Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We tested the hypothesis that age younger than 65 years at type 2 diabetes diagnosis is associated with worse subsequent glycaemic control.

Methods

A cross-sectional analysis of data from participants in the 2005–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey was performed. For adults with self-reported diabetes, we dichotomised age at diabetes diagnosis as younger (<65 years) vs older (≥65 years). The primary outcome of interest was HbA1c >9.0% (75 mmol/mol). Secondary outcomes were HbA1c >8.0% (64 mmol/mol) and >7.0% (53 mmol/mol). We used multivariable logistic regression for analysis.

Results

Among 1,438 adults with diabetes, a higher proportion of those <65 years at diagnosis compared with those ≥65 at diagnosis had an HbA1c >9.0% (14.4% vs 2.5%, p < 0.001). After adjustment for sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance, usual source of care, hyperglycaemia medication, duration of diabetes, family history, BMI and waist circumference, age <65 years at diagnosis remained significantly associated with greater odds of HbA1c >9.0% (OR 3.22, 95% CI 1.54, 6.72), HbA1c >8.0% (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.43, 5.16) and HbA1c >7.0% (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.18, 3.11). The younger group reported fewer comorbidities, but were less likely to report good health (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36, 0.83).

Conclusions/interpretation

Younger age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis is significantly associated with worse subsequent glycaemic control. Because patients who are younger at diagnosis have fewer competing comorbidities and complications, safe, aggressive, individualised treatment could benefit this higher-risk group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient-centredness is a priority in type 2 diabetes care [1]. With increasing recognition that the benefits and burdens of treatment differ by patient population, identifying subgroups at high risk of poor outcomes is an important goal, which may facilitate population management for diabetes. In this sense, different ‘phenotypes’ of type 2 diabetes may identify populations that may need and benefit from more intensive interventions.

Mounting evidence suggests that those with onset of type 2 diabetes in early or mid-adult life, compared with those with onset at an older age (65 or older), may have a more severe disease course, with increased risk of microvascular complications and worse glycaemic control [2–5]. While these differences in severity of dysglycaemia may be due to known risk factors such as longer duration of diabetes and higher BMI, they may also reflect more significant insulin deficiency in those diagnosed at younger ages. In this study we tested the hypothesis that those diagnosed at a younger age would have worse glycaemic control, even after adjustment for duration of diabetes, higher BMI and other known risk factors for worse glycaemic control.

Methods

Data source and study sample

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis combining three cycles of the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is a series of epidemiological surveillance surveys conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in community-dwelling participants [6]. Trained interviewers meet participants in their homes and administer a structured questionnaire in English, Spanish or with an interpreter. Participants then travel to a mobile examination centre (MEC) for physical examination and blood draws for laboratory analysis. Data are collected in 2-year cycles, which can be pooled to allow ascertainment of a larger number of cases. For this analysis, we pooled cycles in order to have enough participants diagnosed with diabetes at an older age and to allow robust adjustment for potential confounders. Full methodological details of NHANES have been previously published [6].

Our study included all adult (age >20 years) NHANES participants from 2005–2010 with diabetes [7]. We excluded participants who were pregnant at the time of examination. To minimise inclusion of type 1 diabetes patients, we excluded patients who were diagnosed before the age of 30 and started on insulin around the time of diagnosis. This approach is in accordance with previous evaluations of NHANES data [8, 9]. A participant was considered to have diabetes if he or she answered ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or healthcare professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?’ This method has been used in previous studies [10–12] and CDC publications [13]. Sensitivity of this measure has been reported to be >95% in previous NHANES analyses [9], and specificity has been reported to be as high, at 97% [11]. We did not include participants with biochemical but not self-reported diabetes because age at diagnosis could not be determined in these cases.

The Partners HealthCare Human Research Committee exempted this study from institutional review board review.

Measures

Age at diabetes onset

For this study, we dichotomised age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis as occurring in younger adult life (age <65 years) compared with older adult life (age ≥65 years) based on patient self-report. This dichotomisation was based on previous observations of differential effects of diabetes on health status by age in this range [3, 14]. In exploratory analyses, we also treated age at diagnosis as a continuous variable.

Outcomes

We used HbA1c percentage as a measure of glycaemic control. Our primary outcome of interest was whether the HbA1c value was >9.0% (75 mmol/mol), which represents out-of-control hyperglycaemia for all patients [15]. In order determine whether glycaemic control was worse at other commonly used thresholds [15], we conducted secondary analyses using outcomes of HbA1c above or below 8.0% (64 mmol/mol) and 7.0% (53 mmol/mol).

To determine whether age at diabetes diagnosis was associated with comorbidity, we used responses on previously validated self-report items [6] for end stage renal disease (ESRD), current asthma diagnosis, congestive heart failure (CHF), CHD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and history of malignancy of any kind. We also considered the health status of patients with the question ‘Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?’. We dichotomised this question into good (excellent, very good or good) vs poor (fair or poor) health [14]. Response to this item correlates highly with a range of health outcomes [16–20].

Demographic and socioeconomic variables

We considered several demographic and socioeconomic variables that might be associated with age of diabetes onset and glycaemic control. Demographic variables included sex and race/ethnicity (self-report categorised as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or other, including multiracial). Socioeconomic covariates included income expressed as percentage of the federal poverty level (which accounts for inflation across the study period and for differences in household size), educational attainment (less than high school diploma, high school diploma, some college or higher) and insurance status (categorised as no insurance, private insurance, Medicare or other public insurance [including Medicaid, as well as Medicare and Medicaid Dual eligible participants]).

Clinical variables

We considered several clinical variables thought to be associated with worse glycaemic control as covariates. Having a usual place of care was dichotomised to ‘yes’/‘no’, and BMI (weight in kg divided by height in m2) was categorised as ‘underweight’ (<18.5 kg/m2), ‘normal’ (18.5–25.0 kg/m2), ‘overweight’ (>25.0–30.0 kg/m2) and ‘obese’ (>30.0 kg/m2). To account for visceral obesity, which may be more closely associated with hyperglycaemia than BMI [21, 22], we also included measured waist circumference (continuous). Duration of diabetes was calculated from the patient’s report of age at diabetes diagnosis subtracted from current age. Diabetes treatment was classified into categories of no medication, metformin only, sulfonylurea only, mixed oral medications or insulin (with or without any other medications). We also adjusted for self-report of a ‘close biological’ relative (i.e. father, mother, sister and/or brother) with diabetes.

Statistical analysis

We conducted an analysis of cross-sectional data. First, we performed descriptive statistics on the sample, using χ 2 tests to evaluate differences in categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. We then performed multivariable logistic regression in order to determine the independent association of age at diabetes diagnosis with HbA1c >9.0%, adjusting for the demographic, socioeconomic and clinical factors described. Age at time of study was not directly included because it is a function of age at diagnosis and duration of diabetes. We then conducted secondary analyses to determine if age at diagnosis was also associated with increased risk of having HbA1c >8.0% or HbA1c >7.0%, as well as whether age at diagnosis, as a continuous variable, was associated with HbA1c >9.0%, adjusting for the same factors as above.

In general, individuals who are older at diagnosis have higher mortality than those diagnosed at younger ages because of their more advanced age. If more severe diabetes further increases this risk, then a survival bias, where more mild cases of diabetes in patients older at diagnosis predominate, could occur. To account for this, we conducted two sensitivity analyses in restricted populations, using multivariable logistic regression with an outcome of HbA1c >7.0% (chosen because it allowed enough outcomes to permit adjustment for the same covariates as the primary analysis in this restricted population). First, we restricted analysis to patients older than 70 at the time of examination. This strategy will yield a conservative estimate of the effect of younger age at diagnosis, as it will include only those patients who have survived a significant amount of time with diabetes. Second, because there is little diabetes-specific mortality in the first 5 years of diagnosis [23], and thus less opportunity for survival bias to arise, we also conducted an analysis restricted to patients with diabetes of <5 years’ duration.

Finally, because those on insulin can be thought of as representing the most ‘severe’ cases of type 2 diabetes, we also fitted a multivariable linear regression model to compare mean HbA1c among this more homogeneous subset. The purpose of this analysis was to test the hypothesis that, even in participants with the most severe insulin deficiency, younger age at diabetes diagnosis is associated with more severe hyperglycaemia.

We used SAS survey procedures (version 9.3; Cary, NC, USA) and SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 10.0.1; Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) for analysis to account for the complex multistage survey design. In accordance with CDC recommendations [6], we used 6-year MEC weights in our analysis. A p value of <0.05 on χ 2 or F tests was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Results

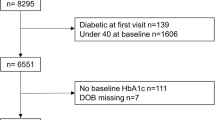

There were 1,922 adult NHANES examination participants who reported diabetes. After exclusions, 1,438 participants remained in the study sample. An equivalent proportion of participants were excluded from each age-at-diagnosis group (p = 0.34). Almost 84% (n = 1,166) were diagnosed with diabetes before age 65. Patients diagnosed with diabetes before age 65 were more likely to be younger at the time of study, non-white, uninsured, obese, and have longer duration of diabetes. Table 1 presents full characteristics of the study sample.

Overall, 12.5%, 20.9% and 44.3% of participants had an HbA1c >9.0%, 8.0% and 7.0%, respectively. Patients who were younger at diagnosis were more likely to have an HbA1c >9.0% (14.4% vs 2.5%, p < 0.001), HbA1c >8.0% (23.7% vs 6.2%, p < 0.001) and HbA1c >7.0% (47.9% vs 25.6%, p < 0.001). Figure 1 depicts comparisons at each glycaemic control threshold. After adjustment for sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance, usual source of care, hyperglycaemia medication, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, BMI and waist circumference, younger, compared with older, age at diagnosis remained significantly associated with greater odds of HbA1c >9.0% (OR 3.22, 95% CI 1.54, 6.72). In secondary analyses adjusted for the same covariates, younger, compared with older, age at diagnosis was also associated with greater odds of an HbA1c >8.0% (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.43, 5.16) and HbA1c >7.0% (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.18, 3.11). Table 2 presents full results for the multivariable logistic regression models of glycaemic control.

Proportion of patients above HbA1c threshold by age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Black bars, <65 years; white bars, ≥65 years. To convert values for HbA1c in % to mmol/mol, subtract 2.15 and multiply by 10.929, or use the conversion calculator at www.HbA1c.nu/eng/

We next conducted analyses treating age as a continuous variable. Figure 2 depicts the correlation between age at diagnosis and HbA1c at the time of study, showing that current HbA1c decreases as age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis increases. In a multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for the same covariates as above, each 1 year increase in age at diagnosis was associated with decreased odds of having an HbA1c >9.0% (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.93, 0.96).

Age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis and current HbA1c. Dashed line, 95% CI; solid line, trendline. To convert values for HbA1c in % to mmol/mol, subtract 2.15 and multiply by 10.929, or use the conversion calculator at www.HbA1c.nu/eng/

In multivariable logistic regression sensitivity analyses meant to minimise the possible effect of survival bias, younger age at diagnosis was associated with increased odds of HbA1c >7.0%, adjusted for the same potential confounders as above, in analyses restricted to those over age 70 years (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.35, 5.50) and in those with diabetes of <5 years’ duration (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.01, 3.61). The number of cases in this dataset was insufficient to fit multivariable logistic regression models for outcomes of HbA1c >8.0% or >9.0%, but the unadjusted results were similar and supported the hypothesis that younger age at diagnosis is associated with worse glycaemic control (data not shown).

Restricting the analysis to patients on insulin in order to identify the most severe cases of type 2 diabetes, patients younger at diagnosis had higher mean HbA1c than those older at diagnosis (8.2% [66 mmol/mol] vs 7.3% [56 mmol/mol], p = 0.006). Even after adjustment for sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance, usual source of care, diabetes medication, duration of diabetes, BMI and waist circumference, those of younger age at diagnosis on insulin had a higher adjusted mean HbA1c (8.8% [73 mmol/mol] vs 7.8% [62 mmol/mol], p = 0.01).

In order to understand the context of overall medical illness and health status in the two groups, we next conducted analyses of comorbidity and health status. Those younger at diagnosis were less likely to report being in good health (56.7% vs 67.7%, p < 0.001), despite also being less likely to report CHF (8.5% vs 16.7%, p < 0.001), CHD (17.6 vs 30.5, p < 0.001), CVA (8.7% vs 17.5%, p < 0.001) and cancer (12.0 vs 29.0, p < 0.001). Table 3 reports further results for comorbidities. In a multivariable logistic regression model, after adjustment for sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance, usual source of care, diabetes medication, duration of diabetes, BMI, waist circumference and history of asthma, CHD, CHF, COPD, CVA, malignancy and ESRD, those younger at diagnosis were significantly less likely to report being in good health (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36, 0.83).

Discussion

In this analysis of a nationally representative sample of adults with diabetes, younger age at diabetes onset was associated with poor glycaemic control at every relevant threshold. Although those younger at diagnosis did have higher average BMI and longer average duration of diabetes, these factors did not explain the observed association between age at diagnosis and glycaemic control. Results of sensitivity analyses to account for the effect of any survivor bias did not alter this conclusion. Those younger at diagnosis also had more intense diabetes treatment, as evidenced by greater use of multiple oral medications or insulin.

The association between younger age at diabetes diagnosis and glycaemic control persisted despite adjustment for race/ethnicity, insurance, income and educational attainment. This suggests that differences in physiology and care access and usage patterned by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status do not fully explain the observed association between age at diagnosis and glycaemic control. However, differences in race/ethnicity, insurance and socioeconomic status between those younger and older at diagnosis remain important for management of diabetes, as they may affect effectiveness, risk of harm, availability and uptake of interventions.

Those with a younger age at diabetes diagnosis were significantly less likely to report being in good health, despite having fewer other major medical problems. This suggests that diabetes is an important factor driving poor health in this group. In contrast with those older at diabetes diagnosis, for whom diabetes is only one of many medical issues and who may have already suffered many of the complications that diabetes treatment attempts to avert, prioritising diabetes treatment for those younger at diagnosis may have greater benefit in improving health and averting long-term complications.

One concern in interpreting these results may be whether the younger-at-diagnosis group includes a higher proportion of type 1 diabetes patients. We minimised inclusion of these patients using a strategy previously used in NHANES analyses. In addition, the observation that there is significantly more obesity by both BMI and waist circumference in the younger-at-diagnosis group is not consistent with an increased prevalence of type 1 diabetes in the younger age group.

Our work is consistent with, and extends the results of, previous studies. A previous study [14] demonstrated that diabetes was more harmful to perceptions of health in younger patients, but did not address whether age at diagnosis is an important indicator of diabetes severity. Selvin et al [3], in a study of patients ≥65 years of age only, noted increased hyperglycaemia in those diagnosed at a younger age. However, factors that may have mediated the observed hyperglycaemia were not examined. Wong et al [5] observed an increased risk of retinopathy in diabetes patients who were younger at diagnosis, independently of hyperglycaemia, suggesting underlying physiological differences in groups by age at diagnosis, which our analysis supports.

While our results showing that differences in hyperglycaemia between age-at-diagnosis groups were not explained by treatment intensity, BMI and waist circumference as a measure of visceral obesity are consistent with an underlying physiological difference, the limitations of the dataset do not permit further investigation of pathophysiological correlates of this finding, such as beta cell function and insulin resistance. In addition, observed differences may be due to processes of care factors such as treatment adherence, visit frequency and care engagement, which were not measured, other than having a regular place to receive care. Because NHANES studies only community-dwelling Americans, our data probably overestimate the percentage of total diabetes patients diagnosed at a younger age, as older adults diagnosed in long-term care are not included. Finally, the data are cross-sectional, and a causal conclusion regarding age at diagnosis and subsequent diabetes control cannot be drawn.

These limitations are balanced by several strengths. We present results from a nationally representative dataset with standardised ascertainment of interview, physical examination and laboratory data by trained personnel using well-validated methods. We adjusted for a robust set of potential confounders including obesity, treatment and duration of diabetes, and our sensitivity analyses revealed similar results to the main analysis.

In a further study of the relevance of age at diabetes diagnosis, longitudinal research will be helpful in determining whether the observed differences in cross-sectional measures seen here actually represent a more severe diabetes course with worse hyperglycaemia requiring more intensive treatment and increased risk of age-adjusted adverse outcomes such as chronic kidney disease or CHD. This may also help delineate whether observed differences are attributable to different underlying physiology, differences in care processes, a survival effect or other factors.

In conclusion, younger age at diabetes diagnosis is strongly associated with subsequent hyperglycaemia compared with older age at diabetes diagnosis, which is not explained by differences in BMI, duration of disease, or treatment. Further longitudinal research to help clarify differences in disease course is needed. In the meantime, because patients who are younger at diagnosis have fewer competing comorbidities and complications, safe yet aggressive, individualised treatment may lead to important benefits in this higher-risk group.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVA:

-

Cerebrovascular accident

- ESRD:

-

End stage renal disease

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

References

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al (2012) Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 55:1577–1596

O'Connor PJ, Desai JR, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Bishop DB (2003) Variation in diabetes care by age: opportunities for customization of care. BMC Fam Pract 4:16

Selvin E, Coresh J, Brancati FL (2006) The burden and treatment of diabetes in elderly individuals in the U.S. Diabetes Care 29:2415–2419

Shorr RI, Franse LV, Resnick HE, Di Bari M, Johnson KC, Pahor M (2000) Glycemic control of older adults with type 2 diabetes: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:264–267

Wong J, Molyneaux L, Constantino M, Twigg SM, Yue DK (2008) Timing is everything: age of onset influences long-term retinopathy risk in type 2 diabetes, independent of traditional risk factors. Diabetes Care 31:1985–1990

CDC (2012) Continuous NHANES tutorial. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/Nhanes/index_continuous.htm, accessed 8 November 2012

CDC (2012) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm, accessed 21 March 2013

Koopman RJ, Mainous AG 3rd, Diaz VA, Geesey ME (2005) Changes in age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States, 1988 to 2000. Ann Fam Med 3:60–63

Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB (2007) Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2002. J Gen Intern Med 22:1018–1023

Midthjell K, Holmen J, Bjorndal A, Lund-Larsen G (1992) Is questionnaire information valid in the study of a chronic disease such as diabetes? The Nord-Trondelag Diabetes Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 46:537–542

Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, Chylack LT Jr (1994) Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol 139:813–818

Heliovaara M, Aromaa A, Klaukka T, Knekt P, Joukamaa M, Impivaara O (1993) Reliability and validity of interview data on chronic diseases. The Mini-Finland Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 46:181–191

Ali MK, McKeever Bullard K, Imperatore G, Barker L, Gregg EW (2012) Characteristics associated with poor glycemic control among adults with self-reported diagnosed diabetes: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2007-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 61(Suppl):32–37

Wexler DJ, Porneala B, Chang Y, Huang ES, Huffman JC, Grant RW (2012) Diabetes differentially affects depression and self-rated health by age in the U.S. Diabetes Care 35:1575–1577

American Diabetes Association (2013) Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2013. Diabetes Care 36(Suppl 1):S11–S66

Bowling A (2005) Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health 59:342–345

Goldstein MS, Siegel JM, Boyer R (1984) Predicting changes in perceived health status. Am J Public Health 74:611–614

Idler EL, Kasl SV (1995) Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 50:S344–S353

Kaplan GA, Camacho T (1983) Perceived health and mortality: a nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. Am J Epidemiol 117:292–304

Manor O, Matthews S, Power C (2001) Self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness: inter-relationships with morbidity in early adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 30:600–607

Blaha MJ, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Elasy TA (2008) Waist circumference, not the metabolic syndrome, predicts glucose deterioration in type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16:869–874

Manjoo P, Joseph L, Dasgupta K (2012) Abdominal adiposity and daily step counts as determinants of glycemic control in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Diabetes 2:e25

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA (2008) 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 359:1577–1589

Funding

SAB was supported by an institutional National Research Service Award T32HP10251, the Ryoichi Sasakawa Fellowship Fund, and by the General Medicine Division at Massachusetts General Hospital. DJW receives funding from the National Institutes of Health under award R03DK090196. JBM is supported in part by K24 DK080140. The funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, or the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

SAB, DJW and JBM conceptualised and designed the study and interpreted the analyses. SAB performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. DJW and JBM revised the manuscript for critical intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. SAB had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. He will serve as the guarantor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berkowitz, S.A., Meigs, J.B. & Wexler, D.J. Age at type 2 diabetes onset and glycaemic control: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2010. Diabetologia 56, 2593–2600 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-3036-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-3036-4