Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Chronic hyperglycaemia in type 1 diabetes affects the structure and functioning of the brain, but the impact of recurrent hypoglycaemia is unclear. Changes in the neurochemical profile have been linked to loss of neuronal function. We therefore aimed to investigate the impact of type 1 diabetes and burden of hypoglycaemia on brain metabolite levels, in which we assumed the burden to be high in individuals with impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (IAH) and low in those with normal awareness of hypoglycaemia (NAH).

Methods

We investigated 13 non-diabetic control participants, 18 individuals with type 1 diabetes and NAH and 13 individuals with type 1 diabetes and IAH. Brain metabolite levels were determined by analysing previously obtained 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy data, measured under hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic conditions.

Results

Brain glutamate levels were higher in participants with diabetes, both with NAH (+15%, p = 0.013) and with IAH (+19%, p = 0.003), compared with control participants. Cerebral glutamate levels correlated with HbA1c levels (r = 0.40; p = 0.03) and correlated inversely (r = −0.36; p = 0.04) with the age at diagnosis of diabetes. Other metabolite levels did not differ between groups, apart from an increase in aspartate in IAH.

Conclusions/interpretation

In conclusion, brain glutamate levels are elevated in people with type 1 diabetes and correlate with glycaemic control and age of disease diagnosis, but not with burden of hypoglycaemia as reflected by IAH. This suggests a potential role for glutamate as an early marker of hyperglycaemia-induced cerebral complications of type 1 diabetes.

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03286816; NCT02146404; NCT02308293

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes has a negative effect on the structure and functioning of the brain [1]. Several studies report on a lower cognitive performance in people with type 1 diabetes compared with non-diabetic individuals, particularly regarding memory function and learning [2,3,4]. Structural cerebral changes, such as a reduced grey matter volume, have also been described in type 1 diabetes [5,6,7]. Moreover, it is known that type 1 diabetes affects cerebral metabolism and metabolic pathways [8], especially in response to acute hypoglycaemia [9]. Known risk factors for these structural and functional effects on the brain include diabetes onset in early childhood [10, 11] and poor glycaemic control [12]. Recently, the presence of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (IAH), which results from exposure to recurrent hypoglycaemia, has also been associated with reduced cognitive function [13] and structural cerebral decline [5]. The neurochemical mechanism(s) that may precede, underlie or accompany these effects on the brain are not well studied, hence elucidation of such mechanism may provide further insight into detrimental effects of type 1 diabetes on the brain.

1H MR spectroscopy (MRS) is a suitable tool for the non-invasive examination of a range of neuro-metabolites in humans [14]. Previous studies using 1H MRS have suggested that a change in brain glutamate may have a role in neuronal function loss in type 1 diabetes. Under hyperglycaemic conditions, the levels of glutamate and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) were lower in individuals with long-term type 1 diabetes compared with non-diabetic control participants [15]. Since NAA and glutamate are metabolites that mainly reside in neurons, these lower levels were attributed to a loss of neuronal function. However, such lower levels were not found when individuals were studied under euglycaemic conditions [16]. Moreover, in a large cohort, an increase in prefrontal glutamate levels in type 1 diabetes was described, with a linear relation between glutamate levels and lifetime glycaemic control [4]. The impact of recurrent hypoglycaemia on brain metabolite levels is currently not known.

Using IAH as a proxy for significant burden of hypoglycaemia, we aimed to assess the impact of recurrent hypoglycaemia on brain metabolites as measured by 1H MRS by comparing these in individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus and IAH to those with normal awareness of hypoglycaemia (NAH) and non-diabetic control participants. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the effect of potential mediators for structural and functional cerebral decline, such as level of glycaemic control and age at diagnosis, on metabolites in the brain.

Methods

The 1H MRS data were acquired as part of three previously conducted studies [17,18,19], focusing on cerebral lactate levels during euglycaemia and hypoglycaemia, using the hyperinsulinaemic clamp technique. Here we analysed the total neurochemical profile of the participants as seen by 1H MRS, recorded under hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic conditions. These data had not been previously analysed. Details regarding the hyperinsulinaemic glucose clamp have been reported previously [17,18,19]. Participants were not subjected to any intervention other than the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp during data acquisition. All data were acquired between September 2014 and August 2017 and all participants gave written informed consent. The studies were approved by and studied in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board of the Radboud university medical center (Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek Arnhem-Nijmegen) and with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975/1983 and its later amendments and revisions.

The cohort consisted of 13 individuals without diabetes, 18 with type 1 diabetes and NAH, and 13 with type 1 diabetes and IAH. Participants with type 1 diabetes were initially classified as NAH or IAH using the Dutch modified version of the Cox questionnaire [20, 21], and their state of awareness was retrospectively confirmed during clamped hypoglycaemia on the basis of adrenaline and hypoglycaemic symptom responses. HbA1c levels of the individuals with type 1 diabetes were determined at the time of inclusion. Participants with type 1 diabetes were further subdivided into those with optimal glycaemic control (i.e. HbA1c <53 mmol/mol [7.0%]) and suboptimal glycaemic control (i.e., HbA1c ≥53 mmol/mol [7.0%]). Main exclusion criteria were: MRI contraindications, the use of drugs (other than insulin) that may alter glucose metabolism, HbA1c levels >75 mmol/mol (9.0%) and presence of microvascular complications, except for background retinopathy.

MRS protocol and data processing

MRS measurements were performed on a 3T MR system (Tim MAGNETOM Trio (n = 32) or MAGNETOM Prisma-fit (n = 12), Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), using a body coil for excitation and a 12-channel receive-only head coil. A T1-weighted anatomical image (MPRAGE; 256 × 256 mm2 field of view; 1 mm3 isotropic voxels) was used for MRS voxel positioning and for determination of the amount of grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the MRS voxel.

1H MRS data were acquired from a single voxel (22.5–25.0 cm3) in the periventricular region of the brain. A semi-LASER spectroscopy sequence [22] was used with an 8-step phase cycle and an echo time (TE) of 30 ms (Trio) or 33 ms (Prisma-fit), a repetition time (TR) of 3000 ms and 32 averages, combined with WET water suppression (water suppression enhanced through T1 effects) [23]. A water-unsuppressed spectrum was acquired for each participant from the same voxel with a TR of 5000 ms, a TE of 30 or 33 ms and 4 averages, used for eddy-current correction and for absolute metabolite quantification.

Spectra were analysed with LCModel software [24]. The LCModel basis set, one for each TE, was created in Bruker TopSpin (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) and contained 19 metabolites: Ala, Asp, choline, creatine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glucose, Glu, Gln, glutathione, glycerophosphocholine, Gly, lactate, myo-inositol, NAA, N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), phosphocholine, phosphocreatine, scyllo-inositol and taurine. The basis set was extended with a previously measured macromolecular baseline [25]. The spectral region between 0.5 and 4.2 ppm was used in the LCModel analysis. Metabolites quantified with a Cramér–Rao lower bound (CRLB) >50% were classified as undetected and only metabolites quantified with a CRLB <50% in at least half of the spectra were used in the analysis. The CRLB cut-off of 50% was chosen to avoid direct rejection of metabolites with a low concentration [26]. If the covariance between metabolites was consistently high (i.e., r below −0.3), the sum of the related metabolites was reported; this was the case for total NAA (NAA + NAAG), total choline (phosphocholine + glycerophosphocholine) and total creatine (creatine + phosphocreatine), but not for Glu + Gln (mean r: 0.02 ± 0.14). The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spectral linewidths were analysed in the context of quality assessment. SNR was defined as the ratio of the maximum height of the largest signal (i.e., NAA) to twice the root-mean-square of the noise and the spectral linewidth as the full width at half-maximum of the respective water-unsuppressed spectrum. The SNR and linewidths were reported by LCModel.

To determine the relative proportions of grey matter, white matter and CSF in the MRS voxel, we segmented the T1-weighted images using Matlab 2017b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and the VBM8 toolbox in SPM8 (Functional Imaging Laboratory, University College London, London, UK). These fractions were used to estimate the water content in the MRS voxel, assuming a water concentration of 43.3 mol/l in grey matter, 35.9 mol/l in white matter and 55.6 mol/l in CSF [27], and to correct for partial volume effects [28]. Concentrations were also corrected for T1 and T2 relaxation.

Statistical analysis

Differences in metabolite levels between individuals with IAH, those with NAH and non-diabetic control participants were determined using ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests to accommodate the three groups design. Analyses were repeated using ANCOVA to adjust comparisons for voxel content (i.e., the amount of grey matter in the voxel). ANOVA and ANCOVA results were similar; therefore only those calculated using ANOVA are reported.

Linear regression analysis was performed between glutamate levels and HbA1c levels and between glutamate levels and the age at diagnosis of diabetes. In a secondary analysis we subdivided the participants into those with optimal or suboptimal glycaemic control. ANOVAs were conducted to detect differences between non-diabetic individuals, individuals with NAH and optimal glycaemic control (mean HbA1c: 48.2 ± 2.9 mmol/mol [6.5 ± 0.3%], n = 6), those with NAH and suboptimal glycaemic control (59.7 ± 4.8 mmol/mol [7.6 ± 0.4%), n = 12], those with IAH and optimal glycaemic control (47.6 ± 7.7 mmol/mol [6.5 ± 0.7%], n = 5) and those with IAH and suboptimal glycaemic control (58.6 ± 4.9 mmol/mol [7.5 ± 0.4%], n = 8).

Data are presented as mean ± SD. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No correction for multiple comparisons was performed.

Results

The participants were matched for age, sex and BMI, and for diabetes duration and HbA1c levels in the patient groups (Table 1). There were also no significant differences in these variables (except for HbA1c levels) between the subgroups of participants subdivided according to glycaemic control (data not shown). Plasma glucose levels were well in the euglycaemic range during the acquisition of the MRS data, with no differences between groups (overall mean: 5.3 ± 0.6 mmol/l and a mean CV of 10.6%).

The 1H MR spectra were of good quality (see Fig. 1), with comparable linewidths (overall mean: 0.05 ± 0.01 ppm) and SNR (overall mean: 39.7 ± 7.9) between groups. The MRS voxel contained on average ~65–70% (parietal) white matter, with no differences in voxel composition between groups (Table 2).

Example of LCModel analysis of one 1H MR spectrum (top row). The peaks identified include macromolecules (MM), aspartate (Asp), creatine (Cre), glutamine (Gln), glutamate (Glu), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), glutathione (GSH), myo-inositol (mI), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), phosphocholine (PCh), phosphocreatine (PCr), scyllo-inositol (Scyllo) and taurine (Tau). The insert shows the localisation of the MRS voxel

Ten metabolites were consistently quantified using LCModel. Mean CRLBs were <10% for Glu, glutathione, myo-inositol, total creatine, total choline and tNAA and <30% for Asp, Gln, scyllo-inositol and taurine (Table 3).

Brain glutamate levels were significantly higher in individuals with type 1 diabetes, both in those with NAH (+15%, p = 0.013) and in those with IAH (+19%, p = 0.003), when compared with non-diabetic control participants. Glutamate levels did not differ between the two patient subgroups (p = 1.0). Furthermore, we observed higher aspartate levels in type 1 diabetes and IAH (+30%, p = 0.009) compared with non-diabetic control participants. All other metabolite levels, as well as the level of macromolecules, were similar across groups (Fig. 2).

Mean metabolite levels in participants with type 1 diabetes and IAH (T1DM IAH), participants with type 1 diabetes and NAH (T1DM NAH) and non-diabetic control participants. Between group differences were assessed with ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests to accommodate the three groups design; *p < 0.05. Data are mean + SD, with individual data points shown as dots. GSH, glutathione; mI, myo-inositol; MM, macromolecules; Scyllo, scyllo-inositol; Tau, taurine; tCho, total choline; tCre, total creatine; tNAA, total NAA; ww, wet weight

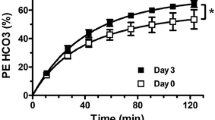

Cerebral glutamate levels were linearly correlated to HbA1c levels in individuals with type 1 diabetes (p = 0.03; r = 0.40; Fig. 3a) and inversely correlated to the age at diagnosis of diabetes (p = 0.04; r = −0.36; Fig. 3b). The variance inflation factor (VIF) between both predictors was 1.19, meaning that there was no noteworthy collinearity within our data. A sensitivity analysis excluding outliers did not materially change these associations. There was no correlation between cerebral glutamate levels and the duration of type 1 diabetes. Subdividing the participants into those with optimal or suboptimal glycaemic control gave further insight into the elevated cerebral glutamate levels. Cerebral glutamate levels were particularly elevated in participants with suboptimal glycaemic control, and particularly in those with IAH (Fig. 4). There were no differences in glutamate levels between both subgroups of individuals with optimal glycaemic control and non-diabetic individuals (Fig. 4). There was no difference between male and female participants.

Correlation between cerebral glutamate levels and HbA1c levels (a) and between cerebral glutamate levels and the age at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (b). Data from participants with type 1 diabetes and IAH (T1DM IAH; white triangles) and participants with type 1 diabetes and NAH (T1DM NAH; black circles), together with the linear fits of the data and the 95% CI, obtained from linear regression analysis. (a) p = 0.03; r = 0.40; (b) p = 0.04; r = −0.36; ww, wet weight

Cerebral glutamate levels. Group means are depicted in black circles. Participants with type 1 diabetes are further subdivided into those with optimal glycaemic control (HbA1c <53 mmol/mol [7.0%]) and those with suboptimal glycaemic control (HbA1c ≥53 mmol/mol). ANOVAs were conducted to detect differences among non-diabetic individuals, and diabetic individuals with NAH and optimal glycaemic control, NAH and suboptimal glycaemic control, IAH and optimal glycaemic control, and IAH and suboptimal glycaemic control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs non-diabetic control participants. ND, non-diabetic control; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; ww, wet weight

Discussion

Here we evaluated the neurochemical profile of participants with type 1 diabetes, with and without IAH, under euglycaemic conditions and compared this with non-diabetic control participants. Our main finding was that brain glutamate levels are elevated in both groups of participants with diabetes compared with healthy non-diabetic control participants. Known risk factors for functional and structural cerebral decline in type 1 diabetes, i.e. glycaemic control and an early age of disease onset, are correlated to these elevated glutamate levels. The presence or absence of IAH did not affect glutamate levels.

Glutamate is one of the most important excitatory neurotransmitters and studies have shown that increased glutamate levels are roughly linearly related with increased excitatory activity [29]. Therefore, changes in glutamate levels have been linked to metabolic activity [29, 30]. The greater cerebral glutamate levels in people with type 1 diabetes as compared with those without diabetes could be interpreted as an upregulation of cerebral metabolism in individuals with type 1 diabetes. However, this contrasts with studies that reported no significant difference in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle rate during euglycaemia between individuals with type 1 diabetes and non-diabetic control participants [31]. Alternatively, glutamate itself may act as a metabolic substrate for the TCA cycle, through conversion to α-ketoglutarate. Previous studies have shown that cerebral glutamate levels drop in response to acute hypoglycaemia in individuals with type 1 diabetes with intact hormonal responses to hypoglycaemia, which was attributed to glutamate acting as an alternative fuel [18, 19, 32]. Glutamate oxidation can complement glucose use [33]. The higher glutamate levels could be the result of a cerebral protection mechanism in response to multiple hypoglycaemic insults, and thus cerebral glucose deprivation, during a lifetime with diabetes. Finally, elevated extracellular glutamate levels are known to be excitotoxic, which triggers various processes that result in neuronal cell death. Glutamate excitotoxicty is thought to be involved in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease [34], which also show higher cerebral glutamate levels [35]. However, since the extracellular level of glutamate in the brain is only a few μmol/l, it is not expected to be detected by 1H MRS.

Our results are in line with a large cohort study in which elevated prefrontal glutamate levels were found in individuals with long-standing type 1 diabetes [4]. These higher glutamate concentrations were associated with lower cognitive function as well as with mild depression, and correlated with lifetime glycaemic control. Here we show that another risk factor for cerebral decline, namely the age of onset of diabetes, also correlated with cerebral glutamate levels. These findings indicate that elevated brain glutamate may be an early marker of the potentially devastating effect of chronic hyperglycaemia, in particular on the developing brain. The presence of IAH alone has only limited additional consequences regarding cerebral glutamate levels. Interestingly, glutamate levels were the highest, although this difference was not significant, in individuals with both IAH and suboptimal HbA1C levels, which may suggest that individuals with the most fluctuating glucose levels are more prone to these alterations.

Our data contrasts with a 1H MRS study that showed a decline in cerebral glutamate levels in people with type 1 diabetes [15]. In that study, however, data were acquired during a hyperglycaemic clamp, which may have altered cerebral metabolism [36, 37]. Furthermore, these lower glutamate levels were only found in a grey-matter-rich voxel and not in a white-matter-rich region as studied here, suggestive of region-specific metabolic alterations, as also described in a rat model of type 1 diabetes [38].

We also found increased aspartate levels in participants with IAH compared with non-diabetic control participants. Aspartate, like glutamate, is an excitatory neurotransmitter and both are synthesised from glucose in the brain. Aspartate and glutamate are also linked through the malate-aspartate shuttle (MAS). However, an increased flux through the MAS implies opposite changes in glutamate and aspartate levels [30], which is not in line with our results.

Our finding of increased glutamate levels in the brain of individuals with type 1 diabetes is also important in the context of studies on brain metabolism with 13C MRS and metabolic modelling. Brain glutamate levels are typically used as an input in such models and often it is assumed that glutamate levels are constant (e.g. no change upon hypoglycaemia) and not different between different groups of individuals (e.g. no difference between individuals with and without diabetes) [31, 39]. These assumptions are critical and deviations may have a significant impact on outcomes. The results of the current study presents an argument for using measured glutamate levels as input in such models.

The present study has some limitations. MRS data were acquired from a large single voxel, which precludes any analysis of the regional dependency of the described alterations. Furthermore, we performed an explorative analysis on multiple metabolites in a rather limited sample size. As a consequence of clamp conditions, insulin levels were elevated albeit within the physiological range. We are, however, unaware of modulating effects of insulin on brain glutamate levels. Furthermore, we used the presence of IAH as proxy for recurrent hypoglycaemia, since habituation to frequent hypoglycaemia underlies the pathogenesis of IAH. We acknowledge that IAH is not an on/off phenomenon, so an impact of hypoglycaemia, which also occurs in individuals with NAH, cannot be fully excluded. Also, we did not actually measure burden of hypoglycaemia, but based on the pathogenesis of IAH we assumed this burden to be greater in people with IAH than in those with NAH. Finally, inherent to the inclusion criteria, the participants with type 1 diabetes all had HbA1c levels below 9.0% and were relatively young. Future research should focus on the effect of more poorly controlled and long-standing diabetes.

In conclusion, we show that there are alterations in neuro-metabolites in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Cerebral glutamate levels are higher in type 1 diabetes and correlate with known risk factors for cerebral decline, suggesting a potential role for glutamate as an early indicator of cerebral complications of type 1 diabetes. The presence of IAH, which usually results from recurrent hypoglycaemia, has only limited additional impact on the neurochemical profile of individuals with type 1 diabetes.

Data availability

Data may be obtained from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- CRLB:

-

Cramér–Rao lower bound

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- IAH:

-

Impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia

- MAS:

-

Malate-aspartate shuttle

- MRS:

-

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NAA:

-

N-acetylaspartate

- NAAG:

-

N-acetylaspartylglutamate

- NAH:

-

Normal awareness of hypoglycaemia

- SNR:

-

Signal-to-noise ratio

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

- TE:

-

Echo time

- TR:

-

Repetition time

References

Moheet A, Mangia S, Seaquist ER (2015) Impact of diabetes on cognitive function and brain structure. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1353(1):60–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12807

Cukierman-Yaffe T (2014) Diabetes, dysglycemia and cognitive dysfunction. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 30(5):341–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.2507

Kodl CT, Seaquist ER (2008) Cognitive dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev 29(4):494–511. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2007-0034

Lyoo IK, Yoon SJ, Musen G et al (2009) Altered prefrontal glutamate-glutamine-gamma-aminobutyric acid levels and relation to low cognitive performance and depressive symptoms in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66(8):878–887. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.86

Bednarik P, Moheet AA, Grohn H et al (2017) Type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia are associated with reduced brain gray matter volumes. Front Neurosci 11:529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00529

Hughes TM, Ryan CM, Aizenstein HJ et al (2013) Frontal gray matter atrophy in middle aged adults with type 1 diabetes is independent of cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes complications. J Diabetes Complicat 27(6):558–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.07.001

Musen G, Lyoo IK, Sparks CR et al (2006) Effects of type 1 diabetes on gray matter density as measured by voxel-based morphometry. Diabetes 55(2):326–333. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0520

Duarte JM (2016) Metabolism in the diabetic brain: neurochemical profiling by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Diabetes Metab Disord 3:011

Rooijackers HM, Wiegers EC, Tack CJ, van der Graaf M, de Galan BE (2016) Brain glucose metabolism during hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes: insights from functional and metabolic neuroimaging studies. Cell Mol Life Sci 73(4):705–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2079-8

Mazaika PK, Weinzimer SA, Mauras N et al (2016) Variations in brain volume and growth in young children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 65(2):476–485. https://doi.org/10.2337/db15-1242

Ryan C, Vega A, Drash A (1985) Cognitive deficits in adolescents who developed diabetes early in life. Pediatrics 75:921–927

Jacobson AM, Ryan CM, Cleary PA et al (2011) Biomedical risk factors for decreased cognitive functioning in type 1 diabetes: an 18 year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) cohort. Diabetologia 54(2):245–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1883-9

Hansen TI, Olsen SE, Haferstrom ECD et al (2017) Cognitive deficits associated with impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 60(6):971–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4233-3

Oz G, Alger JR, Barker PB et al (2014) Clinical proton MR spectroscopy in central nervous system disorders. Radiology 270(3):658–679. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13130531

Mangia S, Kumar AF, Moheet AA et al (2013) Neurochemical profile of patients with type 1 diabetes measured by (1)H-MRS at 4 T. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(5):754–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.13

Bischof MG, Brehm A, Bernroider E et al (2006) Cerebral glutamate metabolism during hypoglycaemia in healthy and type 1 diabetic humans. Eur J Clin Investig 36(3):164–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01615.x

Wiegers EC, Rooijackers HM, Tack CJ et al (2017) Effect of exercise-induced lactate elevation on brain lactate levels during hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes 66(12):3105–3110. https://doi.org/10.2337/db17-0794

Wiegers EC, Rooijackers HM, Tack CJ, Heerschap A, de Galan BE, van der Graaf M (2016) Brain lactate concentration falls in response to hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes 65(6):1601–1605. https://doi.org/10.2337/db16-0068

Wiegers EC, Rooijackers HM, Tack CJ, et al (2018) Effect of lactate administration on brain lactate levels during hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab: 271678X18775884

Janssen MM, Snoek FJ, Heine RJ (2000) Assessing impaired hypoglycemia awareness in type 1 diabetes: agreement of self-report but not of field study data with the autonomic symptom threshold during experimental hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 23(4):529–532. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.4.529

Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, Julian D, Schlundt D, Polonsky W (1995) Reduced awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM. A prospective study of hypoglycemic frequency and associated symptoms. Diabetes Care 18(4):517–522. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.18.4.517

Scheenen TW, Klomp DW, Wijnen JP, Heerschap A (2008) Short echo time 1H-MRSI of the human brain at 3T with minimal chemical shift displacement errors using adiabatic refocusing pulses. Magn Reson Med 59(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21302

Ogg RJ, Kingsley PB, Taylor JS (1994) WET, a T1- and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in vivo localized 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson B 104(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048

Provencher SW (1993) Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med 30(6):672–679. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910300604

Wijnen JP, van Asten JJ, Klomp DW et al (2010) Short echo time 1H MRSI of the human brain at 3T with adiabatic slice-selective refocusing pulses: reproducibility and variance in a dual center setting. J Magn Reson Imaging 31(1):61–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.21999

Kreis R (2016) The trouble with quality filtering based on relative Cramer-Rao lower bounds. Magn Reson Med 75(1):15–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25568

Provencher SW (2018) LCModel & LCMgui user’s manual. Available from http://s-provencher.com/pub/LCModel/manual/manual.pdf

Quadrelli S, Mountford C, Ramadan S (2016) Hitchhiker’s guide to voxel segmentation for partial volume correction of in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Insights 9:1–8

Rae CD (2014) A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem Res 39(1):1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-013-1199-5

Mangia S, Giove F, Dinuzzo M (2012) Metabolic pathways and activity-dependent modulation of glutamate concentration in the human brain. Neurochem Res 37(11):2554–2561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-012-0848-4

van de Ven KC, Tack CJ, Heerschap A, van der Graaf M, de Galan BE (2013) Patients with type 1 diabetes exhibit altered cerebral metabolism during hypoglycemia. J Clin Invest 123:623–629

Terpstra M, Moheet A, Kumar A, Eberly LE, Seaquist E, Oz G (2014) Changes in human brain glutamate concentration during hypoglycemia: insights into cerebral adaptations in hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in type 1 diabetes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34(5):876–882. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2014.32

Dienel GA (2013) Astrocytic energetics during excitatory neurotransmission: what are contributions of glutamate oxidation and glycolysis? Neurochem Int 63(4):244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.015

Lewerenz J, Maher P (2015) Chronic glutamate toxicity in neurodegenerative diseases-what is the evidence? Front Neurosci 9:469

Duarte JM, Schuck PF, Wenk GL, Ferreira GC (2014) Metabolic disturbances in diseases with neurological involvement. Aging Dis 5:238–255

Glaser N, Ngo C, Anderson S, Yuen N, Trifu A, O’Donnell M (2012) Effects of hyperglycemia and effects of ketosis on cerebral perfusion, cerebral water distribution, and cerebral metabolism. Diabetes 61(7):1831–1837. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1286

Heikkila O, Lundbom N, Timonen M, Groop PH, Heikkinen S, Makimattila S (2009) Hyperglycaemia is associated with changes in the regional concentrations of glucose and myo-inositol within the brain. Diabetologia 52(3):534–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1242-2

Zhang H, Huang M, Gao L, Lei H (2015) Region-specific cerebral metabolic alterations in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats: an in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35(11):1738–1745. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2015.111

De Feyter HM, Mason GF, Shulman GI, Rothman DL, Petersen KF (2013) Increased brain lactate concentrations without increased lactate oxidation during hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetic individuals. Diabetes 62(9):3075–3080. https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-0313

Acknowledgements

Some of the data from this study were presented as an abstract at the Annual Dutch Diabetes Research Meeting, Oosterbeek, the Netherlands in 2018. We thank all the volunteers for their participation in this work. We are indebted to K. Saini, S. Hins-de Bree and A. Hofboer-Kapteijns (research nurses, Radboud university medical center) for assistance during the glucose clamps.

Contribution statement

EW, HR, BdG and MvdG designed the study with input from JvA, CT and AH. HR recruited the participants and performed the glucose clamps. EW and MvdG developed and implemented the MRS methods and the MRS sequence. EW and HR collected the data. JvA implemented the LCModel analysis. EW analysed the MRS data. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. BdG is the guarantor of this work.

Funding

Research support from the Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation (DFN 2012.00.1542) and the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiegers, E.C., Rooijackers, H.M., van Asten, J.J. et al. Elevated brain glutamate levels in type 1 diabetes: correlations with glycaemic control and age of disease onset but not with hypoglycaemia awareness status. Diabetologia 62, 1065–1073 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4862-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4862-9