Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

In addition to weight loss, bariatric surgery for severe obesity dramatically alleviates insulin resistance. In this study, we investigated whether circulating concentrations of the high-molecular-weight (HMW) form of adiponectin are increased following gastric bypass surgery. The HMW form is implicated as the multimer responsible for adiponectin’s hepatic insulin-sensitising actions.

Subjects and methods

We studied 19 women who were undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Studies were conducted prior to, and 1 and 12 months after surgery.

Results

One month after surgery, total plasma adiponectin concentrations were unchanged. Nevertheless, increases in both HMW (by 40±15%, p=0.006) and the proportion of adiponectin in the HMW form (from 40±2 to 50±2%, p<0.0001) were observed. At 12 months, total and HMW adiponectin concentrations were increased by 58±8% and 118±21%, respectively (both p<0.001). The majority (80%) of the increase of total adiponectin was due to an increase of the HMW form. After adjustment for covariates, increases of HMW and total adiponectin at 12 months were correlated with the decrease of fat mass (HMW, p=0.0076; total, p=0.0302). In subjects with improved insulin sensitivity at 12 months after surgery (n=18), the increase of HMW, but not that of total adiponectin, predicted the relative decrease of insulin resistance (HMW: p=0.0044; total: p=0.0775, after adjustment for covariates).

Conclusions/interpretation

These data suggest that the reduction of fat mass following gastric bypass surgery is an important determinant of the increase of HMW adiponectin concentrations, which in turn is associated with and may contribute to the resulting improvement of insulin sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective treatment for achieving long-term weight reduction in people with severe obesity [1–3]. In addition to marked weight loss, bariatric surgery often ameliorates or resolves obesity-related co-morbidities, particularly insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [4, 5]. The mechanisms involved in this improvement in insulin sensitivity are likely to involve the immediate reduction in food intake (accompanied by modulation of intestinal incretin hormones) [6], followed by the reduction of excess adiposity [7].

Adipose tissue produces a number of hormones, known as adipokines, that signal changes in adipose mass and energy status [8]. One of these adipokines, adiponectin, has insulin-sensitising actions in liver and skeletal muscle and anti-inflammatory/anti-atherosclerotic effects on vascular endothelium [9]. The effects of adiponectin leading to improved insulin sensitivity are mediated in part by its activation of AMP kinase, which leads to increased fatty acid oxidation and reduced ectopic triglyceride deposition in liver and muscle [8, 10]. Plasma adiponectin concentrations are reduced in obese humans [11], and decreased circulating levels are independently associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [12].

Adiponectin circulates in three major forms: as trimers (low molecular weight [LMW]), as hexamers (medium molecular weight [MMW]) and as larger multimers of 12 to 18 subunits (high molecular weight [HMW]) [13]. The production and therefore circulating levels of the different molecular-weight complexes appear to be regulated at the level of the adipocyte [14, 15]. The three major forms of adiponectin differentially activate signalling pathways in target tissues. For example, in cultured myocytes and isolated skeletal muscle, HMW and MMW, but not LMW complexes activate nuclear factor-κB, whereas the LMW form alone activates AMP kinase [16]. In cultured hepatocytes, however, AMP kinase is only activated by the larger MMW and HMW complexes [13]. HMW has been reported to be the only multimeric form of adiponectin that prevents apoptosis of cultured human endothelial cells [17]. In addition, HMW, but not MMW adiponectin effectively lowers blood glucose levels in adiponectin-deficient mice [14].

The importance of the HMW adiponectin complex in the regulation of insulin action is further supported by the observations [14] that the ratio of HMW adiponectin to total adiponectin (S A) was reduced in human subjects with type 2 diabetes and in db/db mice. Furthermore, following thiazolidinedione treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes (which increases total adiponectin levels), the increase of S A, but not the increase of total adiponectin was strongly correlated with improvements of insulin sensitivity and lowering of hepatic glucose production [14]. Similarly, a recent study reported that HMW adiponectin concentrations were better correlated than total adiponectin concentrations with a number of components of the metabolic syndrome [18].

Circulating concentrations of total adiponectin (all forms) have been shown to increase following bariatric surgery [19–22], and may be predictive of post-operative insulin sensitivity [19] and improvement of beta cell function [20]. However, the effect of weight loss surgery on the distribution of the different molecular weight adiponectin complexes has not been previously examined. Accordingly, we determined the amount and distribution of the HMW, MMW and LMW forms of circulating adiponectin in severely obese subjects undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.

Subjects and methods

Protocol

We studied 19 morbidly obese women who were undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery at the University of California, Davis Medical Center, or at Mercy San Juan Hospital in Sacramento, California. Prior to, and at 1 month and 12 months after surgery, fasting blood samples were collected and body composition was assessed at the University of California Davis General Clinical Research Center (Mather Field Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rancho Cordova, CA, USA). The Institutional Review Board of the University of California Davis approved the experimental protocol, and all subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Biochemical and anthropometric measurements

Insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco, St. Charles, MO, USA) and glucose was measured with a glucose analyser (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as previously described [23]. Non-esterified fatty acid concentrations were measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay (Waco Chemicals, Richmond, VA, USA). Adiponectin multimers were measured in duplicate by ELISA (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH, USA), a method which has recently been validated against western blot analysis [24]. In addition to measuring total adiponectin, the ELISA uses two separate protease treatments to digest either the LMW or the LMW+MMW adiponectin, enabling HMW+MMW adiponectin and HMW adiponectin alone to be measured. MMW and LMW adiponectin are then calculated by subtraction. In our laboratory, the inter-assay coefficients of variation for total, HMW+MMW, and HMW adiponectin were 9.8, 10.8, and 12.9%, respectively. Intra-assay CVs for each of the three were <6.9, <6.5, and <10%, respectively.

Body composition was determined using air-displacement plethysmography (BodPod Body composition system, Life Measurements, Concord, CA, USA). Body weight, height, waist and hip circumference were measured by a trained nurse using standard methods.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean±SEM. Univariate and bivariate statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v. 4 (San Diego, CA, USA) software. Prior to analysis, all continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Correlations between normally distributed continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation. Significant differences between levels prior to and at 1 and 12 months after surgery were assessed either by one-way repeated measures ANOVA or its non-parametric equivalent, the Friedman test. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple post-test comparisons.

Multivariate analysis was performed using the standard least squares method (JMP Start Statistics, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To assess the relationship between changes in either HMW or total adiponectin and fat mass, changes in HMW or total adiponectin were entered into the model as the response (dependent) variable, and age, initial BMI and the change in fat mass were entered as predictor (independent) variables. For the relationship between the relative change in HOMA-IR and changes in HMW or total adiponectin, the percent change in HOMA-IR was entered into the model as the response (dependent variable), and age, change in HMW or total adiponectin, as well as the change in plasma NEFA concentrations (which might also influence insulin sensitivity) were entered as predictor (independent) variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Prior to surgery

The 19 female patients studied were undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and were aged 40.6±1.8 years (mean±SEM; range 25–50), with a BMI of 45.6±1.6 kg/m2 (range 36.8–64.9). Pre-operatively, three patients had diabetes mellitus (fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l). Plasma glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, NEFA and measures of body composition prior to surgery and at 1 month and 12 months after surgery are presented in Table 1. Pre-operative adiponectin concentrations were low, as would be expected in morbidly obese subjects (total adiponectin 4.4±0.4 μg/ml [mean±SEM]; range 2.4–8.4 μg/ml). S A values averaged 40±2% (mean±SEM; range 24–54%) and were comparable with values previously reported in humans [13, 14]. Prior to surgery, no significant correlations were observed between measures of adiponectin (total adiponectin, individual multimers, or S A) and body composition (weight, BMI, fat mass, lean mass) or fasting insulin, glucose or HOMA-IR.

Results at 1 month

One month after gastric bypass surgery, BMI, body weight, fat mass and lean body mass were all decreased by 10 to 12% (Table 1). Waist circumference was also significantly reduced, as were fasting insulin concentrations and HOMA-IR, while plasma NEFA concentrations were significantly increased (all p<0.05). Fasting glucose concentrations were normalised in the three subjects with overt diabetes prior to surgery. While total plasma adiponectin concentrations were unchanged 1 month after surgery (from 4.4±0.4 to 4.5±0.3 μg/ml [mean±SEM]; p=0.78), a redistribution of adiponectin oligomers, away from the MMW and LMW forms and towards the HMW form, was already apparent (Fig. 1a). The absolute amount of HMW adiponectin was increased by 40±15% relative to pre-operative levels (from 1.8±0.2 μg/ml to 2.3±0.2 μg/ml, p=0.006). Accordingly, S A increased from 40±2% pre-operatively to 50±2% (mean±SEM; range 39–64%) at 1 month (p<0.001 vs pre-operative), and the proportion of adiponectin in the MMW form was reduced (Fig. 1b).

Changes in the absolute amounts (a) and the proportion (b) of the three adiponectin multimers from pre-operative levels (Pre) to 1 and 12 months (1, 2) after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Data are presented as means±SEM (n=19). Total adiponectin levels were increased at 12 months, and the absolute amount of high-molecular-weight (HMW) adiponectin (white bars) was increased at 1 and 12 months (from 1.8±0.2 μg/ml prior to surgery to 2.3±0.2 μg/ml at 1 month and 3.8±0.5 μg/ml at 12 months). The absolute amount of medium-molecular-weight (MMW) adiponectin (grey bars) was increased at 12 months (1.0±0.1 μg/ml vs 1.6±0.1 μg/ml), while the amount of low-molecular-weight (LMW) adiponectin (black bars) did not change significantly during the 12 months. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 relative to pre-operative levels

Results at 12 months

By 12 months, subjects had lost 32±2% of their initial weight and 50±3% of fat mass (p<0.001 relative to pre-operative levels for both). Total adiponectin concentration was increased relative to before surgery, (from 4.4±0.4 to 6.9±0.6 μg/ml, Δ=+2.5±0.3 μg/ml; p<0.001), and most of the increase (80% or 2.0 μg/ml of the total increase of 2.5 μg/ml) was due to an increase of the HMW form (Fig. 1a). The concentration of MMW adiponectin also increased, from 1.0±0.1 μg/ml before surgery to 1.6±0.2 μg/ml at 12 months (Δ=0.6±0.1 μg/ml, p<0.001), whereas LMW adiponectin concentrations were unchanged (1.5±0.1 μg/ml pre-operatively and at 12 months).

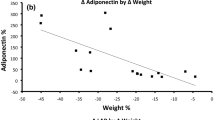

Relationships between adiponectin multimers and adiposity/body composition

The change in HMW adiponectin concentrations over the 12 months was related to changes in several measures of adiposity/body composition. At 12 months following surgery, the change in HMW adiponectin was inversely proportional to the changes in body weight (r=−0.47, p=0.022), BMI (r=−0.54, p=0.0087), waist circumference (r=−0.42, p=0.041) and fat mass (r=−0.49, p=0.017). In contrast, the change in total adiponectin concentrations was not as well correlated with changes in body weight, BMI, waist circumference and fat mass over the same period (body weight, r=−0.37, p=0.060; BMI, r=−0.41, p=0.038; waist circumference, r=−0.13, p=0.31; fat mass, r=−0.38, p=0.054).

The relationship between the change in HMW adiponectin and the change in fat mass over the 12-month period remained highly significant in a multivariate analysis (p=0.0076 after adjustment for age and initial BMI; Table 2). This model (Model 1) accounted for 49% of the variation in HMW adiponectin. Accordingly, the change in total adiponectin over this period (most of which resulted from an increase of the HMW form) was also significantly associated with the changes in fat mass, albeit less significantly (p=0.030, when adjusted for the same covariates). Analysis of the same variables at 1 month revealed no relationship between changes in total or HMW adiponectin and the changes in fat mass (data not shown). In contrast, the changes in MMW, LMW and S A were not correlated with the changes in fat mass over the 12 months post-surgery.

Adiponectin multimers and insulin resistance

We also examined the relationship between the changes in adiponectin multimers and HOMA-IR. After excluding one subject, who displayed no significant improvement (<15% decrease) in HOMA-IR (a ‘non-responder’ to use Pajvani et al.’s classification [14]), subjects with the largest increases in HMW adiponectin at 12 months post-surgery exhibited the greatest relative improvements in HOMA-IR over the same period (r=−0.43, p=0.036) (Fig. 2a). The relative decrease in HOMA-IR over the 12-month period was not significantly correlated with the changes in MMW+LMW (Fig. 2b), LMW (r=0.15, p=0.28), MMW (r=−0.07, p=0.38), or total adiponectin concentrations (r=−0.33, p=0.092) or S A (r=−0.18, p=0.23).

The change in high-molecular-weight (HMW) (a), but not in low-molecular-weight (LMW)+medium-molecular-weight (MMW) adiponectin (b) is correlated with the relative improvement of HOMA-IR following gastric bypass surgery. The change in HMW adiponectin in the 12 months post-surgery was associated with the relative improvement in HOMA-IR over the same period (r=−0.43, p=0.036 in univariate analysis; p=0.0044 after adjustment for covariates). There was no correlation between the change in LMW+MMW adiponectin concentrations and the relative improvement in HOMA-IR (r=0.06, p=0.41)

The relationship between the change in HMW adiponectin and the percent change in HOMA-IR was more pronounced after adjustment for age and the change in plasma NEFA concentrations (p=0.0044, Model 3, Table 2). When adjusted for the same covariates, the change in total adiponectin concentrations was not related to the percentage change in HOMA-IR (p=0.0775, Model 4). No significant correlations were observed between changes in total adiponectin, adiponectin multimers or S A and changes in HOMA-IR at 1 month after surgery.

Discussion

In the present study, we measured circulating levels of adiponectin oligomers before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in a group of 19 morbidly obese women. Both the absolute amount of HMW adiponectin and the proportion of adiponectin in the HMW form were increased significantly at 1 month after surgery, by which time subjects had lost ∼10% of their weight. However, total plasma adiponectin concentrations were not significantly increased at this time, as the concentrations of MMW and LMW adiponectin were reduced. At 12 months post-surgery, both total and HMW adiponectin were increased, on average, by 58±8% and 118±21%, respectively (both p<0.001), with the percentage of HMW adiponectin remaining increased (at 52±2% of total). The change in HMW adiponectin in these subjects was more closely related to the change in fat mass over the 12-month follow-up period than was the change in total plasma adiponectin concentrations, this finding being independent of age and BMI prior to surgery. In the 18 subjects with improved insulin resistance as a result of surgery, the change in HMW adiponectin, but not the change in total adiponectin or any of the other forms predicted the relative improvement in HOMA-IR.

Weight loss after gastric bypass surgery has been previously demonstrated to increase circulating total adiponectin concentrations [19–22], probably reflecting reduced adiposity, and a reduction of adipocyte size. In support of this hypothesis, we observed a strong inverse relationship (r=−0.78, p<0.002) between adipocyte volume and adiponectin secretion from isolated rat adipocytes in vitro (unpublished observation, P. J. Havel, K. L. Stanhope). While the impact of gastric bypass on adiponectin multimers has not been previously investigated, a few studies to date have examined the effects of diet-induced weight loss, with conflicting results [17, 25, 26]. The discrepancies between some of the results of other studies and the present study may reflect either the substantially lesser degree of weight loss induced by lifestyle versus surgical interventions (6–9%), or the greater severity of obesity in the subjects in the present study. Severe caloric restriction may also play a role, as one study reported increases of total and HMW adiponectin in moderately obese subjects maintained on a diet of 800 kcal/day [17].

Insulin resistance, as assessed by marked decreases in fasting insulin concentrations and HOMA-IR, was dramatically improved at both 1 and 12 months after surgery. In this study, we found that the relative change in HOMA-IR at 12 months was more closely related to the increase in HMW than to those in MMW, LMW, or total adiponectin concentrations in patients in whom insulin sensitivity was improved. This observation remained significant in multivariate analysis, and is consistent with what has been reported in insulin-resistant and diabetic subjects treated with thiazolidinediones, in that the increase in total adiponectin levels is primarily due to an increase of the HMW form [14, 26], and the increase in the proportion of HMW adiponectin is predictive of improved insulin resistance and hepatic glucose production [14].

However, in contrast to Pajvani et al. [14], we found that the absolute increase in HMW adiponectin, and not the proportion of adiponectin in the HMW form (S A) was related to increased insulin sensitivity. In this regard, our findings are more in agreement with those of Lara-Castro et al. [18], who observed that the absolute amount of HMW adiponectin was better related to differences in insulin sensitivity among humans than was S A. While it is unclear which factors could explain this discrepancy, one possible explanation is the different measurements used to assess insulin sensitivity. Pajvani et al. [14] found that the relative change in S A was better than the absolute amount of HMW adiponectin at predicting relative (%) changes in insulin sensitivity (derived from Minimal Model analysis of frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test [FSIVGTT] data) and hepatic glucose output (derived from a hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp). This result was consistent with their data in animals that HMW, but not hexameric (MMW) adiponectin dose-dependently suppressed glucose levels in adiponectin-deficient mice; and that these mice display hepatic, rather than peripheral insulin resistance [27]. In contrast, Lara-Castro et al. [18] observed that the maximally stimulated glucose disposal rate during hyperinsulinaemic clamps correlated better with the absolute amount of HMW adiponectin than with S A. Regarding insulin sensitivity, measurements from these two studies are not directly comparable with each other (or with the present study), as the maximal level of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal used in one study [18] would have completely suppressed (and precluded the measurement of) hepatic glucose output. In the present study, the use of HOMA-IR as a measure of insulin sensitivity, while convenient, does not assess dynamic changes in insulin sensitivity and glucose disposal. In non-diabetic subjects, HOMA-IR is largely a reflection of fasting insulin levels [28].

There were a few limitations to the present study. The major limitation is the small number of subjects and the fact that all subjects were women. Women typically have higher levels of total and HMW adiponectin [14], which may be due to suppression of the HMW form by testosterone [15]. A second limitation is our use of HOMA-IR, which is not the optimal method for determining insulin sensitivity/resistance, particularly in small groups of subjects. However, it was not possible to perform euglycaemic clamps or FSIVGTTs/Minimal Model analysis on the subjects in the present study.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that circulating concentrations of HMW multimeric adiponectin are increased as early as 1 month after gastric bypass surgery. Twelve months after surgery, the increase in HMW adiponectin was related to the loss of body fat, while the relative improvement in insulin sensitivity after surgery-induced weight loss was related to the increase in HMW adiponectin concentrations. These relationships were not observed at 1 month after surgery, and were considerably less significant when total adiponectin concentrations were examined. Thus, our results are consistent with the emerging view that altered adipokine secretion may contribute to the long-term alleviation of insulin resistance and diabetes following this increasingly common surgical procedure. Further studies are needed to determine whether increased production of HMW multimeric adiponectin by adipose tissue after gastric bypass surgery is a response to the marked degree of caloric restriction and/or decreased adipocyte size.

Abbreviations

- FSIVGTT:

-

frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test

- HMW:

-

high molecular weight

- HOMA-IR:

-

homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- LMW:

-

low molecular weight

- MMW:

-

medium molecular weight

- S A :

-

ratio of HMW adiponectin to total adiponectin

References

Brolin RE (2002) Bariatric surgery and long-term control of morbid obesity. Jama 288:2793–2796

Pories WJ, Albrecht RJ (2001) Etiology of type II diabetes mellitus: role of the foregut. World J Surg 25:527–531

Steinbrook R (2004) Surgery for severe obesity. N Engl J Med 350:1075–1079

Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG et al (1995) Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 222:339–350

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E et al (2004) Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 292:1724–1737

Wickremesekera K, Miller G, Naotunne TD, Knowles G, Stubbs RS (2005) Loss of insulin resistance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a time course study. Obes Surg 15:474–481

Gumbs AA, Modlin IM, Ballantyne GH (2005) Changes in insulin resistance following bariatric surgery: role of caloric restriction and weight loss. Obes Surg 15:462–473

Havel PJ (2004) Update on adipocyte hormones: regulation of energy balance and carbohydrate/lipid metabolism. Diabetes 53 (Suppl 1):S143–S151

Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T (2005) Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev 26:439–451

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y et al (2002) Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med 8:1288–1295

Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N et al (1999) Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257:79–83

Spranger J, Kroke A, Mohlig M et al (2003) Adiponectin and protection against type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lancet 361:226–228

Waki H, Yamauchi T, Kamon J et al (2003) Impaired multimerization of human adiponectin mutants associated with diabetes. Molecular structure and multimer formation of adiponectin. J Biol Chem 278:40352–40363

Pajvani UB, Hawkins M, Combs TP et al (2004) Complex distribution, not absolute amount of adiponectin, correlates with thiazolidinedione-mediated improvement in insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem 279:12152–12162

Xu A, Chan KW, Hoo RL et al (2005) Testosterone selectively reduces the high molecular weight form of adiponectin by inhibiting its secretion from adipocytes. J Biol Chem 280:18073–18080

Tsao TS, Tomas E, Murrey HE et al (2003) Role of disulfide bonds in Acrp30/adiponectin structure and signaling specificity. Different oligomers activate different signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem 278:50810–50817

Kobayashi H, Ouchi N, Kihara S et al (2004) Selective suppression of endothelial cell apoptosis by the high molecular weight form of adiponectin. Circ Res 94:e27–e31

Lara-Castro C, Luo N, Wallace P, Klein RL, Garvey WT (2006) Adiponectin multimeric complexes and the metabolic syndrome trait cluster. Diabetes 55:249–259

Faraj M, Havel PJ, Phelis S, Blank D, Sniderman AD, Cianflone K (2003) Plasma acylation-stimulating protein, adiponectin, leptin, and ghrelin before and after weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery in morbidly obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1594–1602

Guldstrand M, Ahren B, Adamson U (2003) Improved beta-cell function after standardized weight reduction in severely obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E557–E565

Holdstock C, Engstrom BE, Ohrvall M, Lind L, Sundbom M, Karlsson FA (2003) Ghrelin and adipose tissue regulatory peptides: effect of gastric bypass surgery in obese humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3177–3183

Pender C, Goldfine ID, Tanner CJ et al (2004) Muscle insulin receptor concentrations in obese patients post bariatric surgery: relationship to hyperinsulinemia. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:363–369

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Ebinuma H, Miyazaki O, Yago H, Hara K, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T (2006) A novel ELISA system for selective measurement of human adiponectin multimers by using proteases. Clin Chim Acta [Epub ahead of print]

Bobbert T, Rochlitz H, Wegewitz U et al (2005) Changes of adiponectin oligomer composition by moderate weight reduction. Diabetes 54:2712–2719

Abbasi F, Chang SA, Chu JW et al (2006) Improvements in insulin resistance with weight loss, in contrast to rosiglitazone, are not associated with changes in plasma adiponectin or adiponectin multimeric complexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290:R139–R144

Nawrocki AR, Rajala MW, Tomas E et al (2006) Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J Biol Chem 281:2654–2660

Bergman RN, Zaccaro DJ, Watanabe RM et al (2003) Minimal model-based insulin sensitivity has greater heritability and a different genetic basis than homeostasis model assessment or fasting insulin. Diabetes 52:2168–2174

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant award from the University of California Davis Health Care Systems. The University of California Davis General Clinical Research Center is supported by NIH Grant RR-019975. P. J. Havel’s laboratory receives research support from NIH Grants: HL-075675, AT-002599, AT-00293, and the American Diabetes Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Swarbrick, M.M., Austrheim-Smith, I.T., Stanhope, K.L. et al. Circulating concentrations of high-molecular-weight adiponectin are increased following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Diabetologia 49, 2552–2558 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0452-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0452-8