Abstract

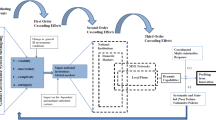

This article examines the conditions under which firms in different economies were able to emerge as significant actors in the global computer industry during different time periods. To achieve this, the article divides into three periods the history of the industry in terms of the three major policy regimes that have supported the dominant firms and regions. It argues that these policy regimes can be thought of as state developmentalisms that take significantly different forms across the history of the industry. U.S. firms’ dominance over their European counterparts in the 1950s and 1960s was underpinned by a system of “military developmentalism” where military agencies funded research, provided a market and developed infrastructure, but also demanded high quality products. The “Asian Tigers”—Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea—in the 1970s and 1980s were able to eclipse their Latin American and Indian rivals due in large part to the significant advantages offered by a highly effective system of “bureaucratic developmentalism,” where bureaucratic elites in key state agencies and leading business groups negotiated supports for export performance. The 1990s saw the emergence of a system of “network developmentalism” where countries such as Ireland and Israel were able to emerge as new nodes in the computer industry by careful economic and political negotiation of relations to the United States, reestablished at the center of the industry, and by more decentralized forms of provision of state support for high-tech development. Finally, the conditions under which new regimes can emerge are a consequence of the unanticipated global consequences of previous regimes. While state developmentalisms have been shaped by existing global regimes, they have promoted further and different rounds of industry globalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amin, A., and P. Cohendet. 2004.Architectures of Knowledge: Firms, Capabilities and Communities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amsden, A. 1985. “The State and Taiwan’s Economic Development” In P. Evans et al., eds.,Bringing the State Back In. Pp. 78–106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— 1989. Asia’s Next Giant:South Korea and Late Industrialization Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— 2001.The Rise of “the Rest”: Challenges to the West from Late-Industrializing Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arora, A., A. Gambardella, and S. Torrisi. 2000. “In the Footsteps of Silicon Valley? Indian and Irish Software in the International Division of Labor” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper 00-041.

Arrighi, G. 1999. “Globalization, State Sovereignty and the ‘Endless’ Accumulation of Capital” In D. Smith, D. Solinger, and S. Topik.States and Sovereignty in the Global Economy. Pp. 53–72 London and New York: Routledge.

Arrighi, G., and B. Silver. 2001.Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Borrus, M. 1997. “Left for Dead: Asian Production Networks and the Revival of US Electronics” BRIE Working Paper 100. Berkeley: Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy.

Braun, E., and S. MacDonald, 1978.Revolution in Miniature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brenner, R. 2002.The Boom and the Bubble. London: Verso.

Breznitz, D. 2005. “Collaborative Public Space in a National Innovation System: A Case Study of the Israeli Military’s Impact on the Software Industry.”Industry and Innovation (12,1): 31–64.

Burawoy M. 2001. “Neoclassical Sociology: From the End of Communism to the End of Classes”American Journal of Sociology 106, 4: 1099–1120.

Chibber, V. 1999. “Building a Developmental State: The Korean Case Reconsidered.”Politics and Society 27,3: 309–346.

Dedrick, J., and K.L. Kraemer. 1998.Asia’s Computer Challenge: Threat or Opportunity for the United States and the World? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dore, R. 1973.British Factory, Japanese Factory: The Origins of National Diversity in Industrial Relations. London and Boston: Allen and Unwin.

Evans, P.B. 1995.Embedded Autonomy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Evans, P.B., and J. Rauch. 1999. “Bureaucracy and Growth: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects of ‘Weberian’ States Structures on Economic Growth.”American Sociological Review 64: 748–765.

Flamm, K. 1987.Targeting the Computer: Government Support and International Competition. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Freeman, C., and J. Hagedoorn. 1994. “Catching Up or Falling Behind: Patterns in International Interfirm Technology Partnering”World Development 22, 5: 771–780.

Freeman, C., and Louca, F. 2002. As Time Goes by: From the Industrial Revolutions to the Information Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gereffi, G. 1994. “The International Economy” In N. Smelser and R. Swedberg, eds.,The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press/Russell Sage Foundation.

Gerlach, M. 1992.Alliance Capitalism: The Social Organization of Japanese Business. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gordon, R. 2001. “State, Milieu, Network: Systems of Innovation in Silicon Valley.” Center for Global, International and Regional Studies Working Paper #2001-3. University of California, Santa Cruz (originally distributed in February 1994).

Grieco, J. 1984.Between Dependency and Autonomy: India’s Experience with the International Computer Industry. University of California Press: Berkeley.

Harrison, B. 1994.Lean and Mean. New York: Basic Books

Hart, J., and S. Kim. 2001. “The Global Political Economy of Wintelism: A New Mode of Power and Governance in the Global Computer Industry,” in James N. Rosenau and J.P. Singh, eds., Information Technologies and Global Politics: The Changing Scope of Power and Governance Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press.

Held, D., A. McGrew, D. Goldblatt, and J. Perraton. 1999.Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Henderson, J. 1989.The Globalization of High Technology Production. New York: Routledge.

Hendry, J. 1989.Innovating for Failure: Government Policy and the Early British Computer Industry. Cambridge, MA MIT Press

Hobday, M. 1994. “Technological Learning in Singapore: A Test Case of Leapfrogging.”The Journal of Development Studies 30, 3: 831–858.

— 1995. “East Asian Latecomer Firms: Learning the Technology of Electronics”World Development 23, 7: 1171–1193.

Hsu, J.Y. 1997. “A Late Industrial Distrcomputer? Learning Networks in the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park.” Taiwan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley.

Huff, W. 1995. “The Developmental State, Government and Singapore’s Economic Development since 1960.”World Development (23, 8): 1421–38.

Johnson, C. 1982.MITI and the Japanese Miracle. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kim, L., and R. Nelson, 2000.Technology, Learning and Innovation: Experiences of Newly Industrializing Economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Langlois, R., and D. Mowery. 1996. “The Federal Government Role in the Development of the US Software Industry.” In D. Mowery, ed.,The International Computer Software Industry. Pp. 53–85. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lécuyer, C. 2000. “Fairchild Semiconductor and Its Influence.” In Chong-Moon Lee, William Miller, Marguerite Hancock, and Henry Rowen, eds.,The Silicon Valley Edge: A Habitat for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Leslie, S. 2000. “The Biggest ‘Angel’ of Them All: The Military and the Making of Silicon Valley” In M. Kenney, ed.,Understanding Silicon Valley. Pp. 48–69. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Loriaux, M. 1999. “The French Developmental State as Myth and Moral Ambition.” In M. Woo-Cumings, ed.,The Developmental State. Pp. 235–275. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lundvall, B.A., B. Johnson, E.S. Andersen, B. Dalum, 2002. “National Systems of Production, Innovation and Competence Building.”Research Policy (31,2): 213–231.

Luzio, E. 1996.The Microcomputer Industry in Brazil: The Case of a Protected High-Technology Industry. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Malerba, F. 2003. “Sectoral Systems: How and Why Innovation Differs Across Sectors.” In J. Fagerberg et al.,Oxford Handbook of Innovation. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

Markusen, A. P. Hall, and A. Glasmeier. 1986.High Tech America: The What, How, Where and Why of the Sunrise Industries. London and Boston: Allen and Unwin.

McKendrick, D. 2000.From Silicon Valley to Singapore. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

McNeil, W. 1982.The Pursuit of Power: Technology, Armed Force and Society since A.D. 1000. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Meaney, C. 1994. “State Policy and the Development of Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry” In J.D. Aberbach et al., eds.,The Role of the State in Taiwan’s Development. Pp. 170–192. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Mowery, D.C. 2001. “Technological Innovation in a Multipolar System: Analysis and Implications for U.S. Policy.”Technological Forecasting and Social Change 67: 43–157.

Newman, N. 2002. Net Loss:Government, Technology and the Political Economy of Community in the Age of the Internet. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

OECD. 2002.Information Technology Outlook 2002. Paris: OECD.

Ó Riain, S. 2000. “The Flexible Developmental State, Globalization, Information Technology and the ‘Celtic Tiger.’”Politics and Society 28, 3: 3–37.

— 2004.The Politics of High Tech Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parthasarathy, B. 2004. “India’s Silicon Valley or Silicon Valley’s India? Socially Embedding the Computer Software Industry in Bangalore.”International Journal of Urban and regional Research 28, 3: 664–685.

Perez, C. 2002.Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar.

Porter, A., J.D. Roessner, N. Newman, and X.Y. Jin. 2000.1999 Indicators of Technology-Based Competitiveness of 33 Nations: Summary Report. Washington D.C.: National Science Foundation.

Rodrik, D. 1997. “TFPG Controversies, institutions, and Economic Performance in East Asia” NBER Working Paper 5914, National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA.

Roper, S., and A. Frenkel. “Different Paths to Success? The Growth of the Electronics Sector in Ireland and Israel” Working Paper No. 39, Northern Ireland Economic Research Centre, Queen’s University, Belfast, 1998.

Saxenian, A. 1994.Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

— 1999.Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

Saxenian, A., and J. Y. Hsu. 2001. “The Silicon Valley-Hsinchu Connection: Technical Communities and Industrial Upgrading.”Industrial and Corporate Change 10, 4

Sokolov, M., and E. M. Verdoner. 1997. “The Israeli Innovation Support System—Generalities and Specifics” Working paper presented at Conference on Technology Policy and Less Developed Research and Development Systems in Europe, Seville, October.

Soskice, D., and P. hall, eds., 2001, Varieties of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steinmuller, E. 1996. “The U.S. Software Industry: An Analysis and Interpretive History.” In D. Mowery, ed.,The International Computer Software Industry. Pp. 15–52. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sturgeon, T. 2000. “How Silicon Valley Came to Be” In M. Kenney, ed.,Understanding Silicon Valley. Pp. 15–47. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

— 1999. “Network-Led Development and the Rise of Turn-key Production Networks: Technological Change and the Outsourcing of Electronics Manufacturing.” In G. Gereffi, F. Palpacuer, A. Parisotto, eds.,Global Production and Local Jobs. Geneva: International Institute for Labor Studies.

Vonortas, N. S., and S. P. Safioleas. 1997. “Strategic Alliances in Information Technology and Developing Country Firms: Recent Evidence.”World Development 25, 5: 657–680.

Wade, R. 1990.Governing the Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Woo-Cumings, M., ed., 1999.The Developmental State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Additional information

Seán Ó Riain is professor of sociology at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research has been primarily on the political economy of high-tech growth in Ireland and elsewhere, and on work and class politics among software developers. He is the author ofThe Politics of High Tech Growth: Developmental Network, States in the Global Economy (Cambridge, 2004).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ó Riain, S. Dominance and change in the global computer industry: Military, bureaucratic, and network state developmentalisms. St Comp Int Dev 41, 76–98 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686308

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686308