Abstract

Background

Elevated plasma homocysteine (Hcy) is considered to be a risk factor of coronary artery disease (CAD), although this is still controversially discussed. This study investigated the role of Hcy in young patients with CAD in southern China.

Methods

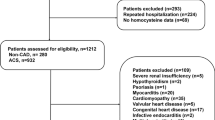

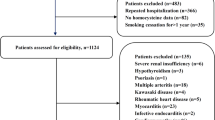

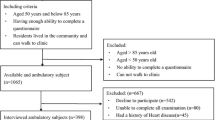

A total of 146 consecutive patients (aged ≤ 55 years) with angiographically proven CAD were enrolled in the study and 138 age-matched non-CAD individuals were included as the control group. Hcy levels were measured by enzymatic assay. Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) was defined as Hcy ≥ 15 µmol/l. A 10-year CAD risk was calculated using the Framingham risk score (FRS) modified according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III.

Results

There were significant differences between the CAD and control groups with regard to male sex (P < 0.01), smoking history (P < 0.05), and triglyceride levels (TG, P < 0.05), but no remarkable difference in other conventional risk factors (all P > 0.05). Hcy and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels were significantly higher in the CAD group than those in the control group (both P < 0.05). The FRS and estimated 10-year absolute CAD event risk were low in both groups and did not show a statistical difference. Multivariate logistic regression showed that male sex (odds ratio, OR, 3.68; 95 % confidence interval, 95 % CI, 1.54–10.01), smoking (OR, 2.54; 95 % CI, 1.15–5.36), TG (OR, 1.30; 95 % CI, 1.08–3.06), hs-CRP (OR, 3.74; 95 % CI, 1.72–12.21), and HHcy (OR, 2.03; 95 % CI, 1.26–5.83) were independently correlated with CAD in young patients.

Conclusion

HHcy is an important independent risk factor for CAD in young patients in southern China after adjusting for other risk factors.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Erhöhtes Plasmahomozystein (Hcy) gilt als Risikofaktor für koronare Herzkrankheit (KHK), ist aber immer noch umstritten. Mit der vorliegenden Studie wurde die Rolle von Hcy bei jungen Patienten mit KHK in Südchina untersucht.

Methoden

Insgesamt nahmen 146 konsekutive junge Patienten mit angiographischem KHK-Nachweis (Alter ≤ 55 Jahre) und 138 altersentsprechende Probanden ohne KHK als Kontrollgruppe an der Studie teil. Die Hcy-Werte wurden mit einem enzymatischen Assay gemessen. Eine Hyperhomozysteinämie war definiert als Hcy-Wert ≥ 15 µmol/l. Unter Einsatz des Framingham-Risikoscores (FRS) in seiner Modifikation durch das National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III wurde das 10-Jahres-KHK-Risiko berechnet.

Ergebnisse

Es gab signifikante Unterschiede bei männlichem Geschlecht (p < 0,01), Raucheranamnese (p < 0,05) und Triglyzeridspiegeln (TG), (p < 0,05), aber keine nennenswerte Differenz bei anderen konventionellen Risikofaktoren (sämtliche p > 0,05) zwischen der KHK- und der Kontrollgruppe. Die Werte für Hcy und hochsensitives C-reaktives Protein (hs-CRP) waren in der KHK-Gruppe signifikant höher als in der Kontrollgruppe (beide p < 0,05). FRS und geschätztes absolutes 10-Jahres-KHK-Risiko waren in beiden Gruppen niedrig und wiesen keine statistische Differenz auf. Die multivariate logistische Regression zeigte, dass männliches Geschlecht (Odds Ratio, OR: 3,68; 95 %-Konfidenzintervall, 95%-KI: 1,54–10,01), Rauchen (OR: 2,54; 95 %-KI: 1,15–5,36), TG (OR: 1,30; 95 %-KI: 1,08–3,06), hs-CRP (OR: 3,74; 95 %-KI: 1,72–12,21) und HHcy (OR: 2,03; 95 %-KI: 1,26–5,83) bei jungen Patienten unabhängig mit KHK korreliert waren.

Schlussfolgerung

HHcy erweist sich nach Berücksichtigung anderer Risikofaktoren als wichtiger unabhängiger Risikofaktor für Patienten mit vorzeitiger KHK in Südchina.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Huang Y, Hu Y, Mai W et al (2011) Plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein is an independent risk factor in young patients with coronary artery disease. Dis Markers 31:295–301

Eichler K, Puhan MA, Steurer J, Bachmann LM (2007) Prediction of first coronary events with the Framingham score: a systematic review. Am Heart J 153:722–731, 731.e1–8

Zarich S, Luciano C, Hulford J, Abdullah A (2006) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in young patients with acute MI: does the Framingham risk score underestimate cardiovascular risk in this population. Diab Vasc Dis Res 3:103–107

Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M et al (2009) Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease: a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 151:496–507

Kampoli AM, Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N et al (2012) Clinical utility of biomarkers in premature atherosclerosis. Curr Med Chem 19:2521–2533

Veeranna V, Zalawadiya SK, Niraj A et al (2011) Homocysteine and reclassification of cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 58:1025–1033

Clarke R, Halsey J, Bennett D, Lewington S (2011) Homocysteine and vascular disease: review of published results of the homocysteine-lowering trials. J Inherit Metab Dis 34:83–91

Holmes MV, Newcombe P, Hubacek JA et al (2011) Effect modification by population dietary folate on the association between MTHFR genotype, homocysteine, and stroke risk: a meta-analysis of genetic studies and randomised trials. Lancet 378:584–594

Clarke R, Halsey J, Lewington S et al (2010) Effects of lowering homocysteine levels with B vitamins on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause-specific mortality: meta-analysis of 8 randomized trials involving 37 485 individuals. Arch Intern Med 170:1622–1631

Cho DY, Kim KN, Kim KM et al (2012) Combination of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and homocysteine may predict an increased risk of coronary artery disease in Korean population. Chin Med J (Engl) 25:569–573

McCullough PA, Li S, Jurkovitz CT et al (2008) Chronic kidney disease, prevalence of premature cardiovascular disease, and relationship to short-term mortality. Am Heart J 156:277–283

Oudi ME, Aouni Z, Mazigh C et al (2010) Homocysteine and markers of inflammation in acute coronary syndrome. Exp Clin Cardiol 15:e25–28

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al (2003) The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 289:2560–2572

(o A) (2003) Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26(Suppl 1):S5–20

The Association Committee of Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia (2007) The 2007 guidelines for prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults in China. Chin J Cardiol (Chin) 35:390–419

Logue J, Thompson L, Romanes F et al (2010) Management of obesity: summary of SIGN guideline. BMJ 340:c154

Cui H, Wang F, Fan L et al (2011) Association factors of target organ damage: analysis of 17,682 elderly hypertensive patients in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 124:3676–3681

Talbert RL (2002) New therapeutic options in the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III. Am J Manag Care 8(12 Suppl):S301–307

Smith SC Jr (2006) Current and future directions of cardiovascular risk prediction. Am J Cardiol 97:28A–32A

Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D et al (2009) Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis: from folate fortification to the recent clinical trials. Eur Heart J 30:6–15

Banos-Gonzalez MA, Angles-Cano E, Cardoso-Saldana G et al (2012) Lipoprotein(a) and homocysteine potentiate the risk of coronary artery disease in male subjects. Circ J 76:1953–1957

Di MMN, Tremoli E, Coppola A et al (2010) Homocysteine and arterial thrombosis: challenge and opportunity. Thromb Haemost 103:942–961

Kampoli AM, Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N et al (2012) Clinical utility of biomarkers in premature atherosclerosis. Curr Med Chem 19:2521–2533

Cho DY, Kim KN, Kim KM et al (2012) Combination of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and homocysteine may predict an increased risk of coronary artery disease in Korean population. Chin Med J (Engl) 125:569–573

Nagele P, Meissner K, Francis A et al (2011) Genetic and environmental determinants of plasma total homocysteine levels: impact of population-wide folate fortification. Pharmacogenet Genomics 21:426–431

Schneider JA, Rees DC, Liu YT, Clegg JB (1998) Worldwide distribution of a common methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation. Am J Hum Genet 62:1258–1260

Chai HT, Chen YL, Chung SY et al (2011) Value and level of plasma homocysteine in patients with angina pectoris undergoing coronary angiographic study. Int Heart J 52:280–285

Perrone-Filardi P, Achenbach S, Mohlenkamp S et al (2011) Cardiac computed tomography and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy for risk stratification in asymptomatic individuals without known cardiovascular disease: a position statement of the Working Group on Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 32:1986–1993, 1993a, 1993b

Clarke R, Bennett DA, Parish S et al (2012) Homocysteine and coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of MTHFR case-control studies, avoiding publication bias. PLoS Med 9:e1001177

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by the Medical Scientific Research Grant of Health Ministry of Guangdong province, China (No: B2011310, A2012663), Scientific Research Fund of Foshan, Guangdong, China (No: 201108204, 201208210), and Scientific Research Fund of Shunde, Guangdong, China (No: 201208210). We thank Professor Lingxian Zhu and Doctor Dangdang Yu (majored in medical statistics, from Southern Medical University, China) for their great help in the statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Yanxian Wu and Yuli Huang contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Huang, Y., Hu, Y. et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia is an independent risk factor in young patients with coronary artery disease in southern China. Herz 38, 779–784 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-013-3761-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-013-3761-y