Abstract

Phosphorus availability may shape plant–microorganism–soil interactions in forest ecosystems. Our aim was to quantify the interactions between soil P availability and P nutrition strategies of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) forests. We assumed that plants and microorganisms of P-rich forests carry over mineral-bound P into the biogeochemical P cycle (acquiring strategy). In contrast, P-poor ecosystems establish tight P cycles to sustain their P demand (recycling strategy). We tested if this conceptual model on supply-controlled P nutrition strategies was consistent with data from five European beech forest ecosystems with different parent materials (geosequence), covering a wide range of total soil P stocks (160–900 g P m−2; <1 m depth). We analyzed numerous soil chemical and biological properties. Especially P-rich beech ecosystems accumulated P in topsoil horizons in moderately labile forms. Forest floor turnover rates decreased with decreasing total P stocks (from 1/5 to 1/40 per year) while ratios between organic carbon and organic phosphorus (C:Porg) increased from 110 to 984 (A horizons). High proportions of fine-root biomass in forest floors seemed to favor tight P recycling. Phosphorus in fine-root biomass increased relative to microbial P with decreasing P stocks. Concomitantly, phosphodiesterase activity decreased, which might explain increasing proportions of diester-P remaining in the soil organic matter. With decreasing P supply indicator values for P acquisition decreased and those for recycling increased, implying adjustment of plant–microorganism–soil feedbacks to soil P availability. Intense recycling improves the P use efficiency of beech forests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The functioning of terrestrial ecosystems depends on P availability (Achat et al. 2016) but quantitative knowledge regarding its relationship to soil P stocks is missing. Results obtained from studies along chronosequences showed that aboveground and belowground P pools of ecosystems reflect the current state of interactions between P availability of soils and P uptake and usage by plants and microorganisms occurring at these sites (Pearson and Vitousek 2002; Selmants and Hart 2010; Turner and Condron 2013; Galván-Tejada et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014). These studies suggest that the P contents of the parent material affect the development of ecosystems, especially in the soil compartment, based on different P-related plant–microorganism–soil interactions. According to Odum’s hypothesis on the nutrition strategies of vegetation, P cycles tend to “tighten” during succession (Odum 1969): young ecosystems are characterized by open P cycles; mature ecosystems establish closed P cycles. The rate of changes in P pools with succession likely depends on the parent material of the soils (Laliberté et al. 2013). Recently, the role of the parent material in the P nutrition of terrestrial ecosystems has thus gained more and more attention (Augusto et al. 2017). Based on their analyses of the P contents of different types of parent material, Porder and Ramachandran (2013) outlined the need for quantifying links between the P content of the parent material and ecosystem P dynamics. Owing to our limited understanding of the underlying processes, it is currently not possible to predict, how P nutrition strategies of late successional forest ecosystems are controlled by the P supply from parent material.

The recent decline in P nutrition of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) documented in several publications (e.g., Talkner et al. 2015) has intensified the scientific debate about possible underlying mechanisms (Jonard et al. 2015). So far no consensus has been reached and many open questions remain regarding the P nutrition of beech forests. Natural F. sylvatica forests cover a wide range of soils, which mainly formed since the last ice age and developed from various parent materials (Peters 1997). The prevalence of F. sylvatica ecosystems in Central Europe enables exploring the P nutrition strategies of plant and microbial communities with different soil P contents but similar state of forest development. This provides an opportunity to test the conceptual model, that P stocks in parent material control P nutrition of mature forest ecosystems (Lang et al. 2016). According to this model, plant and microbial communities at P-rich sites transfer P from soil minerals into the biogeochemical P cycle. The set of mechanisms involved in this transfer is what we term P acquiring strategy. In contrast, tight P cycling is expected at sites poor in P. That means plants and microbes use P from organic sources and minimize P losses from the biogeochemical cycle. The set of mechanisms contributing to this tightening of the P cycle is what we term P recycling strategy. The aim of our study was to test if this conceptual model of supply-controlled P nutrition is consistent with analytical data obtained from beech forest ecosystems. Additionally, we addressed the question of how P acquisition and recycling changes with changing P supply. First, we analyzed a variety of P-related ecosystem properties of beech forest ecosystems at sites with different parent materials, covering a wide range of different P stocks. Second, we quantified indicator values for the proposed P nutrition strategies and related them to the P soil stocks of the five study sites.

To the best of our knowledge, the study design as well as the diversity of analyses applied is unprecedented: we studied five forest ecosystems dominated by the same tree species but differing in P stocks of soils by a factor of six. In contrast to the concept of chronosequences, the sites represent a geosequence with different P contents in the parent material and are spatially independent. The chemical analyses covered a wide range of P forms, included soil stocks at high depth resolution down to 1 m, as well as P mobilization kinetics. These analyses were combined with analyses of microbiological and root characteristics as well as P concentrations in beech leaves and permitted the solid analysis of soil–plant–microorganism interactions in beech forest ecosystems along the P geosequence. Based on these data and on a novel indicator approach we provide evidence that P nutrition strategies of beech forests adapt continuously to changing P stocks.

Materials and methods

Study sites

We selected five study sites differing in their parent material and supporting 120–140 year old beech forests (Table 1). Methods used for analyzing stand characteristics are summarized in supplementary S1. The parent material ranged from P-rich basaltic rock (Porder and Ramachandran 2013) to P-poor sandy till (Table 1). All sites were in periglacial zones during the last glaciation in central Europe (Fiebig et al. 2011; Geyer and Gwinner 1986; Ergenzinger 1967). Thus, the development of the present soil profiles started at the end of the last ice-age, 10–12,000 years ago (Eberle and Allgaier 2010). All study sites are Level II intensive monitoring plots of the Pan-European International Co-operative Program on assessment and monitoring of air pollution effects on forests (ICP Forests) under UNECE (Lorenz 1995; Vries et al. 2003). Soil and tree properties have been monitored for the last 15–25 years. Four sites (Bad Brückenau, BBR; Mitterfels, MIT; Vessertal, VES; Conventwald, CON) are located at intermediate elevation in the German central and southern uplands; the P-poorest site Lüss (LUE) is located in the North German lowlands.

Sampling design

The characterization of forest stands, vegetation, and litterfall was performed according to the ICP Forest manual at a monitoring plot with an area of 0.25 ha representing the forest stand. The analyses of microbial biomass were performed with samples from soil cores derived from five sampling points distributed within the buffer zone around the monitoring plot (see below). For the other soil analyses, we used soil samples derived from volume based sampling of a complete soil profile performed over an area of 0.25–0.56 m2, down to 90–100 cm below the mineral soil surface. Due to the high stone contents of the soils, we decided to use the “quantitative soil pit” (QP) approach developed by Hamburg (1984) and adjusted recently by Vadeboncoeur et al. (2012) to quantify carbon (C) stocks in stony forest soils. The method provides volume-based samples of fine earth material and other constituents, such as roots and stones, of a soil pit. By analyzing a soil volume with a large cross section representing a large portion of the rooting space of an adult tree, QP sampling allows to obtain a more coherent picture of the system than by analyzing several small soil volumes.

The QPs were established in the buffer zone of the monitoring plots within the Level II sites. Only one QP per study site could be established. The exact position was determined randomly but had to meet the following criteria: (1) thickness of forest floor and distribution of mineral soil horizons representative for the forest stand (identified based on auger screening of the monitoring site), (2) a minimum distance of at least 3 m to the next trees (diameter at breast height (DBH) >10 cm), and (3) not covered by understory or downed deadwood.

Soil sampling and fractionation

For quantitative pit establishment, a square wooden frame with an interior lateral length of 50 cm (75 cm at site BBR) was prepared and registered optical targets for photogrammetric analysis were fixed to the upper side of the frame. The frame was fixed as reference plane to the soil surface using steel pins. The entire organic layer was cut off alongside the inner edge of the frame with a knife. The individual humus layers (Oi, Oe, Oa) were sampled separately by hand. Roots crossing different layers were cut off at the layer boundary and removed to prevent mixing of material from different layers. The mineral soil sampling followed layers representing single diagnostic horizons. If the thickness of a diagnostic horizon exceeded 5 cm for A or E horizons and 10 cm for B horizons, a new sample layer was started. The procedure was repeated until a maximum sampling depth of 1 m was reached. Following this procedure, we obtained 10 (BBR) to 15 (MIT and VES) different depth layers per site. Detailed information on soil sampling depths at the different sites is given in the supplementary material (S2). All soil material (including rocks and roots) was placed in containers, transported to the laboratory, and air-dried (40 °C). Then, the soil samples were manually separated into the following fractions: fine earth (<2 mm), gravel (2–20 mm), stones (>20 mm), coarse roots (>2 mm), fine roots (<2 mm), and other soil constituents (e.g., wood or seedlings). All fractions were weighed and stored dry, cold, and in the dark for further analysis. Dried fine earth material was used for soil analyses. The volume quantification of the different soil layers was carried out based on photogrammetry (Haas et al. 2016).

For microbiological analyses, five contiguous soil cores (circular distance 2–3 m) were taken and the Oe and Oa horizons removed before samples were pooled together and sieved to 2 mm. This procedure was conducted five times giving five pooled soil samples per site. Soil samples were stored at 4 °C prior to analysis.

The analyses of the bulk samples from the quantitative pits were conducted in duplicate (soil chemical analyses) or triplicate (analyses of enzyme activity) to account for analytical variability. The mean coefficients of variation of the analyzed soil samples were below 10% and indicate good reproducibility of applied methods. We do not have exact information regarding the spatial heterogeneity of all the analyzed properties across study sites. However, there are clear indications that the results obtained from QP sampling represent the study site properties: (1) QP location was determined based on a soil survey of the study area (see description above). (2) In frame of a geostatistical analysis, we determined citrate extractable P concentrations, carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratios, and pH values of the forest floor and three soil depth increments at 48 sampling points within 50 × 50 m areas at four of the study sites (LUE, CON, MIT, BBR). The results for the pit samples were mostly within the 68% confidence range of the grid data for the analyzed soil properties and soil horizons (results not shown). (3) We analyzed 10–15 depth intervals at the different sites and outliers would have been identified based on extraordinary discontinuities of analyzed soil properties along the depth gradient. (4) Total P concentrations are assumed to be controlled by the P content of the parent soil material (Turner and Engelbrecht 2011), which is homogeneous within the study sites. Furthermore, published information on the heterogeneity of P concentrations in soil within an area of uniform morphology and geology pointed to only small variation with coefficients of variation less than 10% (e.g., Turner et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2015).

Basic soil chemical characterization

Total contents of soil C and N were measured on ground samples dried at 105 °C using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL cube, Elementar, Germany). Soil pH of air-dried samples (40 °C) was determined in deionized water and in 1 M KCl at a soil-to-solution ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v).

Determination of the cation exchange capacity (CEC) and exchangeable cations was carried out using ammonium acetate at pH 7 and KCl (Hendershot et al. 2008). Concentrations of extracted Ca, Mg, K, and Na were determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Ultima 2, Horiba Jobin–Yvon S.A.S., Longjumeau, France); ammonium in KCl extracts was determined using an automated photometer (SANplus, Skalar Analytical B.V., Breda, The Netherlands). The difference between the CEC and the sum of Ca, Mg, K, and Na is an estimate of H+ and Al3+ occupation of the CEC.

The hot dithionite–citrate–bicarbonate extraction of Fe (FeDCB), as outlined by Mehra and Jackson (1960), was used to estimate total pedogenic Fe oxide phases. Extraction with NH4 oxalate at pH 3.0 and 2 h shaking in the dark (Schwertmann 1964) was carried out to estimate Al and Fe in short range-ordered forms and organic complexes (Alox and Feox). The concentrations of extracted Al and Fe were determined by ICP-OES.

Soil phosphorus analyses

Total P, citrate extractable P, and organic P

Contents of total soil phosphorus were determined on ground samples dried at 105 °C after microwave-digestion with 42% HF and H2O2 (both: Suprapur©, Merck Millipore, Germany) using ICP-OES (CIROS CDD, Side-On plasma, Spectro, Germany). Organic acid extraction for the quantification of plant-available P in soils has been recommended to simulate organic acid secretion by plant roots (Gerke and Hermann 1992). We analyzed plant-available P by extraction of sieved subsamples with 1% citric acid (50 mM citrate). Similar as described by Hayes et al. (2000), we used a soil-to-solution ratio of 1:10 (w/v), and determined orthophosphate-P concentrations using the ascorbic acid method of Murphy and Riley (1962) as modified by John (1970). Total extractable P was quantified by ICP-OES analyses. Organic P (Porg) in soil samples was analyzed using the ignition method of Saunders and Williams (1955). Each sample was extracted with or without preceding ignition at 550 °C with 0.5 M H2SO4 and the fraction of Porg was quantified as difference of extracted orthophosphate quantified using the malachite green colorimetric method (Ohno and Zibilske 1991). We used Porg obtained by the method of Saunders and Williams for calculating the C:Porg ratios of soil organic matter. Uncertainties related to this approach are discussed in supplementary material S3.

Hedley fractionation

Soil samples were analyzed by sequential extraction according to Hedley and Stewart (1982) as modified by Tiessen and Moir (2008). We used 24 samples in one batch consisting of 23 individual samples including six replicate samples (as random quality check) and one in-house soil standard for quality testing. Each 0.5 g soil was extracted with solutions of increasing extraction strength, starting with distilled water containing an anion exchange resin (Dowex 18, 20–50 mesh, Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), followed by 0.5 M NaHCO3; 0.1 M NaOH; 1 M HCl; HCl (37%w/w) and a final acid digestion with 65% HNO3 and 30% H2O2. Orthophosphate-P concentrations of the different extracts were determined photometrically (Murphy and Riley 1962). We combined the different fractions according their mobility and speciation (organic vs. inorganic P) to describe the following P pools:

Sorbed inorganic P: inorganic P extractable by resin, NaHCO3, and NaOH and sorbed organic P: organic P extractable by NaHCO3 and NaOH, Ca-phosphates: the P fraction mobilized by 1 M HCl; stable P: sum of the P fractions dissolved by HCl (conc) or acid digestion.

Solution-state 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

For solution-state 31P-NMR analyses, three soil horizons (Ah horizons, as well as two B horizons from about 30 and 90 cm soil depth) were extracted using 0.25 M NaOH plus 0.05 M Na2EDTA (1:1/v/v), as described by Cade-Menun (2005). Samples were thereafter centrifuged (1500×g, 20 min), and the remaining supernatant was then split into two halves. One half was lyophilized directly (Thermo Freeze Dryer, Heto PowerDry PL6000). The second half of the supernatant was dialyzed (molecular weight cut off, MWCO, was 14,000; thickness 0.041 mm; Visking, Cellulose, Roth, (Sumann et al. 1998; Amelung et al. 2001). To prepare the samples for NMR spectroscopy, the freeze-dried extracts were resolved by 1 ml aqua dest., 0.5 ml of D2O, and 10 M NaOH to increase and to standardize the pH for optimal peak separation (Crouse et al. 2000). Samples were centrifuged (1500×g, 20 min) und decanted into NMR tubes.

Spectra were recorded on an NMR spectrometer (Inova 400, Varian, USA) with power-gated proton decoupling at a temperature of 295 K. An acquisition time of 0.7 s, a 30° pulse, and 0.5 s of relaxation delay were used. Chemical shifts of signals were measured in parts per million (ppm) relative to 85% orthophosphoric acid. Approximately 24,576 scans were acquired for each sample. Spectra for the soil samples were recorded with a line broadening of 3.0 Hz. Terminology and interpretations of the spectra followed Cade-Menun (2005, 2015), Bol et al. (2006), Vincent et al. (2013). The chemical shift of the spectra was analyzed as described by Turner (2004). Further details and a discussion of uncertainties are provided in the supplementary material (S4).

Isotopic exchange kinetic

Briefly, a given amount of H 333 PO4 was added to a soil water suspension pre-equilibrated (steady-state conditions for P) and the decrease of radioactivity remaining in the solution was measured over time. At the end of the experiment (after 80 min for all samples except for LUE, AE, for which the experiments lasted 420 min because of the very low rate of isotopic exchange), the concentration of orthophosphate in the solution (C P ) was measured after centrifugation for 10 min at 10 000 g and filtration at 0.2 µm using the malachite green colorimetric method (Ohno and Zibilske 1991). Isotopic exchange kinetic (IEK) experiments were detailed by Fardeau 1993, 1996) and Randriamanantsoa et al. (2013). The decrease with time of the 33P added in solution can be described by the following equation (Fardeau 1993):

where r t and r ∞ (MBq) are the radioactivity remaining in solution after t min of exchange and after an infinite time of exchange, respectively; R (MBq) is the initially added radioactivity; t is the time (in min) elapsed after the radioactivity addition and m and n are soil specific parameters calculated from a non-linear regression between r t /R and t. The r ∞ /R value is estimated as the ratio of the water soluble P expressed in mg P kg−1 to the total inorganic P. The amount of water soluble P is calculated as 10 × C P , with C P expressed in mg P l−1 and 10 being the solution to soil ratio (100 ml:10 g).

As described by Fardeau (1993) the amount of soil isotopically exchangeable P (E t , expressed in mg P kg−1 soil) is calculated based on Eq. 2:

The following variables were calculated for selected samples (Fardeau 1993): m, n, C P , and the amounts of P isotopically exchangeable within 1 min (E 1 min, mg P kg−1 soil), between 1 min and 1 day (E 1 min–1 day), between 1 day and 3 months (E 1 day–3 months), and the amount of P that cannot be exchanged within 3 months (E >3 months) by taking the difference between total inorganic P and E 3 months. The samples were analyzed in duplicate.

Fine roots

Fine-root biomass was quantified as described above. Fine roots (<2 mm diameter) were weighed and used for mycorrhizal analyses. All root tips of each weighed sample were inspected under a dissecting microscope (M205 FA; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and classified as vital non-mycorrhizal, vital mycorrhizal or dead. The percentage of mycorrhizal colonization was calculated as (n vital mycorrhizal root tips/n vital root tips) × 100. Vital root tips were distinguished from dead and dry root tips according to the method used by Winkler et al. (2010). Root tip vitality (%) was calculated (n vital root tips/n total root tips) × 100. For the determination of P concentration in fine roots, fine root material was washed, ground and digested by HNO3 (65% w/w). Phosphorus concentrations were analyzed by ICP-OES (CIROS CDD, Side-On plasma, Spectro, Germany).

Microorganisms

Quantification of microbial biomass

Soil samples (A horizon) were extracted according to Brankatschk et al. (2011) for estimation of microbial biomass C (Cmic), N (Nmic), and P (Pmic). Measurements of Cmic and Nmic were performed using the chloroform fumigation-extraction (CFE) method according to Vance et al. (1987), Joergensen (1996) (k EC 0.45) and Joergensen and Mueller (1996) (k EN 0.54). For determination of microbial biomass P the CFE-method modified from Brookes et al. (1982) (k EP 0.4) was applied. Since Cmic, Nmic and Pmic were intended to be compared from the same extract, 0.01 M calcium chloride was used instead of 0.5 M sodium hydrogen carbonate for inorganic-P extraction. Orthophosphate was quantified as molybdenum blue using commercial tube tests “NANOCOLOR ortho- and total-Phosphate 1″ (Macherey–Nagel, Germany).

Determination of acid phosphomonoesterase and phosphodiesterase activities

Acid phosphomonoesterase (EC 3.1.3.2) activity was determined using a modified disodium phyenylphosphate method. Briefly, each soil sample (field-moist samples, stored at −20 °C and sieved) was split into three subsamples and two controls of 1 g each. Soil suspensions were prepared with 10 ml acetate buffer (pH 5) and 5 ml of 20 mM disodium phenylphosphate (EC 3279-54-7) as substrate solution; in controls, substrate solution was replaced by deionized water. All soil suspensions were incubated at 37 °C and continuous shaking (100 rpm) for 3 h. The release of phenol was determined colorimetrically at 614 nm (ELx808, Absorbance Microplate Reader, BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA), using 2,6-dibromchinone-chlorimide (EC 202-937-2) as coloring reagent (Hoffmann 1968, modified by Öhlinger 1996).

The activity of phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.1) was measured using bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate (EC 223-739-2) as substrate and ris(hydroximethyl)aminomethane as the p-nitrophenol color reagent, according to a modified procedure of Margesin (1996). Each fresh soil sample was split into three subsamples and two controls of each 1 g. Soil suspensions were prepared with 4 ml of 0.05 M Tris(THAM) buffer (pH 8.0) and 1 ml of 5 mM substrate solution; in controls, substrate solution is replaced by deionized water. Soil suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h at continuous shaking (100 rpm). After incubation, 1 ml 0.5 M NaCl solution and 4 ml 0.1 M Tris(THAM) buffer (pH 12.0) were added to each subsample, whereas the controls received additionally 1 ml of the substrate solution. Soil suspensions were filtered and pipetted into 96-well microplate (PS F transparent 96 well; Greiner Bio-one GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany). The enzyme activity was measured photometrically at 405 nm on a microplate reader (ELx808, Absorbance Microplate Reader, BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Leaves and litterfall

P concentrations of beech leaves

Current year beech leaves were sampled in July/August from five trees (9 at LUE). South-facing branches from the upper third of the crown were selected (Rautio et al. 2010). Leaf material was washed, ground and digested by HNO3 (65%w/w). Phosphorus concentrations were analyzed by ICP-OES. Mean values for leaves from 3–5 years of sampling (between 1995 and 2013, integrating mast years and non-mast years) are presented.

Litterfall

Litterfall at the study sites except VES, where no litterfall sampling took place, was determined according to Pitman et al. (2010) using 10 (12 at LUE) litter collectors distributed among the monitoring plot. Each litter collector had an area of 0.25 m2. Litterfall was collected monthly and in periods of strong litterfall bi-weekly. Values presented here represent the sampling period 2013. For litter weight documentation the total mass of litter was determined. P concentrations were only determined for the leaf component of litter fall.

Indicators for P acquisition and P recycling

The most direct approach for testing the hypothesis that soil P stocks control the P nutrition strategy of beech forest ecosystems would be analyzing the P fluxes within the soil and from soil to plants and microorganisms. Some of the relevant P fluxes are hard to quantify (Bol et al. 2016) and not yet available at the study sites. However, the different P nutrition strategies can modify the studied P characteristics of the ecosystems as well as other ecosystem properties. Based on current knowledge and theoretical assumptions we used indicators to assess P nutrition strategies. We defined three indicators for P acquisition and four indicators for P recycling and analyzed how indicator values were related to the soil P stocks at the study sites. Regarding P recycling we selected properties indicating tight cycling of P between plants and the organic soil P pool. We did not consider plant internal P cycling here although it had been shown to be important for the nutrition of European beech at P poor sites (Netzer et al. 2017). The indicators used are listed and their justifications given in Table 2. The table also informs on the way the indicator values were calculated. In general, indicators representative of acquiring systems address P mobilization from the mineral soil and indicators representative of recycling systems refer to P associated with soil organic matter. To enable the comparison of the different indicators along the geosequence, we normalized all the different indicator values according to Eq. 3:

where N represents the normalized indicator value, the index a represents the indicator addressed, the index i represents the study site, I represents the indicator value, and the index m represents the P-richest site (= BBR) for acquisition indicators and the P-poorest site (= LUE) for recycling indicators.

In addition, we calculated the P uptake efficiency of beech trees according to Marschner et al. (2015) based on Eq. (4):

where Nutrientleaves is the P stock in beech leaves and Nutrientsoil the P stock in entire soil profile. The P stock of beech leaves was estimated based on the P concentration of the leaves and the annual litterfall.

Results

Analyses of the soils’ solid phase

Variation of basic soil properties along the geosequence

Total P stocks down to 1 m depth of the mineral soil of the geosequence differed by a factor of 5.6 between the poorest site LUE and the richest site BBR (Table 3, supplementary material S5). The P concentrations in topsoil horizons even differed by a factor of 27 among sites (supplementary material, S5). Nearly all extraction methods confirmed the P gradient for the first meter of the soil profile: BBR > MIT ≥ VES > CON > LUE. The soils of all study sites were acidic (Table 3, supplementary S2) and showed intermediate to high contents of organic C (C org ). Soil textures were mostly loam, apart from the P-poorest site LUE with a loamy sand texture. The plant availability of the major nutrients, as indicated by C:N ratio or exchangeable cations, differed strongly among the sites. Although total N contents of the sites were significantly related to P contents (r2 = 0.74; p < 0.05), there was still a considerable variation in N/P ratios. The difference in P-related soil properties was larger than that of all the other properties (Table 3).

The depth distribution of P in the soils

Soil P concentrations in the forest floor horizons covered a much smaller range than in the mineral soil horizons (Fig. 1; e.g., Oe horizons: 847–1570 mg kg−1; A horizons: 196–3265 mg kg−1). Consequently, the portion of P located in the forest floor increased with decreasing P in the mineral soil but was generally rather small (0.4 to 9.2% of total P stock; supplementary material S5). In addition, the mass of forest floor material tended to increase along the P geosequence while its turnover rate decreased continuously (Table 4). In the mineral soil, we observed decreasing concentrations of total P with increasing soil depth at all sites; the decrease was more pronounced at P-rich than at P-poor sites (Fig. 1). While the soil profiles at MIT and LUE indicate vertical translocation of Al and Fe, no such re-location of P could be observed (S6).

Phosphorus fractionation and speciation

Phosphorus concentrations of all Hedley fractions analyzed decreased along the P geosequence with decreasing total soil P stocks (supplementary material S7). Most pronounced with decreasing soil P stocks was the increase in P in the HCl(conc) and residual P fractions (supplementary material S7). These two fractions contributed up to 20% of the total P at the P-richer sites BBR, MIT and VES. In contrast, they accounted for more than 35% in topsoil horizons and up to 60% of total P in subsoil horizons at the P-poor sites. The stocks of the P fractions at the different sites also highlighted the increasing proportion of the stable P fractions with decreasing total P stock (Fig. 2). In the subsoil horizons, organic Hedley fractions were greater at sites BBR and MIT than at the P-poor sites CON and LUE (supplementary material S7). The sum of both organic Hedley fractions corresponded well with the results obtained by the method of Saunders and Williams (1955, see below).

The percentage of organic P of the mineral soils decreased with increasing soil depth and decreasing C org concentration. Regarding the share of Porg of the total P stock of the soil profiles, we observed slightly lower contributions of Porg at the two sites lower in P (CON and LUE; P org contributes 26% to total P) than at the three sites at the upper end of the P gradient (Porg contributed 38–44–38% to total P stock). While there was no clear trend in the percentage of P org in the different horizons along the P geosequence, the C:Porg ratio of the mineral soil increased significantly with decreasing P status, which was most pronounced for the A horizons (Table 5). For the sites BBR, MIT, VES and CON, the C:P org ratio declined with increasing soil depth; at the site LUE the C:Porg ratio increased from the Oe to the AE horizon and decreased only beneath.

NMR data showed that the most prominent organic P species were diesters and monoesters (Table 6). The dialyzed EDTA/NaOH extracts contained between 35.6 and 85.2% of monoester-P and between 6.4 and 33.6% of diester-P. Despite the preceding dialysis, the NMR spectra, however, also revealed that the samples contained up to 15% orthophosphate-P. In addition, the samples contained traces of polyphosphate-P (1%, detected in surface soils only) and pyrophosphate-P (6%). Unusually large portions of phosphonate-P were detected, which reached 22% of total signal intensity in the topsoil material at LUE (Table 6). In addition, the spectra of topsoil samples showed increasing proportions of diester-P with decreasing P stock. The increase in diester-P went along with an increase in phosphonate-P, while the proportions of monoester-P declined correspondingly. The ratio of diester-P/monoester-P increased in the same direction: BBR < MIT = VES < CON < LUE (Table 6).

Phosphorus mobilization kinetics by isotopic exchange

The concentrations of water-extractable inorganic P (CP) ranged between 1.3 and 0.01 mg P L−1 in the LUE AE and the CON BA horizons, respectively (Table 7). In all soils, CP values decreased with increasing depth. The loss rate of 33P radioactivity from solution in these laboratory experiments was described using two fitting parameters (Eq. 1). The fitting parameter m followed the same trends as CP. The fitting parameter n was between 0.4 and 0.8 in all samples except those from LUE where values were much lower. The amount of P isotopically exchangeable between 1 min and 3 months (E1 min–3 months) in the topsoil horizon decreased in the order BBR > MIT > CON > VES > LUE, for LUE it was very little. In contrast, the amount of P isotopically exchangeable within 1 min in the AE horizon of LUE was nearly as high as that in the Ah1 horizons of VES and MIT.

Trees and soil microorganisms

Leaves and litter fall

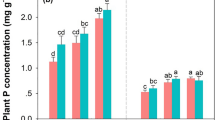

Despite the strong differences in P stocks and availability, above-ground woody biomass was similar among the sites. The P concentrations of beech leaves decreased only slightly with decreasing P stocks in soils (Table 4). Leaf litter P was slightly higher at BBR and MIT than at CON and LUE (Table 4). The decrease in leaf litter P concentrations was much steeper than the decrease in the P concentrations of living leaves (Table 4).

Fine roots

The total fine-root biomass per area slightly increased along the geosequence (BBR 815 mg m−2, MIT 1160 mg m−2, VES 1098 mg m−2, CON 923 mg m−2, LUE 1668 mg m−2). Concentrations of P in fine roots were lower than in leaves (Table 4). Especially at the P-poor sites CON and LUE, root P concentrations in mineral soil horizons were much lower than those of fine roots in the forest floor (Table 4). In addition, root biomass was increasingly concentrated in the forest floor and topsoil horizons with decreasing soil P stocks. Only 20% of the total fine-root biomass within the top meter of the soil profile was located in the forest floor and the A horizon at the P-rich site BBR; the respective share increased to nearly 70% at the P-poor site LUE (Fig. 3). The degree of mycorrhization of the vital root tips was 100% across all sites and soil horizons. Root vitality was similar along all study sites, but showed decreasing vitality with increasing soil depth, starting at 60–70% in the forest floor and topsoil horizons and decreasing to about 30–40% in the subsoil horizons.

Microbial biomass

Highest microbial biomass P (Pmic) in the topsoil was detected at site MIT (111 µg g−1), followed by CON (104 µg g−1), BBR (100 µg g−1), and VES (79 µg g−1); LUE showed the lowest values (10 µg g−1). Regarding Cmic and Nmic, a different order was observed. While LUE again had consistently low values; Cmic and Nmic reached maxima at the sites CON and BBR (Table 8). The mass ratios of microbial C and P (Cmic:Pmic) decreased from 20 at LUE to seven at MIT (Table 8). The latter soil likewise showed the lowest ratios of Nmic:Pmic (0.7) and Cmic:Nmic (10); highest values were detected at CON (1.3) and LUE (16). In summary, Nmic:Pmic and Cmic:Pmic ratios did not strictly follow the P contents of the soils, with the P-richest site of the geosequence (BBR) having larger Nmic:Pmic and Cmic:Pmic ratios in the Ah horizon than the P-poorer sites MIT and VES. At all sites, the C:P ratios of microorganisms were much smaller than the C:P ratio of soil organic matter. The imbalances between soil organic matter and microbial ratios increased with decreasing P contents of the soil (Table 8).

Enzyme activities involved in P mineralization

Phosphomonoesterase activity (supplementary S8) was much higher in the forest floor material than in all mineral soil samples. This was also true for phosphodiesterase activity (S8). Phosphomonoesterase activities decreased more strongly from forest floor to the mineral soil than phosphodiesterase activities, resulting in smaller monoesterase:diesterase ratios in the mineral soil than in the forest floor, except for LUE (Fig. 4). Phosphomonoesterase activities of soil samples from different soil horizons were closely related to fine-root biomass, with site-specific slopes (data not shown). In contrast, phosphodiesterase activities were related to microbial biomass (r2 = 0.81; p < 0.05).

Discussion

Solid phase properties

The range of soil properties covered by the P geosequence

The study sites differed clearly in total P stocks of the mineral soils. The range in P stocks and concentrations in the soils (fine-earth fractions) was as large as the range covered by published chronosequence studies (Table 3, supplementary material S5). The P supply by the soil fine-earth material roughly mirrored the P level of the parent material as described by Porder and Ramachandran 2013. The P contents of the parent materials as well as pedogenic processes seem to control the total P stocks of the soils at the different study sites.

Phosphorus associated to Al and Fe oxy(hydr)oxides

Iron and Al oxy(hydr)oxides are important sorbents for inorganic and organic P components. This role was confirmed for the sites BBR, MIT, and CON by P K-edge XANES analyses (Prietzel et al. 2016). At all sites, the amount of oxalate-extractable Al and/or Fe increased—at least slightly—with increasing soil depth, indicating beginning podsolization (Lundström et al. 2000). Podsolization was most obvious at the site LUE. Nevertheless, P was not leached together with Fe and Al but it was incorporated into organic P fractions (supplementary material S7). In consequence, the degree of P saturation of the soil sorbents decreased with increasing soil depth (S6). In contrast, several studies showed translocation of P by podsolization (Turner et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2014; Celi et al. 2013; Wood et al. 1984), especially in cold temperate climate (Väänänen et al. 2008). Also Backnäs et al. (2012) observed P translocation from topsoil to subsoil horizons during podsolization. At their study site in Southern Finnish Lapland, tree growth was much less intense than at our most strongly podsolized site LUE. While the volume of the tree stand at Lapland was 70 m3 ha−1, for instance, it amounted to 529 m3 ha−1 at site LUE. Consequently, the lack of translocation of P at site LUE could be due to stronger biological uptake. Quantifying the true magnitude and thus significance of P fluxes within the soil profiles warrants further attention (see also Bol et al., 2016).

Organic P

The percentage of P org in soils has been assumed to be an emergent property representing complex interactions within the ecosystem (Turner and Engelbrecht 2011). The mean values for the proportion of P org found in our study (Table 5) were very close to results observed in other studies, for example for birch forests and tundra soils (mean value 62%; Turner et al. 2004) and for temperate rain forests in New Zealand (mean value 52%; Turner et al. 2007). The proportions of P org in the upper soil profile extended the range of values published for temperate European beech forest ecosystems on loess (44–55%; Talkner et al. 2009; our study: 35–83%), with the largest proportions of Porg found at the upper end of the P gradient. Also Ratios of C:Porg of the soils continuously increased with decreasing P stock (Table 5). Both observations suggest more intense usage of Porg at the P-poor sites.

Considering the classification of C:Porg ratios in Oa and A horizons used in Germany for forest site assessment (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Forsteinrichtung 1996), the site LUE is more P limited than all other sites, which had ratios in the medium (Oa) and moderately small (uppermost A horizon) range. Remarkably, C:Porg ratios of soil organic matter of the different study sites converged in subsoil horizons (Table 5). This might be due to specific C:P ratios of dissolved organic matter, which is the most important source of Porg in subsoil horizons. This is supported by a recent meta-analysis of soil organic matter stoichiometry in a large number of soils worldwide by Tipping et al. (2016). Their data analysis suggests that relatively P and N-rich organic matter is selectively sorbed by mineral surfaces.

Any intense use of soil Porg structures should alter its chemical composition. Indeed, we observed distinct changes in the quality of Porg by NMR analyses. Proportions of diester-P and phosphonate-P in organic P forms increased along the decreasing P gradient (Table 6). It has been assumed that diester-P is more readily available to microbial breakdown than monoester-P (Hinedi et al. 1988, Guggenberger et al. 1996). Large proportions of diester-P have also been observed in acid soils of other studies. The controls on the proportion of diester-P are still under debate. Diester-P enrichment has been explained by inclusion of diester-P into large organic molecules (Turner et al. 2007) or by low activity of degrading enzymes (see below).

At the P-poor sites, the proportions of phosphonate-P exceeded by far the levels reported for more fertile soils (e.g., Sumann et al. 1998). Accumulation of phosphonate-P has been observed for very acidic or water-logged conditions (Condron et al. 2005). In contrast to our observation, phosphonate-P concentrations showed extremely low concentrations at the late and P-poor states of the Franz-Josef chronosequence (Turner et al. 2007). A relative increase in phosphonate-P along the geosequence (towards LUE) could be favoured by elevated chemical stability of these compounds; particularly biogenic phosphonates were shown to resist chemical degradation (Ternan et al. 1998). Enzymes involved in the degradation of Porg can be both, regulated by the concentration of inorganic P (as part of the Pho regulon) or substrate-induced (LysR regulated). While Pho-regulated phosphonatases are primarily expressed to meet the organisms‘demand for P during phosphate starvation, the latter ones also provide C and N to cells (McGrath et al. 2013). Once easily degradable phosphoester-bonds are hydrolyzed, the more stable organophosphonates remain in the soil. In line with the NMR findings, metagenomic datasets confirmed a significantly elevated microbial potential for one type of phosphonate degrading enzyme (phosphonoacetaldehyde hydrolase) at site LUE (Bergkemper et al. 2016). Probably, the LUE microbial community has adapted to the elevated levels of organophosphonates, thus, showing a higher abundance of the respective genes.

Phosphorus mobilization

The results above mainly address the amount of P in the solid phase. Analysis of the isotopic exchange kinetics provides information on the exchangeability of P between the soil solid phase and the soil solution (Fardeau 1996) and, therefore, on the amount of inorganic P that may diffuse to the absorbing surface of roots or hyphae. The parameter n describes the rate of disappearance of the tracer from the solution after 1 min, thus, accounts for slower physical–chemical reactions (Randriamanantsoa et al. 2013). The parameter m informs on the capacity of the soil to sorb inorganic P (Randriamanantsoa et al. 2013). Small m values indicate a high sorption potential. For the set of soil samples studied, m was significantly correlated to FeCBD (which is related to the total number of sorption sites) and CP (m = 0.47 + 0.39*CP—0.016*FeCBD; r2 = 0.67, p < 0.01). The values obtained for m confirm the low sorption capacity for inorganic P of LUE, and the high P sorption capacity of the soils at the other sites. Low sorption capacity of the soils from site LUE might be explained by the low concentration of iron und aluminum oxides at this site (S6). Interestingly, water soluble P was much higher for the LUE AE horizon than for the other samples. This high value can be explained by the release of microbial P following drying before analysis and subsequent rewetting during analysis (Bünemann et al. 2013). This indicates the high relevance of the microbial pool for the storage of P at the P-poor site LUE, which is in agreement with the metagenomics and NMR data discussed above.

E1min values were in most cases equal or larger than 5 mg P kg−1, the level above which the yield of crop plants does not increase following P application (Gallet et al. 2003). This threshold was, however, found to be valid in soils that had sufficient P exchangeable on the medium term (i.e., between 1 min and 3 months) and were able to sustain significant P desorption flux into the soil solution. This was not the case at LUE. Samples from the LUE AE horizon were characterized by very little P exchangeable between 1 min and 3 months. In agreement with the results from a subsequent soil sampling at sites BBR and LUE (Bünemann et al. 2016), the results obtained here suggest that diffusion of inorganic P into the solution can sustain P availability at most sites but is probably not sufficient to cover the plant demands at LUE. Thus, beech forests at LUE strongly depend on P recycling from soil organic matter.

Response of soil organisms and trees to P stocks of soils

Microbial biomass

The Cmic:Nmic:Pmic ratios detected at the five sites (mean molar ratio: 32:2:1) were comparable to results obtained for tropical mountain forest soils (32:3:1; Tischer et al. 2014) but were lower than documented by a global forest dataset (74:9:1; Cleveland and Liptzin 2007). The Cmic:Pmic ratios were similar to those found in other beech forests (Joergensen et al. 1995). In addition, Turner and Condron (2013) observed similar Cmic:Pmic values based on the same method for Pmic analysis. The Cmic:Pmic values increased with decreasing P status of the soils.

Pools of microbial C, N and P were lowest at site LUE, indicating the general limitation of soil nutrients and the acidic conditions at this site (Table 8). In a previous study, adaptation of the microbial community to nutrient limitation at the site LUE was shown by a significant higher abundance of oligotrophic taxa such as Acidobacteriales than at BBR (Bergkemper et al. 2016). Surprisingly, Pmic reached maximum values at sites MIT and CON, although concentrations of bioavailable P (PResin) were highest at site BBR (Table 3). In contrast to the Cmic:Pmic ratio, Pmic in the mineral topsoil did not follow the P gradient of soil total P stocks (BBR > MIT ≥ VES > CON > LUE). Presumably, microbial growth in BBR is restricted by other soil nutrients or environmental conditions.

While Pmic was lowest at LUE, ratios of Cmic:Pmic, Nmic:Pmic and Cmic:Nmic were larger than at the other study sites (Table 8). The increased ratio of Cmic:Nmic indicates a higher fungal contribution to the microbial biomass at site LUE (Mouginot et al. 2014; Fierer et al. 2009). Accordingly, previous data from a metagenomics approach showed a tenfold more fungal sequences at LUE than at BBR, where also the Cmic:Nmic ratio was much larger (Bergkemper et al. 2016). The large ratio of Cmic:Pmic in LUE also indicated a strong fungal contribution to the microbial biomass (Heuck et al. 2015). The imbalance of the microbial biomass over the C:P ratio of the soil organic matter ranged from 9 to 45- It increased along the geosequence and was larger at all sites than the average global value for terrestrial ecosystems of 7 (Xu et al. 2013). These results stress the need for P-specific decomposition strategies and for high P uptake efficiency by microorganisms.

Activities of phosphomonoesterase and phosphodiesterase

Phosphatases hydrolyse different phosphate ester bonds to release inorganic P. Therefore, phosphomonoesterases cleave P from monoester forms, such as phospholipids or nucleotides, and phosphodiesterases release P from compounds like nucleic acids (Keller et al. 2012; Paul 2015). Since plants secrete phosphodiesterase only under severe P deficiency, the enzyme is mainly produced by microorganisms (Turner and Haygarth 2005). Phosphodiesterase activity showed more similar patterns among the five soil profiles than the phosphomonoseterase activity (data not shown). However, phosphodiesterase activity was much lower than phosphomonoesterase activity, as already noted by Turner and Haygarth (2005) for different pasture soils. The absolute activities of the two enzymes were consistent with the species composition of P org forms in the NMR spectra, with a range of 7–34% for diester-P and a range of 36–86% for monoester-P (Table 6). The most striking result was that the LUE site was characterized by high concentrations of diester-P (Table 6) but low phosphodiesterase activities, resulting in large ratio of phosphomonoesterase to phosphodiesterase activity (Fig. 4). This result can be explained by low enzyme production of microorganisms at this site and/or low enzyme stability at low pH values at the LUE site (Table 3; Turner and Haygarth 2005). Limited enzyme concentrations were found as a main reason for recalcitrance of phosphodiesters in different soils (Jarosch 2016). The retarded hydrolysis of diesters might cause the relative large concentrations of diester P at the LUE site. The large C:Porg ratio at the site LUE is in agreement with relative enrichment of diester compounds due to limited enzyme concentrations. Finally, retarded hydrolysis of diesters might also be the reason for the thick forest floor forming at the P-poor sites and the low turnover of organic matter (Table 4).

Leaves

According to Mellert and Göttlein (2012), the observed range of leaf P concentrations (1.2–1.7 mg g−1) are in the “normal range” of European beech. Only beech leaves at sites CON and LUE were in the concentration range of latent P deficiency, with P leaf concentrations of 1.1–1.2 mg g−1. With N:P ratios of 21 and 19 of leaves, respectively, these sites were also close to or even above the critical N:P ratio of 18.9 given for beech leaves (Talkner et al. 2015; Mellert and Göttlein 2012). The increasing difference between the P concentrations of living leaves and the P concentration of leaf litter showed an increasing P re-sorption by trees from senescing leaves with decreasing P contents of the soils. Likely, high P re-sorption is an adaptation of European beech to low P supply (Hofmann et al. 2016; Schmidt et al. 2016; Netzer et al. 2017). In summary, neither standing biomass (Table 1) nor the amount of litter produced (Table 4) seem to be related to the gradient soil P contents. However, based on leaf nutrient concentrations, the sites CON and LUE seem to approach P limitation.

Roots

We observed a strong concentration of root biomass in topsoil horizons at the P-poor sites (Fig. 3), while roots penetrated subsoils especially at P-rich sites (fine root biomass at 80 cm soil depth: BBR 38 mg m−2; LUE 2.7 mg m−2). Several studies provide evidence that low P concentrations of soils favour the growth of fine roots of different tree species (e.g., Ericsson and Ingestad 1988 for birch, Schneider et al. 2001 for oak). Less information is available on the controls of the depth distribution of the fine root biomass with high depth resolution. Despite large differences in soil P availability, the P concentrations in fine roots showed only a moderate decline with decreasing soil P (Zavišić et al. 2016). Relative differences in fine-root P concentrations at the sites were still bigger than differences in leaf concentrations (Table 4). Obviously, the P supply to roots was facilitated by mycorrhizal fungi, since all vital root tips were completely enwrapped by the fungal mantles. This is in line with observations from other P-poor sites (Schneider et al. 2001). Only in deep soil horizons, the growth of roots seemed to be P-limited, as indicated by very low P concentrations in roots (0.3 mg g−1). Very low P concentrations in coarse roots have also been observed at the P-poorest site LUE (Yang et al. 2016). This finding is well in line with those from isotope exchange kinetics, showing that particularly at site LUE there was no release of mineral-bound inorganic P into soil solution. Thus, roots are limited to the surface layers with elevated microbial activity and P mobilization from organic matter. Of the analyzed biological traits, root distribution between topsoil and subsoil compartments seemed most sensitive to the P status of soils. The ratio of P in fine roots to Pmic of the topsoil horizons (0–20 cm) tended to increase with decreasing P status of the soils (BBR: 0.05–LUE: 0.16). This suggests that beech fine roots and/or associated hyphae are more effective at maintaining P concentrations than microorganisms with decreasing P availability. However, it is not clear whether this is simply a result of more effective uptake or other mechanisms, such as uptake from the deeper subsoil.

P nutrition strategies

We defined ecosystem traits that indicate the intensity of P acquisition (acquiring indicators) and the intensity of P recycling (recycling indicators) (Table 2). We are aware that in ecosystems specific trait values might be achieved by different paths. Thus, our indicator approach provides no concluding proof for underlying mechanisms. Yet, it enables a consistency test for the supply-controlled nutrition strategies of beech forest ecosystems. The indicator values allow for relating nutrition strategies in a quantitative way to the P stocks of soils, thereby providing novel information on how the adjustment of nutrition strategies to changes in P stocks of forest soils occurs.

We assume that ecosystems with P acquiring strategies are characterised by spatial (Jobbágy and Jackson 2004) and chemical (Prietzel et al. 2016) redistribution of P in soils, for example through P uptake in deeper horizons and fixation of the P mobilized during litter decay by topsoil minerals. Based on this assumption, we identified the following acquiring indicators: (1) P enrichment in topsoil horizons, (2) share of non-stable P in the profile, and (3) kinetics of phosphate mobilization (Table 2).

All the three acquiring indicators highlight more intense spatial and chemical redistribution of P in P-rich than in P-poor soils. We generally observed larger P concentrations in topsoil layers than in subsoil layers (Fig. 1). Published data on P in temperate forest soils confirm this observation (e.g., Talkner et al. 2009; Jobbágy and Jackson 2004). At our study sites, the differences between topsoil and subsoil concentrations were more pronounced at P-rich than at P-poor sites. At sites with large mineral P concentrations, the C investment for establishing and maintaining a deep root system might pay off through gains in nutrient uptake. At P-poor sites, these costs are too high given the low amount of P in the subsoil horizons. The actual depth distribution of fine-root biomass is in line with this explanation, although this does not exclude the possibility that at least some roots also acquire P from deeper depths at P-poor sites. The depth distribution of Porg obtained from Hedley fractionation additionally suggests increased P acquisition from subsoil material at P-rich sites. The proportion of Porg in the subsoil horizons is higher at P-rich than at P-poor sites (supplementary material S7), which might reflect intense root foraging for P and fine-root turnover in the subsoil horizons of P-rich sites (Cross and Schlesinger 1995). Hedley fractionation results indicate that intense P acquisition occurs preferentially at P-rich sites: In general, the proportion of residual P seems to be greater at sites low in P than at those having large P stocks (supplementary material S7, see above). This observation corresponds to the P speciation of soil samples by XANES by Prietzel et al. (2016). They observed that P speciation in soils from 10 different forest sites in Germany is strongly related to P cycling in these soils. However, the increasing proportion of stable P with decreasing P stocks might also be explained by increasing fixation of organic and inorganic P by mineral sorbents (Velásquez et al. 2016). Yet the P-poorest site LUE is characterized by low contents of Fe and Al oxyhydroxides. Thus, fixation by mineral sorbents should be of lower relevance than at the other sites. Mobilization kinetics has often been assumed to indicate plant availability, and P mobilization determined by isotopic exchange has been shown to be closely related to plant uptake (Achat et al. 2016). In line with this, P exchangeable within one day from topsoil material was closely related to the P status of the study sites. The rate of P mobilization might be both, the reason for, but also the consequence of P acquisition from mineral material.

The four recycling indicators identified were remarkably closely related to the P stocks of the different geosequence sites: (1) accumulation of P in the forest floor (r2 0.94) (2) fine-root biomass accumulation in the forest floor (r2 0.95), (3) residence time of the forest floor (r2 0.99), and (4) contribution of diester-P to total P in A horizons (r2 0.89; Fig. 3). Also, all the four recycling indicators averaged in the normalized form for aggregated illustration (Fig. 5) confirm decreasing intensity of P recycling with increasing P supply (r2 0.96, p < 0.01, for the linear regression of recycling indicator values vs. P soil stocks). Thus, most of P seemingly is contained in the surface organic-rich layers at P-poor sites. Slow turnover and high rooting intensity may foster tight P recycling (Fig. 3). Beyond that, we observed an unexpected close, linear, and positive correlation between the diester-P/monoester-P ratio of mineral topsoil horizons and the P stock at a given site (Fig. 3). Despite the uncertainties in the interpretation of NMR data mentioned above, some authors suggested the diester-P/monoester-P ratio as indicator of microbial P transformation (e.g., Turrión et al. 2000). The increase in the diester-P/monoester-P ratio can be seen as a biomarker pointing at increased microbial recycling of organic P with increasing deficiency in overall P supply. This supports our hypothesis that there is a shift to P recycling systems in forest surface soils under extreme P limitations. High phosphomonoesterase-to-diesterase ratios at site LUE likely maintain those chemical signatures.

Means of normalized indicator values as calculated according to Eq. (3) for the different sites. Bars represent the standard error of normalized values

In summary, the indicator values obtained confirm that European beech forests at silicate sites are characterized by different P nutrition strategies, depending on the P stocks of the soils. Our results imply that with decreasing P contents by the mineral soil, the intensity of recycling processes increases continuously whereas the intensity of acquisition processes decreases. Future work needs to analyze how these different strategies might be impacted by perturbations or disturbances, such as chronic N deposition or climatic extremes. Our results support ideas, which help exemplify the use of such indicators: Interestingly, the peak of biological activity along the P gradient does not seem to be at site BBR (highest P stock) but at sites MIT and VES (intermediate P stocks). These two sites showed the highest P leaf concentrations (Table 4), the lowest Cmic:Pmic values (Table 8), the largest ratio of Porg to total P, and the highest C stocks in soils (Table 3) among the study sites. Under intermediate conditions, P nutrition of vegetation and microbes might be best owing to a mixture of recycling and acquisition strategies.

Ecosystem properties responding to P nutrition strategies

As a consequence of the close relationship between P contents and P recycling indicators, as well as of the small variation of P leave concentrations, intense P recycling seems to improve the P use efficiency of P-poor beech forest ecosystems (Fig. 6). The correlation indicates that tight recycling resulting from “well-adjusted” P mobilisation and P uptake by different organisms, thus, also improves the P supply for trees. This, in turn, implies that plant and microbial communities as a whole are adapted to specific environmental conditions, and confirms the concept of ecosystem nutrition (Lang et al. 2016). The results stress that also other ecosystem properties not directly related to P are interacting with P nutrition strategies. Tight cycling appears to be linked to intense P mineralisation, root growth, and P uptake in the forest floor. Particularly, the establishment of the forest floor tightens P cycling and acts as kind of “funnel” to provide available P where required. The formation of the forest floor, in turn, could be facilitated by the depletion in P of the soil organic matter and the P limitation of those organisms inducing depolymerisation of diester-P molecules in the mineral soil. Also, anthropogenic impacts on forest soils, as for example increased N input or climate change and increasing temperatures will affect these interactions and might, thus, disturb the P nutrition strategies of P-poor ecosystems.

Conclusion

We selected a novel P geosequence approach on silicate material to unravel the response of European beech forests to different soil P stocks. Our results are in line with the hypothesis of a tightening of P cycles with decreasing soil P availability and they provide evidence for the existence of adaptation processes at the ecosystem level. In P-rich but acid soils, plants and soil organisms mobilize P from primary and secondary minerals. In P-poor soils, roots and fungi seem to sustain their P demand more successfully than bacteria, mainly from the forest floor and soil horizons rich in organic matter. In turn, this influences the quality of organic P compounds in soils, which underwent pronounced changes along the P geosequence. Our indicators for P recycling and P acquisition pointed at a continuous change in nutrition strategies with changing P supply. However, elevated proportions of organic P, smallest C:P ratios in microbial biomass, and largest P concentrations in beech leaves were observed at sites of intermediate P stocks, where the combination of different nutrition strategies might favor P uptake. Overall, our results thus underline the high adaptability of beech forest ecosystems to changing P supply. We conclude that within the range of P stocks analyzed, P deficiency in beech forest ecosystems is unlikely the result of a low P supply per se. More likely, sufficient P nutrition depends on supply-specific plant–microorganism–soil interactions.

References

Achat DL, Pousse N, Nicolas M, Brédoire F, Augusto L (2016) Soil properties controlling inorganic phosphorus availability. General results from a national forest network and a global compilation of the literature. Biogeochemistry 127(2–3):255–272. doi:10.1007/s10533-015-0178-0

Ad hoc-Arbeitsgruppe Boden (2005) Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung. Ed.: Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe in Zusammenarbeit mit den Staatlichen Geologischen Diensten. 5th edition. Hannover. ISBN 3-510-95920-5

Augusto L, Achat DL, Jonard M, VidalD Ringeval B (2017) Soil parent material—a major driver of plant nutrient limitations in terrestrial ecosystems. Glob Change Biol. doi:10.1111/gcb.13691

Amelung W, Rodionov A, Urusevskaja I, Haumaier L, Zech W (2001) Forms of organic phosphorus in zonal steppe soils of Russia assessed by 31P NMR. Geoderma 103(3–4):335–350. doi:10.1016/S0016-7061(01)00047-7

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Forsteinrichtung (1996) Forstliche Standortsaufnahme. Begriffe, Definitionen, Einteilungen, Kennzeichnungen, Erläuterungen, 5. Aufl. IHW-Verl., Eching bei München

Backnäs S, Laine-Kaulio H, Kløve B (2012) Phosphorus forms and related soil chemistry in preferential flowpaths and the soil matrix of a forested podzolic till soil profile. Geoderma 189–190:50–64. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.04.016

Bergkemper F, Schöler A, Engel M, Lang F, Krüger J, Schloter M, Schulz S (2016) Phosphorus depletion in forest soils shapes bacterial communities towards phosphorus recycling systems. Environ Microbiol 18(6):1988–2000. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13188

Bol R, Amelung W, Haumaier L (2006) Phosphorus-31–nuclear magnetic–resonance spectroscopy to trace organic dung phosphorus in a temperate grassland soil. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 169(1):69–75. doi:10.1002/jpln.200521771

Bol R, Julich D, Brödlin D, Siemens J, Kaiser K, Dippold MA, Spielvogel S, Zilla T, Mewes D, von Blanckenburg F, Puhlmann H, Holzmann S, Weiler M, Amelung W, Lang F, Kuzyakov Y, Feger K, Gottselig N, Klumpp E, Missong A, Winkelmann C, Uhlig D, Sohrt J, von Wilpert K, Wu B, Hagedorn F (2016) Dissolved and colloidal phosphorus fluxes in forest ecosystems-an almost blind spot in ecosystem research. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. doi:10.1002/jpln.201600079

Brankatschk R, Töwe S, Kleineidam K, Schloter M, Zeyer J (2011) Abundances and potential activities of nitrogen cycling microbial communities along a chronosequence of a glacier forefield. ISME J 5(6):1025–1037. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.184

Brookes PC, Powlson DS, Jenkinson DS (1982) Measurement of microbial biomass phosphorus in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 14(4):319–329. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(82)90001-3

Bünemann EK, Augstburger S, Frossard E (2016) Dominance of either physicochemical or biological phosphorus cycling processes in temperate forest soils of contrasting phosphate availability. Soil Biol Biochem 101:85–95. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.07.005

Bünemann EK, Keller B, Hoop D, Jud K, Boivin P, Frossard E (2013) Increased availability of phosphorus after drying and rewetting of a grassland soil. Processes and plant use. Plant Soil 370(1–2):511–526. doi:10.1007/s11104-013-1651-y

Cade-Menun BJ (2005) Characterizing phosphorus in environmental and agricultural samples by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Talanta 66(2):359–371. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2004.12.024

Cade-Menun BJ (2015) Improved peak identification in 31P-NMR spectra of environmental samples with a standardized method and peak library. Geoderma 257–258:102–114. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.12.016

Celi L, Cerli C, Turner BL, Santoni S, Bonifacio E (2013) Biogeochemical cycling of soil phosphorus during natural revegetation of Pinus sylvestris on disused sand quarries in Northwestern Russia. Plant Soil 367(1–2):121–134. doi:10.1007/s11104-013-1627-y

Chen CR, Hou EQ, Condron LM, Bacon G, Esfandbod M, Olley J, Turner BL (2015) Soil phosphorus fractionation and nutrient dynamics along the Cooloola coastal dune chronosequence, southern Queensland, Australia. Geoderma 257–258:4–13. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.04.027

Cleveland CC, Liptzin D (2007) C. N: p stoichiometry in soil: is there a “Redfield ratio” for the microbial biomass? Biogeochemistry 85(3):235–252. doi:10.1007/s10533-007-9132-0

Condron LM, Turner BL, Cade-Menun BJ, Sims JT, Sharpley AN (2005) Chemistry and dynamics of soil organic phosphorus. Phosphorus 87–121

Cross A, Schlesinger W (1995) A literature review and evaluation of the Hedley fractionation: applications to the biogeochemical cycle of soil phosphorus in natural ecosystems. Geoderma 64:197–214. doi:10.1016/0016-7061(94)00023-4

Crouse DA, Sierzputowska-Gracz H, Mikkelsen RL (2000) Optimization of sample ph and temperature for phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of poultry manure extracts. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 31(1–2):229–240. doi:10.1080/00103620009370432

de Vries W, Reinds G, Vel E (2003) Intensive monitoring of forest ecosystems in Europe. For Ecol Manage 174(1–3):97–115. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00030-0

Eberle J, Allgaier B (2010) Deutschlands Süden vom Erdmittelalter zur Gegenwart, 2. Aufl. Spektrum-Sachbuch. Spektrum Akad. Verl., Heidelberg, Neckar

Ergenzinger P (1967) Die eiszeitliche Vergletscherung des Bayerischen Waldes. Einzeitalter & Gegenwart 18(1):152–168

Ericsson T, Ingestad T (1988) Nutrient and growth of birch seedlings at varied relative phosphorus addition rates. Plant Physiol 72:227–235. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1988.tb05827.x

Fardeau JC (1993) Available soil phosphate: its representation by a functional multiple compartment model [conceptual model, pool, buffering capacity]. Agronomie 13:317–331

Fardeau JC (1996) Dynamics of phosphate in soils. An isotopic outlook. Fertil Res 45:91–100

Fiebig M, Ellwanger D, Doppler G (2011) Pleistocene glaciations of Southern Germany. In: Ehlers J, Gibbard PL, Hughes PD (eds) Quaternary glaciations- extent and chronology: a closer look, vol 15. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 163–173

Fierer N, Strickland MS, Liptzin D, Bradford MA, Cleveland CC (2009) Global patterns in belowground communities. Ecol Lett 12(11):1238–1249. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01360.x

Gallet A, Flisch R, Ryser J, Frossard E, Sinaj S (2003) Effect of phosphate fertilization on crop yield and soil phosphorus status. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 166(5):568–578. doi:10.1002/jpln.200321081

Galván-Tejada NC, Peña-Ramírez V, Mora-Palomino L, Siebe C (2014) Soil P fractions in a volcanic soil chronosequence of Central Mexico and their relationship to foliar P in pine trees. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 177(5):792–802. doi:10.1002/jpln.201300653

Gerke J, Hermann R (1992) Adsorption of orthophosphate to humic-Fe-complexes and to amorphous Fe-oxide. Z Pflanzenernaehr. Bodenk 155(3):233–236. doi:10.1002/jpln.19921550313

Geyer OF, Gwinner MP (1986) Geologie von Baden-Württemberg. Mit 26 Tab, 3., völlig neubearb. Aufl. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart

Guckland A, Jacob M, Flessa H, Thomas FM, Leuschner C (2009) Acidity, nutrient stocks, and organic-matter content in soils of a temperate deciduous forest with different abundance of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 172(4):500–511. doi:10.1002/jpln.200800072

Guggenberger G, Haumaier L, Zech W, Thomas RJ (1996) Assessing the organic phosphorus status of an Oxisol under tropical pastures following native savanna using 31P NMR spectroscopy. Biol Fertil Soils 23(3):332–339. doi:10.1007/BF00335963

Haas J, Hagge Ellhöft K, Schack-Kirchner H, Lang F (2016) Using photogrammetry to assess rutting caused by a forwarder—A comparison of different tires and bogie tracks. Soil Tillage Res 163:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.still.2016.04.008

Hamburg SP (1984) Effects of forest growth on soil nitrogen and organic matter pools following release from subsistence agriculture. In: Stone EL (ed) Forest soils and treatment impacts. Univiversity of Tennessee, Knoxville, pp 145–158

Hayes JE, Richardson AE, Simpson RJ (2000) Components of organic phosphorus in soil extracts that are hydrolysed by phytase and acid phosphatase. Biol Fertil Soils 32(4):279–286. doi:10.1007/s003740000249

Hedley MJ, Stewart J (1982) Method to measure microbial phosphate in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 14(4):377–385. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(82)90009-8

Hendershot WH, Lalande H, Duquette M (2008) Ion exchange andexchangeable cations. In: Carter MR, Gregorich EG (eds) Soil sampling and methods of analysis, vol 2. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 197–206

Heuck C, Weig A, Spohn M (2015) Soil microbial biomass C. N: P stoichiometry and microbial use of organic phosphorus. Soil Biol Biochem 85:119–129. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.02.029

Hinedi ZR, Chang AC, Lee RWK (1988) Mineralization of phosphorus in sludge-amended Soils monitored by phosphorus-31-nuclear magnetic resonance Spectroscopy. Soil Sci Soc Am J 52(6):1593. doi:10.2136/sssaj1988.03615995005200060014x

Hoffmann G (1968) Eine photometrische Methode zur Bestimmung der Phosphatase-Aktivität in Böden. Z. Pflanzenernaehr. Bodenk 118(3):161–172. doi:10.1002/jpln.19681180303

Hofmann K, Heuck C, Spohn M (2016) Phosphorus resorption by young beech trees and soil phosphatase activity as dependent on phosphorus availability. Oecologia 181(2):369–379. doi:10.1007/s00442-016-3581-x

Jarosch KA (2016) New approaches to characterise soil organic phosphorus and to measure phosphorus transformation rates. Dissertation, ETH

Jobbágy EG, Jackson RB (2004) The uplift of soil nutrients by plants. Biogeochemical consequences across scales. Ecology 85(9):2380–2389. doi:10.1890/03-0245

Joergensen RG (1996) The fumigation-extraction method to estimate soil microbial biomass. Calibration of the kEC value. Soil Biol Biochem 28(1):25–31. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(95)00102-6

Joergensen RG, Kübler H, Meyer B, Wolters V (1995) Microbial biomass phosphorus in soils of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests. Biol Fertil Soils 19(2–3):215–219. doi:10.1007/BF00336162

Joergensen RG, Mueller T (1996) The fumigation-extraction method to estimate soil microbial biomass. Calibration of the kEN value. Soil Biol Biochem 28(1):33–37. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(95)00101-8

John MK (1970) Colorimetric determination of phosphorus in soil and plant materials with ascorbic acid. Soil Sci 109(4):214–220

Jonard M, Fürst A, Verstraeten A, Thimonier A, Timmermann V, Potočić N, Waldner P, Benham S, Hansen K, Merilä P, Ponette Q, de la Cruz AC, Roskams P, Nicolas M, Croisé L, Ingerslev M, Matteucci G, Decinti B, Bascietto M, Rautio P (2015) Tree mineral nutrition is deteriorating in Europe. Glob Chang Biol 21:418–430

Keller M, Oberson A, Annaheim KE, Tamburini F, Mäder P, Mayer J, Frossard E, Bünemann EK (2012) Phosphorus forms and enzymatic hydrolyzability of organic phosphorus in soils after 30 years of organic and conventional farming. Z Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk 175(3):385–393. doi:10.1002/jpln.201100177

Kelly EF, Chadwick OA, Hilinski TE (1998) The effect of plants on mineral weathering. In: van Breemen N (ed) Plant-induced soil changes: processes and feedbacks. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 21–53

Laliberté E, Grace JB, Huston MA, Lambers H, Teste FP, Turner BL, Wardle DA (2013) How does pedogenesis drive plant diversity? Trends Ecol Evol 28(6):331–340. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2013.02.008

Lang F, Bauhus J, Frossard E, George E, Kaiser K, Kaupenjohann M, Krüger J, Matzner E, Polle A, Prietzel J, Rennenberg H, Wellbrock N (2016) Phosphorus in forest ecosystems: New insights from an ecosystem nutrition perspective. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 179:129–135

Lorenz M (1995) International co-operative programme on assessment and monitoring of air pollution effects on forests-ICP forests-. Water Air Soil Pollut 85(3):1221–1226. doi:10.1007/BF00477148

Lundström U, van Breemen N, Bain D (2000) The podzolization process. A review. Geoderma 94(2–4):91–107. doi:10.1016/S0016-7061(99)00036-1

Margesin R (1996) Phosphodiesterase activity. In: Schinner F, Öhlinger R, Kandeler E, Margesin R (eds) Methods in soil biology. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 217–219

Marschner P, Hatam Z, Cavagnaro TR (2015) Soil respiration, microbial biomass and nutrient availability after the second amendment are influenced by legacy effects of prior residue addition. Soil Biol Biochem 88:169–177. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.023

McGrath JW, Chin JP, Quinn JP (2013) Organophosphonates revealed: new insights into the microbial metabolism of ancient molecules. Nature reviews. Microbiology 11(6):412–419. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3011

Mehra OP, Jackson ML (1960) Iron oxide removal from soils and clay by a dithionite-citrate system buffered with sodium bicarbonate. Clays Clay Miner 7:317–327

Mellert KH, Göttlein A (2012) Comparison of new foliar nutrient thresholds derived from van den Burg’s literature compilation with established central European references. Eur J For Res 131(5):1461–1472. doi:10.1007/s10342-012-0615-8

Mooshammer M, Wanek W, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Richter A (2014) Stoichiometric imbalances between terrestrial decomposer communities and their resources: mechanisms and implications of microbial adaptations to their resources. Front Microbiol 5:22. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00022

Mouginot C, Kawamura R, Matulich KL, Berlemont R, Allison SD, Amend AS, Martiny AC (2014) Elemental stoichiometry of Fungi and Bacteria strains from grassland leaf litter. Soil Biol Biochem 76:278–285. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.05.011

Murphy J, Riley JP (1962) A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica chimica acta 27:31–36

Netzer F, Schmid C, Herschbach C, Rennenberg H (2017) Phosphorus-nutrition of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) during annual growth depends on tree age and P-availability in the soil. Environ Exp Botany 137:194–207. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.02.009

Odum EP (1969) The strategy of ecosystem development. Science 164(3877):262–270. doi:10.1126/science.164.3877.262

Oehl F, Oberson A, Sinaj S, Frossard E (2001) Organic phosphorus mineralization studies using isotopic dilution techniques. Soil Sci Soc Am J 65(3):780. doi:10.2136/sssaj2001.653780x

Öhlinger R (1996) Phosphomonoesterase activity with the substrate phenylphosphate. In: Schinner F, Öhlinger R, Kandeler E, Margesin R (eds) Methods in Soil Biology. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 210–213

Ohno T, Zibilske LM (1991) Determination of low concentrations of phosphorus in soil extracts using malachite green. Soil Sci Soc Am J 55(3):892. doi:10.2136/sssaj1991.03615995005500030046x

Paul EA (ed) (2015) Soil microbiology, ecology and biochemistry, 4th edn. Elsevier; Academic Press, Amsterdam, London

Pearson HL, Vitousek PM (2002) Soil phosphorus fractions and symbiotic nitrogen fixation across a substrate-age gradient in Hawaii. Ecosystems 5(6):587–596

Peters R (1997) Beech forests, vol 24. Geobotany. Springer, Netherlands

Pitman R, Bastrup-Birk A, Breda N, Rautio P (2010) Sampling and Analysis of Litterfall. In: Manual on methods and criteria for harmonized sampling, assessment, monitoring and analysis of the effects of air pollution on forests, Part XIII, pp 1–16

Porder S, Ramachandran S (2013) The phosphorus concentration of common rocks—a potential driver of ecosystem P status. Plant Soil 367(1–2):41–55. doi:10.1007/s11104-012-1490-2

Prietzel J, Klysubun W, Werner F (2016) Speciation of phosphorus in temperate zone forest soils as assessed by combined wet-chemical fractionation and XANES spectroscopy. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 179(2):168–185. doi:10.1002/jpln.201500472

Randriamanantsoa L, Morel C, Rabeharisoa L, Douzet J, Jansa J, Frossard E (2013) Can the isotopic exchange kinetic method be used in soils with a very low water extractable phosphate content and a high sorbing capacity for phosphate ions? Geoderma 200–201:120–129. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.01.019