Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is more frequent in patients with diabetes than in the general population. However, characteristics contributing to AF risk in diabetes remain speculative.

Methods

Observational study of 83,162 patients with type 2 diabetes, aged 30-79 years, with no baseline AF, 17% had history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 3.3% history of congestive heart failure (CHF), followed up for development of AF during mean 6.8 years from 2005–2007 to 2012. A subgroup of 67,780 patients without history of CVD or CHF was also analysed.

Results

Using Cox regression, cardiovascular risk factors associated with risk for AF were updated mean BMI (HR 1.31 per 5 kg/m2) or obesity (HR 1.51), updated mean systolic BP (SBP; HR 1.13 per 10 mmHg) or hypertension (HR 1.71), and cumulative microalbuminuria (HR 1.21), p < 0.001 for all analyses. Male sex, increasing age and height were also significant predictors. HRs were 1.76 for a history of CHF and 2.56 for in-study CHF, while 1.32 for history of CVD and 1.38 for in-study CHD (p < 0.001). Among patients without history of CVD or CHF, significant predictors were similarly BMI, SBP, and cumulative microalbuminuria and CHF. The risk of AF differed in the subgroups achieving or not achieving a target BP < 140/85 mmHg. The HRs for AF were (per 10 mmHg increase) 0.88 and 1.24, respectively.

Conclusions/interpretation

The modifiable risk factors high BP, high BMI and albuminuria were strongly associated with AF in type 2 diabetes. CVD, advancing age and height were also associated with AF in type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias in the general population [1]. It is a strong risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality, and it is associated with congestive heart failure (CHF) [2, 3]. Risk factors for development of AF in the general population have been shown to be intrinsic cardiac causes like CHF and valve disease, and also cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension, obesity and smoking [4–9]. A meta-analysis found a smaller increased risk of 1.24 (1.06–1.40) for AF with diabetes than with no diabetes in studies adjusting for multiple risk factors [10]. However, a recent women’s health study found that the increased risk associated with type 2 diabetes was mainly mediated by changes in other AF risk factors [11].

Further, AF has been shown to have a strong impact on risk for cardiovascular complications and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes [12, 13], who generally have risks of cardiovascular complications at least twice as high as in those without diabetes [14, 15]. With this background, it is a particularly important task to estimate risk factors for AF in patients with diabetes. To our knowledge, such studies have not been presented previously.

The aim of this study was to assess various risk factors associated with the development of AF in an observational cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetes obtained from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR).

Methods

The Swedish NDR

The NDR was initiated in 1996 as a tool for quality assurance and improvement in diabetes care with local feedback. Annual reporting to the NDR is carried out by trained physicians and nurses via the internet or via clinical records databases, with information collected during patient visits at hospital outpatient clinics and primary healthcare centres nationwide. All included patients have agreed by informed consent to register before inclusion. The Regional Ethics Review Board at the University of Gothenburg approved this study. Several reports concerning trends in risk factor control and risk prediction in the NDR have been published previously [13, 16–21].

Patients

In this study, we assessed several risk factors for the development of AF in an observational study of patients with type 2 diabetes. Patients were treated in daily practice at primary healthcare clinics and hospitals. We used AF diagnoses in Swedish national in-patient and mortality registers, kept by the National Board of Health and Welfare, as these registers have been shown to have good validity for AF classification indicating feasibility for use in prospective studies, compared with examination by electrocardiograms [7]. Linkage of registers was performed using the unique person identity number (PIN).

We included 83,162 female and male patients with type 2 diabetes registered in the NDR, with data available for all analysed variables, without AF at study baseline. They were followed prospectively from baseline years 2005–2007 to final year 2012 for the development of AF. The inclusion criteria were age range 30–79 years, baseline BMI ≥18 kg/m2, HbA1c ≥5.0% (38 mmol/mol), plasma creatinine <150 μmol/l and no history of bariatric surgery. A subgroup of 67,780 patients without AF, no history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and no history of CHF at baseline was also analysed.

The definition of type 2 diabetes was treatment with diet only, oral hypoglycaemic agents only, or onset age of diabetes ≥40 years and insulin only or combined with oral agents. Only 0.4% of the patients had an onset age <30 years, and 2% had onset age <40 years.

Examinations at baseline

Clinical characteristics at baseline in 2005–2007 were type of hypoglycaemic treatment, age, diabetes duration, sex, systolic BP (SBP), HbA1c, weight, height, smoking, total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerols, cumulative microalbuminuria, plasma creatinine, use of antihypertensive drugs and lipid-lowering drugs, and a history of CVD or a history of CHF defined using registry data as described below. We stratified educational levels into lower (≤9 years), intermediate (10–12 years [upper secondary school]) and higher (college/university). BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight/height2, and obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. A smoker was defined as a patient smoking one or more cigarettes per day, or smoking tobacco using a pipe, or who had stopped smoking within the past 3 months. The Swedish standard for BP recording, used in the NDR, is the mean value (mmHg) of two supine readings (Korotkoff 1–5) with a cuff of appropriate size, after at least 5 min of rest. Hypertension was defined as treated with antihypertensive drugs or untreated with BP ≥140/90 mmHg. HbA1c analyses were quality assured nationwide by regular calibration with the HPLC Mono-S method, and HbA1c values were converted to the DCCT standard for use in this study using the formula: HbA1c (%, DCCT) = 0.923 × HbA1c (Mono-S) + 1.345; R 2 = 0.998 [22], and also to International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) standard (mmol/mol). Albuminuria was defined as cumulative, urine albumin excretion >20 μg/min in two out of three consecutive tests (microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria).

Registry data exposure at baseline and in-study

All events were retrieved by data linkage with the Swedish Cause of Death and Hospital Discharge Registers, which is a reliable validated alternative to revised hospital discharge and death certificates [23, 24]. AF diagnosed before or at baseline was defined as ICD-10 (www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/) code I48. A history of CVD before baseline was defined as nonfatal CHD or nonfatal stroke, whichever came first. Nonfatal CHD was defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction (ICD-10 code I21), unstable angina (ICD-10 code I20.0), percutaneous coronary intervention and/or coronary artery bypass grafting. Stroke was defined as cerebral infarction, intracerebral haemorrhage or unspecified stroke (ICD-10 codes I61, I63, I64, I67.9). Furthermore, in-study CHF during follow-up was defined as I50, and in-study myocardial infarction during follow-up was defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction (ICD-10 code I21).

Definition of outcome at follow-up

The endpoint used in this study was AF defined as ICD-10 code I48. All patients were followed from the baseline examination until diagnosis of AF, death, or otherwise until censor date 31 December 2012. Mean follow-up was 6.8 years.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics in all patients, and in those with or without AF as outcome during follow-up, are presented as means ± 1 SD or frequencies in Table 1, with significance levels for differences estimated with Student’s t test for means and χ 2 test for frequencies. Incidence of AF as outcome in all patients, by various age subgroups, and subgroups of diabetes duration, expressed as cases, % cases, or as cases per 1000 person-years are given in electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1.

Predictors of AF as outcome during the study period were estimated using Cox regression with HRs, 95% CI, Wald χ2 values as measure of strength of significance, and p values for significance; see Table 2 for all patients and Tables 3 and 4 for various subgroups. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed for all covariates with the test of all time-dependent covariates simultaneously introduced. Interactions between the risk factor predictors were analysed with maximum likelihood estimation and found to be non-significant (p > 0.05). All variables in Table 1 were introduced as covariates in the Cox regressions: the age variable was introduced per ten years, SBP per 10 mmHg, BMI per 5 kg/m2, and height per decimetre. Use of stepwise Cox regression allowing only significant predictors to remain in the model did not alter HRs obtained.

We also analysed updated mean values for BMI and SBP, introduced instead of the baseline values in analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3 as strictly time-dependent variables at the Cox regressions, with each of these variables measured over time as an updated mean of annual measurements, calculated for each individual from baseline to each year of follow-up, with the last observation carried forward for missing data. In case of an event during follow-up, the period for estimating updated mean BMI or SBP was from baseline to the year before this event occurred. Otherwise this period was from baseline to the censor year. Similarly, updated values for in-study CHF and CHD during the study period were introduced as strictly time-dependent variables in these Cox regressions.

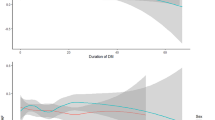

A Cox model was also used to estimate 7 year incidence (1–survival rate) for AF (Fig. 1), where model output was the adjusted 7 year incidence in each participant, adjusted for covariates as given in Table 2. Both age and the square of age, or correspondingly SBP and the square of SBP, or BMI and the square of BMI, were included in the Cox model to analyse nonlinear relationships. The output was further transformed by SAS Proc Transreg (http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_transreg_sect006.htm) to produce graphical spline outputs, with nine knots at the predictor deciles, allowing for the spline to bend at all knots for maximal adoption to data.

(a–f) Penalised B-splines for 7 year incidence (95% CI) of AF across the distributions of age, updated mean SBP or updated mean BMI, in 67,780 patients with type 2 diabetes and no history of CVD or heart failure. Subgroups: (a) age 30–65 years; (b) age 65–79 years; (c) SBP < 140 mmHg; (d) SBP ≥ 140 mmHg; (e) BMI < 30 kg/m2; (f) BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2

The population attributable risk (PAR) was estimated as Pe (HRe −1)/[1 + Pe (HRe −1)], where Pe is the prevalence of the exposure (e.g. proportion of obesity) and HRe is the HR of disease due to that exposure. PAR indicates the proportion of cases that would be avoided in a population if the factor were eliminated, and depends on the prevalence of the risk factor and the magnitude of its association with the disease (HR) [25].

Results

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of all 83,162 patients, with mean age 64.1 years, 58% male sex and mean diabetes duration 7.9 years. Obesity was found in 43%, while 16% of all patients were smokers. Antihypertensive agents were given to 72% and hypertension was found in 82%. Lipid-lowering agents were given to 56% of participants. A history of CVD was present in 17%, and a history of CHF in 3.3%. Separating all patients into those with or without AF during follow-up showed that those with AF had significantly higher mean age (68 years), diabetes duration, BMI, blood lipids and BP, as well as more males, obesity, albuminuria, hypertension and history of CVD and CHF. The subgroup of 67,780 patients with no history of CHF or CVD showed similar means and frequencies.

The incidence rates (%) and the incidence rates per 1000 person-years for AF were 5.0% and 9.2 in all patients, with 5.4% and 9.9 in males, 4.5% and 8.2 in females (ESM Table 1). Corresponding data in subgroups by quartiles of age or quartiles of diabetes duration are also presented in ESM Table 1. In all patients, incidence increased considerably from 1.9% in people aged 30–58 years, to 4.0% in people aged 59–64 years, to 6.1% in people aged 65–71 years and to 8.0% in people aged 72–79 years (p for trend < 0.001). Corresponding incidences by increasing quartiles of duration were 4.2%, 4.6%, 5.0% and 6.1% (p < 0.001).

Table 2 shows adjusted HRs with baseline predictor values for the development of AF using Cox regression in all 83,162 patients, followed up for mean 6.8 years with 451,507 person-years. Independent predictors were age (HR 2.00 per 10 years), BMI (HR 1.30 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI), SBP (HR 1.04 per 10 mmHg increase), cumulative albuminuria (HR 1.25), male sex (HR 1.39), history of CHF (HR 1.61) and history of CVD (HR 1.32), all p < 0.001.

A complementary analysis using baseline body weight and height instead of BMI as predictors yielded HR 1.22 per 10 kg increase in body weight and 1.15 per dm increase in height, both p < 0.001 (ESM Table 2). Furthermore, complementary use of obesity instead of baseline BMI and hypertension instead of baseline SBP yielded HR 1.51 for obesity and 1.71 for hypertension, both p < 0.001 (ESM Table 2).

Somewhat increased HRs compared with using baseline values in all patients were seen when using updated mean values of BMI and SBP, with HR increasing to 1.31 for updated mean BMI and to 1.13 for updated mean SBP (see Table 2). Furthermore, HR for in-study CHF and in-study CHD were 2.56 and 1.38, all p < 0.001.

Subgroup with no previous CHF/CVD

Table 3 presents the subgroup of 67,780 patients without history of CVD or CHF at baseline. Similar HRs were also seen with the highest HR for updated mean BMI (HR 1.33 per 5 units), updated mean SBP (HR 1.14 per 10 mmHg), albuminuria (HR 1.22) and in-study CHF (HR 2.69), all p <0.001.

Subgroups by various predictors

The incidence of AF during 7 years of follow-up was 5.6% in patients with hypertension and 2.1% with normotension; 5.6% with BP ≥140/85 mmHg and 4.3% with BP <140/85 mmHg; 5.9% with obesity and 4.3% with normal or overweight; 6.5% with albuminuria and 4.5% with no albuminuria (all p < 0.001), while 5.0% with both HbA1c <7% (54 mmol/mol) and ≥7%.

Table 4 shows, among all patients, that subdivision by age below or above 65 years yielded somewhat higher HR among the younger patients for BMI, SBP, history of CHF or CVD, and in-study CHF or CHD, and the effects of most predictors were inconsistent across the age subgroups due to significant interactions. Concerning the BP treatment target of 140/85 mmHg, those below or above this target had similar HR for most risk factors, and only BMI was inconsistent across the BP subgroups due to a clearly significant interaction. However, the SBP-mediated risk per 10 mmHg for AF over the whole BP range differed in the subgroup achieving the target <140/85 mmHg, HR 0.88 with a J-shaped risk curve, in comparison with those with BP ≥140/85 mmHg, where the HR was 1.24 per 10 mmHg.

Those with HbA1c below or above the treatment target level of 7% had almost similar HR for most risk factors, although the effects for previous and in-study CHF and in-study CHD were somewhat higher with HbA1c <7% (54 mmol/mol), and the effects of the predictors were consistent across the HbA1c subgroups due to non-significant interactions.

Correspondingly, in the subgroup with no history of CHF or CVD, Fig. 1 shows B-splines in a Cox model for 7 year AF incidence across the distributions of age, SBP or BMI. It is seen that a J-curve exists for SBP below 110 mmHg, although otherwise increasing AF incidence with higher age, BMI or SBP.

PAR

PAR with 95% CI was 37 (30, 43)% for hypertension, 18 (15, 20)% for obesity, 6 (4, 8)% for albuminuria, 5 (3, 6)% for previous CVD and 3 (1, 4)% for previous CHF, expressing the proportion of cases that would be avoided in a population if the risk factor were eliminated.

Discussion

This large observational study of patients with type 2 diabetes aged 30–79 years showed a high incidence for development of AF when followed for 7 years. We found high HRs for AF using Cox regression with structural cardiac disease (previous or in-study CHF, previous CVD, in-study CHD), with increasing cardiovascular risk factors (BP/hypertension, BMI/obesity and cumulative microalbuminuria), and also with increasing height, after adjustment for clinical characteristics, other conventional risk factors and treatment. Furthermore, a J-curve was observed for SBP below 110 mmHg. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of risk factors for AF in type 2 diabetes patients, and should be of particular interest as AF is a strong risk factor for stroke, CHF and cardiovascular mortality [2, 3], and as such complications generally are around twice as common in middle-aged and elderly patients with diabetes than in those with no diabetes [14, 15].

Others have found incidences of AF among middle-aged and elderly people in the general population of 5–10% when followed for 10 years [5, 7], while we found around 4–6% in patients with type 2 diabetes followed for 7 years. Estimating incidences per 1000 person-years, the rate was 2–8 per 1000 person-years at ages 50 to 75 years in the general population [4, 7–9, 26], while around 7–15 per 1000 person-years in the corresponding age interval of our study. In older people, however, the Framingham study found incidence of 15–17 per 1000 person-years in individuals aged 75–79 years [4], similar to our study. To summarise, incidence rates of AF in middle-aged up to 75 years tended to be around two times higher among our type 2 diabetes patients than in the general population, which is a higher risk estimate than the risk increase of 25–40% with diabetes compared with patients without diabetes presented in a recent meta-analysis [10].

Concerning studies analysing risk factors for AF in the general population, the Framingham study using time-updated logistic regression [4], or Cox regression [5], found highly significant risks for AF with advancing age, hypertension, obesity, smoking, previous CHF, myocardial infarction and valve disease. The Malmö study [7] found highly significant risks for AF with obesity (HR 1.88), hypertension (HR 1.78), current smoking (HR 1.2), history of CHF (HR 4.5) and history of myocardial infarction (HR 2.0) at Cox regression. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study [9] found the highest risks for AF with hypertension, obesity, smoking and previous cardiac disease.

It has been speculated as to whether longer diabetes duration and higher HbA1c levels may be associated with risk for AF [27]. Although we could not verify such an association, it should be pointed out that others have verified an association between high HbA1c values and increased risk for CHF [28], where CHF per se is a risk factor for AF.

Cumulative microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria as risk factors for AF in diabetes have not been described previously in the literature. As HbA1c is associated with development of albuminuria as a marker for diabetic microangiopathy, and also as albuminuria has a strong association with the risk of CVD in type 2 diabetes, this underscores the importance of glycaemic-lowering treatment with the aim to avoid the development of albuminuria.

Our finding of high HR for AF of 1.71 with hypertension is affected by the high prevalence of hypertension at study baseline. However, as hypertension is frequent in type 2 diabetes, with a prevalence of 87% in a cross-sectional NDR survey of 180,369 patients in 2009 (although lower in subgroups with ages 30–39, 40–49 and 50–59 years: 40%, 60% and 77%, respectively [29]), this implies that treatment of hypertension should be an important task in order to reduce the incidence of AF. This study showed increasing AF risk with higher SBP, but also a J-curve shaped association at the lowest SBP values. This J-curve was clearly demonstrated for SBP 110 mmHg or below in the subgroup with no history of CHF or CVD (see Fig. 1c), implying that this effect was not due to reverse causation by previous CHF or CVD.

Obesity was strongly associated with risk for AF in this study of patients with type 2 diabetes, and also in other studies of the general population. As obesity can be regarded as a marker for insulin resistance, it has been speculated that insulin resistance is a background risk factor for AF as an underlying pathophysiological mechanism [6]. The Gothenburg study has reported that obesity as a risk factor for AF is affected by large body size in youth and weight gain during early life as specific characteristics of obesity. Cross-sectional findings among patients with type 2 diabetes in the NDR have shown a high proportion of obesity—39% of males and 46% of females [30]. A large 5 year study in the general population found that adjusted HR for AF was 1.08 per kg/m2 increase in BMI [31]. If obesity can be regarded as a causative factor for AF, this implies that further studies on the effect of intensified measures for improved lifestyle on risk for AF should be of value in type 2 diabetes. A recent smaller study showed that weight reduction combined with close management of hypertension and other risk factors results in fewer AF events and less symptom burden in patients with symptomatic AF and BMI >27 kg/m2 compared with no weight reduction, i.e. risk factor management alone [32]. One study found that the increased risk for AF with obesity was highest in patients with an enlarged left atrium [33], and a Framingham study implied that the increased risk of AF associated with obesity appears to be mediated by left atrial dilatation [34].

The main strengths of the present study are the large number of participants, including patients from a nationwide diabetes register with high coverage containing data from daily clinical practice representing real-life situations, and with no exclusion criteria regarding risk factors. Follow-up of outcomes was assured for all patients with the use of data linkage to outcome registers, which is a proven reliable and validated method. Furthermore, both baseline data and data obtained yearly during follow-up were taken into account. The limitations of this study were that we had no data on valvular heart disease, echocardiographic cardiac features, specific types of antihypertensive drug treatments or specific diets used. Although unknown covariates cannot be excluded, extensive adjustments were performed for clinical characteristics, conventional risk factors, drug treatment and previous diseases.

Conclusion

In conclusion, observed incidence rates of AF tended to be high, especially in middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Prevention of AF is of paramount importance with early detection of risk factors for AF if possible, especially as incidence increases with an ageing population. AF has life-threatening sequelae with development of thromboembolic events and heart failure [35, 36]. This study showed that strong independent risk factors for AF in type 2 diabetes were high SBP/hypertension, high BMI/obesity and albuminuria as a marker for microangiopathic cardiac disease. Furthermore, CHF, advancing age and height were also associated with higher AF risk.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- NDR:

-

National Diabetes Register

- PAR:

-

Population attributable risk

- SBP:

-

Systolic BP

References

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA et al (2001) Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 285:2370–2375

Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM (1982) Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 306:1018–1022

Friberg J, Scharling H, Gadsbøll N, Truelsen T, Jensen GB, Copenhagen City Heart Study (2004) Comparison of the impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of stroke and cardiovascular death in women versus men (The Copenhagen City Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 94:889–894

Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA (1994) Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 271:840–844

Schnabel RB, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr et al (2009) Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet 373:739–745

Östgren CJ, Merlo J, Råstam L, Lindblad U (2004) For Skaraborg Hypertension and Diabetes Project. Atrial fibrillation and its association with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in a Swedish community. Diab Obes Metab 6:367–374

Smith JG, Platonov PG, Hedblad B, Engström G, Melander O (2010) Atrial fibrillation in the Malmö diet and cancer study: a study of occurrence, risk factors and diagnostic validity. Eur J Epidemiol 25:95–102

Rosengren A, Hauptman PJ, Lappas G, Olsson L, Wilhelmsen L, Swedberg K (2009) Big men and atrial fibrillation: effects of body size and weight gain on risk of atrial fibrillation in men. Eur Heart J 30:1113–1120

Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Folsom AR et al (2011) Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation 123:1501–1508

Huxley RR, Filion KB, Konety S, Alonso A (2011) Meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 108:56–62

Schoen T, Pradhan AD, Albert CM, Conen D (2012) Type 2 diabetes and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1421–1428

Du X, Ninomiya T, de Galan B, on behalf of the ADVANCE Collaborative Group et al (2009) Risks of cardiovascular events and effects of routine blood pressure lowering among patients with type 2 diabetes and atrial fibrillation: results of the ADVANCE study. Eur Heart J 30:1128–1135

Zethelius B, Eliasson B, Cederholm J et al (2011) A new model for 5-year risk of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes – from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Diab Res Clin Pract 93:276–284

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration (2003) The effects of diabetes on the risks of major cardiovascular diseases and death in the Asia-Pacific region. The Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Diabetes Care 26:360–366

Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M (2006) Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 332:73–78

Nilsson PM, Cederholm J (2011) Diabetes, hypertension, and outcome studies: overview 2010. Diabetes Care 34(Suppl 2):S109–S113

Eeg-Olofsson K, Cederholm J, Nilsson PM et al (2010) New aspects of HbA1c as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: an observational study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). J Intern Med 268:471–482

Cederholm J, Zethelius B, Gudbjörnsdottir S et al (2009) Effect of tight control of HbA1c and blood pressure on cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: an observational study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Diab Res Clin Pract 86:74–81

Gudbjörnsdottir S, Eliasson B, Cederholm J, on behalf of the National Diabetes Register (NDR) et al (2011) Additive effects of glycaemia and dyslipidaemia on risk of cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: an observational study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Diabetologia 54:2544–2551

Cederholm J, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Eliasson B, Zethelius B, Eeg-Olofsson K, Nilsson P (2012) Blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: further findings from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR-BP II). J Hypertens 30:2020–2030

Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Zethelius B, Eeg-Olofsson K (2014) Cederholm J; on behalf of the NDR. LDL-cholesterol versus non-HDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio and risk for coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21:1420–1428

Hoelzel W, Weykamp C, Jeppsson JO et al (2004) IFCC reference system for measurement of hemoglobin A1c in human blood and the national standardization schemes in the United States, Japan, and Sweden: a method-comparison study. Clin Chem 50:166–174

Merlo J, Lindblad U, Pessah-Rasmussen H et al (2000) Comparison of different procedures to identify probable cases of myocardial infarction and stroke in two Swedish prospective cohort studies using local and national routine registers. Eur J Epidemiol 16:235–243

Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A (1994) Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 90:583–612

Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C (1998) Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health 38:15–19

Watanabe H, Tanabe N, Watanabe T et al (2008) Metabolic syndrome and risk of development of atrial fibrillation: the Niigata preventive medicine study. Circulation 117:1255–1260

Dublin S, Glazer NL, Smith NL et al (2010) Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and risk of atrial fibrillation. J Gen Intern Med 25:853–858

Lind M, Olsson M, Rosengren A, Svensson AM, Bounias I, Gudbjörnsdottir S (2012) The relationship between glycaemic control and heart failure in 83,021 patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 55:2946–2953

Nilsson PM, Cederholm J, Zethelius B, Eliasson B, Eeg-Olofsson K, Gudbjörnsdottir S (2011) Trends in blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes – data from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Blood Press 20:348–354

Cederholm J, Eliasson B, Zethelius B, Eeg-Olofsson K, Gudbjörnsdottir S (2013) Risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Results from the Swedish National Diabetes Register compared with international studies. A report from the Swedish National Diabetes Registry (NDR). (Abstract in English [Article in Swedish]). Lakartidningen 17–18:882–885

Frost L, Juul Hune L, Vestergaard P (2005) Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish diet, cancer, and health study. Am J Med 118:489–495

Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP et al (2013) Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310:2050–2060

Conen D, Glynn RJ, Sandhu RK, Tedrow UB, Albert CM (2013) Risk factors for incident atrial fibrillation with and without left atrial enlargement in women. Int J Cardiol 168:1894–1899

Wang TJ, D’Agostino R Sr, Vasan RS et al (2004) Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 292:2471–2477

Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ et al (2007) Coronary ischemic events after first atrial fibrillation: risk and survival. Am J Med 120:357–363

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D et al (2003) Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 107:2920–2925

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the regional NDR coordinators, all participating nurses, physicians and other staff who have contributed to the NDR. Most of all, we would like to thank the patients who support the NDR, both individually and collectively through their patient organisation, the Swedish Diabetes Federation. The results and views of the present study represent the authors and not necessarily any official views of the Swedish Medical Products Agency where one author is employed (BZ).

Funding

The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions funds the NDR.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

BZ and JC researched the data. JC performed the statistical analyses. BZ and JC wrote the manuscript. All authors designed the study, revised and reviewed the article and contributed to the discussion, and gave final approval of the manuscript to be submitted. BZ and JC are guarantors of the present work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 26 kb)

ESM Table 2

(PDF 82 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zethelius, B., Gudbjörnsdottir, S., Eliasson, B. et al. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetes: report from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Diabetologia 58, 2259–2268 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3666-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3666-9