Abstract

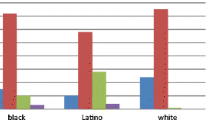

This article disputes the argument and the evidence used to conclude that white workers are hurt by discrimination against blacks. Racism may increase the bargaining power of white workers if it unifies white ethnics, and may benefit them if it reduces job competition. The distributional consequences of discrimination will vary with the intensity of aggregate unemployment and the degree of racial segmentation in the labor market. The impact of racial inequality on the probability of employment is evaluated with a cross-sectional model using census summary data on SMSAs. Results show that racial inequality improves white male and female employment prospects in 1980, and suggest the same for 1970.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Samuel Bowles, “The Production Process in a Competitive Economy: Walrasian, Neo-Hobbesian, and Marxian Models,”American Economic Review, Volume 75 (September 1985).

For example, see Michael Reich,Racial Inequality: A Political-Economic Analysis (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981); John E. Roemer, “Divide and Conquer: Microfoundations of a Marxian Theory of Wage Discrimination,”Bell Journal of Economics, Volume 10 (Autumn 1979); and Albert Syzmanski, “Racial Discrimination and White Gain,”American Sociological Review, Volume 41, (June 1976).

For example, see E. M. Beck, “Discrimination and White Economic Loss: A Time Series Examination of the Radical Model,”Social Forces, Volume 59 (September 1980); and Norman R. Cloutier, “Who Gains From Racism? The Impact of Racial Inequality on White Income Distribution,”Review of Social Economy, Volume XLV (October 1987).

Erik Olin Wright,Class Structure and Income Determination, (NY: Academic Press, 1979), p. 202.

Herbert Hill, “Black Labor and Affirmative Action: An Historical Perspective,” inThe Question of Discrimination: Racial Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market (Steven Shulman and William Darity, Jr., eds., Wesleyan University Press, 1989); Daniel R. Fusfeld and Timothy Bates,The Political Economy of the Urban Ghetto (Carbondale IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), pp. 179-190; Edna Bonacich, “Advanced Capitalism and Black/White Race Relations in the United States: A Split Labor Market Interpretation,”American Sociological Review, Volume 41 (February 1976); William Darity, “What’s Left of the Economic Theory of Discrimination?” InThe Question of Discrimination, op. cit.

Edna Bonacich, “Class Approaches to Ethnicity and Race,”Insurgent Sociologist 10 (Fall 1980), p. 14.

Reich, op. cit., p. 311. The only effort by Reich to use an absolute measure of distributional impact (which he agrees is a more “direct test”) is in his Table 7.6 (p. 302). He uses median white earnings across industries as the dependent variable, and attempts to show that they are positively correlated with the ratio of nonwhite-to-white earnings. The equation, however, is unconvincing. First, he includes an age variable whose coefficient is significantlynegatively correlated with earnings. Second, he includes (without justification) a percent nonwhite variable whose coefficient is also significantly negative. If white earnings go up when nonwhite employment goes down, then it could be concluded that whites make wage gains from employment discrimination against blacks.

Hill, op. cit.

See Elizabeth Moss Kanter,Men and Women of the Corporation (NY: Basic Books, 1977), for a discussion of this process with respect to the sex typing of occupational roles.

For example, see Thomas Sowell,Markets and Minorities (NY: Basic Books, 1981).

Steven Shulman, “Competition and Racial Discrimination: The Employment Effects of Reagan’s Labor Market Policies,”Review of Radical Political Economics, Volume 16 (Winter 1984).

Richard Edwards and Michael Podgursky, “The Unraveling Accord: American Unions in Crisis,” inUnions in Crisis and Beyond, ed., R. Edwards, et. al. (Dover MA: Auburn House, 1982).

Herbert Hill, “The AFL-CIO and the Black Worker: Twenty-five Years After the Merger,”The Journal of Intergroup Relations, Volume 10 (Spring 1982).

Edwards and Podgursky, op. cit., for example, comment that the accord—which they partially credit for the productivity increases of the period-“primarily organized white male workers” (p. 21).

Edwards and Podgursky, op. cit., pp. 28–34.

Reynolds Farley,Blacks and Whites: Narrowing the Gap? (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1984), pp. 16–22, 46–50.

Reich, op. cit., ch. 4.

Cloutier, op. cit.; Beck, op. cit.

Rhonda M. Williams, “Capital, Competition, and Discrimination: A Reconsideration of Racial Earnings Inequality,”Review of Radical Political Economics, Volume 19 (Summer 1987), p. 6.

Cloutier, op. cit., fails to replicate Reich’s results with the use of 1980 census summary data on an expanded set of SMSAs. Beck, op. cit., finds no support for the solidarity effect using time-series data. He describes Reich’s findings as “spurious” because “the positive relationship . . . between the income ratio and white economic status may be the result of both terms covarying with changes in the demand for labor” (p. 162). Sysmanski, op. cit., does replicate Reich’s results, but only by committing the same econometric errors. 21. Nassau is not listed separately in the 1970 census. The sample size for the 1970 equations is therefore 49. There is no reason to believe that this difference between the 1970 and 1980 sample biases the results. White variables for 1970 are computed as total minus black minus Spanish speaking. 22. One obvious objection that might arise at this point is the possibility of simultaneity since causality could clearly run from unemployment to family incomes, i.e., from the left side of the equation to the right side. However, the census income data is from the year prior to the decennial year, while the unemployment data is on the decennial year itself. Since unemployment in the decennial year cannot be held to influence family incomes in the year prior, simultaneity is not a problem here. As noted in the text, the same is not true of Reich’s specification: his dependent variables are drawn on 1969 data while his control variables are drawn on 1970 data.

Elsewhere I show that EEOC complaints of discrimination (as a proxy for actual discrimination) are positively correlated with the probability of white employment and negatively correlated with the probability of black employment. The impact is approximately twice as strong in the black female equation as in the black male equation. Why this would be the case is uncertain, although it may have to do with the interaction of race discrimination and sex discrimination. See Steven Shulman, “Discrimination, Human Capital and Black-White Unemployment: Evidence from Cities,”The Journal of Human Resources, Volume 22 (Summer 1987).

It is interesting to note the comparison in the mean values of UR/UR, in 1970 versus 1980. Almost no change is recorded for black women and little change for white men. In contrast, the ratio fell sharply for white women and rose sharply for black men. These changes reflect the employment advantages white women experienced in the expanding clerical and service sectors, and suggest that black men lost employment advantages as wage differentials declined. See Andrea Beller, “The Economics of Enforcement of an Antidiscrimination Law: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,”Journal of Law and Economics, Volume 21 (1978); and Shulman (1987), op. cit.

Wright, op. cit., p. 205, for example, states that “[b]lack and white workers may well have conflicting immediate interests under certain circumstances (as do many other categories of labor within the working class), and still share fundamental class interests.” In comparison to “fundamental” class interests, immediate interests are concrete and perceivable, and thereby may account for the failure of white workers to consistently fight racism. The distinction may sustain the classical Marxist analysis of racism, but it unfortunately does not simplify the problem of formulating political strategy.

Michael Omi and Howard Winant,Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 33.

About this article

Cite this article

Shulman, S. Racial inequality and white employment: An interpretation and test of the bargaining power hypothesis. Rev Black Polit Econ 18, 5–20 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02717872

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02717872