Abstract

Introduction

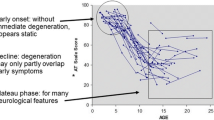

Ataxia–Telangiectasia (A-T) syndrome is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cerebellar ataxia, oculocutaneous telangiectasia, immunodeficiency, chromosome instability, radiosensitivity, and predisposition to malignancy. There is growing evidence that A–T patients suffer from pathologic inflammation that is responsible for many symptoms of this syndrome, including neurodegeneration, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, accelerated aging, and insulin resistance. In addition, epidemiological studies have shown A–T heterozygotes, somewhat like deficient patients, are susceptible to ionizing irradiation and have a higher risk of cancers and metabolic disorders.

Area covered

This review summarizes clinical and molecular findings of inflammation in A–T syndrome.

Conclusion

Ataxia–Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM), a master regulator of the DNA damage response is the protein known to be associated with A–T and has a complex nuclear and cytoplasmic role. Loss of ATM function may induce immune deregulation and systemic inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Zaki Dizaji M, Akrami SM, Abolhassani H, Rezaei N, Aghamohammadi A. Ataxia telangiectasia syndrome: moonlighting ATM. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(12):1155–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2017.1392856.

Chun HH, Gatti RA. Ataxia–telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA Repair. 2004;3(8):1187–96.

Dizaji MZ, Rezaei N, Yaghmaie M, Yaseri M, Sayedi SJ, Azizi G, et al. Phospho-SMC1 in-cell ELISA based detection of ataxia telangiectasia. Int J Pediatr Massha. 2016;4(12):3957–67. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijp.2016.7751.

Driessen GJ, Ijspeert H, Weemaes CM, Haraldsson A, Trip M, Warris A, et al. Antibody deficiency in patients with ataxia telangiectasia is caused by disturbed B- and T-cell homeostasis and reduced immune repertoire diversity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(5):1367 e9–75 e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.053.

Moin M, Aghamohammadi A, Kouhi A, Tavassoli S, Rezaei N, Ghaffari SR, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia in Iran: clinical and laboratory features of 104 patients. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37(1):21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.03.002.

Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Crawford TO, Winkelstein JA, Carson KA, Lederman HM. Immunodeficiency and infections in ataxia-telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 2004;144(4):505–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.046.

Kraus M, Lev A, Simon AJ, Levran I, Nissenkorn A, Levi YB, et al. Disturbed B and T cell homeostasis and neogenesis in patients with ataxia telangiectasia. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34(5):561–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-014-0044-1.

Ghiasy S, Parvaneh L, Azizi G, Sadri G, Zaki Dizaji M, Abolhassani H, et al. The clinical significance of complete class switching defect in ataxia telangiectasia patients. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):499–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2017.1292131.

Chopra C, Davies G, Taylor M, Anderson M, Bainbridge S, Tighe P, et al. Immune deficiency in Ataxia–Telangiectasia: a longitudinal study of 44 patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176(2):275–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.12262.

Bredemeyer AL, Huang CY, Walker LM, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. Aberrant V(D)J recombination in ataxia telangiectasia mutated-deficient lymphocytes is dependent on nonhomologous DNA end joining. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2620–5.

Lumsden JM, McCarty T, Petiniot LK, Shen R, Barlow C, Wynn TA, et al. Immunoglobulin class switch recombination is impaired in Atm-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2004;200(9):1111–21.

Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Dai S, Zhao Y, van Dijk-Hard IF, Gatti RA, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. ATM is not required in somatic hypermutation of VH, but is involved in the introduction of mutations in the switch mu region. J Immunol. 2003;170(7):3707–16.

Ammann AJ, Hong R. Autoimmune phenomena in ataxia telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 1971;78(5):821–6.

Kutukculer N, Aksu G. Is there an association between autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ataxia–telangiectasia? Autoimmunity. 2000;32(2):145–7.

Meyts I, Weemaes C, De Wolf-Peeters C, Proesmans M, Renard M, Uyttebroeck A, et al. Unusual and severe disease course in a child with ataxia–telangiectasia. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003;14(4):330–3.

Heath J, Goldman FD. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in a boy with ataxia telangiectasia on immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32(1):e25–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181bf29b6.

Sari A, Okuyaz C, Adiguzel U, Ates NA. Uncommon associations with ataxia–telangiectasia: vitiligo and optic disc drusen. Ophthalm Genet. 2009;30(1):19–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13816810802415256.

Pasini AM, Gagro A, Roic G, Vrdoljak O, Lujic L, Zutelija-Fattorini M. Ataxia telangiectasia and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatrics. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1279.

Shao L, Fujii H, Colmegna I, Oishi H, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Deficiency of the DNA repair enzyme ATM in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2009;206(6):1435–49. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20082251.

Westbrook AM, Schiestl RH. Atm-deficient mice exhibit increased sensitivity to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis characterized by elevated DNA damage and persistent immune activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(5):1875–84. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2584.

Deng X, Ljunggren-Rose A, Maas K, Sriram S. Defective. ATM-p53-mediated apoptotic pathway in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):577–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20600.

Reichenbach J, Schubert R, Schindler D, Muller K, Bohles H, Zielen S. Elevated oxidative stress in patients with ataxia telangiectasia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4(3):465–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/15230860260196254.

Barzilai A, Rotman G, Shiloh Y. ATM deficiency and oxidative stress: a new dimension of defective response to DNA damage. DNA Repair. 2002;1(1):3–25.

McKinnon PJ. ATM and ataxia telangiectasia. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(8):772–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400210.

McGrath-Morrow SA, Collaco JM, Crawford TO, Carson KA, Lefton-Greif MA, Zeitlin P, et al. Elevated serum IL-8 levels in ataxia telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):682.e1–684.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.007.

McGrath-Morrow SA, Collaco JM, Detrick B, Lederman HM. Serum Interleukin-6 levels and pulmonary function in ataxia–telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 2016;171:256–61 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.002.

Privette ED, Ram G, Treat JR, Yan AC, Heimall JR. Healing of granulomatous skin changes in ataxia–telangiectasia after treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin and topical mometasone 0.1% ointment. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(6):703–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12411.

Mitra A, Gooi J, Darling J, Newton-Bishop JA. Infliximab in the treatment of a child with cutaneous granulomas associated with ataxia telangiectasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):676–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.060.

Chiam LY, Verhagen MM, Haraldsson A, Wulffraat N, Driessen GJ, Netea MG, et al. Cutaneous granulomas in ataxia telangiectasia and other primary immunodeficiencies: reflection of inappropriate immune regulation? Dermatology. 2011;223(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000330335.

Paller AS, Massey RB, Curtis MA, Pelachyk JM, Dombrowski HC, Leickly FE, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous lesions in patients with ataxia–telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 1991;119(6):917–22.

Schroeder SA, Swift M, Sandoval C, Langston C. Interstitial lung disease in patients with ataxia–telangiectasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39(6):537–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20209.

Shoimer I, Wright N, Haber RM. Noninfectious Granulomas. A sign of an underlying immunodeficiency? J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(3):259–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1203475415626085.

Erttmann SF, Hartlova A, Sloniecka M, Raffi FA, Hosseinzadeh A, Edgren T, et al. Loss of the DNA damage repair kinase ATM impairs inflammasome-dependent anti-bacterial innate immunity. Immunity. 2016;45(1):106–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.018.

Hartlova A, Erttmann SF, Raffi FA, Schmalz AM, Resch U, Anugula S, et al. DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. Immunity. 2015;42(2):332–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.012.

Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):155–68.

Ribezzo F, Shiloh Y, Schumacher B (eds) Systemic DNA damage responses in aging and diseases. Semin Cancer Biol; 2016

Yang Y, Hui CW, Li J, Herrup K. The interaction of the atm genotype with inflammation and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85863. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085863.

Fakhoury M. Role of immunity and inflammation in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases. Neuro Degener Dis. 2015;15(2):63–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000369933.

Quarantelli M, Giardino G, Prinster A, Aloj G, Carotenuto B, Cirillo E, et al. Steroid treatment in ataxia–telangiectasia induces alterations of functional magnetic resonance imaging during prono-supination task. Eur j Paediatr Neurol. 2013;17(2):135–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.06.002.

Broccoletti T, Del Giudice E, Cirillo E, Vigliano I, Giardino G, Ginocchio VM, et al. Efficacy of very-low-dose betamethasone on neurological symptoms in ataxia–telangiectasia. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(4):564–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03203.x.

Broccoletti T, Del Giudice E, Amorosi S, Russo I, Di Bonito M, Imperati F, et al. Steroid-induced improvement of neurological signs in ataxia–telangiectasia patients. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02060.x.

Buoni S, Zannolli R, Sorrentino L, Fois A. Betamethasone and improvement of neurological symptoms in ataxia–telangiectasia. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1479–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.63.10.1479.

Zannolli R, Buoni S, Betti G, Salvucci S, Plebani A, Soresina A, et al. A randomized trial of oral betamethasone to reduce ataxia symptoms in ataxia telangiectasia. Mov Disord. 2012;27(10):1312–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25126.

Rossi L, Castro M, D’Orio F, Damonte G, Serafini S, Bigi L, et al. Low doses of dexamethasone constantly delivered by autologous erythrocytes slow the progression of lung disease in cystic fibrosis patients. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33(1):57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.04.004.

Chessa L, Leuzzi V, Plebani A, Soresina A, Micheli R, D’Agnano D, et al. Intra-erythrocyte infusion of dexamethasone reduces neurological symptoms in ataxia teleangiectasia patients: results of a phase 2 trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-5.

Leuzzi V, Micheli R, D’Agnano D, Molinaro A, Venturi T, Plebani A, et al. Positive effect of erythrocyte-delivered dexamethasone in ataxia–telangiectasia. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(3):e98. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000098.

Menotta M, Biagiotti S, Bianchi M, Chessa L, Magnani M. Dexamethasone partially rescues ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) deficiency in ataxia telangiectasia by promoting a shortened protein variant retaining kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(49):41352–63. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.344473.

Mavrou A, Tsangaris GT, Roma E, Kolialexi A. The ATM gene and ataxia telangiectasia. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(1B):401–5.

Lavin MF. Ataxia–telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(10):759–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2514.

van Os NJ, Roeleveld N, Weemaes CM, Jongmans MC, Janssens GO, Taylor AM, et al. Health risks for ataxia–telangiectasia mutated heterozygotes: a systematic review, meta-analysis and evidence-based guideline. Clin Genet. 2016;90(2):105–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12710.

Spring K, Ahangari F, Scott SP, Waring P, Purdie DM, Chen PC, et al. Mice heterozygous for mutation in Atm, the gene involved in ataxia–telangiectasia, have heightened susceptibility to cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;32(1):185–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng958.

Mercer JR, Cheng KK, Figg N, Gorenne I, Mahmoudi M, Griffin J, et al. DNA damage links mitochondrial dysfunction to atherosclerosis and the metabolic syndrome. Circ Res. 2010;107(8):1021–31. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218966.

Barlow C, Eckhaus MA, Schaffer AA, Wynshaw-Boris A. Atm haploinsufficiency results in increased sensitivity to sublethal doses of ionizing radiation in mice. Nat Genet. 1999;21(4):359–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/7684.

Worgul BV, Smilenov L, Brenner DJ, Junk A, Zhou W, Hall EJ. Atm heterozygous mice are more sensitive to radiation-induced cataracts than are their wild-type counterparts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(15):9836–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.162349699.

Connolly L, Lasarev M, Jordan R, Schwartz JL, Turker MS. Atm haploinsufficiency does not affect ionizing radiation mutagenesis in solid mouse tissues. Radiat Res. 2006;166(1 Pt 1):39–46. https://doi.org/10.1667/RR3578.1.

Mao JH, Wu D, DelRosario R, Castellanos A, Balmain A, Perez-Losada J. Atm heterozygosity does not increase tumor susceptibility to ionizing radiation alone or in a p53 heterozygous background. Oncogene. 2008;27(51):6596–600. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2008.280.

Barnes PJ. Mechanisms of development of multimorbidity in the elderly. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(3):790–806. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00229714.

Schneider JG, Finck BN, Ren J, Standley KN, Takagi M, Maclean KH, et al. ATM-dependent suppression of stress signaling reduces vascular disease in metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2006;4(5):377–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.002.

Macaulay VM, Salisbury AJ, Bohula EA, Playford MP, Smorodinsky NI, Shiloh Y. Downregulation of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor in mouse melanoma cells is associated with enhanced radiosensitivity and impaired activation of Atm kinase. Oncogene. 2001;20(30):4029–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1204565.

Ching JK, Luebbert SH, Collins RLt, Zhang Z, Marupudi N, Banerjee S, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated impacts insulin-like growth factor 1 signalling in skeletal muscle. Exp Physiol. 2013;98(2):526–35. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2012.066357.

Smirnov DA, Cheung VG. ATM gene mutations result in both recessive and dominant expression phenotypes of genes and microRNAs. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(2):243–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.003.

Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(11):1603–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006.

Mittler RROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22(1):11–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.002.

Kamsler A, Daily D, Hochman A, Stern N, Shiloh Y, Rotman G, et al. Increased oxidative stress in ataxia telangiectasia evidenced by alterations in redox state of brains from Atm-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):1849–54.

Barlow C, Dennery PA, Shigenaga MK, Smith MA, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ 2nd, et al. Loss of the ataxia–telangiectasia gene product causes oxidative damage in target organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(17):9915–9.

Campbell A, Krupp B, Bushman J, Noble M, Proschel C, Mayer-Proschel M. A novel mouse model for ataxia-telangiectasia with a N-terminal mutation displays a behavioral defect and a low incidence of lymphoma but no increased oxidative burden. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(22):6331–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv342.

Reliene R, Schiestl RH. Experimental antioxidant therapy in ataxia telangiectasia. Clin Med Oncol. 2008;2:431–6.

Reliene R, Schiestl RH. Antioxidants suppress lymphoma and increase longevity in Atm-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2007;137(1 Suppl):229S–32S.

D’Souza AD, Parish IA, Krause DS, Kaech SM, Shadel GS. Reducing mitochondrial ROS improves disease-related pathology in a mouse model of ataxia–telangiectasia. Mol Therapy. 2013;21(1):42–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2012.203.

Kim J, Wong PK. Oxidative stress is linked to ERK1/2-p16 signaling-mediated growth defect in ATM-deficient astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(21):14396–404. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M808116200.

Guo Z, Kozlov S, Lavin MF, Person MD, Paull TT. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science. 2010;330(6003):517–21. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192912.

Yeo AJ, Fantino E, Czovek D, Wainwright CE, Sly PD, Lavin MF. Loss of ATM in airway epithelial cells is associated with susceptibility to oxidative stress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(3):391–3. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201611-2210LE.

Pallardo FV, Lloret A, Lebel M, d’Ischia M, Cogger VC, Le Couteur DG, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in some oxidative stress-related genetic diseases: Ataxia–Telangiectasia, Down Syndrome, Fanconi Anaemia and Werner Syndrome. Biogerontology. 2010;11(4):401–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-010-9269-4.

Ambrose M, Goldstine JV, Gatti RA. Intrinsic mitochondrial dysfunction in ATM-deficient lymphoblastoid cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(18):2154–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddm166.

Maciejczyk M, Mikoluc B, Pietrucha B, Heropolitanska-Pliszka E, Pac M, Motkowski R, et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial abnormalities and antioxidant defense in ataxia–telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome and Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Redox Biol. 2016;11:375–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.030.

Tripathi DN, Zhang J, Jing J, Dere R, Walker CL. A new role for ATM in selective autophagy of peroxisomes (pexophagy). Autophagy. 2016;12(4):711–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2015.1123375.

Zhang J, Tripathi DN, Jing J, Alexander A, Kim J, Powell RT, et al. ATM functions at the peroxisome to induce pexophagy in response to ROS. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(10):1259–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3230.

Le Guezennec X, Brichkina A, Huang YF, Kostromina E, Han W, Bulavin DV. Wip1-dependent regulation of autophagy, obesity, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2012;16(1):68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.003.

Yan Y, Finkel T. Autophagy as a regulator of cardiovascular redox homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.003.

Shiloh Y, Tabor E, Becker Y. Abnormal response of ataxia–telangiectasia cells to agents that break the deoxyribose moiety of DNA via a targeted free radical mechanism. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4(10):1317–22.

Yi M, Rosin MP, Anderson CK. Response of fibroblast cultures from ataxia–telangiectasia patients to oxidative stress. Cancer Lett. 1990;54(1–2):43–50.

Sharma NK, Lebedeva M, Thomas T, Kovalenko OA, Stumpf JD, Shadel GS, et al. Intrinsic mitochondrial DNA repair defects in Ataxia Telangiectasia. DNA Repair. 2014;13:22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.11.002.

Stratigi K, Chatzidoukaki O, Garinis GA. DNA damage-induced inflammation and nuclear architecture. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2016.09.008.

Radoshevich L, Dussurget O. Cytosolic innate immune sensing and signaling upon infection. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:313. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00313.

Nakad R, Schumacher B. DNA damage response and immune defense: links and mechanisms. Front Genet. 2016;7:147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2016.00147.

Paludan SR, Bowie AG. Immune sensing of DNA. Immunity. 2013;38(5):870–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.004.

Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458(7237):514–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07725.

Choubey D, Panchanathan R. IFI16, an amplifier of DNA-damage response: Role in cellular senescence and aging-associated inflammatory diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;28:27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.04.002.

Mankan AK, Hornung V. Sox2 as a servant of two masters. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(4):335–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3121.

Karakasilioti I, Kamileri I, Chatzinikolaou G, Kosteas T, Vergadi E, Robinson AR, et al. DNA damage triggers a chronic autoinflammatory response, leading to fat depletion in NER progeria. Cell Metab. 2013;18(3):403–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.011.

Yu E, Calvert PA, Mercer JR, Harrison J, Baker L, Figg NL, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage can promote atherosclerosis independently of reactive oxygen species through effects on smooth muscle cells and monocytes and correlates with higher-risk plaques in humans. Circulation. 2013;128(7):702–12. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002271.

Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):222–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.1980.

van der Burgh R, Nijhuis L, Pervolaraki K, Compeer EB, Jongeneel LH, van Gijn M, et al. Defects in mitochondrial clearance predispose human monocytes to interleukin-1beta hypersecretion. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(8):5000–12. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.536920.

Martinon F. Dangerous liaisons: mitochondrial DNA meets the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity. 2012;36(3):313–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.005.

Palmai-Pallag T, Bachrati CZ. Inflammation-induced DNA damage and damage-induced inflammation: a vicious cycle. Microbes Infect. 2014;16(10):822–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2014.10.001.

Pateras IS, Havaki S, Nikitopoulou X, Vougas K, Townsend PA, Panayiotidis MI, et al. The DNA damage response and immune signaling alliance: Is it good or bad? Nature decides when and where. Pharmacol Therap. 2015;154:36–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.06.011.

Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–36.

Shimizu I, Yoshida Y, Suda M, Minamino T. DNA damage response and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2014;20(6):967–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.008.

Jackson JG, Pereira-Smith OM. p53 is preferentially recruited to the promoters of growth arrest genes p21 and GADD45 during replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8356–60. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1752.

Cao X, Li M. A new pathway for senescence regulation. Genom Proteom Bioinf. 2015;13(6):333–5.

Kang HT, Park JT, Choi K, Kim Y, Choi HJC, Jung CW, et al. Chemical screening identifies ATM as a target for alleviating senescence. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(6):616–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2342.

Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434(7035):864–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03482.

Wallace MD, Southard TL, Schimenti KJ, Schimenti JC. Role of DNA damage response pathways in preventing carcinogenesis caused by intrinsic replication stress. Oncogene. 2014;33(28):3688–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.339.

Wunderlich R, Ruehle PF, Deloch L, Unger K, Hess J, Zitzelsberger H, et al. Interconnection between DNA damage, senescence, inflammation, and cancer. Front Biosci. 2017;22:348–69.

Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133(6):1019–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039.

Acosta JC, O’Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133(6):1006–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038.

Liu D, Hornsby PJ. Senescent human fibroblasts increase the early growth of xenograft tumors via matrix metalloproteinase secretion. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3117–26. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3452.

Hui CW, Herrup K. Individual cytokines modulate the neurological symptoms of ATM deficiency in a region specific Manner(1,2,3). eNeuro. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0032-15.2015.

Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, Iannitto ML, Ricciardi MR, Di Gialleonardo V, et al. ATM-ATR-dependent up-regulation of DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated with a senescent phenotype. Blood. 2009;113(15):3503–11. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-08-173914.

Miyamoto S. Nuclear initiated NF-kappaB signaling: NEMO and ATM take center stage. Cell Res. 2011;21(1):116–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2010.179.

Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436(7054):1186–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03884.

Weil S, Memmer S, Lechner A, Huppert V, Giannattasio A, Becker T, et al. Natural Killer group 2D ligand depletion reconstitutes natural killer cell immunosurveillance of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2017;8:387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00387.

Wiemann K, Mittrucker HW, Feger U, Welte SA, Yokoyama WM, Spies T, et al. Systemic NKG2D down-regulation impairs NK and CD8 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175(2):720–9.

Molfetta R, Quatrini L, Zitti B, Capuano C, Galandrini R, Santoni A, et al. Regulation of NKG2D expression and signaling by endocytosis. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(11):790–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2016.08.015.

Exley AR, Buckenham S, Hodges E, Hallam R, Byrd P, Last J, et al. Premature ageing of the immune system underlies immunodeficiency in ataxia telangiectasia. Clin Immunol. 2011;140(1):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2011.03.007.

Gatei M, Shkedy D, Khanna KK, Uziel T, Shiloh Y, Pandita TK, et al. Ataxia–telangiectasia: chronic activation of damage-responsive functions is reduced by alpha-lipoic acid. Oncogene. 2001;20(3):289–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1204111.

Rashi-Elkeles S, Elkon R, Weizman N, Linhart C, Amariglio N, Sternberg G, et al. Parallel induction of ATM-dependent pro- and antiapoptotic signals in response to ionizing radiation in murine lymphoid tissue. Oncogene. 2006;25(10):1584–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1209189.

Stern N, Hochman A, Zemach N, Weizman N, Hammel I, Shiloh Y, et al. Accumulation of DNA damage and reduced levels of nicotine adenine dinucleotide in the brains of Atm-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(1):602–8. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M106798200.

Shiloh Y, Lederman HM. Ataxia–telangiectasia (A–T): an emerging dimension of premature ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;33:76–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.002.

Lasry A, Ben-Neriah Y. Senescence-associated inflammatory responses: aging and cancer perspectives. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):217–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2015.02.009.

Metcalfe JA, Parkhill J, Campbell L, Stacey M, Biggs P, Byrd PJ, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in ataxia telangiectasia. Nat Genet. 1996;13(3):350–3.

Smilenov LB, Morgan SE, Mellado W, Sawant SG, Kastan MB, Pandita TK. Influence of ATM function on telomere metabolism. Oncogene. 1997;15(22):2659–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1201449.

Xia SJ, Shammas MA, Shmookler Reis RJ. Reduced telomere length in ataxia–telangiectasia fibroblasts. Mutat Res. 1996;364(1):1–11.

Naka K, Tachibana A, Ikeda K, Motoyama N. Stress-induced premature senescence in hTERT-expressing ataxia telangiectasia fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(3):2030–7. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M309457200.

Wood LD, Halvorsen TL, Dhar S, Baur JA, Pandita RK, Wright WE, et al. Characterization of ataxia telangiectasia fibroblasts with extended life-span through telomerase expression. Oncogene. 2001;20(3):278–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1204072.

Wong KK, Maser RS, Bachoo RM, Menon J, Carrasco DR, Gu Y, et al. Telomere dysfunction and Atm deficiency compromises organ homeostasis and accelerates ageing. Nature. 2003;421(6923):643–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01385.

Arnoult N, Karlseder J. Complex interactions between the DNA-damage response and mammalian telomeres. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(11):859–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3092.

Chen H, Ruiz PD, McKimpson WM, Novikov L, Kitsis RN, Gamble MJ. MacroH2A1 and ATM play opposing roles in paracrine senescence and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Mol Cell. 2015;59(5):719–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.011.

Kang C, Xu QK, Martin TD, Li MZ, Demaria M, Aron L, et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science. 2015;349(6255):1503-+. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa5612.

Aird KM, Worth AJ, Snyder NW, Lee JV, Sivanand S, Liu Q, et al. ATM couples replication stress and metabolic reprogramming during cellular senescence. Cell Rep. 2015;11(6):893–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.014.

Cosentino C, Grieco D, Costanzo V. ATM activates the pentose phosphate pathway promoting anti-oxidant defence and DNA repair. EMBO J. 2011;30(3):546–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.330.

Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Takubo K, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto K, et al. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12(4):446–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1388.

Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Hamaguchi I, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431(7011):997–1002. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02989.

Liang R, Ghaffari S. Stem cells, redox signaling, and stem cell aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(12):1902–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5300.

Sato A, Okada M, Shibuya K, Watanabe E, Seino S, Narita Y, et al. Pivotal role for ROS activation of p38 MAPK in the control of differentiation and tumor-initiating capacity of glioma-initiating cells. Stem Cell Res. 2014;12(1):119–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2013.09.012.

Bhattacharya R, Mustafi SB, Street M, Dey A, Dwivedi SK. Bmi-1: at the crossroads of physiological and pathological biology. Genes Dis. 2015;2(3):225–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2015.04.001.

Li J, Herrup K. Alterations in epigenetic systems in AT neurodegeneration. Biohelikon Cell Biol. 2013;1:1–2.

Consalvi S, Brancaccio A, Dall’Agnese A, Puri PL, Palacios D. Praja1 E3 ubiquitin ligase promotes skeletal myogenesis through degradation of EZH2 upon p38alpha activation. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13956. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13956.

Feng X, Juan AH, Wang HA, Ko KD, Zare H, Sartorelli V. Polycomb Ezh2 controls the fate of GABAergic neurons in the embryonic cerebellum. Development. 2016;143(11):1971–80. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.132902.

Kim J, Wong PK. Loss of ATM impairs proliferation of neural stem cells through oxidative stress-mediated p38 MAPK signaling. Stem Cells. 2009;27(8):1987–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.125.

Kim J, Hwangbo J, Wong PK. p38 MAPK-Mediated Bmi-1 down-regulation and defective proliferation in ATM-deficient neural stem cells can be restored by Akt activation. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16615. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016615.

Harbort CJ, Soeiro-Pereira PV, von Bernuth H, Kaindl AM, Costa-Carvalho BT, Condino-Neto A, et al. Neutrophil oxidative burst activates ATM to regulate cytokine production and apoptosis. Blood. 2015;126(26):2842–51. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-05-645424.

Kondo T, Kobayashi J, Saitoh T, Maruyama K, Ishii KJ, Barber GN, et al. DNA damage sensor MRE11 recognizes cytosolic double-stranded DNA and induces type I interferon by regulating STING trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(8):2969–74. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222694110.

Ahn J, Xia T, Konno H, Konno K, Ruiz P, Barber GN. Inflammation-driven carcinogenesis is mediated through STING. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5166. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6166.

Yu Q, Katlinskaya YV, Carbone CJ, Zhao B, Katlinski KV, Zheng H, et al. DNA-damage-induced type I interferon promotes senescence and inhibits stem cell function. Cell Rep. 2015;11(5):785–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.069.

Petersen AJ, Katzenberger RJ, Wassarman DA. The innate immune response transcription factor relish is necessary for neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of ataxia–telangiectasia. Genetics. 2013;194(1):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.113.150854.

Quek H, Luff J, Cheung K, Kozlov S, Gatei M, Lee CS, et al. A rat model of ataxia–telangiectasia: evidence for a neurodegenerative phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddw371.

Pereira-Lopes S, Tur J, Calatayud-Subias JA, Lloberas J, Stracker TH, Celada A. NBS1 is required for macrophage homeostasis and functional activity in mice. Blood. 2015;126(22):2502–10. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-04-637371.

Bednarski JJ. DNA damage signals inhibit neutrophil function. Blood. 2015;126(26):2773–4. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-678672.

Herrtwich L, Nanda I, Evangelou K, Nikolova T, Horn V, Sagar, et al. DNA damage signaling instructs polyploid macrophage fate in granulomas. Cell. 2016;167(5):1264-80 e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.054.

Wang Q, Franks HA, Lax SJ, El Refaee M, Malecka A, Shah S, et al. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase pathway regulates IL-23 expression by human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3246–55. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1201484.

Li S, Zhang L, Chen T, Tian B, Deng X, Zhao Z, et al. Functional polymorphism rs189037 in the promoter region of ATM gene is associated with angiographically characterized coronary stenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):694–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.040.

Su Y, Swift M. Mortality rates among carriers of ataxia–telangiectasia mutant alleles. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(10):770–8.

Figueiredo N, Chora A, Raquel H, Pejanovic N, Pereira P, Hartleben B, et al. Anthracyclines induce DNA damage response-mediated protection against severe sepsis. Immunity. 2013;39(5):874–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.039.

Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(8):973–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1909.

Chen WT, Ebelt ND, Stracker TH, Xhemalce B, Van Den Berg CL, Miller KM. ATM regulation of IL-8 links oxidative stress to cancer cell migration and invasion. eLife. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.07270.

Quick KL, Dugan LL. Superoxide stress identifies neurons at risk in a model of ataxia–telangiectasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(5):627–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Thiago Mattar Cunha.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zaki-Dizaji, M., Akrami, S.M., Azizi, G. et al. Inflammation, a significant player of Ataxia–Telangiectasia pathogenesis?. Inflamm. Res. 67, 559–570 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-018-1142-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-018-1142-y