Abstract

Aim/hypothesis

IL-6 induces insulin resistance by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and upregulating the transcription of its target gene SOCS3. Here we examined whether the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)β/δ agonist GW501516 prevented activation of the IL-6–STAT3–suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) pathway and insulin resistance in human hepatic HepG2 cells.

Methods

Studies were conducted with human HepG2 cells and livers from mice null for Pparβ/δ (also known as Ppard) and wild-type mice.

Results

GW501516 prevented IL-6-dependent reduction in insulin-stimulated v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homologue 1 (AKT) phosphorylation and in IRS-1 and IRS-2 protein levels. In addition, treatment with this drug abolished IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation of Tyr705 and Ser727 and prevented the increase in SOCS3 caused by this cytokine. Moreover, GW501516 prevented IL-6-dependent induction of extracellular-related kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), a serine–threonine protein kinase involved in serine STAT3 phosphorylation; the livers of Pparβ/δ-null mice showed increased Tyr705- and Ser727-STAT3 as well as phospho-ERK1/2 levels. Furthermore, drug treatment prevented the IL-6-dependent reduction in phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a kinase reported to inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation on Tyr705. In agreement with the recovery in phospho-AMPK levels observed following GW501516 treatment, this drug increased the AMP/ATP ratio and decreased the ATP/ADP ratio.

Conclusions/interpretation

Overall, our findings show that the PPARβ/δ activator GW501516 prevents IL-6-induced STAT3 activation by inhibiting ERK1/2 phosphorylation and preventing the reduction in phospho-AMPK levels. These effects of GW501516 may contribute to the prevention of cytokine-induced insulin resistance in hepatic cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus are closely associated with low-grade chronic inflammation characterised by abnormal production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α [1], IL-1β [2] and IL-6 [3, 4]. Of these cytokines, IL-6 shows a strong association with obesity in both rodent and human models. Depletion of IL-6 improves insulin action in a mouse model of obesity [5], whereas in humans, elevated plasma IL-6 levels correlate positively with obesity and insulin resistance and predict the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus [6–8]. In addition, administration of IL-6 to healthy individuals induces a rise in blood glucose [9]. In vitro, IL-6 has been shown to induce insulin resistance in hepatic cells [10, 11]. Although the contribution of IL-6 to the development of insulin resistance in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle is still being debated, it is generally accepted that, at least in liver, IL-6 causes insulin resistance [12, 13].

IL-6 signals through a transmembrane receptor complex containing the common signal transducing receptor glycoprotein GP130, which activates Janus tyrosine kinases (JAK1, JAK2, TYK2), with subsequent Tyr705 phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [14]. Phosphorylated STAT3 dimerises and translocates to the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of target genes through binding to specific DNA-responsive elements [15]. In addition to activation by Tyr705 phosphorylation, STAT3 also requires phosphorylation at Ser727 to achieve maximal transcriptional activity [16, 17]. Protein kinases involved in STAT3 serine phosphorylation include protein kinase C, Jun N-terminal kinase, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [18].

The mechanism by which IL-6 induces insulin resistance in liver involves the activation of STAT3 and subsequent induction of suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) [5, 19, 20], a negative regulator of cytokine signalling [21]. Several cytokines and hormones associated with insulin resistance induce the production of SOCS proteins, which inhibit insulin signalling through several distinct mechanisms, including directly interfering with insulin receptor activation, blocking IRS activation and inducing IRS degradation [22]. In liver, overexpression of Socs3 causes insulin resistance, whereas antisense suppression of Socs3 in obese diabetic mice (db/db) ameliorates insulin resistance [23].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-inducible transcription factors that form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) and bind to consensus DNA sites [24]. In addition, PPARs may suppress inflammation through diverse mechanisms, such as reducing release of inflammatory factors or stabilisation of repressive complexes at inflammatory gene promoters [25]. Of the three PPAR isotypes found in mammals, PPARα (also known as NR1C1) and PPARγ (NR1C3) [26] are the targets for hypolipidaemic (fibrates) and glucose-lowering (thiazolidinediones) drugs, respectively. Finally, activation of the third isotype, PPARβ/δ (NR1C2) enhances fatty acid catabolism in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle and, therefore, this isotype has been proposed as a potential treatment for insulin resistance [27]. Recently, it was reported that agonist-activated PPARβ/δ interferes with IL-6-mediated acute phase reaction in the liver by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of STAT3 [28], although the exact molecular mechanism involved remains unknown. Of note, a recent study demonstrated that AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates IL-6 signalling in HepG2 cells by inhibiting STAT3 [29] and it has also been shown that the PPARβ/δ activator GW501516 can increase the activity of AMPK [30].

Given the prominent role of the STAT3–SOCS3 pathway in IL-6-mediated insulin resistance in hepatocytes, we explored whether PPARβ/δ activation by GW501516 prevents IL-6-mediated insulin resistance in human hepatic cells and the mechanisms involved. PPARβ/δ activation by GW501516 prevented IL-6-mediated induction of SOCS3 mRNA levels and STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 and Ser727 in HepG2 cells. Consistent with the role of PPARβ/δ in blocking IL-6-induced STAT3 activity, STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 and Ser727 was higher in liver from Pparβ/δ-null mice than in wild-type mice. In agreement with the inhibition of the STAT3–SOCS3 pathway caused by GW501516, this drug prevented the reduction in insulin-stimulated v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homologue 1 (AKT) phosphorylation and in IRS-1 and IRS-2 protein levels. GW501516 prevented the increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation caused by IL-6 exposure, suggesting that this mechanism contributes to its effects on STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727. Our findings also show that GW501516 prevents the reduction in phospho-AMPK levels observed in IL-6-exposed cells by increasing the AMP/ATP ratio. This mechanism could explain the reduction in STAT3 phosphorylation on Tyr705 observed following GW501516 treatment. Overall, on the basis of our findings, we suggest that PPARβ/δ activation can ameliorate insulin resistance in hepatic cells by preventing IL-6-induced activation of the STAT3–SOCS3 pathway through ERK1/2 inhibition and by restoring phospho-AMPK levels.

Methods

Materials

The PPARβ/δ ligand GW501516 was obtained from Biomol Research Labs (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Other chemicals were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

The HepG2 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in DMEM (Lonza, Barcelona, Spain) with 4.5 g/l glucose and l-glutamine, supplemented with 10% (vol./vol.) FBS (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA), penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen) and non-essential amino acids. Cell density was adjusted to 2 × 105 cells/ml and 1 ml of the cell suspension was added per well to 12 well cell culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). HepG2 cells were then incubated with 10 μmol/l GW501516 and IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for the times indicated. After incubation, RNA and total and nuclear proteins were extracted as described below. Inhibitors were added 30 min prior to incubation with IL-6.

Animals

The generation of Pparβ/δ-null mice was as described previously [31]. Six male Pparβ/δ-null mice and six of their control male wild-type mice were used. In agreement with the guidelines specified by the veterinary office of Lausanne (Switzerland), the mice were housed under standard light–dark cycle (12 h light/dark cycle) and temperature (21 ± 1°C) conditions, and fed with Provimi Kliba (Kaiseraugst, Switzerland) 3436 chow. Mice were killed at 5 to 6 months of age in accordance with the principles and guidelines established by the University of Lausanne. Liver tissue was rapidly removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Measurements of mRNA

Levels of mRNA were assessed by RT-PCR as previously described [32]. Total RNA was isolated using the Ultraspec reagent (Biotecx, Houston, TX, USA). The total RNA isolated by this method is non-degraded and free of protein and DNA contamination. The sequences of the sense and antisense primers used for amplification were: Socs3 5′-TTTTCGCTGCAGAGTGACCCC-3′ and 5′-TGGAGGAGAGAGGTCGGCTCA-3′; and 18S 5′-ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGTG-3′ and 5′-GCGCAGTGTGGTCCACTCTCA-3′. Amplification of each gene yielded a single band of the expected size (Socs3: 250 bp and 18S: 333 bp). Preliminary experiments were carried out with various amounts of cDNA to determine non-saturating conditions for PCR amplification for all the genes studied. Then, under these conditions, relative quantification of mRNA was assessed by the RT-PCR method described previously [33]. Radioactive bands were quantified by video-densitometric scanning (Vilbert Lourmat Imaging, Marne-la-Vallée, France). The results for the expression of specific mRNAs are always presented relative to the expression of the control gene (18S).

Isolation of nuclear extracts

Nuclear extracts were isolated as previously described [34]. Cells were scraped into 1.5 ml cold phosphate-buffered saline, pelleted for 10 s and re-suspended in 400 μl of cold buffer A (10 mmol/l HEPES pH 7.9 at 4°C, 1.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 10 mmol/l KCl, 0.5 mmol/l dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2 mmol/l phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] and 5 μg/ml aprotinin) by flicking the tube. Cells were allowed to swell on ice for 10 min, and tubes were then vortexed for 10 s. Samples were centrifuged for 10 s and the supernatant fraction was discarded. Pellets were re-suspended in 50 μl cold buffer C (20 mmol/l HEPES-KOH pH 7.9 at 4°C, 25% glycerol [wt/vol.], 420 mmol/l NaCl, 1.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/l EDTA, 0.5 mmol/l DTT, 0.2 mmol/l PMSF, 5 μg/ml aprotinin and 2 μg/ml leupeptin) and incubated on ice for 20 min for high-salt extraction. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 2 min at 4°C and the supernatant fraction (containing DNA-binding proteins) was stored at −80°C. Nuclear extract concentration was determined by the Bradford method.

Antibodies and immunoblotting

Antibodies against total and phospho-AMPK(Thr172), total and phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705 and Ser727) were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibody against total STAT3 was purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

To obtain total protein, cells and livers were homogenised in RIPA buffer (Sigma) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (0.2 mmol/l PMSF, 1 mmol/l sodium orthovanadate, 5.4 μg/ml aprotinin). The homogenate was centrifuged at 16,700 g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method.

Proteins from whole-cell lysates and nuclear extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, then transferred to immobilon polyvinylidene diflouride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and blotted with various antibodies (as specified in ‘Results’). Detection was achieved using the EZ-ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The size of detected proteins was estimated using protein molecular mass standards (Invitrogen).

HPLC measurement of ATP, ADP and AMP

Adenine nucleotides were separated by HPLC using an X-Bridge column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a 3.5 μm outer diameter (100 × 4.6 cm). Elution was performed with 0.1 mmol/l potassium dihydrogen phosphate, pH 6, containing 4 mmol/l tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate and 15% (vol./vol.) methanol. The conditions were as follows: 20 μl sample injection, column at room temperature, flow rate of 0.6 ml/min and UV monitoring at 260 nm.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SD of five separate experiments. Significant differences were established by one-way ANOVA, using the GraphPad InStat program (GraphPad Software V2.03) (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). When significant variations were found, the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test was applied. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

PPARβ/δ activation prevents the reduction in insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation and IRS degradation caused by IL-6

It has been previously reported that IL-6 induces insulin resistance in human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells [10;11], a frequently used in vitro system for studying the effects of insulin on hepatic cells. Cells exposed to IL-6 stimulation significantly dampened their response to insulin, as measured by AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, when cells were pre-incubated with IL-6 in the presence of 10 μmol/l GW501516, a selective ligand for PPARβ/δ with a 1000-fold higher affinity toward PPARβ/δ than PPARα and PPARγ [35], the inhibitory effect of this cytokine on insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation was prevented. Drug treatment in the absence of insulin did not affect the phosphorylation status of AKT (data not shown).

PPARβ/δ activation antagonises IL-6 action and protects against its effects on insulin signalling. HepG2 cells were stimulated with 100 nmol/l insulin for 3 min, with or without pretreatment with either 10 μmol/l GW501516 for 18 h or 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 10 min. Cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for phospho-AKT (Ser473) and total AKT (a), IRS-1 (b, c) and IRS-2 (b, d). Values are means ± SD of five independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs control cells without insulin stimulation; ††† p < 0.001 vs control cells stimulated with insulin. CT, control; INS, insulin

In addition, as IL-6-induced insulin resistance in hepatic cells has been attributed to SOCS3 [11] and this protein inhibits insulin signalling by proteasomal-mediated degradation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 [36], we also examined their protein levels. As shown in Fig. 1b, IRS-1 and IRS-2 protein levels were reduced following IL-6 exposure, but these effects were abolished in the presence of GW501516. Thus, GW501516 treatment offered protection against the effects of IL-6 on insulin signalling.

PPARβ/δ activation inhibits IL-6-induced SOCS3 expression in HepG2 cells

We then examined the effect of PPARβ/δ activation on the mRNA levels of the STAT3-target gene SOCS3. HepG2 cells exposed to IL-6 showed increased SOCS3 mRNA levels (2.7-fold induction, p < 0.01), whereas in cells co-incubated with IL-6 plus GW501516, this induction was abolished (p < 0.001 vs IL-6-stimulated cells; Fig. 2a). Dimerisation, nuclear translocation and increase in transcriptional activity of STAT3 require its phosphorylation on Tyr705. In agreement with this, IL-6 exposure increased STAT3 phosphorylation on Tyr705, and GW501516 treatment reduced STAT3 phosphorylation on Tyr705 (Fig. 2b). In addition, STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727 is required for its maximal activation [16;17]. As expected, IL-6 stimulation enhanced STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727, whereas it was prevented in the presence of GW501516 (Fig. 2b). As IL-6 activates ERK1/2 [37], which has been reported to be a kinase for STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727 [18], and we have previously reported that GW501516 prevents IL-6-induced ERK1/2 activation in adipocytes [38], we evaluated the effect of this PPARβ/δ agonist on the activation of this kinase. IL-6 exposure increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas in the presence of GW501516, phospho-ERK1/2 levels were strongly suppressed (Fig. 3a). To confirm that in our conditions IL-6-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was involved in STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727, we took advantage of U0126, a potent and specific ERK1/2 inhibitor, which binds to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–ERK 1/2, (MEK1/2), thereby inhibiting its catalytic activity as well as phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Similarly to GW501516, U0126 prevented IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727 (Fig. 3b). In addition, U0126 prevented the increase in SOCS3 mRNA levels caused by IL-6 (Fig. 3c). These findings confirm that IL-6-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation contributes to STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727, leading to increased expression of its target gene SOCS3.

The PPARβ/δ agonist GW501516 prevents IL-6-induced SOCS3 expression and STAT3 phosphorylation in HepG2 cells. a Analysis of the mRNA levels of SOCS3 in human hepatic cells untreated or treated with 10 μmol/l GW501516 for 18 h prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and analysed by RT-PCR. A representative autoradiogram and the quantification normalised to 18S mRNA levels are shown. Data are the means ± SD of five independent experiments. b Total cell (Tyr705-STAT3; b, c) or nuclear (Ser727-STAT3; b, d) extracts were subjected to western blot analysis with phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705 and Ser727) or total STAT3 antibodies. HepG2 cells were untreated or treated with 10 μmol/l GW501516 for 18 h prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for either 10 min (Ser727-STAT3) or 2.5 h (Tyr705-STAT3). Bars are the means ± SD of five independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs control; ††† p < 0.001 vs IL-6-stimulated cells. AU, arbitrary units; CT, control

PPARβ/δ activation inhibits IL-6-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. HepG2 cells were pretreated with or without 10 μmol/l U0126 or 10 μmol/l GW501516 prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 2.5 h. Cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (a) or phospho-STAT3 (Ser727) (b). c Analysis of the mRNA levels of SOCS3 in HepG2 cells untreated or treated with 10 μmol/l GW501516 for 18 h prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and analysed by RT-PCR. A representative autoradiogram and the quantification normalised to 18S mRNA levels are shown. Data are the means ± SD of five independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs control; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01 and ††† p < 0.001 vs IL-6-stimulated cells. AU, arbitrary units; CT, control

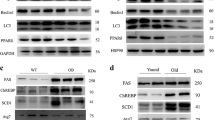

Increased levels of phospho-STAT3 (Ser727) and phospho-ERK1/2 in the liver of the Pparβ/δ-null mouse

To clearly demonstrate the involvement of PPARδ in the regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation we used the Pparβ/δ-null mouse. Livers of these mice showed a significant increase in STAT3 Ser727 and Tyr705 phosphorylation compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4a). In agreement with this, the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 was increased in Pparβ/δ-null mice (Fig. 4b). These findings demonstrate that PPARβ/δ regulates ERK1/2 and STAT3 phosphorylation in vivo.

The Pparβ/δ-null mouse shows enhanced STAT3 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in liver. Cellular extracts from wild-type or Pparβ/δ-null mouse liver were analysed by western blot with phospho-STAT3 (Ser727 and Tyr705) (a) and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (b) antibodies, as indicated. Bars are the means ± SD of five independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 vs wild-type animals. KO, Pparβ/δ-null; WT, wild-type

Pparβ/δ activation inhibits IL-6-induced AMPK downregulation in HepG2 cells

The involvement of ERK1/2 inhibition in the effects of GW501516 does not provide an explanation for the reduction of Tyr705-STAT3 phosphorylation following treatment with this PPARβ/δ activator. Therefore, we explored the effects of IL-6 and GW501516 on AMPK; activation of this kinase prevents IL-6-induced STAT3 activation in HepG2 cells by inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation on Tyr705 [29], suggesting that this kinase is a potential pharmacological target for inhibition of the deleterious effects of IL-6 in liver cells. AMPK can be activated by several kinases and by allosteric binding of AMP to the regulatory γ subunit [39]. Interestingly, it has been reported that GW501516 increases the AMP/ATP ratio both in vitro [30] and in vivo [40]. Thus, we first examined the effects of IL-6 and its co-incubation with GW501516 on AMPK phosphorylation.

IL-6 stimulation reduced phospho-AMPK levels compared with control cells, but this reduction was blocked by the presence of GW501516 (Fig. 5a). Next we measured adenine nucleotide concentrations by HPLC in HepG2 cells to determine the cellular ATP/ADP and AMP/ATP ratios. Cells exposed to IL-6 did not show significant changes. In contrast, GW501516 significantly increased the AMP/ATP ratio (Fig. 5b) and decreased the ATP/ADP ratio (Fig. 5c). Finally, as inhibitory crosstalk between AMPK and ERK1/2 has been reported [41] and AMPK inhibition increases ERK1/2 phosphorylation in liver [42], we evaluated whether AMPK activation by GW501516 contributed to the reduction in ERK1/2 phosphorylation by using the AMPK inhibitor compound C. As shown in Fig. 5d, in the presence of compound C the inhibitory effect of GW501516 on ERK1/2 phosphorylation was partially reversed, suggesting that, at least in part, AMPK activation by this drug contributes to its effects on ERK1/2.

The PPARβ/δ agonist GW501516 prevents the reduction in phospho-AMPK protein levels caused by IL-6. a Analysis of phospho-AMPK(Thr172) and total AMPK by immunoblotting of total protein extracts from HepG2 cells pretreated with or without 10 μmol/l GW501516 prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 2.5 h. AMP/ATP (b) and ATP/ADP (c) ratios in HepG2 cells pretreated with or without 10 μmol/l GW501516 prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 2.5 h. d Analysis of phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK1/2 by immunoblotting of total protein extracts from HepG2 cells pretreated with or without 10 μmol/l GW501516 prior to stimulation with 20 ng/ml IL-6 for 2.5 h in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/l compound C. Bars are the means ± SD of five independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs control; †† p < 0.01 and ††† p < 0.001 vs IL-6-stimulated cells; ‡ p < 0.05 vs IL-6 plus GW501516-stimulated cells. cC, compound C; CT, control

Discussion

Chronic production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which is associated with obesity in both human and rodent models, is considered a major link between obesity and insulin resistance [43]. In contrast to adipose-derived TNF-α, which may act locally in autocrine and paracrine manners, adipose-derived IL-6 can enter the circulation and play a systemic role in modulating insulin actions [44]. IL-6 acts primarily by activating STAT3 and upregulating the transcription of its target gene SOCS3, which causes insulin resistance by interfering with insulin receptors and/or IRS-1 [45]. Our findings demonstrate that GW501516 confers protection against the effects of IL-6 on insulin signalling in hepatic cells, as demonstrated by its effects on insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation and on IRS-1 and IRS-2 protein levels. These effects of GW501516 are consistent with the capacity of this drug to prevent IL-6-induced SOCS3 expression in HepG2 cells, suggesting that drug treatment prevents IL-6-induced STAT3 activation. Activation of STAT3 depends on its phosphorylation status and, in fact, GW501516 prevented the increase induced by IL-6 in STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 and on Ser727 phosphorylation. The effect of GW501516 on Tyr705 and Ser727 phosphorylation seems to depend on PPARβ/δ as in the livers of Pparβ/δ-null mice we observed an increase in the phosphorylation levels of Tyr705- and Ser727-STAT3.

Several kinases can phosphorylate STAT3 at Ser727, including ERK1/2 [18]. In agreement with a role for ERK1/2 in STAT3-Ser727 phosphorylation following IL-6 stimulation, we report that this cytokine increased phospho-ERK1/2 levels and that the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 reduced the levels of Ser727-STAT3 phosphorylation in IL-6-exposed cells. In addition, this inhibitor prevented the increase in SOCS3 mRNA levels caused by IL-6, suggesting that ERK1/2 inhibition is sufficient to prevent the activation of the STAT3–SOCS3 pathway. Interestingly, GW501516 completely abolished the increase in phospho-ERK1/2 levels caused by IL-6, suggesting that inhibition of this kinase was responsible for the reduction in Ser727-STAT3 phosphorylation in cells co-incubated with IL-6 plus GW501516. In agreement with the inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation on Ser727, the reduction in ERK1/2 phosphorylation caused by GW501516 treatment also seems to be PPARβ/δ-dependent, as the livers of Pparβ/δ-null mice showed increased phospho-protein levels of this kinase. Although in a previous study performed in adipocytes we observed that GW501516 reduced the interaction between STAT3 and heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) [38], which is required for STAT3 activation, in HepG2 we did not observe significant changes in the association between these two proteins (data not shown), suggesting that this mechanism does not play an important role in this cell type.

The findings of this study provide an additional mechanism by which GW501516 can inhibit IL-6-mediated activation of STAT3 in human liver cells. This mechanism involves AMPK, a kinase reported to regulate IL-6 signalling in HepG2 cells by inhibiting STAT3 [29]. The authors of this study showed that AMPK agonists reduce the IL-6-stimulated expression of inflammatory markers and SOCS3 in HepG2 cells by preventing STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705. These data are consistent with reports showing that activation of AMPK is an attractive strategy for the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [46], and suggest that downregulation of AMPK would promote the STAT3–SOCS3 pathway contributing to insulin resistance. However, when Nerstedt et al. [29] studied the effects of IL-6 on phospho-AMPK, no changes were observed. In contrast, here we report that cells exposed to IL-6 showed a reduction in AMPK phosphorylation. The discrepancy between these studies can be attributed to differences in the concentration of IL-6 used. In our study we exposed cells to 20 ng/ml IL-6 compared with the 10 ng/ml used by Nerstedt et al. [29].

In agreement with our findings, a previous study reported a reduction in AMPK and IRS-1 protein levels in heart from mice treated with IL-6 [47]. The authors of this study also reported that the potential mechanism by which IL-6 can reduce AMPK levels might involve increased protein–protein interaction between SOCS3 and AMPK, leading to ubiquitin-mediated degradation of AMPK, as reported for IRS-1 [47]. However, in our conditions we did not observe a significant reduction in the protein content of total AMPK, suggesting that additional mechanisms were involved. Of note, GW501516 treatment prevented the reduction in phospho-AMPK levels caused by IL-6 stimulation. As we observed an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio in cells incubated with GW501516, the recovery in phospho-AMPK levels induced by GW501516 could be the result of a modification of the cellular energy status. This effect of GW501516 on the AMP/ATP ratio has previously been reported in human skeletal muscle cells [30] and in liver [40], and it has been considered the result of a specific inhibition of one or more complexes of the respiratory chain, an effect of the ATP synthase system, or mitochondrial uncoupling [30]. These changes would reduce the yield of ATP synthesis by the mitochondria, leading to AMPK activation. Interestingly, as inhibitory crosstalk between ERK1/2 and AMPK has been reported [41], the activation of AMPK by GW501516 can also contribute to the reduction in phospho-ERK1/2 levels. In fact, our findings demonstrate that the effect of GW501516 on ERK1/2 phosphorylation is partially reversed in the presence of the AMPK inhibitor compound C.

In summary, on the basis of our findings, we propose that activation of PPARβ/δ prevents IL-6-induced STAT3 activation and SOCS3 upregulation, and thereby contributes to the prevention of the cytokine-mediated development of insulin resistance in hepatic cells.

Abbreviations

- AKT:

-

V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homologue 1

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ERK1/2:

-

Extracellular-related kinase 1/2

- PPAR:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SOCS3:

-

Suppressor of cytokine signalling 3

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

References

Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM (1993) Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 259:87–91

Besedovsky HO, del Rey A (1990) Metabolic and endocrine actions of interleukin-1. Effects on insulin-resistant animals. Ann NY Acad Sci 594:214–221

Bastard JP, Maachi M, van Nhieu JT et al (2002) Adipose tissue IL-6 content correlates with resistance to insulin activation of glucose uptake both in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2084–2089

Fernandez-Real JM, Vayreda M, Richart C et al (2001) Circulating interleukin 6 levels, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1154–1159

Klover PJ, Clementi AH, Mooney RA (2005) Interleukin-6 depletion selectively improves hepatic insulin action in obesity. Endocrinology 146:3417–3427

Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G (2001) Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280:E745–E751

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2001) C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 286:327–334

Vozarova B, Weyer C, Hanson K, Tataranni PA, Bogardus C, Pratley RE (2001) Circulating interleukin-6 in relation to adiposity, insulin action, and insulin secretion. Obes Res 9:414–417

Tsigos C, Papanicolaou DA, Kyrou I, Defensor R, Mitsiadis CS, Chrousos GP (1997) Dose-dependent effects of recombinant human interleukin-6 on glucose regulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:4167–4170

Senn JJ, Klover PJ, Nowak IA, Mooney RA (2002) Interleukin-6 induces cellular insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Diabetes 51:3391–3399

Kim JH, Kim JE, Liu HY, Cao W, Chen J (2008) Regulation of interleukin-6-induced hepatic insulin resistance by mammalian target of rapamycin through the STAT3-SOCS3 pathway. J Biol Chem 283:708–715

Carey AL, Febbraio MA (2004) Interleukin-6 and insulin sensitivity: friend or foe? Diabetologia 47:1135–1142

Carey AL, Bruce CR, Sacchetti M et al (2004) Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are not increased in patients with Type 2 diabetes: evidence that plasma interleukin-6 is related to fat mass and not insulin responsiveness. Diabetologia 47:1029–1037

Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F (2003) Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J 374:1–20

Bromberg J, Darnell JE Jr (2000) The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene 19:2468–2473

Zhang X, Blenis J, Li HC, Schindler C, Chen-Kiang S (1995) Requirement of serine phosphorylation for formation of STAT-promoter complexes. Science 267:1990–1994

Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE Jr (1995) Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell 82:241–250

Decker T, Kovarik P (2000) Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene 19:2628–2637

Klover PJ, Zimmers TA, Koniaris LG, Mooney RA (2003) Chronic exposure to interleukin-6 causes hepatic insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes 52:2784–2789

Senn JJ, Klover PJ, Nowak IA et al (2003) Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3), a potential mediator of interleukin-6-dependent insulin resistance in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 278:13740–13746

Krebs DL, Hilton DJ (2000) SOCS: physiological suppressors of cytokine signaling. J Cell Sci 113:2813–2819

Howard JK, Flier JS (2006) Attenuation of leptin and insulin signaling by SOCS proteins. Trends Endocrinol Metab 17:365–371

Ueki K, Kondo T, Tseng YH, Kahn CR (2004) Central role of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins in hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:10422–10427

Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP et al (2006) International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev 58:726–741

Daynes RA, Jones DC (2002) Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2:748–759

Auwerx J, Baulieu E, Beato M et al (1999) A unified nomenclature system for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell 97:161–163

Barish GD, Narkar VA, Evans RM (2006) PPAR delta: a dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 116:590–597

Kino T, Rice KC, Chrousos GP (2007) The PPARdelta agonist GW501516 suppresses interleukin-6-mediated hepatocyte acute phase reaction via STAT3 inhibition. Eur J Clin Invest 37:425–433

Nerstedt A, Johansson A, Andersson CX, Cansby E, Smith U, Mahlapuu M (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits IL-6-stimulated inflammatory response in human liver cells by suppressing phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Diabetologia 53:2406–2416

Kramer DK, Al-Khalili L, Guigas B, Leng Y, Garcia-Roves PM, Krook A (2007) Role of AMP kinase and PPARdelta in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism in human skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 282:19313–19320

Nadra K, Anghel SI, Joye E et al (2006) Differentiation of trophoblast giant cells and their metabolic functions are dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta. Mol Cell Biol 26:3266–3281

Jove M, Salla J, Planavila A et al (2004) Impaired expression of NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 and PPARgamma coactivator-1 in skeletal muscle of ZDF rats: restoration by troglitazone. J Lipid Res 45:113–123

Freeman WM, Walker SJ, Vrana KE (1999) Quantitative RT-PCR: pitfalls and potential. Biotechniques 26:112–122

Coll T, Jove M, Rodriguez-Calvo R et al (2006) Palmitate-mediated downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha in skeletal muscle cells involves MEK1/2 and nuclear factor-κB activation. Diabetes 55:2779–2787

Oliver WR Jr, Shenk JL, Snaith MR et al (2001) A selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonist promotes reverse cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:5306–5311

Rui L, Yuan M, Frantz D, Shoelson S, White MF (2002) SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J Biol Chem 277:42394–42398

Kamimura D, Ishihara K, Hirano T (2003) IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 149:1–38

Serrano-Marco L, Rodriguez-Calvo R, El Kochairi I et al (2011) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/-δ (PPAR-β/-δ) ameliorates insulin signaling and reduces SOCS3 levels by inhibiting STAT3 in interleukin-6-stimulated adipocytes. Diabetes 60:1990–1999

Scott JW, Hawley SA, Green KA et al (2004) CBS domains form energy-sensing modules whose binding of adenosine ligands is disrupted by disease mutations. J Clin Invest 113:274–284

Barroso E, Rodriguez-Calvo R, Serrano-Marco L et al (2011) The PPARβ/δ activator GW501516 prevents the down-regulation of AMPK caused by a high-fat diet in liver and amplifies the PGC-1α-lipin 1-PPARα pathway leading to increased fatty acid oxidation. Endocrinology 152:1848–1859

Du J, Guan T, Zhang H, Xia Y, Liu F, Zhang Y (2008) Inhibitory crosstalk between ERK and AMPK in the growth and proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 368:402–407

Lu DY, Tang CH, Chen YH, Wei IH (2010) Berberine suppresses neuroinflammatory responses through AMP-activated protein kinase activation in BV-2 microglia. J Cell Biochem 110:697–705

Kahn BB, Flier JS (2000) Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 106:473–481

Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A et al (1997) Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:4196–4200

Emanuelli B, Peraldi P, Filloux C, Sawka-Verhelle D, Hilton D, van Obberghen E (2000) SOCS-3 is an insulin-induced negative regulator of insulin signaling. J Biol Chem 275:15985–15991

Long YC, Zierath JR (2006) AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in metabolic regulation. J Clin Invest 116:1776–1783

Ko HJ, Zhang Z, Jung DY et al (2009) Nutrient stress activates inflammation and reduces glucose metabolism by suppressing AMP-activated protein kinase in the heart. Diabetes 58:2536–2546

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by funds from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2009-06939) and European Union ERDF funds. CIBERDEM is an Instituto de Salud Carlos III project. L. Serrano-Marco was supported by an FPI grant from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. We would like to thank the University of Barcelona’s Language Advisory Service for help.

Contribution statement

LSM, EB, IK and XP processed the samples, analysed and prepared the data and were involved in drafting the article. LM, WW and XP contributed to the interpretation of the data and revised the article. MVC designed the experiments, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serrano-Marco, L., Barroso, E., El Kochairi, I. et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) β/δ agonist GW501516 inhibits IL-6-induced signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation and insulin resistance in human liver cells. Diabetologia 55, 743–751 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2401-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2401-4