Background:

To determine interobserver variability in clinical target volume (CTV) of supra-diaphragmatic Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Materials and Methods:

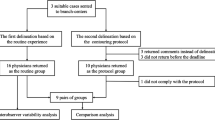

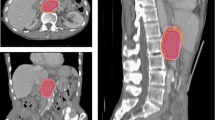

At the 2008 AIRO (Italian Society of Radiation Oncology) Meeting, the Radiation Oncology Department of Chieti proposed a multi-institutional contouring dummy-run of two cases of early stage supra-diaphragmatic Hodgkin’s lymphoma after chemotherapy. Clinical history, diagnostics, and planning CT imaging were available on Chieti’s radiotherapy website (www.radioterapia.unich.it). Participating centers were requested to delineate the CTV and submit it to the coordinating center. To quantify interobserver variability of CTV delineations, the total volume, craniocaudal, laterolateral, and anteroposterior diameters were calculated.

Results:

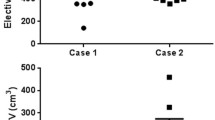

A total of 18 institutions for case A and 15 institutions for case B submitted the targets. Case A presented significant variability in total volume (range: 74.1–1,157.1 cc), craniocaudal (range: 6.5–22.5 cm; median: 16.25 cm), anteroposterior (range: 5.04–14.82 cm; median: 10.28 cm), and laterolateral diameters (range: 8.23–22.88 cm; median: 15.5 cm). Mean CTV was 464.8 cc (standard deviation: 280.5 cc). Case B presented significant variability in total volume (range: 341.8–1,662 cc), cranio-caudal (range: 8.0–28.5 cm; median: 23 cm), anteroposterior (range: 7.9–1.8 cm; median: 11.1 cm), and laterolateral diameters (range: 12.9–24.0 cm; median: 18.8 cm). Mean CTV was 926.0 cc (standard deviation: 445.7 cc).

Conclusion:

This significant variability confirms the need to apply specific guidelines to improve contouring uniformity in Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Ziel:

Diese Studie wurde durchgeführt, um die Inter-Beobachter-Variabilität des klinischen Zielvolumens bei supradiaphragmatischem Hodgkin-Lymphom festzustellen.

Methodik:

Beim 18. Treffen der AIRO (Italienischen Gesellschaft für Radioonkologie) in Mailand (November 2008) schlug die Abteilung für Strahlentherapie/Radioonkologie von Chieti eine multiinstitutionelle Zielvolumen-Konturierung („Dummy-run“) von zwei Fällen supradiaphragmatischer Hodgkin-Lymphome im frühen Stadium nach der Chemotherapie vor. Informationen über den klinischer Verlauf, die diagnostischen Befunde und die Planungs-CT-Bildgebung standen auf der Website (www.radioterapia.unich.it) der Abteilung für Strahlentherapie/Radioonkologie der Universität Chieti zur Verfügung. Die teilnehmenden Zentren wurden gebeten, die klinischen Zielvolumina zu definieren und ihre Ergebnisse bei der Koordinierungsstelle einzureichen. Um die Inter-Beobachter-Variabilität bei der Konturierung des klinischen Zielvolumens zu quantifizieren, wurden das Gesamtvolumen (cc), die kraniokaudalen, laterolateralen und die anteroposterioren Durchmesser (cm) berechnet.

Ergebnisse:

18 Zentren bezüglich des Falls A und 15 Zentren bezüglich des Falls B haben Zielvolumen-Definitionen eingereicht. Dabei wurden signifikante Variationen bei der Konturierung des klinischen Zielvolumens festgestellt. Der Range der Volumendefinition im Fall A reichte von 74,1 bis zu 1157,1 cc (Abbildung 1). Diese Variationen wurden bei der Messung der kraniokaudalen (durchschnittlich 16,25 cm; Range 6,5–22,5 cm) (Abbildung 2), anteroposterioren (durchschnittlich 10,28 cm; Range 5,04–14,82 cm) (Abbildung 3) und laterolateralen Durchmesser (durchschnittlich 15,5 cm; Range 8,23–22,88 cm) (Abbildung 4) bestätigt (Tabelle 1). Der Durchschnitt der klinischen Zielvolumina war 464,8 cc mit einer Standardabweichung von 280,5 cc. Der Range der Volumendefinition im Fall B reichte von 341,8 bis zu 1662 cc (Abbildung 1); und diese Variationen wurden bei der Messung der kraniokaudalen (durchschnittlich 23 cm; Range 8,0–28,5 cm) (Abbildung 5), anteroposterioren (durchschnittlich 11,1 cm; Range 7,9–14,8 cm) (Abbildung 6) und laterolateralen Durchmesser (durchschnittlich 18,8 cm; Range 12,9–24,0 cm) (Abbildung 7) bestätigt (Tabelle 2). Der Durchschnitt der klinischen Zielvolumina war 926,0 cc mit einer Standardabweichung von 445,7 cc.

Schlussfolgerung:

Diese signifikante Variabilität bestätigt die Notwendigkeit der Anwendung von spezifischen Guidelines, um die Uniformität der Konturierung bei Hodgkin-Lymphomen zu verbessern.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

AIRTUM working group. I Tumori in Italia. Epidemiol Prev 2009;33:1–2.

André MPE, Reman O, Fédérico M et al. First Report on the H10 EORTC/GELA/IIL Randomized Intergroup Trial on early FDG-PET scan guided treatment adaptation versus standard combined modality treatment in patients with supra-diaphragmatic Stage I/II Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, for the Groupe d’Etude Des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA), European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Lymphoma Group and the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi (IIL) [abstract]. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114:97.

Barr DR, Sherrill ET. Mean and variance of truncated normal distributions. Am Stat 1999;53:357–361.

Bollen EC, Goei R, van’t Hof-Grootenboer BE et al. Interobserver variability and accuracy of computed tomographic assessment of nodal status in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:158–162.

Bosetti C, Levi F, Ferlay J et al. The recent decline in mortality from Hodgkin Lymphomas in central and eastern Europe. Ann Oncol 2009;20:767–774.

Campbell BA, Voss N, Pickles T et al. Involved-nodal radiation therapy as a component of combination therapy for limited-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a question of field size. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5170–5174.

Cascade PN, Gross BH, Kazerooni EA et al. Variability in the detection of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in staging lung cancer: a comparison of contrast-enhanced and unenhanced CT. Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:927–931.

Chera BS, Rodriguez C, Morris CG et al. Dosimetric comparison of three different involved nodal irradiation techniques for stage II Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients: conventional radiotherapy, intensity modulated radiotherapy and three-dimensional proton radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;75:1173–1180.

Crocetti E. AIRTUM Working Group. I Tumori in Italia. Epidemiol Prev 2008;32(4).

Eich HT, Müller RP, Engenhart-Cabillic R et al. for the German Hodgkin Study Group. Involved-node radiotherapy in early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Definition and guidelines of the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG). Strahlenther Onkol 2008;184:406–410.

Engert A, Dreyling M. On behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Hodgkin’s lymphoma. ESMO Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2008;19(Suppl 2):ii65–ii66.

Engert A, Franklin J, Eich HT et al. Two cycles of Doxorubicin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, and Dacarbazine plus extended-field radiotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in early favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final results of the GHSG HD7 trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3495–3502.

Engert A, Schiller P, Josting A et al. for the German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. Involved-field radiotherapy is equally effective and less toxic compared with extended-field radiotherapy after four cycles of chemotherapy in patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the HD8 trial of the German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3601–3608.

Espeland A, Korsbrekke K, Albrektsen G et al. Observer variation in plain radiography of the lumbosacral spine. Br J Radiol 1998;71:366–375.

Favier O, Heutte N, Stamatoullas-Bastard A et al. for the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Lymphoma Group and the Groupe d’Études des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA). Survival after Hodgkin lymphoma: causes of death and excess mortality in patients treated in 8 consecutive trials. Cancer 2009;115:1680–1691.

Fletcher BD, Glicksman AS, Gieser P. Interobserver variability in the detection of cervical-thoracic Hodgkin’s disease by computed tomography. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2153–2159.

Fung WK, Tsang TS. A simulation study comparing tests for the equality of coefficients of variation. Stat Med 1998;17:2003–2014.

Girinsky T, Ghalibafian M. Radiotherapy of Hodgkin lymphoma: indications, new fields and techniques. Semin Radiat Oncol 2007;17:206–222.

Girinsky T, Specht L, Ghalibafian M et al. on behalf of the EORTC-GELA Lymphoma Group. The conundrum of Hodgkin lymphoma nodes: to be or not to be included in the involved node radiation fields. The EORTC-GELA lymphoma Group guidelines. Radiother Oncol 2008;88:202–210.

Guyatt GH, Lefeoe M, Walter S et al. Interobserver variation in the computed tomographic evaluation of mediastinal lymph node size in patients with potentially resectable lung cancer. Chest 1995;107:116–119.

Hagenbeek A, Eghbali H, Fermé C et al. for the EORTC Lymphoma Group and the Groupe d’ etudes des Lymphomes de l’ Adulte. Three cycles of MOPP/ABV M/A hybrid and involved-field irradiation is more effective than subtotal nodal irradiation (STNI) in favorable supradiaphragmatic clinical stages (CS) I–II Hodgkin’s disease (HD): preliminary results of the EORTC-GELA H8-F randomized trial in 543 patients. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, 1–5 December 2000. Blood 2000;96:575a.

Heinzelmann F, Engelhard M, Ottinger H et al. Nodal follicular lymphoma: the role of radiotherapy for stages I and II. Strahlenther Onkol 2010;186:191–196.

Heinzelmann F, Ottinger H, Engelhard M et al. Advanced-stage III/IV follicular lymphoma: treatment strategies for individual patients. Strahlenther Onkol 2010;186:247–254.

Iannitto E, Minardi V, Gobbi PG et al. Response-guided ABVD chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation therapy for intermediate-stage Hodgkin lymphoma in the pre-positron emission tomography era: a Gruppo Italiano Studio Linfomi (GISL) prospective trial. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009;9:138–144.

International Commission of Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing, Recording and Reporting Photon Beam Therapy. ICRU Report 50, ICRU, Bethesda, MD, 1993.

International Commission of Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing, Recording and Reporting Photon Beam Therapy (Supplement to ICRU Report 50). ICRU Report 62, ICRU, Bethesda, MD, 1999.

Johnson AC, Thomopoulos NT. Characteristics and tables of the left-truncated normal distribution. Annual Conference Proceedings of the Midwest Decision Sciences Institute: April 2004, Cleveland.

Kelley K. Sample size planning for the coefficient of variation from the accuracy in parameter estimation approach. Behavior Research Methods 2007;39:755–766.

Lammering G, De Ruysscher D, van Baardwijk A et al. The use of FDG-PET to target tumors by radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 2010;186:471–481.

Longo DL, Glatstein E, Duffey PL et al. Alternating MOPP and ABVD chemotherapy plus mantle-field radiation therapy in patients with massive mediastinal Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:3338–3346.

Matzinger O, Poortmans P, Giraud JY et al. for the EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Quality Assurance in the 22991 EORTC ROG trial in localized prostate cancer: dummy run and individual case review. Radiother Oncol 2009;90:285–290.

Mazonakis M, Lyraraki E, Varveris C et al. Conceptus dose from involved-field radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma on a linear accelerator equipped with MLCs. Strahlenther Onkol 2009;185:355–363.

Micheli A, Ciampichini R, Oberaigner W et al. for the EUROCARE Working Group. The advantage of women in cancer survival: an analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1017–1027.

Nogová L, Reineke T, Eich HT et al. for the GHSG. Extended field radiotherapy, combined modality treatment or involved field radiotherapy for patients with stage IA lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG). Ann Oncol 2005;16:1683–1687.

Noordijk EM, Carde P, Dupouy N et al. Combined-modality therapy for clinical stage I or II Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term results of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer H7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3128–3135.

Noordijk EM, Thomas J, Fermé C et al. First results of the EORTC-GELA H9 randomized trials: the H9-trial (comparing 3 radiation dose levels) and H9-U trial (comparing 3 chemotherapy schemes) in patients with favorable or unfavorable early stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). In ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2005. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(Suppl 1):6505.

Rasch C, Eisbruch A, Remeijer P et al. Irradiation of paranasal sinus tumors, a delineation and dose comparison study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:120–127.

Robinson PJ. Radiology’s Achilles’ heel: error in variation in the interpretation of the Roentgen image. Br J Radiol 1997;70:1085–1098.

Steenbakkers RJHM, Duppen JC, Fitton I et al. Observer variation in target volume delineation of lung cancer related to radiation oncologist-computer interaction: a ‘Big Brother’ evaluation. Radiother Oncol 2005;77:182–190.

Struikmans H, Warlam-Rodenhuis C, Stam T et al. Interobserver variability of clinical target volume delineation of glandular breast tissue and of boost volume in tangential breast irradiation. Radiother Oncol 2005;76:293–299.

Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO Classification of tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press, 2008.

Tai P, Van Dyk J, Yu E et al. Variability of target volume delineation in cervical esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;42:277–288.

Vassilakopoulos TP, Angelopoulou MK, Siakantaris MP et al. Combination chemotherapy plus low-dose involved-field radiotherapy for early clinical stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:765–781.

Verdecchia A, Guzzinati S, Francisci S et al. for the EUROCARE Working Group. Survival trends in European cancer patients diagnosed from 1988 to 1999. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1042–1066.

Villeirs GM, Van Vaerenbergh K, Vakaet L et al. Interobserver delineation variation using CT versus combined CT + MRI in intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 2005;181:424–430.

Weiss E, Hess CF. The impact of gross tumor volume (GTV) and clinical target volume (CTV) definition on the total accuracy in radiotherapy theoretical aspects and practical experiences. Strahlenther Onkol 2003;179:21–30.

Weiss E, Richter S, Krauss T et al. Conformal radiotherapy planning of cervix carcinoma: differences in the delineation of clinical target volume. A comparison between gynaecologic and radiation oncologists. Radiother Oncol 2003;67:87–95.

Weltens C, Menten J, Feron M et al. Interobservers variations in gross tumor volume delineation of brain tumors on computed tomography and impact of magnetic resonance imaging. Radiother Oncol 2001;60:49–59.

Yahalom J, Mauch P. The involved field is back: issues in delineating the radiation field in Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol 2002;13(Suppl 1):79–83.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Genovesi, ., Cèfaro, G.A., Vinciguerra, A. et al. Interobserver variability of clinical target volume delineation in supra-diaphragmatic Hodgkin’s disease. Strahlenther Onkol 187, 357–366 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-011-2221-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-011-2221-y

Key Words

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Conformal radiotherapy

- Clinical target volume delineation

- Interobserver variation

- Quality assurance