Abstract

Purpose

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has caused unprecedented challenges for surgical staffs to minimize exposure to COVID-19 or save medical resources without harmful patient outcomes, in accordance with the statement of each surgical society. No research has empirically validated declines in surgical volume in Japan, based on the usage of surgical triage. We aimed to identify whether the announcement of surgical priorities by each Japanese surgical society may have affected the surgical volume decline during the 1st wave of this pandemic.

Methods

We extracted 490,719 available cases of patients aged > 15 years who underwent elective major surgeries between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020. After the categorization of surgical specialities, we calculated descriptive statistics to compare the year-over-year trend and conducted an interrupted time series analysis to validate the decline of each surgical procedure.

Results

Monthly surgical cases of eight surgical specialities, especially ophthalmology and ear/nose/throat surgeries, decreased from April 2020 and reached a minimum in May 2020. An interrupted time series analysis showed no significant trends in oncological and critical surgeries.

Conclusion

Non-critical surgeries showed obvious and statistically significant declines in case volume during the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic according to the statement of each surgical society in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which first appeared in Wuhan, China, has been increasing and disrupting healthcare systems worldwide [1]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, surgical staffs have experienced unprecedented challenges [2,3,4]. To minimize exposure to COVID-19 and save medical resources to prevent harmful outcomes for the patients, cancellation or triage of surgeries are recommended [3,4,5]. Patients with critical diseases and cancers should still receive surgery as usual; whereas, cases with benign diseases can be postponed [6,7,8].

Previous studies suggest that there are wide variations in the trends of the affected number of surgical procedures depending on the country and time period [3, 4, 9]. The Japanese Surgical Society (JSS, which consists of ten major surgical societies in Japan) announced the importance of triage by case severity and surgical recovery planning for the backlog of surgeries [10]. A comprehensive surgical and medical care strategy is also recommended to prevent potential adverse health implications caused by surgical delays [11].

However, there are no studies validating the trends of surgeries based on the announcement of surgical triage during the 1st wave of this pandemic in Japan, one of the regions most affected by COVID-19 at the earliest stage throughout the world. In this report, we performed a retrospective cohort study discussing the impact of the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on major elective surgical procedures in Japan, referring to the priorities announced by each surgical society in Japan.

Methods

Data source

We used the Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) data from the Quality Indicator/Improvement Project (QIP) database, the program administered by the Department of Healthcare Economics and Quality Management, Kyoto University.

The DPC/per-diem payment system (PDPS) is a Japanese prospective payment system applied to acute care hospitals that is comparable to diagnosis-related databases in the United States [12, 13]. A total of 1730 hospitals adopted the DPC/PDPS in 2018, accounting for 54% of all general beds in Japanese hospitals [14, 15]. DPC data do not include information on laboratory findings and reasons for surgery; instead, they provide information included in the discharge summary, such as the primary diagnosis, comorbidities [identified by using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes], type of surgery, and codes corresponding to the medical procedures performed.

Study population

Among the QIP hospitals, the eligibility criteria for inclusion in this study were as follows: age > 15 years and having had selective surgical procedures during hospitalization between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020. We did not exclude any patients.

Variables and surgical procedure

Regarding the patients’ background characteristics, we referred to their sex, age, and length of stay (LOS), as well as the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices [16]. We also identified and categorized the surgical speciality from the main surgery during admission based on previous reports [5, 9]: oncological, abdominal, genitourinary, cardiovascular, neurosurgery, orthopedic, ophthalmology, and ear/nose/throat (ENT). Except for oncological surgeries, owing to the wide variety of surgical procedures, we included the top three most common surgeries in Japan based on the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB), which covers the medical claim information of the entire Japanese population of 127 million [17]. Details on the surgical classification are shown by K codes, which are the claims codes for surgery, in Supplemental Table 1.

Statistics

The monthly case volumes of our total eligible surgeries are presented in Fig. 1, using line graphs. The monthly cases by surgical speciality between July 2018 and June 2020 are also shown in Table 1 to compare the reduction.

We used ITS, including segmented regressions, to ascertain any volume changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic on population-level admissions. We statistically evaluated the changes in the volume of surgeries based on the date of admission adjusted for seasonality through a Fourier term [18]. We hypothesize that COVID-19 would have affected the number of scheduled admissions especially after April 2020 as an implemented point, in which the Japanese Society of Anesthesiologists and the JSS requested surgeons to triage some elective surgeries. We divided our datasets into two periods for ITS analysis: before the JSS surgical-triage-statement (July 2018–March 2020) and after that (April–June 2020). Monthly case volumes of scheduled admission with surgery are presented in Fig. 1 using line graphs. Baseline demographics for the population for ITS analysis are listed in Supplemental Tables 2–9. Age was expressed as the mean ± SD and LOS as the median (interquartile range), which were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using χ2 tests. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed) in Table 2. Statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.0.2 software program (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School, Kyoto, Japan (R0135). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human participants issued by the Japanese National Government. The data were anonymized, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Results

Overview of all surgical specialities

We detected 258 hospitals and 490,719 cases of patients over 15-years-old with surgery between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020. Figure 1 displays the trend of total surgical cases per month. The case volume decreased from April and reached a minimum in May (n = 12,501). Compared to the previous year, every type of surgical volume, especially ophthalmologic and ENT surgeries, also indicated the smallest number of cases in May.

Oncological surgery

Although prior year comparisons of all oncological surgeries showed a decline since April (Supplemental Fig. 1), the ITS analysis showed no significance in the surgical volume according to the p value of > 0.05 (Fig. 2).

Abdominal, genitourinary, and cardiovascular surgery

Prior year comparisons of all abdominal, genitourinary, and cardiovascular surgeries showed a decrease from April, especially for hernia and lower-limb varices surgeries (Supplemental Figs. 2–4). An ITS analysis showed p < 0.05 in abdominal, stone, and lower-limb varices surgeries (Fig. 2: cholecystectomy p = 0.012; hernia p = 0.002; intestinal surgery p = 0.022; stone surgery p < 0.001; lower-limb varices surgery p < 0.001).

Neuro and orthopedic surgery

All surgeries except discectomy had low numbers compared to the previous year from April, particularly in May (Supplemental Figs. 5 and 6: spine fusion 68.5%; discectomy 63.3%; intracranial 49.7%; ORIF 49.3%; arthroplasty 70.1%; removal of nail 35.4%). ITS analysis of intracranial surgery and all orthopedic surgeries showed significant decline with p < 0.05 (Fig. 2; intracranial p = 0.002; ORIF p = 0.03; Arthroplasty p = 0.016; removal of nail p = 0.016).

Ophthalmologic and ear/nose/throat surgery

Supplemental Figs. 7 and 8 show a dramatic decrease in both types of surgical specialities in May (cataract 49.3%; vitreous 70.1%; blepharoplasty 35.4%; tonsillectomy 21.3%; ESS 14.4%; tympanoplasty 40.9%). The number of both types of surgeries declined because of COVID-19 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our study showed the trends of scheduled admission with surgery and important changes in surgical volume during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the announcement of the surgical triage recommendation in Japan. We found that oncological surgeries and some critical surgeries had continued according to the ITS analysis during the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, even though the year-over-year trend showed a decline.

The decline of oncological surgeries for gastrointestinal, hepato-pancreato-biliary, lung, breast, and genitourinary cancer was not significant in the ITS analysis, even though there were reductions in comparison to the same period of the previous year. For patients who had nonfatal diseases or did not require urgent medical intervention, JSS recommended postponement or performing surgery cautiously under appropriate infection control measures [5]. Owing to the risk of cancer-progression, prioritization of procedures should consider available evidence on time of surgery and oncologic outcomes [9, 19, 20]. The American College of Surgeons also recommended that surgery for low-risk cancer should be deferred but should not be postponed for most other cancers [21]. For example, our result for gastrointestinal cancer could reflect the recommendation because we did not include endoscopic procedures, which were usually performed for early-stage cancer outside the operating room. However, our result for prostate cancer showed no downward trend, which was opposite to urological triage recommendations [22]. This was probably because of the relative affordability of hospital beds recruited in this study and the patients’ wishes to perform the surgery as scheduled.

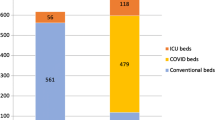

In terms of the abdominal, genitourinary, and cardiovascular surgeries, all but gynecological, aortic, and dialysis-fistula surgeries decreased with p < 0.05 in ITS analysis. Selected abdominal and stone surgery have a low priority and are basically recommended to be delayed [5, 9, 22]. Regarding gynecological surgery, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology did not established a system for surgical triage. The most common diseases for hysterectomy and adnexal surgery are uterine fibroids and ovarian cysts. Because these diseases could possibly lead to extreme anemia or torsion if left untreated, selected gynecological surgeries may have been performed with some priority [23]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, management of ICU beds and ventilators is important. There is also concern about a remarkable reduction in blood donation because many cardiovascular surgeries require perioperative transfusion [24, 25]. Considering the risk of COVID-19 infection and conservation of medical resources, certain surgical restrictions such as delaying of surgery for stable patients or transferring a patient to near-by hospitals are recommended for cardiac and aortic surgery by the Japanese Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, as in Western countries [26,27,28]. However, cardiovascular surgery is thought to be essential because of the risk of worsening or even death caused by surgical delay. For example, progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic (typically chest pain or shortness of breath) with an aortic aneurysm can increase the risk of surgery, or even worse, make surgery impossible. Similarly, if the appropriate timing of surgery for dialysis fistula is missed, a patient’s condition will become irreversible because of kidney failure. When medical resources, such as hospital beds, staff, and ventilators can be afforded to a certain extent, many cardiovascular surgeries should not be unnecessarily postponed, and such a trend was also observed in this study.

Within neurosurgery and orthopedic surgeries, every procedure declined compared to the same period in the previous year with p < 0.05, except for spinal surgeries including spinal fusion and discectomy. According to a report by Johns Hopkins University, the decrease in cranial surgery cases was largest in the department of neurosurgery [29]. Triage of elective neurosurgery was basically judged based on the symptoms, such as any signs of life-, limb- or vision-threatening conditions [30]. The Japan Neurosurgical Society also announced similar statements with only an additional alert about endoscopic surgery [31]. In this research, we chose surgeries for brain tumor, intracranial hemorrhage, and intracranial vascular as cranial surgery based on their popularity in the NDB. Because patients who underwent these surgeries after scheduled admission might possibly have had trivial symptoms, our results could have been affected by such selection effects. Spine surgery also decreased, although the ITS analysis was not significant. The Japan Neurosurgical Society announced that spine surgery is intermediate or high priority according to the symptoms [31]. Patients with a spinal injury often experience paralysis, which leads to a decline in activities of daily living (ADL) or quality of life, and the complaints of symptoms had possibly become more pronounced, which might have led to our results. Traumatic surgery is one that requires minimizing pre-operative delay and LOS despite a patient’s COVID-19 status at each hospital [9], although whether surgery is performed with optimal timing or not should be decided in each hospital based on restrictions on elective resources and procedures [32]. Considering the necessity of traumatic surgery such as for fracture, surgical volume might have declined because of the state of emergency declared by the government that led to people voluntarily refraining from going out. Arthroplasty was sometimes performed for fracture patients, although most of them were for the treatment of osteoarthritis. This might be because we selected only scheduled admission patients. Osteoarthritis adversely impacts ADL regardless of there being a state of emergency, which could be related to our results.

Finally, surgeries associated with quality of life including ophthalmologic and ENT surgeries were focused on. The Japanese Ophthalmological Society and Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society of Japan recommended cancellation or postponement of most elective surgeries because of the high probability of the COVID-19 virus being present in the nasal cavity, pharynx, and lacrimal fluid [33, 34]. Moreover, both ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists are a high-risk category of COVID-19 infection because their high daily outpatient and emergent patient volumes. In our study, the reason for the dramatic decrease in the surgical volume in otolaryngology and ophthalmology compared to other surgical categories might be that patients themselves were reluctant to be seen and that physicians in these two departments were strictly triaged by urgency.

This report focuses on the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was the most disruptive for clinical practice. Because most of the backlogged surgeries tended to have a low-priority, shifting the patients to ambulatory surgery centers or hospitals with no hospitalized COVID-19 positive patients in the same medical area may be one solution. Since the second wave, the number of scheduled surgeries has been gradually recovering, partly because the healthcare system has been more organized. However, it is still unlikely that there will be a full recovery compared to pre-pandemic levels, or even an increase in the number of surgeries to deal with the backlogged surgeries. The decrease in the number of surgeries can be attributed to various factors such as a decrease in the number of affected patients, patients refraining from pursuing medical care, and delays in surgeries. Therefore, it is important to examine what kind of surgery leads to quick recovery.

Our study is associated with several limitations. First, our target hospitals included 254 QIP participants who voluntarily provided DPC data. This study population may not have been comprehensive enough to be representative of the current situation in Japan because there are more than 8000 hospitals in Japan. In this study, participant hospitals had a variety of backgrounds, such as private, public, and teaching hospitals. COVID-19-positive patients were admitted in at least about half of the hospitals. We believe that the selection bias associated with this study was not very significant, and this result was important for understanding the future course of the pandemic. Second, we did not consider whether there was a trend for surgery originally performed in an inpatient setting for ambulatory surgery because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that some inpatient surgeries should be shifted to ambulatory surgery when possible and it is safe to do so, and the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association also cited the recommendation because of the risk of infection for medical staff and patients and the efficiency of medical resources [35]. Ambulatory surgery centers need to be prepared for the possibility of performing surgeries such as trauma and backlog surgeries that have never been experienced before depending on how the COVID-19 pandemic develops in the future.

In conclusion, we herein demonstrated and validated the trend of surgical volume reduction in Japan based on the surgical triage announced by each surgical society by applying ITS analyses. Almost all surgeries, except for oncological and critical procedures, tended to be significantly affected by COVID-19. Even in an emergency like this pandemic, the fact that surgical triage was performed in accordance with the statement suggests that medical care was provided efficiently in Japan. Future research should examine how hospitals recovered efficiently from the backlog of surgeries to prepare for the next possible pandemic wave.

References

Banerjee A, Pasea L, Harris S, Gonzalez-Izqueirdo A, Torralbo A, Shallcross L, et al. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1715–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0.

Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034.

COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020;107:140–9.

Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, Schnitzbauer AA, Line PD, Lai PB, et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11670 (published online ahead of print, 30 Apr 2020).

Mori M, Ikeda N, Taketomi A, Asahi Y, Takesue Y, Orimo T, et al. COVID-19: clinical issues from the Japan Surgical Society. Surg Today. 2020;50:794–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02047-x.

Grass F, Behm KT, Duchalais E, Crippa J, Spears GM, Harmsen WS, et al. Impact of delay to surgery on survival in stage I-III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:455–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.11.513.

Kompelli AR, Li H, Neskey DM. Impact of delay in treatment initiation on overall survival in laryngeal cancers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:651–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818803330.

Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY, Guallar E, Hwang SS, Cho B, et al. Delay to curative surgery greater than 12 weeks is associated with increased mortality in patients with colorectal and breast cancer but not lung or thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2468–76. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-2957-y.

Al-Jabir A, Kerwan A, Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Khan M, Sohrabi C, et al. Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice-part 2 (surgical prioritisation). Int J Surg. 2020;79:233–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.002.

Japan Surgical Society. Recommendations for the provision of surgical care for the convergence of a new coronavirus pandemic. 2020. http://www.jssoc.or.jp/aboutus/coronavirus/info20200522.html. Accessed 08 Sept 2020.

Al-Omar K, Bakkar S, Khasawneh L, Donatini G, Miccoli P. Resuming elective surgery in the time of COVID-19: a safe and comprehensive strategy. Updates Surg. 2020;72:291–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00822-6.

Isogai T, Matsui H, Tanaka H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. In-hospital management and outcomes in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy: a descriptive study using a national inpatient database in Japan. Heart Vessels. 2017;32:944–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-017-0958-7.

Isogai T, Matsui H, Tanaka H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Seasonal variation in patient characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of Takotsubo syndrome: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Japan. Heart Vessels. 2017;32:1271–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-017-1007-2.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Reports of a survey, “discharged patients survey,” for assessing the effects of introducing DPC, 2018. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000196043_00003.html. Accessed 13 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Dynamic survey of medical institutions and hospital report, 2018. 2018. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/m18/is1802.html. Accessed 13 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

Sharabiani MTA, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50:1109–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. On the use of the national database of health insurance claims and specific health checkups of Japan. 2013. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r9852000002ss9z-att/2r9852000002ssfg.pdf. Accessed 30 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098.

Fligor SC, Wang S, Allar BG, Tsikis ST, Ore AS, Whitlock AE, et al. Gastrointestinal malignancies and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence-based triage to surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04712-5.

Colombo I, Zaccarelli E, Del Grande M, Tomao F, Multinu F, Betella I, et al. ESMO management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID-19 era: gynaecological malignancies. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000827. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000827.

American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: guidance for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures. 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

Stensland KD, Morgan TM, Moinzadeh A, Lee CT, Briganti A, Catto JWF, et al. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020;77:663–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027.

Memon SF, Khattab N, Abbas A, Abbas AR. Surgical prioritization of obstetrics and gynecology procedures in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150:409–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13280.

The Japanese Red Cross. 2020. https://www.bs.jrc.or.jp/ktks/bbc/2020/04/post-69.htm. Accessed 8 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

Stover PE, Siegel LC, Parks R, Levin J, Body SC, Maddi R, et al. Variability in transfusion practice for coronary artery bypass surgery persists despite national consensus guidelines: a 24-institution study. Institutions of the Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:327–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199802000-00009.

NHS England, Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Royal College of surgeons of Edinburgh, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Clinical guide to surgical prioritisation during the coronavirus pandemic. 2020. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/surgical-prioritisation-guidance/. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

American College of Surgeons. COVID-19 guidelines for triage of vascular surgery patients. 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/vascular-surgery. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

The Japanese Society for cardiovascular surgery statement on SARS-CoV-2 infection measures. 2020. https://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jscvs/member-corona0406/. Accessed 30 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

Khalafallah AM, Jimenez AE, Lee RP, Weingart JD, Theodore N, Cohen AR, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on an academic neurosurgery department: the Johns Hopkins experience. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e877–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.167.

Mohile NA, Blakeley JO, Gatson NT, Hottinger AF, Lassman AB, Ney DE, et al. Urgent considerations for the neuro-oncologic treatment of patients with gliomas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neuro-Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noaa090.

The Japan Neurosurgical Society. Guidelines for neurosurgery for new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) ver.1.0. http://jns.umin.ac.jp/topics/20200515/11179. Accessed 30 Sept 2020. (in Japanese).

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, Maintaining Trauma Center Access & Care during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance document for Trauma Medical Directors. 2020. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/ maintaining-access. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

Japanese Ophthalmological Society. Attitudes towards ophthalmic surgery during an outbreak of a new coronavirus infection. http://www.nichigan.or.jp/news/069.jsp. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

The Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society of Japan. A guide to dealing with otorhinolaryngological surgery during the epidemic of the COVID-19. 2020. http://www.jibika.or.jp/members/information/info_corona.html. Accessed 30 Sept 2020.

Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. Statement from the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association regarding Elective Surgery and COVID-19. 2020. https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-statement. Accessed 8 Sept 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff members and all the participating acute care hospitals. Our database using in this research cannot be available publicly because of their nature (the data of Japanese government).

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19H01075 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, GAP Fund Program of Kyoto University type B, and Health Labor Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan [H29-shinkogyosei-shitei-005] to Y.I. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

595_2021_2286_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file2 (PDF 11 KB) Supplementary Fig. 1. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within oncological surgeries. HPB, Hepato-pancreato-biliary

595_2021_2286_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file3 (PDF 16 KB) Supplementary Fig. 2. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within abdominal surgeries. Supplementary Fig. 3. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within genitourinary surgeries. Supplementary Fig. 4. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within cardiovascular surgeries

595_2021_2286_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file4 (PDF 13 KB) Supplementary Fig. 5. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within neurosurgeries. Supplementary Fig. 6. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within orthopedic surgeries. ORIF, Open reduction internal fixation

595_2021_2286_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file5 (PDF 13 KB) Supplementary Fig. 7. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within ophthalmologic surgeries. Supplementary Fig. 8. Year-over-year trend in number by major surgical type within Ear/Nose/Throat surgeries. ESS, Endoscopic sinus surgery

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okuno, T., Takada, D., Shin, Jh. et al. Surgical volume reduction and the announcement of triage during the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a cohort study using an interrupted time series analysis. Surg Today 51, 1843–1850 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-021-02286-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-021-02286-6