Abstract

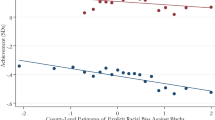

Most studies of the demand for private education have treated “white flight” as a response to the proportion of the population that is black in a particular area. The present article, by contrast, considers the possibility that this flight may be from poverty rather than race. The article develops an aggregate demand function for private education from which individual behavior may be inferred, and then applies the model to data from Mississippi. The results suggest that prejudice is directed against poor blacks rather than against nonpoor blacks or poor whites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,State and County Data Book (1983).

See Charles T. Clotfelter, “School Desegregation, ‘Tipping,’ and Private School Enrollment,”Journal of Human Resources, Volume 11, (1976), 28–50; Michael W. Giles, “White Enrollment Stability and School Desegregation: A Two Level Analysis,”American Sociological Review, Volume 43, (1978), 848–864; Jorge Martinez-Vazquez and Bruce A. Seaman, “Private Schooling and the Tiebout Hypothesis,”Public Finance Quarterly, Volume 13, (1985), 293–318; Christine H. Rossell, “School Desegregation and Community Social Change,”Law and Contemporary Problems, Volume 42, (1978), 133–183; and Jonathan Sandy, “Public and Private School Choice: The Influence of Public School Quality, Race, and Religion,” unpublished manuscript, University of San Diego, School of Business, 1988. Other papers treating private school choice, but not white flight, include Jon Sonstelie, “Public School Quality and Private School Enrollments,”National Tax Journal, Volume 32, (1979), 343–353 and Jon Sonstelie, “The Welfare Cost of Free Public Schools,”Journal of Political Economy, Volume 90 (1982), 794–807.

William J. Wilson,The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.)

Ibid., 92–96, 171.

“[I]t would be difficult to argue that the plight of the black underclass is solely a consequence of racial oppression... in the same way that it would be difficult to explain the rapid economic improvement of the more privileged blacks by arguing that the traditional forms of racial segregation and discrimination still characterize the labor market in American industries,” Ibid., 151–52.

Advocated by Milton Friedman,Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.)

The state of Mississippi is an interesting case study for several reasons. First, the state has a history of intense racial prejudice. Second, after federal desegregation rulings were put into effect, private schools were seen by many whites as the primary alternative to attendance in integrated schools (see Clotfelter, “School Desegregation”). Third, since southern states are more residentially integrated than northern states, white flight primarily takes the form of enrollment in private schools rather than migration to suburbs. This is especially the case in Mississippi, since it is one of the least urbanized states in the south. While Mississippi should be somewhat representative of the South, it may be less representative of the nation as a whole. It would therefore be interesting to apply our method to other states. Not only would this shed light on the general issue of the importance of class prejudice as opposed to race prejudice, but it would also be of interest in determining the effect of different social and economic structures on racial attitudes.

The fraction Catholic will be included as a control variable. This is common in studies of public/private school choice, because of the well-developed institution of parochial schools. See, for example, Clotfelter, 37–40, Sonstelie, “Public School Quality,” pp. 348-9, Sonstelie, “The Welfare Cost,” p. 802, and Sandy, “Public and Private School Choice” pp. 10, 18. While Catholics represent only a small fraction of the population, it is important to control for their presence, since their concentration in certain counties could have a significant effect on our results. (In Mississippi, Catholics tend to be concentrated in countries bordering Louisiana, for example.) In addition, inclusion of Catholics illustrates how our method must be adapted to data sets in which data on families is not completely cross-tabulated. (We have data on families cross-tabulated by race and income group, but not by race, income group and religion.) This may be of interest to others who may want to use a similar approach.

We would expect that some people choose private schools for quality reasons. Evidence based on national data shows that students in private schools generally perform better than their counterparts in public schools, as measured by test scores for students at different grade levels. Likewise, there are significant differences between public and private schools in resources available to students as measured, say, by student-teacher ratios. On the other hand, the quality of teachers (as measured by percentage of teachers who hold master’s degrees, for example) appears to be roughly equal in public and private schools. For a comprehensive analysis of differences between public and private schools, see James S. Coleman, Thomas Hoffer, and Sally Kilgore,High School Achievement: Public, Catholic, and Private Schools Compared (New York: Basic Books, 1982.) We were unable to obtain data on private school tuition or quality by county in Mississippi for this study. The difficulty of obtaining detailed private school data has, in fact, plagued most studies in this area (see the references in footnote 2 above, for example). However, unless the schedule of available private school opportunities (our T(S) function) varies systematically with our other independent variables, the lack of detailed private school data should not significantly bias our results. Any possibility of systematic variation (say from economies of scale due to initial white flight) would, however, increase the value of some sort of survey data on private schools. A closer look at private school quality would, in any case, merit future research.

Data on per capita public school spending and number of school districts are from Mississippi State University, Division of Research, College of Business and Industry,Mississippi Statistical Abstract, 1982. Data for white income groups, white private school enrollment, racial composition by county, and poverty rates by race are from U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,1980 Census of Population, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 26, Mississippi, 1983. BPR is calculated by multiplying the fraction of the population which is black by the fraction of the black population which is poor. Thus, BPR is the fraction of the total population which is poor black. A similar procedure is used for BNPR and WPR. Data on Catholic population by county were obtained from the offices of the Vicars General of the Dioceses of Jackson and Biloxi and are available from the authors upon request. In counties for which data on both whites and blacks would reveal information about remaining racial groups which are so small that individual confidentiality would be violated, the Census reports suppress the data on one of the larger racial groups (white or black) to preserve anonymity. In the small number of counties where this occurred, we subtracted data for the reported racial group from the total numbers to obtain an estimate for the other racial group. Since this “complementary suppression” is used only when remaining racial groups are very small, this method should not introduce any biases.

See note 3.

Elchanan Cohn,The Economics of Education (Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing, 1979), p. 305.

About this article

Cite this article

Conlon, J.R., Kimenyi, M.S. Attitudes towards race and poverty in the demand for private education: The case of Mississippi. The Review of Black Political Economy 20, 5–22 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02689924

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02689924