Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We systematically reviewed the impact of comorbid mental disorders on healthcare costs in persons with diabetes.

Method

We conducted a comprehensive search for studies investigating adult persons (≥18 years old) with diabetes mellitus. All studies that allowed comparison of healthcare costs between diabetic patients with mental disorders and those without were included.

Results

We identified 4,273 potentially relevant articles from a comprehensive database search. Of these, 31 primary studies (39 publications) fulfilled inclusion criteria, of which 27 examined comorbid depression. Hospitalisation rates and hospitalisation costs, frequency and costs of outpatient visits, emergency department visits, medication costs and total healthcare costs were mainly increased with small to moderate effect sizes in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders compared with diabetic patients without such problems. Frequency (standardised mean difference [SMD] = 0.35–1.26) and costs (SMD = 0.33–0.85) of mental health specialist visits were increased in the group with mental health comorbidity. Results regarding diabetes-related preventive services were inconsistent but point to a reduced utilisation rate in diabetic patients with comorbid mental disorders. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was high (I 2 range 64–98%). Pooled overall effects are therefore not reported. Studies included differ substantially regarding sample selection, assessment of diabetes and comorbid mental disorders, as well as in assessment of cost variables.

Conclusions/interpretation

In light of the increased healthcare costs and inadequate use of preventive services, comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes must become a major focus of diabetes healthcare and research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent results from the World Mental Health Surveys indicate an increased risk of mood (OR = 1.38) and anxiety disorders (OR = 1.20) in patients with diabetes compared with persons without diabetes [1]. The increased prevalence rates raise the issue of how comorbid mental disorders affect healthcare costs. Diabetes mellitus poses a complex task for the healthcare system. Patient education, routine monitoring of blood glucose and prevention of diabetes complications are just some of the common challenges in clinical practice. Mental disorders (mainly depression) in patients with diabetes were found to be associated with a significant impairment of glycaemic control [2], quality of life [3] and adherence to treatment regimen [4, 5], thus affecting management of the disease. However, data on healthcare costs in patients with diabetes with comorbid mental disorders are confusing and partly inconsistent. A national representative survey from UK, for example, revealed an association between comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes and a higher frequency of hospital admissions, more physician consultations for physical complaints and a higher rate of sick-leave days [6]. In the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey (GNHIES), by contrast, hospitalisation days were not increased in this patient group compared with diabetic patients without mental comorbidity [7]. Regarding costs of healthcare services for people with mental disorders, Simon et al. [8] found an association between depressive disorders and mental healthcare costs, whereas patients with diabetes and mental disorders from the GNHIES did not visit mental health specialists more frequently than diabetic patients without [7]. Data on diabetes-related preventive services (e.g. HbA1c determination) demonstrated slightly lower rates of receipt of preventive services in diabetic patients with mental disorders than in those without [9].

The aim of the present systematic review was to critically review and summarise the association between comorbid mental disorders and healthcare costs in patients with diabetes. The following research questions will be addressed:

-

1.

To what extent are comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes associated with increased healthcare costs in comparison to diabetic patients without mental comorbidity?

-

2.

Are there differences in this association with regard to specific comorbid mental disorders?

-

3.

Which other factors moderate the effects of comorbid mental disorders on healthcare costs?

Methods

Data collection for this study was part of the project ‘Meta-analysis of quality of life and healthcare costs in somatically ill patients with comorbid mental disorders’, which was funded by the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Inclusion criteria

Studies investigating adult patients (≥18 years old) with diabetes mellitus (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10: E10-E14) in outpatient or inpatient settings as well as persons with the aforementioned conditions from community samples were included. To increase the generalisability of results from the review, the inclusion of primary studies was not further limited to specific clinical subgroups.

All studies were included that allowed the categorisation of mental disorders or psychological burden corresponding to the following diagnostic categories: (1) mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol (ICD-10: F10; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]-IV: 303.xx, 291.xx); (2) mood disorders (ICD-10: F30-F39; DSM-IV: 292.xx, 296.xx; 300.4, 301.13, 311); (3) anxiety disorders (ICD-10: F40-F43; DSM-IV: 300.0x, 300.2x, 308.3, 309.81; (4) somatoform disorders (ICD-10: F45; DSM-IV: 300.7, 300.81); (5) eating disorders (ICD-10: F50; DSM-IV: 307.1, 307.5x); (6) disorders of adult personality and behaviour (ICD-10: F60; DSM-IV: 301.x); or (7) any mental disorder (i.e. assessment of psychiatric symptoms in general). For inclusion, primary studies had to allow comparison of healthcare costs between a group with one of the aforementioned mental disorders and a group without such comorbidities.

Primary studies were included if they assessed any healthcare cost variable either monetarily (e.g. costs of hospitalisation) or in terms of utilisation of healthcare resources (e.g. rates of hospital admissions). Healthcare costs and healthcare utilisation can be divided into direct or indirect healthcare costs. Direct costs comprise inpatient (hospital admission, length of stay), outpatient (physician visits, mental health specialist visits, emergency department visits, diabetes-related preventive services, medication costs) and other non-medical cost factors such as transport costs. Indirect costs are mainly those incurred through loss of productivity due to medical conditions.

Search strategy

The database search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PSYNDEX, EconLit and IBSS, and identified articles published until 28 December 2009 using the search structure ‘diabetes mellitus’ and ‘mental disorders’ and ‘healthcare costs / healthcare utilisation’ (the Electronic supplementary material [ESM] text contains details of the MEDLINE search strategy).

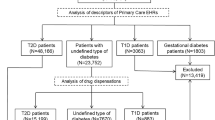

First, in a preliminary sensitive selection process, one reviewer (N. Hutter) screened titles and abstracts of English- or German-language articles relating to cost studies in diabetes mellitus (N = 4,273) (Fig. 1). Then, two reviewers (N. Hutter, A. Schnurr) independently selected relevant studies for inclusion by examining the remaining titles, abstracts or full papers (N = 502). If the two reviewers disagreed about whether to include an article, a third reviewer (H. Baumeister) was asked to review the article and disagreements were then resolved by consensus discussion. When multiple articles were published on the same study sample, the most comprehensive paper was selected as reference article. Other potentially relevant studies were retrieved by examining the reference lists of studies included (N = 184) and by identifying published articles that cited studies included (Web of Science Cited Reference Search: http://apps.isiknowledge.com/, accessed 7 January 2010) (N = 117). In addition, experts in the area were contacted and asked about published or unpublished studies that are relevant to the review.

Data abstraction

Two reviewers (N. Hutter, A. Schnurr) independently extracted data from primary studies using a data extraction form. The following information was extracted: participants (sample size, sex and age), diabetes type, mental disorders, assessment method of mental disorders (standardised diagnostic interview, self-report questionnaire, medical record or physician’s diagnosis), cut-off scores used to indicate mental disorders on self-report questionnaires, means and standard deviations of mental disorder scores, and descriptive statistics of outcomes.

To evaluate methodological characteristics of epidemiological primary studies, four indicators derived from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses [10] were assessed: (1) ascertainment of index disease (medical record, physician’s diagnosis or self-reported); (2) ascertainment of mental disorder (structured psychiatric interview, assessed with validated screening questionnaire, self-report or physician’s diagnosis); (3) comparability of the groups (study controls for age and/or sex, study controls for any additional factor); and (4) assessment of healthcare costs (medical database, patients’ self-report).

Quantitative data analysis

The data analysis was completed using Stata Statistical Software 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and Review Manager 5.0 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs using the pooled standard deviation of both groups for continuous data and OR (95% CI) for dichotomous data were computed. In studies examining more than two groups representing different grades of severity of specific mental disorders (e.g. no depression, minor depression and major depression), the groups of patients with psychiatric symptoms were merged and compared with those without psychiatric symptoms (e.g. no depression vs minor and major depression). If no measures of variability were given in study reports, exact p values as well as t or χ2 statistics were used to compute effect sizes.

Forest plots are reported (ESM Figs 1–7) for all outcomes examined in five or more primary studies. Chinn’s method for converting an OR to effect size was used to compute SMDs of continuous outcomes that had been artificially dichotomised in primary studies [11]. Studies comparing mentally comorbid patients and patients without mental disorders using β coefficients derived from regression analyses were not included in meta-analyses due to their methodological shortcomings when used as measures of effect [12].

We aimed to conduct random-effects meta-analyses for all cost outcomes with moderate heterogeneity according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (I 2 not important to moderate [0–60%]; [13]). Heterogeneity was tested for statistical significance by using Q-statistics with 95% CI. To examine the extent of heterogeneity, I 2 was computed. All random-effects meta-analyses yielded considerable heterogeneity with I 2 ranging from 64% to 98%. Hence, only study-level effect-sizes are reported.

We also aimed to explore clinical heterogeneity by conducting univariate meta-regressions for cost outcomes that had been examined in a sufficient number of primary studies (ten or more). Type of comorbid mental disorder, diabetes type, methodological criteria (assessment method of mental disorder, adjustment of covariates and assessment of outcome variable) and study size were defined a priori as potentially relevant effect-modifying variables. However, since none of the outcomes was examined in a sufficient number, meta-regressions were not conducted.

Results

The database search yielded 4,273 potentially relevant articles (Fig. 1). Of these, 31 primary studies (39 publications) [4, 6–9, 14–47] fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of primary studies

In most cases, depression was studied (n = 27) [4, 8, 9, 14–16, 18, 20, 21, 23, 25–31, 33, 34, 37, 39–42, 44–46], followed by mental disorders not further specified (n = 5) [6, 7, 9, 19, 43], anxiety disorders (n = 4) [9, 14, 18, 36] and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 3) [14, 18, 45] (ESM Table 1). Of the primary studies, 27 were based on a sample of persons with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes [4, 6–9, 14, 16, 18–21, 23, 25–30, 33, 34, 37, 40–43, 45, 46]. Four studies investigated type 2 diabetes only [15, 31, 39, 44]. Healthcare costs were examined in various facets in the studies included. Inpatient costs were assessed in terms of hospitalisation rates or hospitalisation costs (n = 15) [4, 6, 8, 15, 20, 25, 29, 31, 34, 37, 39, 42–44, 46], and length of stay (n = 9) [7, 15, 19, 20, 25, 26, 30, 42, 46]. Outpatient costs were assessed in terms of frequency and costs of outpatient visits (n = 19) [4, 6–8, 14, 15, 18–21, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31, 34, 37, 42, 45], mental health specialist visits and costs (n = 4) [4, 7, 8, 21, 36], emergency department visits (n = 11) [4, 16, 20, 21, 29, 30, 34, 37, 39, 42, 44] and medication costs (n = 6) [4, 20, 31, 34, 37, 40]. Total healthcare costs or utilisation were studied in 13 primary studies [4, 8, 9, 14, 20, 25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 37, 40, 41] and diabetes-related preventive services in five studies [7–9, 19, 23]. Indirect costs of absence from work were investigated in seven studies [6, 22, 33, 41, 42, 46, 47] (ESM Table 1). Most primary studies were conducted in the USA (n = 24). The other studies were located in Canada (n = 1), China (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), UK (n = 1), Hungary (n = 1) and Singapore (n = 1).

Direct costs

Inpatient healthcare

Increased hospitalisation rates were found in six primary studies of depressed patients with diabetes compared with diabetic patients without depression, with SMDs ranging from 0.40 to 0.68 (ESM Fig. 1) [15, 29, 31, 39, 42, 46]. One study did not find an increased hospitalisation rate in a population sample of patients with diabetes and unspecified mental health problems [6]. Two other studies reporting β coefficients derived from regression analyses did not find a significant association between depression and hospitalisation rates in patients with diabetes [25, 37]. One study reported insufficient information to compute effect sizes [44]. Another study reported a decreased hospital admission rate directly following an emergency department visit [36].

Hospitalisation costs were examined in seven studies, yielding inconsistent results. Effect sizes of four studies of patients with diabetes and depression vs those without depression ranged from SMD 0.09 to 0.20, indicating slightly increased hospitalisation costs in diabetic patients with depression [4, 8, 20, 31]. One study reporting a β coefficient found a significant association between depression and hospitalisation costs in patients with diabetes [25], whereas another study did not find a significant association [37]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute effect sizes [34].

The primary studies examining length of stay yielded inconsistent results (ESM Fig. 2). In patients with diabetes and depression, length of stay was increased in three studies compared with diabetic patients without depression (SMD 0.34–0.40) [15, 42, 46]. One study found no differences between the groups [20]. Another study reporting a β coefficient found a significant association between depression and length of stay in depressed patients with diabetes [25], whereas another study failed to find such an association [30]. Patients with diabetes and any mental health problem were found to have a slightly increased length of stay compared with those without mental comorbidity in one study [19], whereas another study of patients with diabetes and any mental health problem did not find a significant difference between the groups [7]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute an effect size [26].

Outpatient healthcare

Patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders (depression, any mental disorder and PTSD) had more outpatient visits than diabetic patients without mental comorbidity, with SMD ranging from 0.09 to 0.64 [6–8, 15, 19–21, 23, 31, 42, 45] (ESM Fig. 3). Two other studies reporting β coefficients derived from regression analyses did not find a significant association between depression and outpatient visits in depressed patients with diabetes [30, 37], whereas another study of patients with diabetes and depression found a significant association between depression and increased outpatient visits [25]. A study investigating depressive, bipolar and anxiety disorder, as well as PTSD, found significant associations (β coefficients) with decreased outpatient visits, except for depressive disorder, in patients with diabetes [18]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute an effect size [26].

Five studies investigating costs of outpatient visits showed SMDs from 0.11 to 0.43, indicating increased costs in patients with diabetes and mental disorders (depression, anxiety disorder and PTSD) compared with diabetic patients without [4, 8, 14, 20, 31] (ESM Fig. 4). One study reporting a β coefficient found a significant association between depression and outpatient costs in patients with diabetes and depression [25], whereas another study did not find a significant association [37]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute an effect size [34].

The frequency of mental health specialist visits was examined in three primary studies investigating comorbid depression and panic episodes [7, 8, 21, 36], in which effect sizes varied between 0.35 and 1.26. Patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders showed higher rates of mental health specialist visits than diabetic patients without mental comorbidity. Costs of mental health treatments were higher in patients with diabetes and depression based on two primary studies showing effect sizes of SMD 0.33 [4] and SMD 0.58 [8].

The primary studies investigating frequency of emergency department visits reported increased rates in patients with diabetes and depression compared with diabetic patients without depression (SMD 0.10–0.82) (ESM Fig. 5) [16, 20, 21, 29, 39, 42]. Two other studies reporting β coefficients derived from regression analyses did not find a significant association between depression and emergency department visits in depressed patients with diabetes [30, 37]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute an effect size [44].

Ciechanowski et al. [4] reported slightly increased emergency department costs in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders (SMD 0.17), whereas Egede et al. [20] did not find differences in costs of emergency room visits between the two groups (SMD 0.01). One other study reporting a β coefficient did not find a significant association between depression and emergency department costs in depressed patients with diabetes [37]. One study did not report sufficient information to compute an effect size [34].

Three studies reported increased costs of medications (SMD 0.40–0.48) in patients with diabetes and comorbid depression compared with diabetic patients without [4, 31, 40]. Another study reporting a β coefficient derived from regression analysis did not find a significant association between depression and medication costs in patients with diabetes and depression [37]. Two studies did not report sufficient information to compute effect sizes [20, 34].

Diabetes-related preventive services

Simon et al. [8] found a decreased rate of outpatient preventive care visits in patients with diabetes and depression compared with those without depression (SMD −0.09 [95% CI −0.16, −0.01]). The frequency of foot examinations was decreased in patients with diabetes and depression compared with those without depression (OR 0.86 [95% CI 0.81, 0.93) in one study [23], whereas two other studies of patients with diabetes and any comorbid mental health problem did not find differences between the groups (OR 0.84 [95% CI 0.40, 1.75] and OR 0.98 [0.88, 1.08]) [7, 19]. Foot sensory examinations were not associated with comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes (OR 1.06 [95% CI 1.00, 1.12]) [19], whereas rates of pedal pulse examinations were decreased (OR 0.72 [95% CI 0.68, 0.77]) [19]. Studies of receipt of eye examinations yielded inconsistent results (OR [range] 0.69–1.59) [7, 9, 19, 23, 35]. The rate of urine protein tests did not differ between patients with diabetes and any mental disorder [9] or depression [35] compared with those without mental disorders. Jones et al. [9] reported a lower rate of HbA1c determinations in patients with diabetes and mental disorders compared with diabetic patients without, whereas Desai et al. [19] found no differences. Two studies reported lower rates of HbA1c tests in patients with diabetes and comorbid depression than in those without depression (OR 0.90 [95% CI 0.84, 0.96]) and 0.61 [0.42, 0.90] respectively) [23, 35], whereas Desai et al. [19] did not find differences for patients with diabetes and any mental disorder.

Total healthcare costs

Seven studies reported increased total healthcare costs in patients with diabetes and mental disorders (depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD) compared with those without mental comorbidities (SMD [range] 0.04–0.86) (ESM Fig. 6) [4, 8, 14, 27, 28, 31, 40]. Three studies did not report sufficient information to compute effect sizes [20, 34, 37].

Indirect costs

Work absence

Absence from work was increased in patients with diabetes and depression compared with diabetic patients without depression in five primary studies (SMD [range] 0.15–0.98) [22, 41, 42, 46, 47] (ESM Fig. 7). In line with these findings, Kivimäki and colleagues [33] reported an increased HR for absence from work in patients with diabetes and depression (HR 1.98 [95% CI 1.52, 2.59]). Patients with diabetes and any mental disorder had a higher rate of absence from work than those without mental comorbidity (SMD 1.13 [95% CI 0.41, 1.85]) [6].

Discussion

The present systematic review investigated the association between comorbid mental disorders and healthcare costs based on 31 primary studies of persons with type 1 and type 2 diabetes [4, 6–9, 14–47]. The results highlight the economic impact of comorbid mental disorders in diabetes. Hospitalisation rates and costs, number and costs of outpatient visits, emergency department visits, mental health specialist visits, medication costs and total healthcare costs were shown to be increased in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders compared with diabetic patients without such disorders. The incremental healthcare costs and resource utilisation yielded small to moderate effect sizes. The question of clinical significance of these increased healthcare costs in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders should be seen in the context of the high prevalence rate [48] and the economic burden of diabetes [49]. Healthcare costs of diabetes in the USA are estimated to have exceeded $174 billion US dollars in 2007 [49]. Thus, patients with diabetes already use healthcare services to a notable degree. Against the background of this ceiling effect, a small to moderate increase of healthcare costs in the subgroup of diabetic patients with comorbid mental disorders is highly significant for healthcare professionals and policy makers. Furthermore, increased healthcare costs in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders are not limited to the healthcare system itself. The available data also emphasise the economic impact of comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes on indirect costs such as absence from work.

The present review revealed inconsistent evidence on receipt of diabetes-related preventive services in patients with diabetes and mental disorders compared with those without mental comorbidities [7–9, 19, 23, 35]. In general, the literature suggests that use of recommended diabetes-related preventive services is suboptimal in patients with diabetes, irrespective of mental comorbidity status [7, 9].

Although our review was not able to clarify the causal and temporal impact of diabetes and mental disorders on healthcare costs, the complex task and burden of managing diabetes may well contribute to psychological distress, which in turn discourages mentally distressed patients with diabetes from using adequate diabetes care. Even low levels of depressive symptoms have been shown to be associated with non-adherence to diabetes self-care [5]. As a consequence, diabetes complications occur more often in patients with diabetes and mental health comorbidity than in diabetic patients without such comorbidities [50], necessitating other costly treatments.

The additional burden of mental disorders may also lead directly to higher healthcare costs and increased resource utilisation. Patients with diabetes and mental health comorbidity need healthcare specifically focused on mental disorders. This justifiably causes higher healthcare costs in terms of some cost variables (e.g. mental healthcare provision in specialist or primary care settings). However, the finding that patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders even produce higher healthcare costs in other domains indicates that utilisation and allocation of appropriate healthcare services remain inadequate. Another explanation for these increased costs could be that patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders have a more severe somatic disease status, which in turn would result in more frequent healthcare utilisation and higher healthcare costs. This hypothesis is supported by previous findings highlighting the association between the severity of diseases and the presence of comorbid mental disorders [51–53]. However, a significant effect of mental disorders on healthcare costs was found in primary studies that had adjusted for medical comorbidities or diabetes complications [9, 14, 19, 20, 25, 26, 29–31, 34, 35, 39, 41, 42, 46, 47]. Thus, mental health comorbidities seem to be an independent predictor of healthcare costs in patients with diabetes and appear, at least partly, to explain higher healthcare costs in such patients with mental disorders.

Arguably, the finding that mental health specialist visits were increased in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders is not surprising. In a hypothetically perfect healthcare system, every patient with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders could be expected to be correctly recognised and then treated by a mental health specialist. On the other hand, persons without mental disorders would not be treated for such disorders. Accordingly, one would expect the difference in mental health specialist visits (and thus the effect size of this difference) to be infinite. Considered thus, the effect sizes found between SMD 0.35–1.26 might also be interpreted as under-use of mental healthcare services by patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders or over-use of mental healthcare services by diabetic patients without mental comorbidities. This conclusion is supported by recent reports, which have drawn attention to inadequate mental healthcare for persons with mental disorders, irrespective of comorbidities [54–56].

We aimed to conduct subgroup analyses and meta-regressions to explore clinical heterogeneity between the primary studies. Type of comorbid mental disorder, diabetes type and methodological criteria were defined a priori as potentially relevant effect-modifying variables. However, due to the small number of primary studies on the different outcomes, statistical procedures such as subgroup analyses and meta-regressions did not seem to be meaningful and were omitted in favour of a qualitative discussion of factors introducing heterogeneity.

Primary studies mainly investigated depression. Thus, the results of this review cannot be generalised to other mental disorders, as relationships to healthcare costs might differ depending on the mental health problem under study. For example, extensive worries about one’s health as a symptom of anxiety disorders could be associated with frequent use of primary care, but on the other hand might also lead to inadequate utilisation of healthcare services in other domains (e.g. emergency department visits). Moreover, serious mental disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders have been shown to be risk factors for the development and course of diabetes [57]. Healthcare utilisation patterns of patients with diabetes and serious mental disorders may differ from those of patients with diabetes and comorbid (mild to moderate) depression. Hence, future research will have to clarify the relationship of comorbid mental disorders other than depression (e.g. anxiety disorders, serious mental illness) with healthcare costs in patients with diabetes.

Furthermore, most primary studies did not differentiate healthcare costs according to type of diabetes (i.e. types 1 and 2). Yet relevant healthcare services might well differ according to diabetes type. For example, close monitoring of insulin self-management in primary or diabetes specialty care is crucial for glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes, whereas patient education regarding lifestyle changes (e.g. diet and physical activity) may play a more important role in type 2 diabetes. Hence, further studies are needed to clarify the differential effects of comorbid mental disorders on healthcare costs in patients with type 1 diabetes compared with those with type 2 diabetes.

The assessment of comorbid mental disorders was mainly based on screening instruments. When assessed through screening questionnaires, the group of patients with comorbid disorders could comprise patients with clinical disorders as well as patients with subthreshold syndromes. This association is ambiguous and further studies are therefore needed to clarify the impact of different severity grades of mental disorders on healthcare costs in patients with diabetes. The assessment of diabetes was based on either physicians’ diagnoses or patients’ self-reports. Self-reports run the risk of false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. With regard to diabetes, however, recent studies comparing patients’ self-reports with physicians’ diagnoses have reported moderate to high agreement rates, lowering the risk of misclassification bias [58–60].

With regard to the assessment of healthcare utilisation variables, most primary studies used medical records, while some relied on patient-reported data on healthcare utilisation. Patients’ self-reports might have led to bias (e.g. recall bias). However, the impact on heterogeneity between primary studies may be of minor importance, because reliability analyses of retrospective, patient-reported healthcare costs compared with cost data from administrative databases and prospective patient diaries showed moderate to high reliability [61, 62].

Finally, effects of comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes on healthcare costs could be moderated by type of healthcare system and health insurance coverage. The primary studies included were mainly conducted in the USA (n = 24). The seven other studies stem from seven different countries with different public healthcare systems. Hence, the results cannot be generalised to other than the US healthcare system, and further studies are needed to evaluate cross-cultural differences in healthcare costs of comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes.

When interpreting the results of this systematic review, the following aspects should be noted. First, feasibility considerations led us to restrict the review to English- and German-language studies. Second, the selection process of primary studies may have been biased. A preliminary selection process by one reviewer reduced the amount of 4,273 potentially relevant articles to 502 hits, which were independently examined by two reviewers. Furthermore, publication bias may have occurred and it remains unclear to what extent insignificant study results were not published. However, with our comprehensive search strategy identifying 31 primary studies, we believe that the present review constitutes a comprehensive and representative view of the topic. Third, the synthesis of the healthcare cost data was hampered by methodological heterogeneity of the primary studies included. The primary studies differ with regard to the selection of the sample (e.g. clinical or population-based samples), the assessment of the comorbid mental disorders (standardised interview, screening questionnaire, self-report), the comparability of the groups (adjustment of relevant confounding variables) and assessment of outcome (monetarily/resource utilisation). At the same time, this heterogeneity allows for a broad overview of healthcare costs in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental disorders in comparison to diabetic patients without such disorders.

Conclusion

Overall, comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes were found to be associated with increased healthcare costs. With regard to suboptimal utilisation of recommended diabetes-related preventive services, further research is needed to clarify the causal and temporal implications of comorbid mental disorders in this patient group. As yet, mainly depression has been studied, and other mental disorders should be investigated. Future studies should adjust for disease severity in order to examine mental disorders as an independent predictor of healthcare costs. The question of adequate allocation of healthcare resources tailored specifically to patients’ needs requires further attention in clinical practice and research. The diagnosis and treatment of comorbid mental disorders in patients with diabetes should be further improved in order to minimise over- or under-use of healthcare services and to assure timely receipt of preventive healthcare services. Finally, there is great need to examine results from other countries and healthcare systems other than those of the USA in order to better understand what types of delivery models are most cost efficient in managing both comorbidities.

Abbreviations

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GNHIES:

-

German National Health Interview and Examination Survey

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- SMD:

-

Standardised mean difference

References

Lin EHB, Von Korff M, on behalf of the WHO WMH Survey Consortium (2008) Mental disorders among persons with diabetes—results from the World Mental Health Surveys. J Psychosom Res 65:571–580

Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE (2000) Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 23:934–942

Baumeister H, Balke K, Härter M (2005) Psychiatric and somatic comorbidities are negatively associated with quality of life in physically ill patients. J Clin Epidemiol 58:1090–1100

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE (2000) Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 160:3278–3285

Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E et al (2007) Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care 30:2222–2227

Das-Munshi J, Stewart R, Ismail K, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R, Prince MJ (2007) Diabetes, common mental disorders, and disability: findings from the UK National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Psychosom Med 69:543–550

Hutter N, Scheidt-Nave C, Baumeister H (2009) Quality of life and health care utilization in individuals with diabetes mellitus and comorbid mental disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31:33–35

Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH et al (2005) Diabetes complications and depression as predictors of health service costs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 27:344–351

Jones LE, Clarke W, Carney CP (2004) Receipt of diabetes services by insured adults with and without claims for mental disorders. Med Care 42:1167–1175

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Available from www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm, accessed 24 July 2007

Chinn S (2000) A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med 19:3127–3131

Greenland S, Schlesselman JJ, Criqui MH (1986) The fallacy of employing standardized regression coefficients and correlations as measures of effect. Am J Epidemiol 123:203–208

Higgins JP, Green S (eds) (2009) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

Banerjea R, Sambamoorthi U, Smelson D, Pogach LM (2008) Expenditures in mental illness and substance use disorders among veteran clinic users with diabetes. J Behav Health Serv Res 35:290–303

Black SA (1999) Increased health burden associated with comorbid depression in older diabetic Mexican Americans. Results from the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly survey. Diabetes Care 22:56–64

Chou KL, Ho AH, Chi I (2005) The effect of depression on use of emergency department services in Hong Kong Chinese older adults with diabetes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20:900–902

Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W et al (2006) Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 28:9–17

Cradock-O'Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, Wang M, Lee ML (2002) Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv 53:874–878

Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB (2002) Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry 159:1584–1590

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K (2002) Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:464–470

Egede LE, Zheng D (2003) Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:104–111

Egede LE (2004) Effects of depression on work loss and disability bed days in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:1751–1753

Egede LE, Ellis C, Grubaugh A (2009) The effect of depression on self-care behaviors and quality of care in a national sample of adults with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31:422–427

Fenton JJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Ciechanowski P, Young BA (2006) Quality of preventive care for diabetes: effects of visit frequency and competing demands. Ann Fam Med 4:32–39

Finkelstein EA, Bray JW, Chen H et al (2003) Prevalence and costs of major depression among elderly claimants with diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:415–420

Fortney JC, Booth BM, Curran GM (1999) Do patients with alcohol dependence use more services? A comparative analysis with other chronic disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:127–133

Garis RI, Farmer KC (2002) Examining costs of chronic conditions in a Medicaid population. Manag Care 11:43–50

Gilmer TP, O'Connor PJ, Rush WA et al (2005) Predictors of health care costs in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:59–64

Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, Anderson GF, Cooper LA (2004) Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care 42:512–521

Husaini BA, Hull PC, Sherkat DE et al (2004) Diabetes, depression, and healthcare utilization among African Americans in primary care. J Natl Med Assoc 96:476–484

Kalsekar ID, Madhavan SM, Amonkar MM, Scott V, Douglas SM, Makela E (2006) The effect of depression on health care utilization and costs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Manag Care Interface 19:39–46

Kalsekar ID, Madhavan SM, Amonkar MM et al (2006) Impact of depression on utilization patterns of oral hypoglycemic agents in patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort analysis. Clin Ther 28:306–318

Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Hemingway H (2007) Increased sickness absence in diabetic employees: what is the role of co-morbid conditions? Diabet Med 24:1043–1048

Le TK, Able SL, Lage MJ (2006) Resource use among patients with diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, or diabetes with depression. Cost Eff Res Alloc 4:18

Lin E, Katon W, Von Korff M et al (2004) Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 27:2154–2160

Ludman E, Katon W, Russo J et al (2006) Panic episodes among patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 28:475–481

Nichols L, Barton PL, Glazner J, McCollum M (2007) Diabetes, minor depression and health care utilization and expenditures: a retrospective database study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 5:4

Niefeld MR, Braunstein JB, Wu AW, Saudek CD, Weller WE, Anderson GF (2003) Preventable hospitalization among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:1344–1349

Pawaskar MD, Anderson RT, Balkrishnan R (2007) Self-reported predictors of depressive symptomatology in an elderly population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 5:50

Rosenzweig JL, Weinger K, Poirier-Solomon L, Rushton M (2002) Use of a disease severity index for evaluation of healthcare costs and management of comorbidities of patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care 8:950–958

Stein MB, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Belik SL, Sareen J (2006) Does co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness? A population-based perspective. Psychol Med 36:587–596

Subramaniam M, Sum CF, Pek E et al (2009) Comorbid depression and increased health care utilisation in individuals with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31:220–224

Sullivan G, Han X, Moore S, Kotrla K (2006) Disparities in hospitalization for diabetes among persons with and without co-occurring mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 57:1126–1131

Sundaram M, Kavookjian J, Patrick JH, Miller LA, Madhavan SS, Scott VG (2007) Quality of life, health status and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Qual Life Res 16:165–177

Trief PM, Ouimette P, Wade M, Shanahan P, Weinstock RS (2006) Post-traumatic stress disorder and diabetes: co-morbidity and outcomes in a male veterans sample. J Behav Med 29:411–418

Vamos EP, Mucsi I, Keszei A, Kopp MS, Novak M (2009) Comorbid depression is associated with increased healthcare utilization and lost productivity in persons with diabetes: a large nationally representative Hungarian population survey. Psychosom Med 71:501–507

Von Korff M, Katon W, Lin EH et al (2005) Work disability among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1326–1332

Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H (2004) Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 27:1047–1053

American Diabetes Association (2008) Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 31:596–615

de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 63:619–630

Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K (2007) The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 29:147–155

Härter M, Baumeister H, Reuter K et al (2007) Increased 12-month prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Psychother Psychosom 76:354–360

Baumeister H, Härter M (2007) Mental disorders in patients with obesity in comparison with healthy probands. Int J Obes 31:1155–1164

Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG et al (2005) Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 352:2515–2523

Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Singleton N et al (2004) Trends in service use and treatment for mental disorders in adults throughout Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 185:378–384

Baumeister H, Härter M (2007) Prevalence of mental disorders based on general population surveys. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:537–546

Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH (2007) Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 298:1794–1796

Goldman N, Lin IF, Weinstein M, Lin YH (2003) Evaluating the quality of self-reports of hyptertension and diabetes. J Clin Epidemiol 56:148–154

Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ (2004) Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol 57:1096–1103

Baumeister H, Kriston L, Bengel J, Härter M (2010) High agreement of self-report and physician-diagnosed somatic conditions yields limited bias in examining mental-physical comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol 63:558–565

Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR (2001) Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. J Clin Epidemiol 54:136–141

Lubeck DP, Hubert HB (2005) Self-report was a viable method for obtaining health care utilization data in community-dwelling seniors. J Clin Epidemiol 58:286–290

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg, Germany for funding the research project.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 107 kb)

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 7 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

(PDF 6 kb)

ESM Fig. 3

(PDF 7 kb)

ESM Fig. 4

(PDF 7 kb)

ESM Fig. 5

(PDF 6 kb)

ESM Fig. 6

(PDF 7 kb)

ESM Fig. 7

(PDF 14 kb)

ESM 1

(PDF 38 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hutter, N., Schnurr, A. & Baumeister, H. Healthcare costs in patients with diabetes mellitus and comorbid mental disorders—a systematic review. Diabetologia 53, 2470–2479 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1873-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1873-y