Abstract

Over the last twenty years, there has been a discernable increase in the number of scholars who have focused their research on metal production, working and use in antiquity, a field of study which has come to be known as ARCHAEOMETALLURGY. Materials scientists and conservators have worked primarily in the laboratory while archaeologists have conducted fieldwork geared to the study of metal technology in a cultural context with laboratory analysis as one portion of the interpretive program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes and References

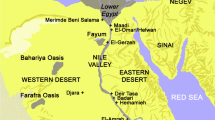

B. Rothenberg, “Ancient Copper Industries in the Western Arabah,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 94 (1962), pp. 5–71. For later publications of the Timna project, see B. Rothenberg, Were These King Solomon’s Mines? Excavations in the Timna Valley, New York (Stein and Day) 1972; and H.C. Conrad and B. Rothenberg, eds., Antikes Kupfer im Timna-Tal, Bochum (Bergbau Museum) 1980 (Der Anschnitt, Beiheft 1).

N. Glueck, “Eziongeber,” Biblical Archaeologist, 28 (1965), pp. 70–78. In spite of this retraction, attempts are still made, from time to time, to revive the image of Solomon the Copper King, most recently by J.J. Bimson, “King Solomon’s Mines? A Re-assessment of Finds in the Arabah,” Tyndale Bulletin, 32 (1981), pp. 123-149. It is not without significance that Bimson is a follower of the theories of the late Immanuel Velikovsky. For this school of thought, the fact that nothing from the Wadi Arabah dates to the 10th century B.C. is but further proof for their position that Solomon’s reign should properly be placed in the 8th century B.C.

H.G. Bachmann and B. Rothenberg, “Die Verhüttungsverfahren von Site 30,” Antikes Kupfer im Timna-Tal, Bochum, 1980, pp. 215–236.

B. Rothenberg, “Copper Smelting Furnaces in the Arabah, Israel: The Archaeological Evidence,” Furnaces and Smelting Technology in Antiquity, P. Craddock and M.J. Hughes, eds., London, 1985 (British Museum Occasional Paper No. 18), pp. 183–217.

M. Bamberger, P. Wincierz, H.G. Bachmann and B. Rothenberg, “Ancient Smelting of Oxide Copper Ore. Evidence at Timna and Experimental Approach,” Metall, 40 (1986), pp. 1166–1174.

H.G. Bachmann and A. Hauptmann, „Zur alten Kupfer-gewinnung in Fenan und Hirbet en-Nahas im Wadi Arabah in Südjordanien,” Der Anschnitt, 36 (1984), pp. 110–123.

A. Hauptmann, G. Weisgerber and E.A. Knauf, „Archäometallurgische und bergbauarchäologische Untersuchungen im Gebiet von Fenan, Wadi Arabah (Jordanien),” Der Anschnitt, 37 (1985), pp. 163–195.

A. Hauptmann, „Die Gewinnung von Kupfer: Ein uralter Industriezweig auf der Ostseite des Wadi Arabah,” Petra, Neue Ausgrabungen und Entdeckungen, M. Lindner, ed., Delp Verlag, Munich, (1986), pp. 31–43.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Editor’s Note: As it appears in the October Journal of Metals, Part One of “King Solomon’s Mines: A 20th Century Myth” explains how one man, American archaeologist Nelson Glueck, erroneously interpreted the excavated site of Tell el-Kheleifeh as being King Solomon’s giant refining installation where smelted copper was refined for casting. Both installments have been adapted by the author from his article “Solomon, the Copper King,” which originally appeared during 1987 in the magazine Expedition.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muhly, J.D. King Solomon’s Mines: A 20th Century Myth. JOM 40, 36–37 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03258792

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03258792