Abstract

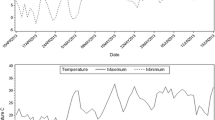

Freshly harvested Norchip and Kennebec tubers release varied amounts of methyl chloride (CH3Cl) during suberization. Maximum rates of CH3Cl release, ranging from 98-690 ng CH3Cl/kg tubers/hr under laboratory and commercial conditions, were attained 2–3 days following harvest. Release rates thereafter decreased 10-40-fold by the 7th day of suberization. The period of rapid decrease in CH3Cl release corresponds to the reported time required by cut tuber tissue to initiate resistance to water loss. Cutting of newly harvested and suberized Kennebec tubers reestablished the high release rates of CH3Cl measured during the early stages of suberization. The enhancement of CH3Cl release by tissue cutting was not demonstrated by two varieties stored for 10 months. Suberization differences between early and late harvested Norchip tubers were better differentiated by their respective rates of CH3Cl release than by CO2 generation. These preliminary findings suggest the rate of CH3Cl release could be applied to assess harvest damage and monitor the suberization process. Methyl chloride has previously been reported as the major nonindustrial chlorocarbon in the atmosphere that is linked to a replenishable, natural source.

Resumen

Tubérculos de las variedades Norchip y Kennebec cosechados frescos liberan cantidades variables de cloruro de metilo (CH3Cl) durante la suberización.

Las tasas de producción de CH3Cl, que fluctuaron entre 98-690 ng de CH3Cl por kg de tubérculos por hors bajo condiciones de laboratorio y comerciales, fueron alcanzadas 2 á 3 días después de la cosecha. Estas tasas disminuyeron 10 á 40 veces al 7mo día de suberización. El período de rápida disminución de producción de CH3Cl corresponde al período requerido por los tejidos del tubérculo cortada en iniciar resistencia a la pérdida de agua. Cortar tubérculos recién cosechados y suberizados de la variedad Kennebec, reiniciaron alta producción de CH3Cl medida durante los primeros estados de suberización. El estimular la producción de CH3Cl mediante el cortar tejidos, no fué obtenido por dos variedades almacenadas por 10 meses. Las diferencias en suberización entre tubérculos de la variedad Norchip, cosechados temprano y tardiamente, fueron diferenciados más claramente por sus respectivas tasas de producción de CH3Cl que por la generación de CO2. Estos resultados preliminares sugieren que la tasa de producción de CH3Cl podría ser aplicada para evaluar daños de cosecha y para seguir el proceso de suberización. El cloruro de metilo ha sido mencionado antes como el mayor producto clorocarbonado no industrial en la atmósfera, que está relacionado a una fuente natural reproducible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Appleman, C.O., W.D. Kimbrough, and C.L. Smith. 1928. Physiological shrinkage of potatoes in storage. University of Maryland Agricultural Bulletin 303:159–175.

Bakhishev, G.N. 1973. Relative toxicity of aliphatic halocarbons to rats. Farmakol Toksikol (Mosc) 8:140–142.

Cox, R.A., R.F. Derwent, A.E.J. Eggleton, and J.E. Lovelock. 1976. Photochemical oxidation of halocarbons in the troposphere. Atmos Environ 10:305–308.

Crutzen, P. J., I.S.A. Isaksen, and J.R. McAfee. 1978. The impact of the chlorocarbon industry on the ozone layer. J Geophys Res 83:345–363.

Grimsrud, E.P. and R.A. Rasmussen. 1975. Survey and analyses of halocarbons in the atmosphere by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Atmos Environ 9:1014–1017.

Index of Mass Spectra Data. 1969. ASTM Committee E-14 on Mass Spectroscopy, American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, PA, pg. 2.

Jarvis, M.C. and H.J. Duncan. 1979. Water loss from potato tuber discs: a method for assessing wound healing. Potato Res 22:69–73.

Kadaba, P.K., P.K. Bhagat, and G.N. Goldberger. 1978. Application of microwave spectroscopy for simultaneous detection of toxic constituents in tobacco smoke. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 19:104–112.

Kolattukudy, P.E. and B.B. Dean. 1974. Structure, gas Chromatographic measurement, and function of suberin synthesized by potato tuber tissue slices. Plant Physiol 54:116–121.

Lovelock, J.E. 1975. Natural halocarbons in air and sea. Nature 258:775–776.

Paterson, M.I. and E.G. Gray. 1972. The formulation of wound periderm and the susceptibility of potato tubers to gangrene (caused byPhoma exigua) in relation to rate of fertilizer application and time of planting. Potato Res 15:1–11.

Reynolds, E.S. and A.G. Yee. 1967. Liver parenchymal cell injury.V. Relation between patterns of chloromethane-14C incorporation into constituents of liverin vivo and cellular injury. Lab Invest 16:591–603.

Schaper, L.A. and J.L. Varns. 1978. Carbon dioxide accumulation and flushing in potato storage bins. Am Potato J 55:1–14.

Schippers, P.A. 1971. The influence of curing conditions on weight loss of potatoes during storage. Am Potato J 48:278–286.

Singh, H.B., L. J. Salas, H. Shiglishi, and E. Scribner. 1979. Atmospheric halocarbons, hydrocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride: global distribution, sources, and sinks. Science 203:899–903.

Turner, E.M., M. Wright, T. Ward, D.J. Osborne, and R. Self. 1975. Production of ethylene and other volatiles and changes in cellulase and laccase activities during the life cycle of the cultivated mushroom.Agaricus bisporus. J Gen Microbiol 91:167–176.

Varns, J.L. and M.T. Glynn. 1979. Detection of disease in stored potatoes by volatile monitoring. Am Potato J 56:185–197.

Watson, E.L. and L.M. Staley. 1963. Heat transfer rates in a model potato bin. Can Soc Agric Engr J 5:34–40.

Workman, M., E. Kerschner, and M. Harrison. 1976. The effect of storage factors on membrane permeability and sugar content of potatoes and decay byErwinia carotovora var.atroseptica andFusarium roseum var.sambucinum. Am Potato J 53:191–204.

Zafiriou, O.C. 1975. Reactions of methyl halides with seawater and marine aerosols. J Mar Res 33:75–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This is a Laboratory cooperatively operated by the United States Department of Agriculture; the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station; the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station; and the Red River Valley Potato Grower’s Association.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Varns, J.L. The release of methyl chloride from potato tubers. American Potato Journal 59, 593–604 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02867599

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02867599