Abstract

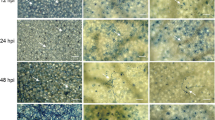

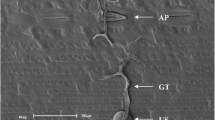

The susceptibility of leaves and berries of five night-shade species to infection by the potato late blight pathogenPhytophthora infestans was tested. American black nightshade (Solanum americanum) and eastern black nightshade (Solanum ptycanthum) were resistant to infection. However, two accessions (entire-edged and dentate-edged leaf) of hairy nightshade (Solanum sarrachoides), cutleaf nightshade (Solanum triflorum), and bitter or climbing nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) were susceptible. Survival of the pathogen in susceptible species was tested under different environmental conditions. The pathogen survived for at least 2 wk in both hairy nightshade accessions when plant material was kept in soil at a temperature of 20 C. However,P. infestans survived 48 h at −15 C only in the entire-leaf hairy nightshade accession. In the laboratory, oospores of the pathogen were formed in inoculated plants of the two hairy nightshade accessions, cutleaf nightshade, and ‘Russet Burbank’ potato, but not in American black nightshade, bitter nightshade, or eastern black nightshade.

Resumen

Se probó la susceptibilidad a la infección del patógeno del tizón tardíoPhytophthora infestans en hojas y bayas de cinco especies de dulcamara (hierba mora). Fueron resistentes a la infección la dulcamara negra americana (Solanum americanum) y la dulcamara negra del este (Solanum ptycanthum). Sin embargo, dos accesiones (de hoja lisa y hoja dentada) de la dulcamara pilosa (Solanum sarrachoides), dulcamara de hoja partida (Solanum triflorum) y dulcamara amarga o trepadora (Solanum dulcamara) fueron susceptibles. La supervivencia del patógeno en las especies susceptibles se probó bajo diferentes condiciones de medio ambiente. El patógeno sobrevivió por lo menos por dos semanas en ambas accesiones pilosas cuando la planta se mantuvo en el suelo a una temperatura de 20 C. Sin embargo,P. infestans sobrevivió 48 horas a −15 C solamente en la accesión de dulcamara de hoja pilosa entera. En el laboratorio, las oosporas del patógeno se formaron en las plantas inoculadas de dos accesiones pilosas, dulcamara de hoja partida y la variedad Russet Burbank pero no en la dulcamara negra americana, la dulcamara amarga o en la dulcamara negra del este.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature cited

Andrivon D. 1994. Dynamics of the survival and infectivity to potato tubers of sporangia ofPhytophthora infestans in three different soils. Soil Biol Biochem 26:945–952.

Brasier CM, DEL Cooke and JM Duncan. 1999. Origin of a newPhytophthora pathogen through interspecific hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96(10): 5878–5883.

Caten CE and JL Jinks. 1968. Spontaneous variability of single isolates ofPhytophthora infestans. I. Cultural variation. Can J Bot 46:329–348.

Cohen Y, S Farkash, Z Reshit and A Baider. 1997. Oospore production ofPhytophthora infestans in potato and tomato leaves. Phytopathology 87:191–196.

Dandurand LM and CV Eberlein. 2000. Susceptibility of five neightshade (Solanum) species toPhytophthora infestans. Am Phytopathol Soc Pub No P-2000-0015-PCA.

Drenth A, EM Janssen and F Govers. 1995. Formation and survival of oospores ofPhytophthora infestans under natural condition. Plant Pathol 44:86–94.

Eberlein CV, MJ Guttieri and WC Schaffers. 1992. Hairy nightshade (Solanum sarrachoides) control in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) with bentazon plus additives. Weed Tech 6:85–90.

Fay JC and WE Fry. 1997. Effects of hot and cold temperatures on the survival of oospores produced by United States strains ofPhytophthora infestans. Am Potato J 74:315–323.

Flier WG, GBM van den Bosch and LJ Turkensteen. 2003. Epidemiological importance ofSolanum sisymbriifolium, S. nigrum andS. dulcamara as alternative hosts forPhytophthora infestans. Plant Pathol 52:595–603.

Fry WE and SB Goodwin. 1997. Re-emergence of potato and tomato late blight in the United States. Plant Dis 81:1349–1357.

Fyfe AM and DS Shaw. 1992. An analysis of self-fertility in field isolates ofPhytophthora infestans. Mycol Res 96:390–394.

Gavino PD, CD Smart, RW Sandrock, JS Miller, PB Hamm, TY Lee, RM Davis and WE Fry. 2000. Implications of sexual reproduction forPhytophthora infestans in the United States: generation of an aggressive lineage. Plant Dis 84:731–735.

Kirk WW. 2003. Tolerance of mycelium of different genotypes ofPhytophthora infestans to freezing temperatures for extended periods. Phytopathology 93:1400–1406.

Lacey J. 1965. The infectivity of soils containingPhytophthora infestans. Ann Appl Biol 56:363–380.

MacKenzie DR, VR Elliott, BA Kidney, ED King, MH Royer and RL Theberge. 1983. Application of modern approaches to the study of the epidemiology of diseases caused byPhytophthora.In: DC Erwin, S Bartnicki-Garcia and PH Tsao (eds),Phytophthora: Its Biology, Taxonomy, Ecology, and Pathology. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN. pp 303–313.

Medina MV and HW Platt. 1999. Viability of oospores ofPhytophthora infestans under field conditions in northeastern North America. Can J Plant Pathol 21:137–143.

Malajczuk N. 1983. Microbial antagonism toPhytophthora.In: DC Erwin, S Bartnicki-Garcia and PH Tsao (eds),Phytophthora: Its Biology, Taxonomy, Ecology, and Pathology. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN. pp 197–218.

Pittis JE and RC Shattock. 1994. Viability, germination and infection potential of oospores ofPhytophthora infestans. Plant Pathol 43:387–396.

Platt HW. 1999. Response of solanaceous cultivated plants and weed species to inoculation with A1 or A2 mating type strains ofPhytophthora infestans. Can J Plant Pathol 21:301–307.

Vartanian VG and RM Endo. 1985. Overwintering hosts, compatibility types, and races ofPhytophthora infestans on tomato in southern California. Plant Dis 69:516–519.

Zan K. 1962. Activity ofPhytophthora infestans in soil in relation to tuber infection. Trans Brit Mycol Soc 45:205–221.

Zwankhuizen MJ, F Govers and JC Zadoks. 1998. Development of potato late blight epidemics: disease foci, disease gradients and infection sources. Phytopathology 88:754–763.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dandurand, L.M., Knudsen, G.R. & Eberlein, C.V. Susceptibility of five nightshade (Solanum) species tophytophthora infestans . Am. J. Pot Res 83, 205–210 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02872156

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02872156