Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

To test among diabetes-free urban community-dwelling adults the hypothesis that the proportion of African genetic ancestry is positively associated with glycaemia, after accounting for other continental ancestry proportions, BMI and socioeconomic status (SES).

Methods

The Boston Area Community Health cohort is a multi-stage 1:1:1 stratified random sample of self-identified African-American, Hispanic and white adults from three Boston inner city areas. We measured 62 ancestry informative markers, fasting glucose (FG), HbA1c, BMI and SES (income, education, occupation and insurance status) and analysed 1,387 eligible individuals (379 African-American, 411 Hispanic, 597 white) without clinical or biochemical evidence of diabetes. We used three-heritage multinomial linear regression models to test the association of FG or HbA1c with genetic ancestry proportion adjusted for: (1) age and sex; (2) age, sex and BMI; and (3) age, sex, BMI and SES.

Results

Mean age- and sex-adjusted FG levels were 5.73 and 5.54 mmol/l among those with 100% African or European ancestry, respectively. Using per cent European ancestry as the referent, each 1% increase in African ancestry proportion was associated with an age- and sex-adjusted FG increase of 0.0019 mmol/l (p = 0.01). In the BMI- and SES-adjusted model the slope was 0.0019 (p = 0.02). Analysis of HbA1c gave similar results.

Conclusions/interpretation

A greater proportion of African genetic ancestry is independently associated with higher FG levels in a non-diabetic community-based cohort, even accounting for other ancestry proportions, obesity and SES. The results suggest that differences between African-Americans and whites in type 2 diabetes risk may include genetically mediated differences in glucose homeostasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

African-Americans and US Hispanics appear to have higher prevalence, earlier onset and more rapidly progressive type 2 diabetes with higher levels of glycaemia (denoted by HbA1c) at diagnosis and with more subsequent complications relative to US whites [1–6]. Race/ethnicity and related social and economic barriers to prevention weaken the translation to healthy lifestyles and effective healthcare necessary to reduce and ameliorate type 2 diabetes [4, 5, 7]. Although social and behavioural factors clearly increase diabetes disease risk [8], diabetes prevention efforts in the US aimed at social and behavioural factors remain incompletely effective, so further work incorporating racial/ethnic diabetes disparities upstream of diabetes development is needed to address the root causes [9, 10]. In particular, studies of regulation of glucose in the non-diabetic state can give clues to pre-type 2 diabetic risk [11].

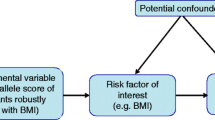

Besides social and economic factors, there may be genetic differences across humans in glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes predisposition [12]. Transethnic studies show that genetic determinants of type 2 diabetes risk or glycaemic trait levels in whites also operate in African-Americans, albeit at varying allele frequencies; thus, absolute genetic differences between racial/ethnic groups in glycaemic trait levels or disease risk are generally small [13–18]. For instance, African-American type 2 diabetes admixture mapping is consistent with an independent effect of African ancestry proportion on type 2 diabetes risk but not on diabetes-related quantitative trait levels (such as fasting glucose [FG], insulin or HbA1c) in non-diabetic individuals [12]. Under the assumption that identifying ancestral-specific variation will improve understanding of the phenotypic variation seen in type 2 diabetes and facilitate prevention efforts, we further investigated ancestry-based genetic influences on diabetes risk.

We tested the hypothesis that higher African genomic ancestry proportion is positively associated with glycaemia (FG [19] and HbA1c levels) in a population-based random sample of non-diabetic participants. In diabetes-free individuals, lack of confounding by treatment or disease duration may help reveal relatively faint genetic influences on phenotype. This approach also limits the influence of race/ethnicity-based disparities to healthcare access and subsequent type and quality of healthcare on glycaemic regulation. We expected the African ancestry–glycaemia relationship to persist even after accounting for simultaneous European and Native American genomic ancestry proportions and after further accounting for BMI and socioeconomic status (SES). Ancestry measurement used ancestry informative markers (AIMs) to create a continuous measure of African ancestry that avoids the confounding that is produced when ancestry is measured by race, a socially constructed and influenced category of ancestral self-identity.

Methods

Boston Area Community Health cohort

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey is a population-based observational study that uses a multi-stage stratified random sample to recruit adults in three racial/ethnic groups from the city of Boston [20, 21]. The third follow-up recruitment wave of this ongoing study was conducted from 2010 to 2012 and yielded a sample of 3,155 adults aged 37–88 (1,184 men and 1,971 women). During morning home interviews, trained research staff measured BMI, administered surveys that included several different indicators of SES, and collected fasting blood samples for FG and DNA for genotyping. The sampling design allowed for multiple people to be interviewed per household: 565 individuals (17.9%) were in the same household as at least one other interviewee, but there was no information with respect to relatedness. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board.

Measurements/instruments

The home visit included anthropometric measurements (i.e. height, weight and waist circumference) and an interview, conducted in English or Spanish, to obtain information about diabetes status, comorbidities, lifestyle and SES. The individual SES indicators or ‘social factors’ considered were: household income, educational attainment, occupation and health insurance status, measured at baseline. Household income, originally grouped into 12 ordinal categories, was collapsed into the following three categories: <US$20,000, US$20,000–49,999 and ≥US$50,000. Educational attainment was categorised as less than high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college, and college or advanced degree (the latter were combined due to smaller numbers). Current or former occupation was categorised according to the 2000 US census into four groups: (1) managerial, professional, sales and office occupations; (2) service occupations; (3) manual labour, which included construction, maintenance, farming, production and transportation occupations; and (4) never worked. Health insurance status was categorised as public, private or other health insurance. Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, categorised into low, moderate or high. Diet was assessed using the results of the Block Food Frequency Questionnaire classified into a seven point healthy eating score composed of sodium, vegetables, fruits, meats/beans, grains, fibre and saturated fat, largely based upon US Department of Agriculture and American Heart Association guidelines for healthy eating. A trained phlebotomist conducted the morning fasting blood draw during the home visit, including FG measured with a HemoCue 201 point-of-care analyser (HemoCue, Brea, CA, USA). HbA1c was measured using a Tina-Quant HbA1c generation 2 assay with an analytic measurement range of 3.4–18% HbA1c (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ, USA).

AIMs

Specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have widely divergent allele frequencies in ancestral populations, commonly termed AIMs, are highly informative for continental geographic ancestry. Small sets of these randomly distributed AIMs can be used to derive an accurate estimate of genetic ancestry, expressed as a proportion of each individual’s genome. For this study we analysed a panel of 62 AIMs, including 33 autosomal SNPs with allele frequencies differing by ∼82% in Native Americans vs European Americans, allowing estimation of Native American ancestry in Hispanics, and 30 SNPs discriminating West Africans from European Americans, such that with 62 uncorrelated SNPs combined we could discriminate for each individual their West African, European and Native American ancestry proportion (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1) [22, 23]. Eleven Native North and South American populations were used to define Native American AIMs [22].

High-quality genotyping was conducted at the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA, USA) using the Sequenom iPLEX platform (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA). The average call rate was 97.4%; 1.6% of samples failed quality control with call rates <90% and two SNPs failed with call rates <90%. Ancestry proportions were calculated using ADMIXTURE, (www.genetics.ucla.edu/software/admixture/; accessed 1 November 2012) with k = 3, and data were plotted using STRUCTURE (http://pritchardlab.stanford.edu/structure.html; accessed 1 November 2012) and R (version 2.15.3, accessed 21 May 2013; www.r-project.org).

Participant eligibility

From the third (January 2010 to March 2012) BACH survey cohort (n = 3,155), we excluded all individuals with missing FG, HbA1c or AIMs data, those with diagnosed diabetes (including drug- and diet-treated diabetes), and, for analyses of FG, individuals with no FG data or with FG levels > 6.94 mmol/l; for analyses of HbA1c, individuals with HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (47.5 mmol/mol) were excluded. Our final analysis cohort included 1,387 individuals (379 African-American, 411 Hispanic and 597 white). The proportion of missing data for other measures was: 19.5% for household income, 0.7% for education, 0.7% for occupation and 0.3% for BMI. To reduce bias produced by missing data [24–26], multiple imputation was implemented for exposure covariates (except for AIMs) using the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) [27] algorithm in R. Fifteen multiple imputation datasets were created. Imputations were conducted separately for each racial/ethnic group by sex combination to preserve interaction effects.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses of the association of AIMs with glycaemia were performed using SUDAAN 11 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). To account for the survey design, individuals’ clinical characteristics were weighted inversely to their probability of selection at baseline, adjusted for non-response bias at follow-up, and post-stratified to the Boston census population in 2010 [28, 29]. Ancestry proportions, FG and HbA1c levels were neither weighted nor imputed. Three-ancestry multinomial linear regression models were used to estimate y-intercepts (the FG or HbA1c level for an individual with 100% ancestry of the referent group) and regression coefficients for a 1% difference in African, Native American or European ancestry, using one of the ancestry groups as the referent and the other two as dependent variables in the models. Our primary hypothesis was that the FG slope is steeper comparing African with European ancestry, i.e. an increasing per cent African ancestry is positively associated with higher FG levels in non-diabetic individuals. We set p < 0.05 as the significance level for the primary hypothesis. We tested the HbA1c slope to confirm the FG hypothesis. Second level models tested the hypotheses that obesity or social factors weaken glycaemia–ancestry relationships. We specified three sequential models: Model 1: FG (or HbA1c) = age + sex + ancestry1 + ancestry2; Model 2: FG = age + sex + ancestry1 + ancestry2 + BMI; and Model 3: FG = age + sex + ancestry1 + ancestry2 + BMI + income + education + occupation + insurance. Physical activity and dietary behaviour could also influence ancestry–glycaemia associations, although these likely mediate the effects of BMI and social factors; nonetheless, we fitted a fourth model that added physical activity and diet score to Model 3. Finally, to evaluate the potential contribution of insulin resistance to the observed associations, we fitted Models 1–4 using fasting insulin among non-diabetic people as the dependent variable.

Results

Participants

Table 1 shows that among 1,387 non-diabetic BACH participants, there were more white than African-American individuals; Hispanic individuals were younger, poorer, less well educated and had lower employment compared with African-American or white individuals; and African-Americans had higher BMI compared with the other groups.

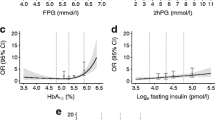

Figure 1 and Table 2 show the distribution of AIMs by self-reported race. The clustering of the blue or red dots in the corners of the triangle plot illustrates that for those self-reporting white (blue) or African-American (red) race most of the genomes were of European (93%) or African (87%) ancestry, respectively. Self-reported Hispanic participants (green dots) generally were admixed Native American (42%) or European (33%). Of 1,387 participants, 136, 40 and 1 had >99.99% European, African or Native American genetic ancestry, respectively, contributing to regression models predicting glycaemia.

The triangle (a) shows the distribution of AIMs by self-reported race. Clustering of the blue or red dots in the corners of the triangle plot for those self-reporting white (blue) or African-American (red) race show that most of their genomes were of European (93%; Table 2) or African (87%) ancestry. Self-reported Hispanic participants (green dots) were generally admixed Native American (42%) and European (33%). Individuals predicted to have 100% African genetic ancestry had 0.19 mmol/l higher FG (b) and 0.27% higher HbA1c levels (c) than those with 100% European ancestry. To convert values for HbA1c in % into mmol/mol, subtract 2.15 and multiply by 10.929

AIMs and glycaemia

Also depicted in Fig. 1 and Table 2, individuals with 100% African genetic ancestry were predicted to have 0.19 mmol/l higher FG and 0.27% higher HbA1c (%) levels than those with 100% European ancestry. For individuals in the triangle plot increasingly far from the 100% African corner, each 1% increase in European ancestry was associated with a decrease of −0.0019 mmol/l in FG (p = 0.01), and for Native American ancestry, −0.0031 mmol/l, simultaneously accounting for changes in each other’s ancestry proportion. Likewise, for HbA1c, each 1% increase in European ancestry was associated with a decrease of −0.003% HbA1c (p < 0.001), and for Native American ancestry, an increase of 0.0002% HbA1c, simultaneously accounting for changes in each ancestry proportion.

AIMs, glycaemia, obesity and indicators of SES

Table 3 shows that statistical adjustment for BMI and indicators of SES did not materially change the ancestry–glycaemia association. In Model 3, after simultaneous adjustment for Native American ancestry, age, sex, BMI, income, education, occupation and health insurance status, each 1% increase in European ancestry was associated with an FG decrease of −0.0019 mmol/l (p = 0.02); likewise, for HbA1c in adjusted models, each 1% increase in European ancestry was associated with a decrease of −0.002% HbA1c (p < 0.001). Further accounting for physical activity and dietary behaviour slightly diminished the ancestry–FG association (−0.0017, p = 0.08 per 1% increase in European ancestry; ESM Table 2) but did not materially influence the ancestry–HbA1c association (−0.0020, p < 0.001 per 1% increase in European ancestry; ESM Table 3). Although greater insulin resistance in African-Americans could alternatively explain the association of African ancestry with glycaemia, the association of African ancestry proportion and fasting insulin was weakened by adjustment for BMI (ESM Table 4), suggesting that any potential differences in insulin resistance between groups was controlled by adjustment for BMI.

Discussion

Despite increased type 2 diabetes risk in African-Americans, few genetic studies have specifically examined the association of African ancestry with hyperglycaemia and diabetes risk. It has not been clear to what extent African genomic background influences ambient glycaemia itself, behind the strong, correlated concurrent, confounding factors of obesity and SES. In a case–control analysis in Mexico City and Colombia, European ancestry proportion was associated with lower diabetes risk, and adjustment for SES substantively weakened the association [8]. Recently Cheng et al reported a large-scale admixture mapping study involving 7,021 African-Americans (2,373 with type 2 diabetes and 4,648 without), in which greater degrees of African genomic background increased the risk of type 2 diabetes, independently of adjustment for BMI and SES [12]. In individuals not receiving treatment for diabetes, African genomic background was also associated with levels of HbA1c but not FG; the HbA1c association was weakened with adjustment for BMI and SES. In the BACH Prediabetes Study we tested the hypothesis that increasing African genomic ancestry proportion is positively associated with glycaemia, taking into account comprehensive physical and social phenotyping. To test the genomic ancestry–glycaemia hypothesis we analysed only non-diabetic individuals, where weak glycaemic regulatory genetic signals may be clearer to detect due to reduced misclassification by glycaemic level associated with both untreated and treated diabetes [30, 31]. We showed that, in comparing those with 100% African vs European ancestry, African ancestry was associated with 0.19 mmol/l higher FG and 0.27% higher HbA1c levels compared with European ancestry. We showed that the African ancestry–glycaemia relationship persisted when accounting for simultaneous European and Native American genomic ancestry proportions, BMI, indicators of SES, age and sex. In models with these factors, as well as physical activity and dietary behaviour, the African–European FG gradient diminished from −0.0019 to −0.0017 mmol/l per 1% increase in per cent European ancestry, but the same gradient for HbA1c was not altered. One interpretation would be that the ancestry–FG association is slightly confounded by energy balance behaviours, after accounting for obesity and social factors. Alternatively, as physical activity and dietary behaviour are in large part the mechanisms through which BMI and social factors act, models including physical activity, diet, obesity and social factors may be over-fitted for ‘environmental’ exposures, producing over-adjusted results for genetic effects. We think the data show a clear African–European-ancestry–glycaemia gradient, even after accounting for obesity, social factors and the mediating factors of physical activity and dietary behaviour. The results provide support for previous observations that African-American genetic ancestry is associated with higher ambient glycaemia and greater type 2 diabetes risk when compared with European ancestry [4, 5, 12].

It is not yet known what specific genomic regions on the African genome confer risk for hyperglycaemia. Admixture mapping has not identified strong specific signals for type 2 diabetes risk [12, 32]. Recent biracial genome-wide association studies and meta-analyses of association datasets have shown for the most part there are more similarities than differences in African-American vs white genetic determinants of glycaemia [14–17, 32–36]. One could hypothesise that the African genome has concentrated a set of genetic variations that at one time conferred selective advantage for energy storage and survival but that are now deleterious and predispose to metabolic disease [37]. Or, overall West African genomic risk as measured here is likely not ‛African’ but rather concentrating subcontinental, clade-specific mutations, given the complex underlying clade architecture characterising the global African genome [38]. Our observation that both FG and HbA1c are higher in African ancestry argues against ancestral differences in erythrocyte biology (which may influence HbA1c measurement) having a major effect on the glycaemic/HbA1c racial differences that have been observed [39, 40]. Ongoing large-scale transethnic genomic analyses of glycaemia and erythrocyte biology will fill knowledge gaps in these areas.

Strengths of our analysis include use of a community-based random sample and early morning measurement of fasting individuals, giving a more accurate racial/ethnic prevalence of hyperglycaemia than one obtained by socially confounded reliance on individuals to visit a medical centre research facility. We focused on individuals prior to diabetes onset, an approach that reduces ‘downstream’ sources of racial/ethnic disparities that can arise from differential access to and quality of care. We used direct assessment of exposures (especially obesity) and outcomes with reliable exclusion of medical and biochemical diabetes from the analysis. SES was assessed with four separately modelled domains, allowing the full variability of income, education, occupation and insurance to be individually controlled. Thus, using a few dozen carefully selected AIMs we were able to show a robust positive association of per cent African vs per cent European genetic ancestry and glycaemia.

Our study has limitations to consider. We did not see a marked difference in glycaemia and Native American ancestry (primarily self-reported Hispanic individuals), comparing African with European ancestry. Given extensive admixture in the Hispanic group, where individuals are genetically somewhat similar to either African or European individuals, we would not expect to see strong between-group differences. There were more self-reported white individuals than African-American individuals in the sample. One might think that this could be due to preferential screening-out of diabetes among African-Americans in the sample; but, if this were true, one would expect to see lower and not higher glycaemic levels in African-Americans. Our data are cross-sectional, but genetic variation, as an exposure, can always be considered to have pre-dated most other exposures and all outcomes. Further, the cross-sectional approach characteristic of current glycaemic genetic discovery has uniformly identified variants that predict future type 2 diabetes [41]. The size of the difference between individuals with 100% African genomes and those with 100% European ancestry genomes (individuals in both groups arguably common) was ∼0.2 mmol/l or 0.27% HbA1c, both potentially clinically meaningful, potentially deleterious separations in glycaemic level. However, genetically mediated higher ambient glycaemic levels are not always associated with actual type 2 diabetes risk [42, 43]; but, to the extent that FG levels predict future type 2 diabetes, genetic variation may be one contributor to racially/ethnically noted differences in diabetes phenotypes.

In conclusion, a greater degree of African genetic ancestry proportion was independently associated with higher FG levels in a non-diabetic community-based cohort, even accounting for other ancestry proportions, obesity and indicators of SES. The results suggest that differences between African-Americans and whites in type 2 diabetes risk may include genetic or biologically mediated differences in glucose homeostasis.

Abbreviations

- AIMs:

-

Ancestry informative markers

- BACH:

-

Boston Area Community Health

- FG:

-

Fasting glucose

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

References

Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES et al (2009) Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988-1994 and 2005-2006. Diabetes Care 32:287–294

Maskarinec G, Grandinetti A, Matsuura G et al (2009) Diabetes prevalence and body mass index differ by ethnicity: the multiethnic cohort. Ethn Dis 19:49–55

Brancati FL, Kao WH, Folsom AR, Watson RL, Szklo M (2000) Incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American and white adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA 283:2253–2259

Adams AS, Zhang F, Mah C et al (2005) Race differences in long-term diabetes management in an HMO. Diabetes Care 28:2844–2849

Adams AS, Trinacty CM, Zhang F et al (2008) Medication adherence and racial differences in A1c control. Diabetes Care 31:916–921

Boltri JM, Okosun IS, Davis-Smith M, Vogel RL (2005) Hemoglobin A1c levels in diagnosed and undiagnosed black, Hispanic, and white persons with diabetes: results from NHANES 1999-2000. Ethn Dis 15:562–567

Geiss LS, James C, Gregg EW, Albright A, Williamson DF, Cowie CC (2010) Diabetes risk reduction behaviors among U.S. adults with prediabetes. Am J Prev Med 38:403–409

Florez JC, Price AL, Campbell D et al (2009) Strong association of socioeconomic status with genetic ancestry in Latinos: implications for admixture studies of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 52:1528–1536

Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB et al (2004) The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med 140:945–950

Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP (2001) The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA 286:1195–1200

Ingelsson E, Langenberg C, Hivert MF et al (2010) Detailed physiologic characterization reveals diverse mechanisms for novel genetic loci regulating glucose and insulin metabolism in humans. Diabetes 59:1266–1275

Cheng CY, Reich D, Haiman CA et al (2012) African ancestry and its correlation to type 2 diabetes in African Americans: a genetic admixture analysis in three U.S. population cohorts. PLoS One 7:e32840

Morris AP (2011) Transethnic meta-analysis of genomewide association studies. Genet Epidemiol 35:809–822

Waters KM, Stram DO, Hassanein MT et al (2010) Consistent association of type 2 diabetes risk variants found in Europeans in diverse racial and ethnic groups. PLoS Genet 6:e1001078

Yang Q, Liu T, Shrader P et al (2010) Racial/ethnic differences in association of fasting glucose-associated genomic loci with fasting glucose, HOMA-B, and impaired fasting glucose in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care 33:2370–2377

Ng MC, Saxena R, Li J et al (2013) Transferability and fine mapping of type 2 diabetes loci in African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource Plus Study. Diabetes 62:965–976

Liu CT, Ng MC, Rybin D et al (2012) Transferability and fine-mapping of glucose and insulin quantitative trait loci across populations: CARe, the Candidate Gene Association Resource. Diabetologia 55:2970–2984

Fesinmeyer MD, Meigs JB, North KE et al (2013) Genetic variants associated with fasting glucose and insulin concentrations in an ethnically diverse population: results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) study. BMC Med Genet 14:98

Lofgren P, van Harmelen V, Reynisdottir S et al (2000) Secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha shows a strong relationship to insulin-stimulated glucose transport in human adipose tissue. Diabetes 49:688–692

McKinlay JB, Link CL (2007) Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol 52:389–396

Piccolo RS, Araujo AB, Pearce N, McKinlay JB (2014) Cohort profile: The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Int J Epidemiol 43:42–51

Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA et al (2004) A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet 74:1001–1013

Price AL, Patterson N, Yu F et al (2007) A genomewide admixture map for Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet 80:1024–1036

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, New York

Little RJA, Rubin DB (2002) Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley, New York

Schafer J (1997) Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman & Hall, New York

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45:1–67

Cochran W (1977) Sampling techniques, 3rd edn. Wiley, New York

Heeringa S, West BT, Berglund PA (2010) Applied survey data analysis. CRC, Boca Raton

Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Alonso A, Li M et al (2010) Impact of repeated measures and sample selection on genome-wide association studies of fasting glucose. Genet Epidemiol 34:665–673

Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I et al (2010) New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 42:105–116

Elbein SC, Das SK, Hallman DM, Hanis CL, Hasstedt SJ (2009) Genome-wide linkage and admixture mapping of type 2 diabetes in African American families from the American Diabetes Association GENNID (Genetics of NIDDM) study cohort. Diabetes 58:268–274

Lewis JP, Palmer ND, Hicks PJ et al (2008) Association analysis in African Americans of European-derived type 2 diabetes single nucleotide polymorphisms from whole-genome association studies in African Americans. Diabetes 57:2220–2225

Chen G, Bentley A, Adeyemo A et al (2012) Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci association with fasting insulin and insulin resistance in African Americans. Hum Mol Genet 21:4530–4536

Palmer ND, McDonough CW, Hicks PJ et al (2012) A genome-wide association search for type 2 diabetes genes in African Americans. PLoS One 7:e29202

Haiman CA, Fesinmeyer MD, Spencer KL et al (2012) Consistent directions of effect for established type 2 diabetes risk variants across populations: the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Consortium. Diabetes 61:1642–1647

Lazar MA (2005) How obesity causes diabetes: not a tall tale. Science 307:373–375

Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR et al (2009) The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science 324:1035–1044

Soranzo N, Sanna S, Wheeler E et al (2010) Common variants at ten genomic loci influence hemoglobin A1c levels via glycemic and non-glycemic pathways. Diabetes 59:3229–3239

Maruthur NM, Kao WH, Clark JM et al (2011) Does genetic ancestry explain higher values of glycated hemoglobin in African Americans? Diabetes 60:2434–2438

de Miguel-Yanes JM, Shrader P, Pencina MJ et al (2011) Genetic risk reclassification for type 2 diabetes by age below or above 50 years using 40 type 2 diabetes risk single nucleotide polymorphisms. Diabetes Care 34:121–125

Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP et al (2012) Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet 44:991–1005

Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM et al (2012) Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 44:981–990

Funding

This study was supported by NIDDK R01 DK080786 ‘Upstream contributors to downstream disparities in type 2 diabetes’, as well as by NIDDK K24 DK080140 and R01 DK078616 (JBM).

Duality of interest

The authors have no dualities of interest to disclose.

Contribution statement

JBM and JBMc made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. RWG, LL, JCF and LM made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and interpretation of data, and critically revised the article for important intellectual content. RP and BP made substantial contributions to the study design, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. JBM is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 55 kb)

ESM Table 2

(PDF 96 kb)

ESM Table 3

(PDF 94 kb)

ESM Table 4

(PDF 96 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meigs, J.B., Grant, R.W., Piccolo, R. et al. Association of African genetic ancestry with fasting glucose and HbA1c levels in non-diabetic individuals: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Prediabetes Study. Diabetologia 57, 1850–1858 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3301-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3301-1