Abstract

Quantitation of urinary cotinine, a major metabolite of nicotine, by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), was performed in parallel with questionnaires containing items on smoking status, such as active and/or passive smokers, the number of cigarettes smoked, and the presence or absence of active smokers in the surroundings in a department store (517 employees). The cotinine values corrected by creatinine (cotinine-creatinine ratios, CCRs) approximately conformed to the extent of self-recognition of their exposure status to tobacco-smoke, and were low in the order of active smokers, passive smokers and non-smokers who felt they were not exposed to tobacco-smoke. Occupational differences of the CCRs were not found in the employees.

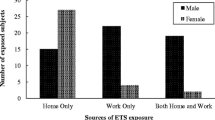

In the active smokers, the CCRs were increasing according to the number of cigarettes per day they smoked, and the values were nearly proportional to nicotine contents of cigarette in the moderate smokers who smoked 11-20 cigarettes per day. The CCRs of males were higher than those of females in the active smokers, which also agreed well with the numbers of cigarettes they smoked per day. In the passive smokers, the CCRs were remarkably and significantly higher in subjects who felt they were exposed to tobacco-smoke both in their workplaces and homes.

Urinary CCRs measured by ELISA are thus found to be a reliable and excellent objective indicator of both active and passive exposure-status to tobacco-smoke.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute on Health and Welfare Affairs. Aiming at improvement in health and quality of life. In: The Ministry of Health and Welfare in Japan, editors. Annual Report on Health and Welfare. Tokyo; Dai-ichi Press Inc., 1995: 113–6 (in Japanese).

Survey of Tobacco Smoking in Japan. Tokyo: Japan Tobacco Incorporated, 1997. (in press)(in Japanese)

Tobacco smoking. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans. Lyon: IARC, 1986.

Walter WH, Roger D, George K. Oxford Textbook of Public Health: Influences of Public Health. Oxford: Oxford Med Publications, 1991.

Stock SL. Risks the passive smoker runs [letter]. Lancet 1980;2: 1082.

Rickert WS, Robinson JC, Collishaw N. Yields of tar, nicotine and carbon monoxide in the sidestream from 15 brands of Canadian cigarettes. Am J Publ Health 1984;74: 228–31.

Walter WH, Roger D, George K. Oxford Texbook of Public Health: Applications in Public Health. Oxford: Oxford Med Publications, 1991.

The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking, a Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986.

Hirayama T, Tominaga S, Ogawa H. Investigations into the results of the self-reported questionnaires concerning smoking and health. A Report of the Health Promotion Research Group. 1981:243–53. (in Japanese)

Kabat GC, Wynder EL. Lung cancer in nonsmokers. Cancer 1984;53: 1214–21.

Lee PN, Chamberlain J, Aldelson MR. Relationship of passive smoking to risk of lung cancer and other smoking-associated diseases. Br J Cancer 1986;54: 97–105.

Fontham ET, Correa P, Wu-Williams A, Reynolds P, Greenberg RS, Buffler PA, et al. Lung cancer in nonsmoking women: a multicenter case-control study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 1991:1:35–43.

Schwartz SL, Gastonguay MR, Robinnson DE, Batler NJ. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Nicotine. In: Gorrod JW, Wahren J. editors. Nicotine and Related Alkaloids. New York, NY; Chapman & Hall, 1993: 255–74.

Yoshioka N, Dohi Y, Yonemasu K. Development of a simple and rapid ELISA of urinary cotinine for epidemiological application. Environ Health Prev Med 1998;3: 12–6.

Benowitz NL, Kuyt F, Jacob P 3rd, Jones RT, Osman AL. Cotinine disposition and effects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1983;34: 604–11.

Bonsnes RW, Taussky HH. On the colorimetric determination of creatinine by Jaffe reaction. J Biol Chem 1945;158: 581–91.

Dawson-Saunders B, Trapp RG. Basic & Clinical Biostatistics. In: ALANGE medical book, 2nd edition. Norwalk, CT; Prentice-Hall International Inc., 1994: 42–161.

Thompson SG, Stone R, Nanchahal K, Wald NJ. Relation of urinary cotinine concentrations to cigarette smoking and to exposure to other people’s smoke. Thorax 1990;45: 356–61.

Langone JJ, Cook G, Bjercke RJ, Lifschitz MH. Monoclonal antibody ELISA for continine in saliva and urine of active and passive smokers. J Immunol Methods 1988;114: 73–8.

Coultas DB, Peake GT, Samet JM. Questionnaire assessment of lifetime and recent exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130: 338–47.

Marbury MC, Hammond SK, Haley NJ. Measuring exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in studies of acute health effects. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137: 1089–97.

Bakuola CG, Kafritsa YJ, Kavadias GD, Lazopoulou DD, Theodoridou MC, Maravelias KP, et al. Objective passive-smoking indicators and respiratory morbidity in young children. Lancet 1995;346: 280–1.

Wald NJ, Nanchahal K, Thompson SG, Cuckle HS. Does breathing other people’s tobacco smoke cause lung cancer? Br Med J 1986;293: 1217–22.

Rubin DH, Krasilnikoff PA, Leventhal JM, Weile B, Berget A. Effect of passive smoking on birth-weight. Lancet 1986;23: 415–7.

Martin TR, Gracken MB. Association of low birth weight with passive smoke exposure in pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124: 633–42.

Ogawa H, Tominaga S, Hori K, Noguti K, Kanou I, Matsubara M. Passive smoking by pregnant women and fetal growth. J Epidemiol Comm Health 1991;45: 164–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshioka, N., Yonemasu, K., Dohi, Y. et al. Active and passive exposure status to tobacco smoke of department store employees measured by cotinine ELISA. Environ Health Prev Med 3, 83–88 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02931789

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02931789