to 48 h) upregulate insulin mRNA expression and increase insulin content as well as GSIS in an ERα-dependent manner [17]. Recent work demonstrated that BPA treatment for 48 h downregulated the voltage-activated Ca2+ channel Cav2.3 in an ERβ-dependent manner, leading to decreased amplitude of action potential and diminished exocytosis in the absence of stimulatory glucose levels. Surprisingly, GSIS was still enhanced by BPA treatment [23].

Here, we investigated whether BPA modulated the expression and activity of ion channel subunits in pancreatic islets. This study may help us to understand the regulation of GSIS by this common endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC).

Methods

Chemical substances and animals

The chemical substances used herein are described in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) Methods. Adult male mice, OF1 (11 weeks old; Charles River, Barcelona, Spain) for in vivo treatment (shown in Fig. 1) and C57BL/6J (10–14 weeks old; Envigo, Barcelona, Spain) for the rest of the experiments, were kept under standard housing conditions (12 h light–dark cycle, food ad libitum) in polypropylene veterinary cages. Mice with knockout of the Erβ gene (also known as Esr2) (Erβ−/− mice), supplied by Jan-Åke Gustafsson’s laboratory, were generated as previously described [24]. Wild-type littermates and Erβ−/− mice were obtained from the same supplier and colony. Animals were randomly assigned before BPA treatment. Experimental procedures were carried out according to the Spanish Royal Decree 1201/2005 and the European Community Council directive 2010/63/EU. All methods used herein were approved by the Ethics Committee from Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (Alicante, Spain) (protocols ID: UMH-IB-AN-01–14 and UMH-IB-AN-02-14).

Microarray analysis of islets from mice treated with vehicle (control) or BPA 100 μg/kg per day for 4 days. (a) Dendrogram and hierarchical clustering heat map of gene subsets with similar expression patterns using the open-source data analysis Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) software package, between control and BPA-treated islets (3 replicates each). Genes are grouped together and are connected by a series of branches (clustering tree or dendrogram) according to the average linkage method (cluster-to-cluster distance is defined as the average distance between all members of one cluster and all members of another cluster) using the Euclidean distance (distance threshold = 3.26) as a measure of similarity. The rows in the heat map represent cluster genes and their measurements, while columns represent different experimental conditions; the scales were assessed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) algorithm, which associates the similarity between the samples (top right scale: 0, 0.45 and 18.9) and the genes (top left scale: 0, 6.28 and 12.57). The coloured support boxes to the right highlight clusters (1 to 7). The scaled expression value, denoted as the row z-score, is plotted in yellow–blue colour scale with blue indicating decreased expression (low), black indicating unchanged expression and yellow indicating increased expression (high). Expression data are shown for genes with log2 (fold change) differences of expression >0.58 (p<0.05). (b) Expanded view of hierarchical clustering heat maps for pancreatic genes of interest detected within clusters 2 (blue box), 3 (green box) and 7 (black box), showing the expression signatures of gene candidates in PBA-treated mice, as determined by applying k means clustering algorithms (k=10; maximum iterations 50). (c) Scatter plot with log2 fold change of DEGs between control and BPA-treated islets (p<0.05). Selected upregulated and downregulated genes in islets are highlighted in blue (indicating decreased expression) and in yellow (indicating increased expression) (n=3 mice per group). (d) The predicted Biological Process GO terms identified to be upregulated (n=18 terms) or downregulated (n=10 terms) in BPA-treated islets. The p value was used to determine the significance of enrichment or overrepresentation of terms for each annotation. The ranking score was obtained using enrichment −log10(p value) from the predicted target genes. The x-axis represents score and the y-axis represents the top enriched signalling pathways

BPA treatment

For in vivo experiments (three to seven mice per condition), BPA was dissolved in tocopherol-stripped corn oil; a total of 100 μg/kg per day (two injections of 50 μg/kg per day) was administered subcutaneously for 4 days. The same volume of tocopherol-stripped corn oil (100 μl) was used as vehicle. Sixteen hours after the last injection, mice were killed and islets were isolated. For ex vivo experiments, BPA was prepared each week by dissolution in DMSO (used as vehicle).

Culture of islets and dispersed islet cells

Pancreatic islets were isolated using collagenase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) as described [25]. For some experiments, pancreatic islets were dispersed into isolated cells [26]. Before any treatment, whole islets and dispersed cells were cultured for 48 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. See ESM Methods for further details.

Microarray analysis

Islets from three BPA-treated OF1 male mice were isolated. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) and 1 μg was used to obtain the gene expression profile of each sample. Biotinylated cRNA (10 μg) prepared from total RNA was hybridised on an Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Microarrays were scanned using GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and were processed with GeneChip Operating System (GCOS) 1.4.0.036 (Affymetrix) to generate the CEL file expression data. All analyses were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Statistical data analyses were performed using the Limma package (affylmGUI interface) of the R Bioconductor project (http://www.bioconductor.org; R package version 2.7.0). Genes were considered significantly upregulated or downregulated when their expression values were fold change (linear) >1.5 and p value <0.05. Functional annotation and biological term enrichment were performed using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID 6.8; https://david.ncifcrf.gov). Enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org) Biological Process terms were considered as statistically significant when p < 0.05 (Genomic core facility of CABIMER) [27, 28]. Dendrograms and hierarchical clustering heat maps were generated using the open-source data analysis Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) software package version 4.0, available at: http://mev.tm4.org/.

Na+ and K+ currents

In Figs 2 and 4 and ESM Figs 2, 4 and 5, the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration was used, while in Fig. 5 and ESM Fig. 1 we used the perforated patch whole-cell recording mode. Data were acquired using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, San Jose, CA, USA). All experiments were performed at 32–34°C. See Ref. [23] and ESM Methods for further details.

BPA inhibits Na+ currents in mouse pancreatic beta cells. (a) mRNA expression of Scn9a in islets from mice treated with vehicle (control; grey bars) or BPA 100 μg/kg per day (white bars) for four days. (b) Scn9a mRNA expression in islets treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; light grey bars) or BPA 1 nmol/l (white bars) for 48 h. (c, d) Scn9a mRNA expression in islets from wild-type (c) and Erβ−/− (d) mice treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; light grey bars) or BPA 1 nmol/l (white bars) for 48 h. mRNA expression in (a–d) was measured by qRT-PCR and normalised to the housekeeping gene Hprt1 and is shown as fold vs control. Data are shown as means ± SEM of: six or seven (a), seven or eight (b), five or six (c) or eight (d) independent experiments: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01 (Student’s t test). (e) Representative recordings of Na+ and Ca2+ currents in response to a depolarising voltage pulse (−70 mV to +10 mV; 5 ms duration) after conditioning prepulses (from −150 mV to 0 mV) (inset) in dispersed cells treated with vehicle (control) or BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h. Na+ currents are clearly distinguishable from Ca2+ currents by their faster activation and inactivation kinetics (indicated by arrows). (f, g) Relationship between Na+ current density (Na+ currents in pA normalised to the cell capacitance in pF) and the voltage of the prepulses in dispersed cells from wild-type (WT) (f) and Erβ−/− (g) mice treated ex vivo with vehicle (control, n=9 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (n=12 beta cells) for 48 h. Data are shown as means ± SEM of the number of cells recorded. These cells were isolated from five (f) or three (g) mice on at least three different days: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01 vs control at the same Vh (Student’s t test). Vh, holding potential

Real-time PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplification reactions were performed as described [23]. Values were analysed with CFX Manager Version 1.6 (Bio-Rad) and expressed as the relative expression in respect of control values (\( {2}^{-\varDelta \varDelta {\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{t}}} \)) [29]. Hprt was used as housekeeping gene. Similar results were obtained when Gapdh was used as housekeeping gene (data not shown). The primers used herein are listed in ESM Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Experimenters were not blind to group assignment and outcome assessment. GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for most statistical analyses. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. To assess differences between groups, we used two-tailed Student’s t test or ANOVA when appropriate. For nonparametric data we used Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA tests (followed by Dunn’s test), depending on the experimental groups involved in the comparison. Except for the microarray analysis (see above), a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BPA regulates ion channel subunits expression in mouse islets

To study the effects of BPA on beta cell gene expression, we treated adult OF1 male mice with vehicle (control; n = 3) or BPA 100 μg/kg per day (n = 3) for 4 days. Afterwards, we performed a microarray analysis of islets obtained from both groups. Hierarchical clustering analysis of differentially expressed genes showed a clear separation between control and BPA-treated islets (Fig. 1a). In vivo BPA treatment significantly modified the expression of 1440 probe sets, of which 1192 were upregulated and 248 downregulated. Overall, our analysis identified 50 genes related to ion channel subunits within clusters 2, 3 and 7, including Cacn2d1, Kcnma1 and Scn9a (Fig. 1b,c and Table 1). Based on these observations, we performed a DAVID analysis to identify potentially enriched biological processes among the putative target genes of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using GO terms (http://www.geneontology.org), and to identify the related pathways using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg; Release 89.0, January 1, 2019). Gene ontology enrichment analysis revealed several DEGs related to ion channel subunit regulation (Fig. 1c). Besides, based on these DEGs, 18 upregulated and ten downregulated signalling pathways were identified in BPA-treated islets predicted to be mainly related to ion channels (Fig. 1d).

BPA reduces the expression of Na+ channel subunits and Na+ currents via ERβ

The Nav1.7 channel is the most abundant Na+ channel in mouse beta cells, contributing to approximately 85% of the Na+ current [30]. Our microarray analysis indicated that expression of the Nav1.7 channel, encoded by Scn9a, was downregulated upon BPA exposure (Fig. 1, Table 1). To confirm these data, we measured Scn9a expression in islets from C57BL/6J BPA-treated mice (100 μg/kg per day for 4 days) or mouse islets treated ex vivo (BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h). We observed that BPA treatment diminished Scn9a expression in mouse islets in vivo and ex vivo (Fig. 2a,b). To assess whether this downregulation affected Na+ currents in beta cells, we recorded the currents using perforated patch-clamp whole-cell recordings in response to a depolarising pulse from −70 mV to 10 mV, preceded by a prepulse from −150 mV to 0 mV to remove inactivation of Nav1.7 channel currents [11] (ESM Fig. 1). As expected, BPA treatment significantly reduced voltage-activated Na+ currents, possibly due to Scn9a downregulation. Of note, expression of Scn3a, which encodes the Nav1.3 channel, was not modified by BPA treatment (Table 1). As a positive control of the oestrogenic effects of BPA, we measured Na+ currents in control and 17β-oestradiol-treated beta cells. The 17β-oestradiol-treated beta cells presented reduced voltage-activated Na+ currents when compared with control beta cells (ESM Fig. 2a,b).

Our recent findings suggest that, in pancreatic islets, BPA 1 nmol/l downregulates the voltage-activated Ca2+ channel Cav2.3 and decreases the R-type Ca2+ current in an ERβ-dependent manner [23]. To evaluate whether ERβ played a role in the regulation of Na+ currents upon BPA exposure, we treated islets from wild-type and Erβ−/− mice with BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h. While BPA decreased Scn9a expression (Fig. 2c) and Na+ currents (Fig. 2e,f) in wild-type mouse islets, its effects on Scn9a expression (Fig. 2d) and Na+ currents (Fig. 2g) were abolished in islets from Erβ−/− mice. Moreover, treatment with the ERβ agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN, 1 nmol/l) decreased Na+ currents (ESM Fig. 2c), which supports a role for ERβ in the modulation of Na+ currents.

BPA modulates the expression of different K+ channel subunits

As demonstrated by our microarray analysis, BPA modulated the expression of several genes related to K+ channels (see Table 1). To confirm these changes, we measured Kcnab2, Kcnc4 and Kcnj12 mRNA expression in islets from BPA-treated mice (100 μg/kg per day for 4 days) or mouse islets treated ex vivo (BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h) (ESM Fig. 3). As observed in the microarray analysis, Kcnab2 and Kcnc4 expression was increased (ESM Fig. 2a,b,d,e), while Kcnj12 was downregulated by BPA treatment (ESM Fig. 3c,f).

BPA reduces the expression of K+ channel subunits and K+ currents via ERβ

The voltage-activated K+ channels Kv2.1 (encoded by Kcnb1) and Kv2.2 (Kcnb2), as well as the KCa1.1 channel (Kcnma1), are major contributors of the repolarisation phase of the action potential in beta cells [10, 15, 31]. Furthermore, K+ channel-interacting protein 1 (encoded by Kcnip) seems to be important for GSIS [32]. We assessed whether BPA treatment modulated the expression of these channel subunits and observed that, except for Kcnb1, mRNA expression of Kcnb2, Kcnma1 and Kcnip1 was decreased by BPA treatment in vivo (Fig. 3a–d) and ex vivo (Fig. 3e–h). BPA’s effects on Kcnb2, Kcnip1 and Kcnma1 mRNA expression was abrogated in islets from Erβ−/− mice (Fig. 3m–p) when compared with wild-type littermate control mice (Fig. 3i–l).

BPA inhibits expression of K+ channel subunits in mouse pancreatic beta cells. (a–d) mRNA expression of Kcnb1 (a), Kcnb2 (b), Kcnma1 (c) and Kcnip1 (d) in islets from mice treated with vehicle (control; grey bars) or BPA 100 μg/kg per day (white bars) for 4 days. (e–h) mRNA expression of Kcnb1 (e), Kcnb2 (f), Kcnma1 (g) and Kcnip1 (h) in whole mouse islets treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; light grey bars) or BPA 1 nmol/l (white bars) for 48 h. (i–p) mRNA expression of Kcnb1 (i, m), Kcnb2 (j, n), Kcnma1 (k, o) and Kcnip1 (l, p) in islets from wild-type (i–l) and Erβ−/− (m–p) mice treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; light grey bars) or BPA 1 nmol/l (white bars) for 48 h. mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR and normalised to the housekeeping gene Hprt1 and is shown as fold vs control. Data are shown as means ± SEM of: six to seven (a–d), nine (e–h), four to six (i–l) or eight (m–p) independent experiments: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 (Student’s t test)

To determine whether BPA-induced downregulation of these K+ channels would be reflected in the K+ efflux, we recorded K+ currents in beta cells from wild-type and Erβ−/− mice using the patch-clamp technique in the whole-cell configuration. Figure 4a shows the recordings of the K+ currents in response to depolarising voltage pulses from −60 mV to +80 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV in cells from wild-type mice. When compared with vehicle-treated cells, currents were significantly smaller in BPA-treated cells starting from 0 mV, which is about the peak of glucose-induced action potentials (Fig. 4b). Measurements of the whole-cell K+ currents showed that BPA had no effect on peak current density in beta cells from Erβ−/− mice (Fig. 4c). We further assessed whether ERβ was indeed involved in the regulation of K+ currents by measuring K+ currents in control and DPN-treated cells. We observed that DPN treatment decreased K+ currents, supporting a role for ERβ in the modulation of K+ currents (ESM Fig. 4).

BPA inhibits K+ currents in mouse pancreatic beta cells. (a) Representative recordings of K+ currents in response to depolarising voltage pulses (−60 mV to +80 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV, 500 ms duration [inset]) in isolated beta cells treated with vehicle (control) or BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h. (b, c) Relationship between K+ current density (K+ currents in pA normalised to the cell capacitance in pF) and the voltage of the pulses in dispersed cells from wild-type (WT) (b) and Erβ−/− (c) mice treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; n=15 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (n=18 beta cells) for 48 h. (d) Relationship between K+ current density (K+ currents in pA normalised to the cell capacitance in pF) and the voltage of the pulses in dispersed cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; n=11 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (n = 11 beta cells) for 48 h in the presence of IbTX (100 nmol/l) to block KCa1.1 currents. (e) The same experiment as in (d) but in the presence of ScTx (100 nmol/l) to block Kv2.1/2.2 currents. Data are shown as means ± SEM of the number of cells recorded. Cells were isolated from five (b), two (c), or four (d, e) mice on at least three different days: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 vs control at the same Vpulse (Student’s t test)

K+ currents result from the passage of K+ through several types of voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels whose expression was changed by BPA exposure (Figs 1 and 3, Table 1, ESM Fig. 2). To determine which K+-channel subtypes were altered by BPA exposure, we measured K+ current in mouse beta cells in the absence or presence of iberiotoxin (IbTx, a specific blocker of KCa1.1 channels), or stromatoxin-1 (ScTx1, a selective inhibitor of the homotetrameric Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 channels). In the presence of 100 nmol/l IbTx, the peak current density was decreased by BPA, although to a lesser extent than in the absence of the blocker (Fig. 4d). Similarly, BPA diminished K+ currents even in the presence of ScTx1 100 nmol/l (Fig. 4e). These results show that BPA reduces both Kv2.1/2.2 and KCa1.1 channel subtypes, consistent with the BPA-induced downregulation of Kcnb2 and Kcnma1. To evaluate whether the effects of BPA on K+ currents were due to its oestrogenic activity, we measured K+ currents in control and 17β-oestradiol-treated cells. Surprisingly, contrary to its effect on Na+ currents (ESM Fig. 2a,b), 17β-oestradiol did not modify K+ currents (ESM Fig. 5).

BPA alters electrical activity

The electrical activity in response to an increase in the external glucose concentration (from 0 mmol/l to 11 mmol/l) was recorded from dissociated beta cells using the perforated patch-clamp technique (see details in ESM Fig. 6). Compared with vehicle-treated control beta cells (Fig. 5a), BPA treatment altered the characteristic single burst of dissociated beta cells (Fig. 5b). The burst duration, measured as the time of action potential firing (Fig. 5c) or as the percentage of time firing action potentials in the burst (Fig. 5d), was increased by BPA. As previously shown, a reduction in the amplitude of action potentials was due to decreased Ca2+ currents after BPA-induced Cav2.3 downregulation. Here we show that BPA reduced the amplitude of the action potential after hyperpolarisation (Fig. 5e,f) and enlarged the half-width of the action potential (Fig. 5g), indicating that BPA induced a reduction in K+ currents as reported above. Furthermore, because of the changes in the action potential waveform, the AUC of the action potential also diminished (Fig. 5h).

BPA alters glucose-induced electrical activity in mouse pancreatic beta cells. (a, b) Response of pancreatic beta cell electrical activity to a stimulatory glucose level (11 mmol/l), recorded using the perforated patch-clamp technique in dispersed cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control, n=15 beta cells) (a) or BPA 1 nmol/l (n=18 beta cells) (b) for 48 h. (c) Burst duration at 11 mmol/l glucose in dispersed cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control, n=7 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (n=7 beta cells) for 48 h. (d) The same experiment as in (c) but expressed as percentage of burst duration vs time depolarised at 11 mmol/l glucose. Data in (c,d) are shown as the means ± SEM of the number of cells recorded. Cells were isolated from seven mice on at least three different days: **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 (Student’s t test). (e) Superimposed representative action potentials at 11 mmol/l glucose in dispersed beta cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control) or BPA 1 nmol/l for 48 h. (f) After-hyperpolarisation (AHP) amplitude following action potentials in dispersed beta cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; 1600 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (1780 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) for 48 h. (g) Action potential half-width in dispersed beta cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; 1452 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (1342 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) for 48 h. (h) AUC of action potential area in dispersed beta cells treated ex vivo with vehicle (control; 1780 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) or BPA 1 nmol/l (1780 action potentials from n=11 beta cells) for 48 h. Data in (f–h) are shown as the means ± SEM of the number of cells recorded. These cells were isolated from five mice on at least three different days: ***p≤0.001 (Student’s t test)

Discussion

Pancreatic beta cells encode information with electrical signals. In response to glucose, beta cells produce bursts of action potentials, generated by the activation of ion channels expressed in their membrane, which ultimately stimulate insulin secretion. Thus, any alteration in the expression and/or activation of ion channels in beta cells leads to alteration of insulin secretion and disturbance of glucose homeostasis. Our findings indicate that environmentally relevant doses of BPA alter ion channel expression in beta cells in an ERβ-dependent manner. Consequently, whole-cell Ca2+ [23], K+ and Na+ currents were reduced, altering the shape of action potentials and modifying beta cell electrical activity. Studies in humans and animal models suggest that anomalies in beta cell function, including alterations of beta cell electrical activity, play important roles in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes [33, 34]. Thus, the changes in the expression and activity of ion channels described herein might contribute to the diabetogenic action of BPA observed in animal models [16, 35, 36] and in epidemiological human studies [37,38,39].

Microarray analysis indicated that the expression of more than 50 genes encoding ion channel subunits were either upregulated or downregulated in response to BPA treatment in vivo. It has been shown that the treatment used here induces insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in the non-fasted state [16, 18]. This BPA dose can be considered low as it is only twice the ‘reference dose’ (50 μg/kg per day) believed by the US Environmental Protection Agency to be safe over a lifetime. An oral dose of BPA equal to this reference dose rapidly altered GSIS, decreasing GSIS second phase in obese individuals (mean BMI 31 kg/m2) [40]. In 2015, the European Union reduced the tolerable BPA daily intake to 4 μg/kg [41].

The changes in gene expression observed in vivo were reproduced in primary cultured beta cells treated with BPA 1 nmol/l. Of note, this BPA concentration is similar to that found in human serum [20]. The fact that BPA alters ion channel expression in primary cells indicates that BPA acts directly on beta cells and, therefore, the changes observed in vivo are not the result of islet adaptation to counteract insulin resistance. Nonetheless, we cannot completely discount some indirect effects of BPA in our in vivo results.

Voltage-activated K+ channels are responsible for the outward currents underlying the falling phase of the action potential [42]. Kcnb2, encoding the Kv2.2 channel, is involved in the mouse beta cell electrical activity and its inhibition impairs GSIS [43]. Here, Kcnb2 expression was decreased by BPA both in vivo and ex vivo. The related channel Kv2.1 (encoded by Kcnb1) is responsible for most of the outward current during action potential repolarisation and its ablation increases insulin release [31, 44]. However, the expression of Kcnb1 did not significantly change upon BPA exposure. BPA treatment also decreased expression of Kcnip1, which encodes the major β-subunit of Kv channels expressed in mouse beta cells [32]. Although the role of Kcnip1 is poorly understood, silencing of Kcnip1 potentiates GSIS without altering insulin transcription in MIN6N8 beta cells [32].

Our patch-clamp experiments showed that BPA reduced K+ outward currents. To study BPA’s effects on Kv channels in isolation, we blocked the KCa1.1 channel (which would be activated with the voltage-clamp protocol employed) with iberiotoxin. We observed a reduction in BPA-induced voltage-activated K+ currents. However, we cannot differentiate between the closely related Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 channels in these experiments. The BPA-induced decrease in K+ current could be caused by the diminished expression of Kv2.2 channel subunits, although we cannot rule out a BPA-elicited change in the biophysical properties of some K+ channels, particularly the Kv2.1 channel whose gene expression remained unchanged.

In addition to the effect of BPA in voltage-activated Kv2.1/Kv2.2 channels, we investigated whether BPA affected KCa1.1 channels, which are critical in action potential shaping [6]. For this purpose, we employed ScTx1 as a blocker of Kv2.1/Kv2.2 channels. Our results indicate that BPA decreased a fraction of the large outward current that was resistant to ScTx1 and hence carried by KCa1.1 channels, indicating that KCa1.1 channels are sensitive to BPA. This effect could be attributed to the BPA-induced downregulation of Kcnma1, which encodes the α1 subunit of KCa1.1 channels. KCa1.1 channels are Ca2+- and voltage-dependent channels that, in mouse beta cells, play a part mostly in cells with large Ca2+ currents, in which KCa1.1 channel blockade increased spike amplitude and potentiated GSIS [10].

Changes in the expression of Kv and KCa1.1 channel subunits could explain the change in the shape of action potentials and the alteration of the electrical activity pattern induced by BPA exposure. The decreased activity of Cav2.3 channels in the presence of 1 nmol/l BPA [23] could be responsible for the diminished amplitude of the action potential. A decrease in Ca2+ entry would contribute to a diminished activation of KCa1.1 channels that, together with downregulation of KCa1.1 and Kv2.2 channels, results in wider action potentials. Given the role of K+ current in beta cell electrical activity [6], this effect of BPA exposure should cause longer bursts of electrical activity (present data) and may explain, at least partially, the enhanced GSIS already described in BPA-exposed beta cells [16, 17, 23].

Mouse beta cells express two main types of Na+ channels, Nav1.3 and Nav1.7, whose roles are less understood compared with Ca2+ and K+ channels. The Nav1.3 channel is responsible for only a small part of the total Na+ current and it may play a role in the depolarisation of the action potential [30]. Alternatively, the Nav1.7 channel, encoded by Scn9a, corresponds to 85% of the Na+ current [30], although its role is yet to be unveiled as the Nav1.7 channel is inactivated at physiological membrane potentials. While no alterations in GSIS are observed in Scn9a−/− mice, these mice present higher insulin content relative to wild-type counterparts [12]. Furthermore, Nav1.7 channel inhibition increases both Ins1 and Ins2 mRNA expression [12]. These data suggest that Nav1.7 channels may be associated with insulin biosynthesis. It has been shown that BPA augments insulin content through an ERα/ERK pathway [17]. However, it remains to be determined whether the BPA-induced Snc9a downregulation observed in the present study is associated with the increase in insulin content observed in BPA-treated beta cells.

Of note, our experiments using beta cells from Erβ−/− mice indicated that BPA decreased Scn9a, Kcnb2 and Kcnma1 expression, as well as Na+ and K+ currents, in an ERβ-dependent manner. The use of a global Erβ knockout may represent a handicap in our study as the ERβ receptor is important for other tissues involved in glucose homeostasis. Hence, it might be suggested that the absence of ERβ could indirectly affect beta cells in vivo. Nevertheless, this in vivo component seems unlikely in our model, at least considering the ion channels studied herein. If we carefully analyse the current–voltage curves for beta cells from wild-type and Erβ−/− mice, we can see that they are identical. Moreover, our data with DPN, an ERβ agonist, fully reproduced BPA’s effects on Na+ and K+ currents, reinforcing the role played by ERβ in the BPA-induced changes identified in beta cells. Of note, our findings do not rule out the involvement of other oestrogen receptors, such as ERα and G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor 1 (GPER), in the pathway activated by BPA.

The changes in the expression of ion channel subunits, ion channel-mediated currents and electrical activity presented here suggest that low doses of BPA alter beta cell function via ERβ. These effects of BPA could be responsible, at least in part, for the previously described increase in GSIS in vivo and ex vivo [16, 17, 23]. Moreover, Nav1.7 channel downregulation opens the possibility of a new regulatory pathway activated by ERβ to regulate insulin biosynthesis. As the BPA concentration used herein was similar to that found in the human population, these results reinforce the likely diabetogenic action of BPA.

Thus, our present results establish a mechanistic link to explain the BPA-induced enhancement in GSIS, placing the main channels involved in beta cell electrical activity as key targets of a diabetogenic EDC (Fig. 6). Moreover, understanding how BPA regulates the shape of action potentials in beta cells is important for revealing the mechanisms by which this EDC acts in other excitable cells, including neurons and cardiac, skeletal and smooth muscle cells. This may be relevant to explain the actions of BPA on the nervous system and its effects in cardiovascular disease [45].

Stimulus–secretion coupling model showing Ca2+ and K+ channels downregulated by BPA in mouse pancreatic beta cells. (a) The main ion channels involved in glucose-induced electrical activity in mouse pancreatic beta cells. The KATP channel is responsible for the resting membrane potential and the voltage-gated Cav1.2, Cav2.3, Kv2.1, Kv2.2 and KCa1.1 channels remain closed in the absence of stimuli. BPA downregulates the expression and the currents mediated by Cav2.3 (see [23]), Kv2.2, and KCa1.1 channels. (b) Upon an increase in extracellular glucose levels, glucose enters the cell and is metabolised, which causes a rise in the ATP:ADP ratio. Subsequently, KATP channels are closed, leading to membrane depolarisation and opening of the voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels. The subsequent Ca2+ influx triggers insulin release. BPA-induced downregulation of Cav2.3, Kv2.2 and KCa1.1 channels helps to explain the modified shape of the action potential elicited by BPA (Fig. 5e), which culminates in increased insulin release. Note that the Na+ channels Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 are not included because their role in the stimulus–secretion coupling model is still unclear. GK, glucokinase; Vm, membrane potential

Data availability

The data presented in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE126297 [46].

Abbreviations

- BPA:

-

Bisphenol-A

- Cav :

-

Voltage-activated Ca+ channel

- DAVID:

-

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- DPN:

-

Diarylpropionitrile

- EDC:

-

Endocrine-disrupting chemical

- ERα:

-

Oestrogen receptor α

- ERβ:

-

Oestrogen receptor β

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- GSIS:

-

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- IbTx:

-

Iberiotoxin

- KATP channel:

-

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- KCa1.1 channel:

-

Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- KCa2.3 channel:

-

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- Kv channel:

-

Voltage-activated K+ channel

- Nav channel:

-

Voltage-activated Na+ channel

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative RT-PCR

- ScTx1:

-

Stromatoxin-1

References

World Health Organization (2018) Diabetes. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed 20 Oct 2018

Ashcroft FM, Harrison DE, Ashcroft SJ (1984) Glucose induces closure of single potassium channels in isolated rat pancreatic β-cells. Nature 312(5993):446–448. https://doi.org/10.1038/312446a0

Dean PM, Matthews EK (1968) Electrical activity in pancreatic islet cells. Nature 219(5152):389–390. https://doi.org/10.1038/219389a0

Dean PM, Matthews EK (1970) Glucose-induced electrical activity in pancreatic islet cells. J Physiol 210(2):255–264. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009207

Santos RM, Rosario LM, Nadal A, Garcia-Sancho J, Soria B, Valdeolmillos M (1991) Widespread synchronous [Ca2+]i oscillations due to bursting electrical activity in single pancreatic islets. Pflugers Arch 418(4):417–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00550880

Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM (2018) Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol Rev 98(1):117–214. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00008.2017

Herrington J, Zhou YP, Bugianesi RM et al (2006) Blockers of the delayed-rectifier potassium current in pancreatic β-cells enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion. Diabetes 55(4):1034–1042. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0788

MacDonald PE, Wheeler MB (2003) Voltage-dependent K+ channels in pancreatic beta cells: role, regulation and potential as therapeutic targets. Diabetologia 46(8):1046–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-003-1159-8

Roe MW, Worley JF 3rd, Mittal AA et al (1996) Expression and function of pancreatic β-cell delayed rectifier K+ channels. Role in stimulus-secretion coupling. J Biol Chem 271(50):32241–32246. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.50.32241

Houamed KM, Sweet IR, Satin LS (2010) BK channels mediate a novel ionic mechanism that regulates glucose-dependent electrical activity and insulin secretion in mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol 588(Pt 18):3511–3523. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184341

Gopel S, Kanno T, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P (1999) Voltage-gated and resting membrane currents recorded from B cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol 521(3):717–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00717.x

Szabat M, Modi H, Ramracheya R et al (2015) High-content screening identifies a role for Na+ channels in insulin production. R Soc Open Sci 2(12):150306. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150306

Yang YH, Vilin YY, Roberge M, Kurata HT, Johnson JD (2014) Multiparameter screening reveals a role for Na+ channels in cytokine-induced β-cell death. Mol Endocrinol 28(3):406–417. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2013-1257

Skelin Klemen M, Dolensek J, Slak Rupnik M, Stozer A (2017) The triggering pathway to insulin secretion: Functional similarities and differences between the human and the mouse beta cells and their translational relevance. Islets 9(6):109–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19382014.2017.1342022

Gopel SO, Kanno T, Barg S et al (1999) Activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels contributes to rhythmic firing of action potentials in mouse pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol 114(6):759–770. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.114.6.759

Alonso-Magdalena P, Morimoto S, Ripoll C, Fuentes E, Nadal A (2006) The estrogenic effect of bisphenol A disrupts pancreatic β-cell function in vivo and induces insulin resistance. Environ Health Perspect 114(1):106–112. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8451

Alonso-Magdalena P, Ropero AB, Carrera MP et al (2008) Pancreatic insulin content regulation by the estrogen receptor ER alpha. PLoS One 3(4):e2069. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002069

Batista TM, Alonso-Magdalena P, Vieira E et al (2012) Short-term treatment with bisphenol-A leads to metabolic abnormalities in adult male mice. PLoS One 7(3):e33814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033814

Soriano S, Alonso-Magdalena P, Garcia-Arevalo M et al (2012) Rapid insulinotropic action of low doses of bisphenol-A on mouse and human islets of Langerhans: role of estrogen receptor beta. PLoS One 7(3):e31109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031109

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL (2008) Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect 116(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10753

Olsen L, Lampa E, Birkholz DA, Lind L, Lind PM (2012) Circulating levels of bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates in an elderly population in Sweden, based on the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 75(1):242–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.09.004

European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2018) Seven new substances added to the Candidate List, entry for bisphenol-A updated. Available from https://echa.europa.eu/es/-/seven-new-substances-added-to-the-candidate-list-entry-for-bisphenol-a-updated-to-reflect-its-endocrine-disrupting-properties-for-the-environment. Accessed 10 Oct 2018

Villar-Pazos S, Martinez-Pinna J, Castellano-Munoz M et al (2017) Molecular mechanisms involved in the non-monotonic effect of bisphenol-a on Ca2+ entry in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Sci Rep 7(1):11770. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11995-3

Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF et al (1998) Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95(26):15677–15682. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677

Nadal A, Soria B (1997) Glucose metabolism regulates cytosolic Ca2+ in the pancreatic β-cell by three different mechanisms. Adv Exp Med Biol 426:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1819-2_33

Valdeolmillos M, Nadal A, Contreras D, Soria B (1992) The relationship between glucose-induced K+ATP channel closure and the rise in [Ca2+]i in single mouse pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol 455(1):173–186. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019295

Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4(1):44–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.211

Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA (2009) Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 37(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn923

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the \( {2}^{-\varDelta \varDelta {\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{t}}} \) method. Methods 25(4):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Zhang Q, Chibalina MV, Bengtsson M et al (2014) Na+ current properties in islet alpha- and beta-cells reflect cell-specific Scn3a and Scn9a expression. J Physiol 592(21):4677–4696. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2014.274209

Jacobson DA, Kuznetsov A, Lopez JP, Kash S, Ammala CE, Philipson LH (2007) Kv2.1 ablation alters glucose-induced islet electrical activity, enhancing insulin secretion. Cell Metab 6(3):229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2007.07.010

Lee HS, Moon S, Yun JH et al (2014) Genome-wide copy number variation study reveals KCNIP1 as a modulator of insulin secretion. Genomics 104(2):113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.05.004

Hiriart M, Velasco M, Larque C, Diaz-Garcia CM (2014) Metabolic syndrome and ionic channels in pancreatic beta cells. Vitam Horm 95:87–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800174-5.00004-1

Kahn SE, Zraika S, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL (2009) The beta cell lesion in type 2 diabetes: there has to be a primary functional abnormality. Diabetologia 52(6):1003–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1321-z

Moon MK, Jeong IK, Jung Oh T et al (2015) Long-term oral exposure to bisphenol A induces glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. J Endocrinol 226(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-14-0714

Nadal A, Alonso-Magdalena P, Soriano S, Quesada I, Ropero AB (2009) The pancreatic β-cell as a target of estrogens and xenoestrogens: implications for blood glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 304(1–2):63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.016

Hong SH, Sung YA, Hong YS et al (2017) Urinary bisphenol A is associated with insulin resistance and obesity in reproductive-aged women. Clin Endocrinol 86(4):506–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13270

Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A et al (2008) Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults. JAMA 300(11):1303–1310. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.11.1303

Wang T, Li M, Chen B et al (2012) Urinary bisphenol A (BPA) concentration associates with obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(2):E223–E227. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-1989

Stahlhut RW, Myers JP, Taylor JA, Nadal A, Dyer JA, Vom Saal FS (2018) Experimental BPA exposure and glucose-stimulated insulin response in adult men and women. J Endocr Soc 2(10):1173–1187. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2018-00151

EFSA (2015) Scientific opinion on bisphenol A. Available from http://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/corporate_publications/files/factsheetbpa150121.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2018

Jan LY, Jan YN (2012) Voltage-gated potassium channels and the diversity of electrical signalling. J Physiol 590(11):2591–2599. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224212

Jensen MV, Haldeman JM, Zhang H et al (2013) Control of voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.2 expression by pyruvate-isocitrate cycling regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 288(32):23128–23140. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.491654

MacDonald PE, Sewing S, Wang J et al (2002) Inhibition of Kv2.1 voltage-dependent K+ channels in pancreatic β-cells enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 277(47):44938–44945. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M205532200

Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE et al (2015) EDC-2: The Endocrine Societyʼs second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr Rev 36(6):E1–E150. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1010

Gene Expression Omnibus (2019) In vivo effects of short-term treatment with Bisphenol A (BPA) on mice pancreatic islets. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE126297. Accessed 10 Sept 2018

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. L. Navarro, S. Ramon and D. Navarro (IBMC/IDiBE, Universitas Miguel Hernández) for their excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) grants BPU2017-86579-R and SAF2014-58335-P (AN) and BFU2016-77125-R (IQ); Generalitat Valenciana PROMETEO II/2015/016 (AN); Grant for Networks of Excellence from MICINN ‘Nuclear Receptors in Cancer, Metabolism and Inflammation’ (NuRCaMeIn) (SAF2017-90604-REDT); Spanish Institute of Health Carlos III grants PI16/00259 (AH), PI17/02104 and RD16/0011/0034 (BS) co-financed by FEDER Funds. LM holds a Juan de la Cierva fellowship from the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (IJCI-2015-24482). CIBERDEM is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. J-AG was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (E-0004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM-P, LM and AN conceived the study. JM-P, LM, AH, JL-B, SS, SV-P, FM and PA-M collected and analysed the data. JM-P, LM, SS, SV-P, PA-M, RSDS, IQ, BS, J-AG, JM-P and AN interpreted the data. JM-P, RSDS and AN drafted the manuscript. AN supervised the study. RSDS, IQ, J-AG critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AH, IQ, BS, J-AG and AN acquired the funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript, and gave consent to publication. AN is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM

(PDF 519 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez-Pinna, J., Marroqui, L., Hmadcha, A. et al. Oestrogen receptor β mediates the actions of bisphenol-A on ion channel expression in mouse pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 62, 1667–1680 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4925-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4925-y