Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Successful postprandial glycaemia management requires understanding of absorption patterns after meals containing variable complex carbohydrates. We studied eight young participants with type 1 diabetes to investigate a large low-glycaemic-load (LG) meal and another eight participants to investigate a high-glycaemic-load (HG) meal matched for carbohydrates (121 g).

Methods

On Visit 1, participants consumed an evening meal. On follow-up Visit 2, a variable-target glucose clamp was performed to reproduce glucose and insulin levels from Visit 1. Adopting stable-label tracer dilution methodology, we measured endogenous glucose production on Visit 2 and subtracted it from total glucose appearance measured on Visit 1 to obtain meal-attributable glucose appearance.

Results

After the LG meal, 25%, 50% and 75% of cumulative glucose appearance was at 88 ± 21, 175 ± 39 and 270 ± 54 min (mean ± SD), whereas glucose from the HG meal appeared significantly faster at 56 ± 12, 100 ± 25 and 153 ± 39 min (p < 0.001 to 0.003), and resulted in a 50% higher peak appearance (p < 0.001). Higher apparent bioavailability by 15% (p = 0.037) was observed after the LG meal. We documented a 20 min deceleration of dietary mixed carbohydrates compared with dietary glucose for the HG meal and a twofold deceleration for the LG meal.

Conclusions/interpretation

Absorption patterns may be influenced by glycaemic load and/or meal composition, affecting optimum prandial insulin dosing in type 1 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In type 1 diabetes, modern approaches to management of postprandial glycaemia include carbohydrate counting [1], the use of bolus calculators [2] and administering rapid-acting insulin analogues [3] timed according to meal type and prevailing glycaemia [4–7]. Gauging of prandial insulin aims to ameliorate elevated postprandial glucose levels, which correlate strongly with HbA1c [8], while reducing the risk of postprandial hypoglycaemia.

Informed by clinical observations, these management approaches lack mechanistic understanding of absorption patterns of commonly eaten meals containing complex carbohydrates. Using tracer dilution methodology [9], early investigations documented persistent abnormalities in glucose load absorption in type 1 diabetes [10, 11], and these were followed by studies documenting absent effects of hyperglycaemia [12] and insulin [13] on gastric emptying and glucose absorption. However, methodological challenges deterred investigation of meals containing non-glucose carbohydrates.

The common notion is that glucose is absorbed differently from other simple sugars and complex carbohydrates, and, although experimental proof in type 1 diabetes is missing, this has prevented assessment of common meals, with the exception of maize or wheat naturally or artificially enriched with 13C and studied in healthy participants [14–16] but not in type 1 diabetes.

In addition to obtaining mechanistic information to inform postprandial glycaemia management, the present study is motivated by research on overnight closed-loop insulin delivery in young people and our interest in absorption of large evening meals, which may complicate safe and efficacious closed-loop control [17]. In this study, we combine an innovative experimental design with advanced, validated calculations to evaluate the systemic appearance of glucose after evening meals containing glucose and non-glucose carbohydrates. We contrast two representative high- and low-glycaemic-load meals matched for total carbohydrates but differing in fat and protein content to investigate the spectrum of absorption patterns.

Methods

Study participants

Eight young participants with type 1 diabetes were enrolled to investigate a low-glycaemic-load (LG) meal. Another eight participants were enrolled to investigate a high-glycaemic-load (HG) meal. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were 16–24 years old. Inclusion criteria were type 1 diabetes for at least 6 months (WHO criteria or confirmed negative C-peptide), multiple daily injections or pump therapy, BMI <30 kg/m2 and HbA1c <12% (108 mmol/mol). Exclusion criteria were a total daily insulin dose >1.4 U/kg body weight, gastroparesis, pregnancy and intention to become pregnant.

Experimental procedures

Participants were admitted to the Wellcome Trust clinical research facility (Cambridge) on two occasions between 1 and 3 weeks (up to 5 weeks for two participants) apart. Those receiving multiple daily injections (LG meal, n = 5; HG meal, n = 7) stopped basal insulin at least 12 h before admission. Symptomatic hypoglycaemia within the preceding 48 h or moderate or intense exercise within the preceding 24 h led to the study visit being rescheduled.

On Visit 1, participants consumed an LG or HG meal. On Visit 2, no meal was consumed but a variable-target glucose clamp was performed to reproduce the glucose and insulin levels obtained on Visit 1. Using stable-label tracer dilution methodology, endogenous glucose production (EGP) measured on Visit 2 was subtracted from total glucose appearance estimated on Visit 1 to derive meal-attributable glucose appearance resulting from absorption of dietary glucose, breakdown of complex carbohydrates, and gluconeogenesis from dietary precursors (Fig. 1).

Meal-attributable glucose appearance includes dietary glucose and glucose released from breakdown of complex carbohydrates. It also includes glucose produced by gluconeogenesis from dietary precursors such as simple sugars and amino acids (circled 1), which is distinct from EGP independent of these precursors (circled 2). Total glucose appearance is the sum of all glucose sources

Common procedures during Visit 1 and Visit 2

Study procedures are outlined in Fig. 2. Participants were admitted after breakfast. From 10:00 to 17:30 hours, they fasted, and i.v. insulin (Actrapid, Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) titrated every 15 min was infused to achieve a plasma glucose concentration of 6.0 mmol/l. After 17:30 hours, insulin delivery was matched on Visits 1 and 2 and consisted of a constant basal i.v. insulin infusion and variable i.v. delivery. The latter was initiated at 18:00 hours to mimic systemic insulin appearance resulting from a subcutaneous bolus of rapid-acting insulin analogue. The delivery pattern of variable insulin followed a two-compartment chain with time-to-maximum absorption of 50 min [18] with percentage rates of 25, 60, 81, 94, 100, 100, 96, 91, 85, 77, 70, 62, 57, 49, 43, 38, 34, 28, 25, 21, 19, 15, 13, 11, 9, 8, 6, 4, 2 and 0 of the maximum infusion rate at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120, 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, 180, 190, 200, 210, 220, 230, 240, 250, 270, 290, 320 and 390 min after 18:00 hours. The total amount of variable insulin was calculated using individualised insulin/carbohydrate ratios for meals containing 121 g carbohydrates.

A primed constant continuous i.v. infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose (6 mg/kg prime; 0.06 mg kg−1 min−1 continuous infusion; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA, USA) was given over 150 min from 15:30 hours. From 18:00 hours, the infusion rate was altered in a manner that mimicked the expected post-meal suppression of EGP; [6,6-2H2]glucose was infused at a rate of 70%, 60%, 50%, 35%, 45%, 50%, 55%, 65% and 70% (100% represents the rate of 0.06 mg kg−1 min−1) at 0, 10, 20, 30, 220, 240, 280, 300 and 400 min after 18:00 hours.

From 18:00 hours, [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) was infused in a manner that mimicked the expected glucose appearance from a standard meal; [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose was infused at 20%, 40%, 55%, 70%, 90%, 100%, 90%, 70%, 50%, 40%, 30%, 20%, 10%, 5% and 0% of 0.1 mg kg−1 min−1 at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 90, 120, 150, 180, 195, 225, 270, 330 and 405 min after 18:00 hours.

Visit 1: meal consumption

At 18:00 hours, eight participants consumed an LG meal (macaroni cheese; glycaemic load 54), while the other eight consumed an HG meal (vegetable shepherd’s pie; glycaemic load 105). Glycaemic index/load was determined by an experienced diabetes dietitian. Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1 shows the detailed meal contents. The two meals were eaten over 20 min and matched for carbohydrates but not protein, fat or energy (carbohydrates/protein/fat 121:35:31 vs 121:20:9 g; 899 vs 615 kcal). The meals were enriched with 1.7 g [U-13C]glucose, dissolved in a small bottle with tepid water, bottle rinsed, content mixed in a serving bowl within the sauce before the bulk was added, and a bread slice used to clean the bowl at the end of the meal.

Visit 2: variable-target glucose clamp

From 18:00 hours, a variable i.v. 20% dextrose infusion enriched with [U-13C]glucose (13 mg/g) was infused over 8 h to replicate the individual post-meal plasma glucose excursions observed on Visit 1. An adaptive model predictive controller (gMPC, Version 1.0.2, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) was used to adjust the dextrose infusion using information about the participant’s total daily insulin dose, the i.v. insulin delivery, and the target glucose profile.

From 10:00 hours during both visits, venous blood samples were taken every 10–15 min for the determination of plasma glucose. Samples were taken at 15:00, 15:15 and 15:30 hours to determine background glucose enrichments. From 17:00 hours, venous blood samples were taken every 10–30 min for the determination of plasma insulin, triacylglycerols, [U-13C]glucose, [6,6-2H2]glucose and [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose. The samples were immediately centrifuged and separated. Plasma glucose was measured immediately, while other samples were stored at −80°C until assayed.

Assays

Plasma glucose was measured using a YSI2300 STAT Plus Analyser (YSI, Lynchford House, Farnborough, UK). Plasma insulin was measured using an immunochemiluminometric assay (Invitron, Monmouth, UK) with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 4.7% and an interassay coefficient of variation of 7.2–8.1%. Plasma triacylglycerols were measured using an enzymatic assay (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with an interassay coefficient of variation of 5.5% at 0.9 mmol/l and 3.4% at 2.4 mmol/l. Plasma samples were derivatised to form the methoxime-trimethylsilyl derivative for gas chromatography MS analysis (Agilent 5975C inert XL EI/CI MSD; Agilent Technologies, Wokingham, UK) to measure ions m/z 319.2 (M + 0), 321.2 (M + 2), 322.2 (M + 3), 323.2 (M + 4), 324.2 (M + 5) and 327.2 (M + 8) [19].

Data analysis

Tracer/tracee ratio

Tracer/tracee ratios were calculated using a variation of the method described previously [20, 21]. In brief, ions m/z M + 0, M + 2, M + 4 and M + 8 were used to calculate tracer/trace ratios of [6,6-2H2]glucose, [U-13C]glucose and [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose corrected for recycled glucose using ions m/z M + 0, M + 3 and M + 5. The calculations accounted for spectra overlap [22]. It was assumed that [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose is recycled equally into glucose molecules with m/z of M + 4 and M + 5 and that [U-13C]glucose is recycled equally into glucose molecules with m/z of M + 2 and M + 3 [23, 24]. A system of algebraic equations was solved analytically, solution reduced and validated using Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL, USA). The endogenous glucose concentration was calculated using a model-independent method as described previously [25].

Modelling glucose kinetics

A stochastic modelling approach was used to estimate glucose turnover, adopting a hierarchical Bayes model implementing the Radziuk/Mari two-compartment model of glucose kinetics [26, 27]. The method used Bayesian inference with a regularising prior distribution that assumes smooth glucose fluxes [20] with individualised smoothness levels drawn from a population distribution [28]. The method has been described previously [29] and validated against data collected on Visit 2 [30].

Total glucose appearance (R a total ) and glucose disposal were estimated on Visits 1 and 2 from plasma glucose, [6,6-2H2]glucose and [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose. On Visit 1, total glucose appearance represents the sum of meal-attributable glucose appearance (R a meal ) and the dietary-precursor-independent component of EGP (Fig. 1). Using endogenous glucose concentration and [6,6-2H2]glucose, we estimated the dietary-precursor-independent component endogenous glucose concentration from data collected on Visit 2 and subtracted it from the total appearance obtained on Visit 1 to derive the meal-attributable glucose appearance, i.e.

where superscript indicates that the quantity was estimated from data collected on Visit 1 or Visit 2. The calculations assume that the dietary-precursor-independent component of EGP was identical on the two visits. No other assumption apart from tracer indistinguishability is required.

[U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]Glucose and [U-13C]glucose were used to estimate the appearance of the meal tracer (R a tracer ) on Visit 1. This amounts to using the triple-tracer approach during Visit 1 and the single-tracer approach during Visit 2. The ESM Methods describe details of the computations.

Apparent bioavailability of meal carbohydrates and [U-13C]glucose was calculated as

where M CHO and \( {M_{{\left[ {U{-^{13 }}C} \right]glucose}}} \) represent amounts of carbohydrates and [U-13C]glucose in the meal. The time to achieve 25%, 50% and 75% of cumulative glucose appearance characterised the rate of appearance of meal carbohydrates and [U-13C]glucose.

Statistical analysis

LG vs HG meals were contrasted using an unpaired t test. Visit 1 vs Visit 2 was contrasted using a paired t test. For non-normally distributed data, Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon tests were used. The incremental AUC above fasting was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. Results are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Figures show data as mean ± SEM. Analyses were conducted with the use of SPSS, versions 15 and 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The two groups of participants were comparable: LG meal: five male, age 20.8 ± 3.3 years, BMI 24.0 ± 1.5 kg/m2, HbA1c 8.7 ± 1.5%, diabetes duration 7.1 (2.9, 20.9) years, total daily insulin 0.8 ± 0.2 U kg−1 day−1; HG meal: four male, age 18.1 ± 4.0 years, BMI 22.8 ± 1.2 kg/m2, HbA1c 8.7 ± 2.0%, diabetes duration 7.4 (3.6, 11.2) years, total daily insulin 0.9 ± 0.1 U kg−1 day−1.

Plasma glucose, insulin and triacylglycerols

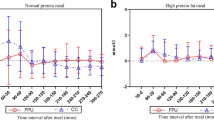

Plasma glucose, insulin and triacylglycerol profiles on Visits 1 and 2 are shown in Fig. 3 together with paired Visit 1 − Visit 2 differences. Table 1 lists fasting concentrations and incremental AUCs.

Plasma glucose, insulin infusion, plasma insulin and plasma triacylglycerol after consumption of the LG (a, c, e, g) and HG (b, d, f, h) meal. Visit 1 (meal consumption) is represented by a solid line, Visit 2 (variable-target glucose clamp) by a dashed line, and paired difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 by a grey line (n = 8, mean ± SEM)

Eating an LG meal resulted in slower and sustained elevation of plasma glucose with an unpronounced peak of 11.7 ± 2.7 mmol/l within 153 ± 104 min compared with a distinct and earlier peak of 13.8 ± 3.5 mmol/l at 98 ± 29 min after an HG meal (see ESM Table 2 for further details). During the variable-target glucose clamp, fasting and postprandial glucose levels were well reproduced. The difference between paired plasma glucose levels between the two visits was 4.1% (2.0%, 8.0%).

Fasting plasma insulin was comparable between visits and meals. Despite identical basal (0.9 ± 0.3 vs 0.9 ± 0.2 U/h; p = 0.850; LG vs HG meal) and variable (14 ± 2 and 15 ± 4 U/h; p = 0.370) insulin delivery on the two visits, there was a trend for reduced plasma insulin during Visit 1 between 45 and 120 min during studies investigating both meals (Fig. 3). Plasma insulin peaked between 65 and 70 min, and the peak was higher on Visit 1 (p = 0.036 and p = 0.017). Overall, incremental plasma insulin did not differ between the two visits (p ≥ 0.208). A marked increase was observed in incremental plasma triacylglycerol after consumption of the LG meal compared with Visit 2 (p = 0.012). This pattern was not recorded after the HG meal, as documented by comparable incremental AUCs between visits with slow decline followed by recovery at the end of the study.

Tracer concentrations and glucose turnover

Tracer concentrations on the two visits and paired differences are shown in Fig. 4. Fasting [6,6-2H2]glucose was identical on the two visits. During the LG meal study, [6,6-2H2]glucose and [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose tended to be lower on Visit 2, reflecting a trend of increased incremental glucose disposal (p = 0.050) and peak glucose disposal (p = 0.052) (Table 1, Fig. 5 and ESM Table 2). During the HG meal study, [6,6-2H2]glucose and [U-13C; 1,2,3,4,5,6,6-2H7]glucose concentrations were identical throughout, including incremental glucose disposal (p = 0.484).

Plasma tracer concentration of EGP-mimicking tracer (a, b), meal tracer (c, d) and meal-mimicking tracer (e, f) after consumption of an LG and an HG meal. Visit 1 (meal consumption) is represented by a solid line, Visit 2 (variable-target glucose clamp) by a dashed line, and paired difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 by a grey line (n = 8, mean ± SEM)

Intravenous glucose infusion (Visit 2 only), EGP (Visit 2 only) and glucose disposal after consumption of the LG meal (a, c, e) and the HG meal (b, d, f) (n = 8, mean ± SEM). In (e) and (f), Visit 1 (meal consumption) is represented by a solid line, Visit 2 (variable-target glucose clamp) by a dashed line, and paired difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 by a grey line

[U-13C]Glucose concentrations on the two visits differed considerably. This applied to both meals. On Visit 1, [U-13C]glucose concentration rose and declined more rapidly, whereas during Visit 2, lower [U-13C]glucose concentrations were observed and the dynamics were slower.

The pattern of dextrose infusion on Visit 2 differed between the two meals, whereas EGP was similar (Fig. 5). However, the trough of EGP occurred later with the HG meal (98 ± 42 vs 182 ± 62 min; p = 0.007).

Meal-attributable glucose absorption and meal tracer absorption

Apart from a similar peak absorption time of 40–45 min (p = 0.788, Table 2), the two meals presented different patterns (Fig. 6). The LG meal resulted in a sustained, slowly declining profile, which continued beyond 8 h of the observation period. The HG meal resulted in a clearly pronounced pattern with a 50% higher peak (p < 0.001). The absorption was completed within 6 h. The time to achieve 25%, 50% and 75% of cumulative glucose appearance was faster with the HG meal (p ≤ 0.003, Table 2). The LG meal resulted in at least 15% higher apparent bioavailability of dietary carbohydrates than the HG meal (p = 0.037), as glucose continued to appear beyond the duration of the experiment.

The absorption characteristics of the meal tracer were identical between the two meals (Table 2, ESM Fig. 1). In investigations of the LG meal, the meal tracer appeared about twice as rapidly as meal carbohydrates, as documented by time to peak, peak absorption rate and time to achieve 25%, 50% and 75% of cumulative glucose appearance. In investigations of the HG meal, the meal tracer appeared about 20 min faster. When normalised to carbohydrate amount, [U-13C]glucose achieved higher peak absorption than meal carbohydrates (p < 0.001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, we are the first to evaluate absorption of commonly eaten meals containing complex carbohydrates in participants with type 1 diabetes. We have documented patterns influenced by glycaemic load. After an early peak at 45 min, a sustained slowly decreasing pattern lasting in excess of 8 h was observed after an LG meal, whereas an HG meal resulted in a 50% increase in peak appearance and absorption lasting less than 6 h. At least 15% more glucose appeared systemically after the LG meal despite the carbohydrate content of the two meals being identical.

Plasma glucose levels followed the absorption patterns. After a comparable increase of 2 mmol/l over the first 30 min after the meal, plasma glucose peaked at a higher level after the HG meal at 100 min and then decreased to basal levels within 5–6 h (Fig. 3). Plasma glucose continued to increase gradually after the LG meal throughout the experiment and failed to revert to basal. This suggests that an LG evening meal results in sustained overnight elevation of glucose and increased nocturnal exposure to hyperglycaemia. Adequate management of an LG meal may require prolonged insulin delivery such as that obtained through the use of the extended bolus feature of smart insulin pumps, and a larger prandial insulin amount may be needed to compensate for the additional glucose appearing after an LG meal in accordance with heuristic observations [7].

Glycaemic load and, definitely, meal composition are the most likely main determinants of differences in absorption patterns. Although plasma glucose excursions differs after the two different meals, hyperglycaemia does not affect gastric emptying or glucose absorption in type 1 diabetes [12]. Similarly, plasma insulin does not appear to influence glucose absorption [13]. The complexity of our studies prevented investigation of the two types of meal in the same population. However, participant characteristics, including sex, age, BMI, HbA1c and diabetes duration, were very similar and thus unlikely to have affected the outcomes.

From the rate of absorption of the meal tracer ([U-13C]glucose), we infer that mixed meals containing glucose are more rapidly absorbed, achieve a higher absorption peak, and have a distinct absorption pattern not representative of meals containing complex carbohydrates. Using a meal tracer as a marker of native glucose appearance, our study suggests a 20 min deceleration of dietary complex carbohydrates compared with dietary glucose for the HG meal and a twofold deceleration for the LG meal. This deceleration explains the difference in meal tracer concentration between the two visits (Fig. 4) and confirms that dietary glucose tracers are not suitable for measuring systemic appearance of complex carbohydrates in type 1 diabetes.

Most previous studies investigated meals or drinks containing glucose and, for methodological reasons, no other simple sugars or complex carbohydrates [10–13, 25, 29, 31–35] have been looked at, with the notable exception of maize starch naturally enriched with 13C [14, 15] and intrinsically enriched starch from wheat subjected to a 13CO2-enriched atmosphere [16]. The latter investigations did not aim to achieve a constant tracer/tracee ratio, traced only one source of complex carbohydrates (maize or wheat starch), and did not use advanced computational techniques, possibly affecting the accuracy of the measurements. Our study avoided these shortcomings. Another study assessed total glucose appearance after breakfast and dinner containing complex carbohydrates in type 1 diabetes complicated by pregnancy, but EGP and gut absorption could not be differentiated [36]. In comparison with a study investigating a mixed meal containing 1.2 g glucose per kg body weight in healthy subjects [31], we observed a glucose absorption peak that was lower by 30% (HG meal) and 50% (LG meal) occurring 15–30 min later. Absorption was nearly complete within 5 h with the HG but not the LG meal.

Our approach adopts the conventional assumption of tracer indistinguishability and that the component of EGP, independently of dietary precursors, is identical on Visit 1 and Visit 2. We aimed to maintain the validity of the latter assumption by reproducing the levels of plasma glucose and plasma insulin on the two visits. By careful titration of i.v. insulin before the main study period, we achieved identical fasting conditions, including plasma glucose, plasma insulin and EGP. The variable-target glucose clamp gave identical plasma glucose levels. However, we observed higher plasma insulin on Visit 2, but this discrepancy was limited to a 75 min interval when EGP was maximally suppressed. We infer that the estimate of meal-attributable appearance is affected to a negligible extent given the large size of the meals relative to the background EGP, as exemplified by at least a tenfold difference between endogenous (∼3 μmol kg−1 min−1) and exogenous (30–60 μmol kg−1 min−1) glucose appearance during the affected period (Figs 5 and 6). Thus small inter-occasion differences in EGP have little effect on meal-attributable glucose appearance.

We dissected the measurement process into interlinked stages. Modelling of i.v. glucose tracer facilitated native glucose disposal estimation. Mass balance equations were then used to derive total glucose appearance. Physiological insights identified two components of EGP in relation to gluconeogenesis from a dietary precursor (Fig. 1). The dietary-precursor-independent EGP estimated on Visit 2 was subtracted from total glucose appearance estimated on Visit 1 to obtain meal-attributable glucose appearance. Differences in glucose disposal between the two visits were irrelevant, as glucose disposal on Visit 2 was not fed into the calculation process and was a byproduct of the study design. The contribution of the dietary-precursor component of EGP may explain, at least in part, the higher meal-attributable appearance by 20 g after the LG meal, which is richer in fat and proteins.

Methodological difficulties related to the non-steady-state of the glucoregulatory system in postprandial conditions and the intricacies of the computational problem (small measurement errors propagate into large estimation errors of glucose fluxes) [20] can be mitigated by minimising the change over time in the tracer/tracee ratio [37] in combination with the two-compartment model of glucose kinetics [26]. An advanced stochastic computational approach was found to be effective for obtaining accurate measurements [29, 30] and was adopted in the present investigation.

Although we aimed to minimise changes over time of the tracer/tracee ratios to avoid the model-misspecification error, some variations occurred (ESM Fig. 2). However, our unique validation approach [30] demonstrated that the advanced computational technique is accurate given its ability to reconstruct accurately the dextrose infusion on Visit 2. It follows that the computational approach accurately reconstructs total glucose appearance and EGP. The computational approach assumes smooth glucose fluxes [20], with the extent of smoothing drawn from a population distribution. This allowed sharing of information among individuals [28] and avoided the aberrations and oscillations that can be present when data are processed individually.

The strength of our study is in the assessment of commonly eaten meals containing simple and complex carbohydrates, and the use of advanced and validated computational approaches. Limitations include investigating separate populations to assess the two meals, and the assumption that EGP was similar on the two study occasions. None of the shortcomings should affect the main study findings.

Our results can be used to explore, in silico [38], alternative insulin-dosing strategies, including closed-loop systems [17], before use in experiential and clinical settings. The results provide novel insights into glucose turnover suitable for incorporation into advanced mathematical models of glucose regulation [39].

We conclude that large evening meals containing complex carbohydrates provide different challenges to the management of type 1 diabetes depending on the meal composition. An HG meal results in a pronounced, but shorter, absorption pattern, whereas an LG meal results in sustained and prolonged absorption and higher overall glucose appearance.

Abbreviations

- EGP:

-

Endogenous glucose production

- HG meal:

-

High-glycaemic-load meal

- LG meal:

-

Low-glycaemic-load meal

References

Laurenzi A, Bolla AM, Panigoni G et al (2011) Effects of carbohydrate counting on glucose control and quality of life over 24 weeks in adult patients with type 1 diabetes on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: a randomized, prospective clinical trial (GIOCAR). Diabetes Care 34:823–827

Zisser H, Robinson L, Bevier W et al (2008) Bolus calculator: a review of four "smart" insulin pumps. Diabetes Technol Ther 10:441–444

Heinemann L, Heise T, Wahl LC et al (1996) Prandial glycaemia after a carbohydrate-rich meal in type I diabetic patients: using the rapid acting insulin analogue [Lys(B28), Pro(B29)] human insulin. Diabet Med 13:625–629

Strachan MW, Frier BM (1998) Optimal time of administration of insulin lispro. Importance of meal composition. Diabetes Care 21:26–31

McAulay V, Ferguson SC, Frier BM (2004) Post-prandial administration of insulin lispro with a high fat meal minimizes risk of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 21:953–954

Chase HP, Saib SZ, Mackenzie T, Hansen MM, Garg SK (2002) Post-prandial glucose excursions following four methods of bolus insulin administration in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 19:317–321

Pankowska E, Blazik M, Groele L (2012) Does the fat-protein meal increase postprandial glucose level in type 1 diabetes patients on insulin pump: the conclusion of a randomized study. Diabetes Technol Ther 14:16–22

Borg R, Kuenen JC, Carstensen B et al (2010) Associations between features of glucose exposure and A1C: the A1C-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) study. Diabetes 59:1585–1590

Wolfe RR (1992) Radioactive and stable isotope tracers in biomedicine: principle and practice of kinetic analysis. Wiley-Liss, New York

Pehling G, Tessari P, Gerich JE, Haymond MW, Service FJ, Rizza RA (1984) Abnormal meal carbohydrate disposition in insulin-dependent diabetes. Relative contributions of endogenous glucose production and initial splanchnic uptake and effect of intensive insulin therapy. J Clin Invest 74:985–991

Benn JJ, Bozzard SJ, Kelley D et al (1989) Persistent abnormalities of the metabolism of an oral glucose load in insulin-treated type 1 diabetics. Metabolism 38:1047–1055

Woerle HJ, Albrecht M, Linke R et al (2008) Impaired hyperglycemia-induced delay in gastric emptying in patients with type 1 diabetes deficient for islet amyloid polypeptide. Diabetes Care 31:2325–2331

Pennant ME, Bluck LJ, Marcovecchio LM, Salgin B, Hovorka R, Dunger DB (2008) Insulin administration and rate of glucose appearance in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 31:2183–2187

Wachters-Hagedoorn RE, Priebe MG, Heimweg JA et al (2007) Low-dose acarbose does not delay digestion of starch but reduces its bioavailability. Diabet Med 24:600–606

Wachters-Hagedoorn RE, Priebe MG, Heimweg JA et al (2006) The rate of intestinal glucose absorption is correlated with plasma glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide concentrations in healthy men. J Nutr 136:1511–1516

Priebe MG, Wachters-Hagedoorn RE, Heimweg JA et al (2008) An explorative study of in vivo digestive starch characteristics and postprandial glucose kinetics of wholemeal wheat bread. Eur J Nutr 47:417–423

Hovorka R (2011) Closed-loop insulin delivery: from bench to clinical practice. Nat Rev Endocrinol 7:385–395

Wilinska ME, Chassin LJ, Schaller HC, Schaupp L, Pieber TR, Hovorka R (2005) Insulin kinetics in type-1 diabetes: continuous and bolus delivery of rapid acting insulin. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 52:3–12

ShojaeeMoradie F, Jackson NC, Jones RH, Mallet AI, Hovorka R, Umpleby AM (1996) Quantitative measurement of 3-O-methyl-D-glucose by gas chromatography mass spectrometry as a measure of glucose transport in vivo. J Mass Spectrom 31:961–966

Hovorka R, Jayatillake H, Rogatsky E, Tomuta V, Hovorka T, Stein DT (2007) Calculating glucose fluxes during meal tolerance test: a new computational approach. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293:E610–E619

Hovorka R, Shojaee-Moradie F, Carroll PV et al (2002) Partitioning glucose distribution/transport, disposal, and endogenous production during IVGTT. Am J Physiol 282:E992–E1007

Rosenblatt J, Chinkes D, Wolfe M, Wolfe RR (1992) Stable isotope tracer analysis by GC-MS, including quantification of isotopomer effects. Am J Physiol 263:E584–E596

Kalderon B, Korman SH, Gutman A, Ladipot A (1989) Glucose recycling and production in glycogenosis type I and III: stable isotope technique study. Am J Physiol 257:E346–E353

Katz J, Lee W-NP, Wals PA, Bergner EA (1989) Studies of glycogen synthesis and the Krebs cycle by mass isotopomer analysis with [U-13C]glucose rats. J Biol Chem 264:12994–13001

Basu R, Di Camillo B, Toffolo G et al (2003) Use of a novel triple-tracer approach to assess postprandial glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E55–E69

Mari A (1992) Estimation of the rate of appearance in the non-steady state with a two-compartment model. Am J Physiol 263:E400–E415

Radziuk J, McDonald TJ, Rubenstein D, Dupre J (1978) Initial splanchnic extraction of ingested glucose in normal man. Metabolism 27:657–669

Spiegelhalter D, Thomas A (1998) Graphical modeling for complex stochastic systems: the BUGS project. IEEE Intelligent Systems Their Applications 13:14–15

Haidar A, Potocka E, Boulet B, Umpleby AM, Hovorka R (2012) Estimating postprandial glucose fluxes using hierarchical Bayes modelling. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 108:102–112

Haidar A, Elleri D, Allen JM et al (2012) Validity of triple- and dual-tracer techniques to estimate glucose appearance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302:E1493–E1501

Basu R, Dalla Man C, Campioni M et al (2006) Effects of age and sex on postprandial glucose metabolism: differences in glucose turnover, insulin secretion, insulin action, and hepatic insulin extraction. Diabetes 55:2001–2014

Woerle HJ, Szoke E, Meyer C et al (2006) Mechanisms for abnormal postprandial glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290:E67–E77

Livesey G, Wilson PD, Dainty JR et al (1998) Simultaneous time-varying systemic appearance of oral and hepatic glucose in adults monitored with stable isotopes. Am J Physiol 275:E717–E728

Singhal P, Caumo A, Carey PE, Cobelli C, Taylor R (2002) Regulation of endogenous glucose production after a mixed meal in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol 283:E275–E283

Toffolo G, Dalla MC, Cobelli C, Sunehag AL (2008) Glucose fluxes during OGTT in adolescents assessed by a stable isotope triple tracer method. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 21:31–45

Murphy HR, Elleri D, Allen JM et al (2012) Pathophysiology of postprandial hyperglycaemia in women with type 1 diabetes during pregnancy. Diabetologia 55:282–293

Cobelli C, Mari A, Ferrannini E (1987) Non-steady state: error analysis of Steele's model and developments for glucose kinetics. Am J Physiol 252:E679–E689

Wilinska ME, Chassin LJ, Acerini CL, Allen JM, Dunger DB, Hovorka R (2010) Simulation environment to evaluate closed-loop insulin delivery systems in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 4:132–144

Hovorka R, Canonico V, Chassin LJ et al (2004) Non-linear model predictive control of glucose concentration in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Physiol Meas 25:905–920

Acknowledgements

A. Watts, Department of Paediatrics, University of Cambridge, provided laboratory support. D. Mundt and J. Weston, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, provided dietary support. The Diabetes Research Network Laboratory Wales (S. Luzio) measured plasma insulin. T. Hovorka, Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge, developed and validated tracer/tracee ratio calculations. We acknowledge support by the staff at the Addenbrooke’s Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility. We are grateful to study volunteers for their participation.

Funding

This work was supported by JDRF (no. 22-2006-1113, no. 22-2007-1801, no. 22-2009-801, no. 22-2009-802), Diabetes UK (BDA07/0003549), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R01DK085621), European Community Framework Programme 7 (FP7-SME-2010-1 grant number 262007), Medical Research Council Centre for Obesity and Related metabolic Diseases, National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

RH is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RH, DE, DBD, CLA and MLE co-designed the studies. JMA and DE were responsible for patient screening and enrolment and informed consent. DE, JMA, KK, LL and JH provided patient care, contributed to acquisition of data, and contributed to biochemical analysis. NJ and AMU carried out GCMS analysis. DE, AH, MEW and MN carried out or supported the data analysis including the statistical analyses. RH and DE contributed to the interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. JMA, JH, KK, MN, LL, CLA, AH, MEW, NJ, AMU, MLE and DBD critically revised the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM text

(PDF 94 kb)

ESM Table 1

(PDF 7 kb)

ESM Table 2

(PDF 48 kb)

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 43 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

(PDF 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elleri, D., Allen, J.M., Harris, J. et al. Absorption patterns of meals containing complex carbohydrates in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 56, 1108–1117 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2852-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2852-x