Samenvatting

In het Phytopathologisch Laboratorium „Willie Commelin Scholten” te Baarn werd van 1937–1939 en in 1946 een onderzoek ingesteld naar het parasitisme vanNectria cinnabarina (Tode)Fr.

1. Door het inoculeren van snoeiwonden aan een aantal houtgewassen met op kersagar gekweekt mycelium vanNectria cinnabarina wordt in een zeer groot aantal gevallen een voortschrijdende insterving van takken veroorzaakt. Het mycelium woekert daarbij in de jonge, wijde houtvaten verder.

2. Bij inoculatie van korte takken of takstompen, en in diepe insnijdingen door de bast, tot op het hout, zoals zij bij diep snoeien kunnen ontstaan, vormt zich in een minder groot aantal gevallen een schorsbrand-plek aan de basis van de takstomp of om de wond heen. Deze is het gevolg van de aantasting van het daaronderliggende hout, en is kleiner dan de verkleurde en geïnfecteerde houtzône, die zich vaak tot ver in de stam uitstrekt, voornamelijk in de oudere jaarringen. Ook deze vorm van inoculatie leidt in enkele gevallen tot insterving van takken en van de top van de boom.

3. Er blijkt uit de proeven, dat in het algemeen de infecties het best slagen vlak na het beëindigen van de winterrust, maar dat deze ook in andere jaargetijden (echter in de tijd van rijpe bebladering het minst duidelijk) kunnen optreden.

4. De virulentie van de gebruikte culturen vanNectria cinnabarina blijkt zeer uiteen te lopen. Bij voortdurend voortkweken van de mycelia op kunstmatige voedingsbodems verliezen zij hun virulentie. Naar alle waarschijnlijkheid is dit ook het geval met in de natuur vaak saprophytisch levendeNectria cinnabarina.

5. Bij experimenteren met dezelfde virulente cultuur blijkt, dat de vatbaarheid voor het taksterven, en de daardoor veroorzaakte misvormingen van de bomen van verscheidene factoren afhankelijk is:

-

a.

Er zijn meer en minder vatbare boomsoorten, ook bij nauwe verwanten treden verschillen op.

-

b.

Een bepaalde boomsoort is in elk jaargetijde verschillend voor infectie vatbaar. Vermoedelijk spelen daarbij voornamelijk de houtvaten en de enzymen die de vorming daarvan bewerken, een rol.

-

c.

Dikke takken en stammen, eenmaal van de top uit op de gehele doorsnede besmet, sterven sterker in dan dunne, één- of tweejarige.

-

d.

Pas verplante bomen hebben waarschijnlijk een geringere infectiekans (bij kunstmatige inoculatie) dan vaststaande. Wortelsnoei werkte beschermend, evenals schaduw, binnen zekere grenzen!

6. Vele boomsoorten reageren op de aanwezigheid vanNectria cinnabarina in hun houtvaten (in een zône van hun hout, waarin deze nog niet is doorgedrongen), zeer karakteristiek. Zo werden opgemerkt: Verkleuring van de middenlamellen der vaten, later ook der vezels en der secundaire wanden; vorming van gom in de vaten, van dezelfde kleur; vorming van thyllen in de vaten, tot het „beschermings- of wondhout” ontstaat; vorming van lacuniaire gangen tussen de mergstralen, die bij perzik en iep ontstaan; opzwellen en woekeren van het bastparenchym; vorming van secundaire cambia, die de wonden naar buiten afsluiten met een gaaf nieuw weefsel.

7. Takken, waarin zich nog geen der in 6 genoemde verschijnselen voordoen, maar die toch verwelken, worden afgesneden en in water gezet, weer fris. Er waren dus geen toxinen e.d. die het verwelken veroorzaakten in aan wezig, maar het afsnijden van de watertoevoer door het vormen van ondoorlaatbaar „beschermingshout” was daarvan de oorzaak.

8. In de voedingsoplossing waarin mycelium vanNectria cinnabarina groeit wordt een tegen koken bestand zijnde stof gevormd, die een groeiver hinderende werking heeft opPythium de Baryanum Hesse. De sterkst parasitaire mycelia vormden de sterkst groeiverhinderende stoffen binnen de kortste tijd (zes dagen).

9. Vormen vanNectria cinnabarina, die een verschillende mate van parasitisme vertoonden, waren ook in andere kenmerken onderscheidbaar, bijvoor beeld: Het mycelium groeide langzamer, soms kraakbeenachtig van uiterlijk. Soms had het een afwijkende rood-bruine kleur. Soms ook verloor het mycelium het vermogen om sporen te vormen. In de meeste gevallen vormde het geen peritheciën.

10. De stromata, waaruit zich later peritheciën ontwikkelden, vormden zich bij voorkeur na het afsterven van hout met sappige bast, op beschad uwde, vochtige plaatsen. Deze stromata waren donkerrood, geheel afwijkend van de normale tubercularia-vorm. Zij ontstonden in de zomer, en de peritheciën ontstonden daarop óók al grotendeels in de zomer. Soms ging de vorming der peritheciën nog wat langer door. Op de stromata konden zich ook sporodochia vormen, doch omgekkerd vormden zich nooit peritheciën buiten de voor hen karakteristieke donkerrode stromata. (Dus nooit op de stromata der sporodochiën, zoals men in de literatuur vindt vermeld.)

11. In de practijk worden de in het voorjaar gemaakte snoeiwonden, waarop zich bloedingsvocht bevindt, gemakkelijk doorNectria cinnabarina geïnfecteerd. Het snoeien met messen waarmede ook met sporodochia bezette takjes zijn afgesneden, kan de sporen in de wonden brengen. Het ontsmetten der messen na elke snede, en het snoeien in de zomer (Augustus), benevens het opruimen van met sporodochia bedekt hout, is daarom wenselijk, ongewenst daarentegen is het „uitsnijden” van schorsbrandplekken („kankers”) en het terugsnoeien van instervende takken.

Summary

In the Phytopathological laboratory, „Willie Commelin Scholten” at Baarn, research work was done from 1937 till 1939, and in 1946, concerning the parasitism ofNectria cinnabarina (Tode)Fr.

1. The inoculation of pruning wounds on a number of different trees and shrubs with mycelium ofNectria cinnabarina cultivated on cherry agar causes an increasing die-back of branches. The mycelium continues to be parasitic in the young, wide wood vessels.

2. With inoculations of short branches or stumps of branches in a smaller number of cases a burn in the bark is formed at the base of the branch stump or round the wound. This may be the case in pruning deeply. Deep incisions through the bark, touching the wood, have the same result. The burn is the result of an affection of the underlying wood. It is smaller than the discouloured and infected wood zone. The latter often extends far into the trunk, in particular into the older annual rings. This form of inoculation too leads in some cases to the die-back of branches and of the top of the tree.

3. The experiments show that in general the infections are most successful after the winter-rest period has elapsed, but that also in the other seasons (at the time of rich foliage least clearly however) the infections may appear.

4. The virulence of the cultures ofNectria cinnabarina used appears to vary considerably. In case of prolonged cultivation of the mycelia on artificial media they lose their virulence. In all probability this is also the case with theNectria cinnabarina which often lives saprophytically in nature.

5. When experimenting with the same virulent culture, it appears that the susceptibility of branches to the disease, is dependent on various factors:

-

a.

There are more and less susceptible species of trees; and also in closely related trees differences appear.

-

b.

The degree of susceptibility to infection in a certain species of tree varies with the seasons. Probably chiefly the woodvessels, and the enzymes which affect their formation, play a part here.

-

c.

Thick branches and trunks, once affected from the top down-wards waste away faster than thin, annual or bi-annual branches.

-

d.

Newly transplanted trees are less susceptible to infection (in case of artificial inoculation) than resident ones. Within certain limits rootpruning as well as shadow served as a protection.

6. Many species of trees react on the presence ofNectria cinnabarina in their woodvessels (in a zone of their wood into which it has not yet penetrated), in a very characteristic way. The following reactions were observed: Discoloration of the middle lamellae of the vessels, followed by that of the fibres and the secondary walls; the formation of gum in the vessels, of the same colour; the formation of tyloses in the vessels, till the protective-or woundtissue is formed; the formation of lacunar vessels, between the pithrays, which appear in the peach and the elm; swellings of the bark parenchyma; the formation of secondary cambia, shutting the wounds off from the outside with sound new tissue.

7. Branches, which do not yet show any of the phenomena mentioned in 6, but which wilt all the same, become fresh again when cut off and put in water. Apparently there were no toxins and the like present to cause the wilting but this had resulted from the cutting off of the watersupply by the formation of impenetrable „protective wood”.

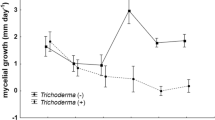

8. In fluid media in which mycelium ofNectria cinnabarina grows, a substance, proof against boiling, is formed, which has a growth-inhibiting effect onPythium de Baryanum Hesse. The strongest parasitic mycelia formed the strongest growth-preventing substance within the shortest time (six days).

9. Forms ofNectria cinnabarina, showing a different degree of parasitism, could also be differentiated by other characteristics; e.g. the mycelium grew more slowly, and was sometimes cartiligious in appearance. Sometimes it had an unusual reddish-brown colour. Sometimes also the mycelium lost the ability to form spores. In most cases it did not form any perithecia.

10. The stromata, from which later perithecia developed, formed by preference after the dying off of wood with a juicy bark, in shadowy, damp places. These stromata were of a dark red colour, quite different from the normal tubercularoid form. They came into existence in summer, and for the greater part the perithecia on them were also already formed in summer. Sometimes the formation of the perithecia continued somewhat longer. On the stromata sporodochia might also be formed, but on the contrary perithecia were never formed otherwise than from the dark red coloured stromata characteristic for them. (Never on the stromata of the sporodochia, as one finds mentioned in the literature.)

11. In practice the pruning wounds made in spring, on which bleedingsap is found, are easily infected byNectria cinnabarina. Pruning with infected knives may be the cause of spores entering the wounds. The disinfecting of the knives after each cut, and pruning in summer (August), besides the removal of wood covered with sporodochia is therefore desirable; inadvisable on the contrary is the „cutting out” of crustaceous cancers and the cutting back of wilting branches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lijst Van Geraadpleegde Literatuur

Admiraal, K. Mz., De kankerziekte der boomen. Amsterdam, M. M. Olivier, 1908.

Bartlett, J., Tree Research Laboratories. Bulletin no 2, 1937, Stamford Connecticut.

Bavendamm, Dr phil.Werner, Neue Untersuchungen über die Lebensbedingungen holzzerstörender Pilze, ein Beitrag zur Frage der Krankheitsempfänglichkeit unserer Holzpflanzen. Ber. deutsche botan. Gesellschaft, 1927, Bd. 35, H. 6; Zentralblatt f. Bacteriologie, 1928, Abt. II, Bd. 75 u. 76. Verlag Gustav Fischer, Jena, 1928.

Beck, R. Dr., Beiträge zur Morphologie und Biologie der förstlich wichtigen Nectria-Arten, insbesondere der Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. Tharandter forstliches Jahrbuch, Bd. 52, 161, 1902.

Behrens, Dr J., Phytopathologische Notizen. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenkrankheiten, 1895: 193.

Beyerinck, M. W. andA. Rant, Wundreiz, Parasitismus und Gummifluss bei den Amygdaleen. Centralblatt für Bact. Parasitenkunde u. Inf. krankheiten, Abt. II, Bd. 15: 366, 1906.

Boyce, J. S., Forest Pathology, 1938, p. 327.

Braun, Armin C., Beiträge zur Frage der Toxinbildung durch Pseudomonas tabaci (Wo. et Fo.) Stapp. Zentralbl. f. Bact. II, 97: 167–193, 1938.

—————, A comparative study of Bacterium tabacum Wolf and Foster, and Bacterium angulatum Fromme and Murray. Phytopathology 27: 283–304, 1937.

Brick, Dr C., Ueber Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. Jahrb. Hamb. wissensch., Anstalten, 10–2, 1892.

Broekhuizen, Simon, Wondreacties van hout, het ontstaan van thyllen en wondgom, in het bijzonder in verband met de iepenziekte. Diss. Utrecht, 1929.

Broek, M. v. d. enP. J. Schenk, Ziekten en beschadigingen der tuinbouwgewassen. Deel 1, 2de druk, p. 333, 1918.

Brown, W. Studies in the genus Fusarium VI, Annals of Botany 42, January 1928.

Büsgen, Dr Prof. M., Bau und Leben unserer Waldbäume. 3. Ausgabe, bearbeitet von E. Münch, 1927.

Carter, J. C., Tubercularia canker and Dieback of Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila L.). Phytopathology 37: 243, 1947.

Cook, M. T., A Nectria parasitic on Norway Maple. Phytopathology 7: 313–314, 1917.

-----, The diseases of tropical plants, p. 183, 1913.

Duggar, B. M., Fungous diseases of plants. A. cancer of woody plants, p. 239, 1909.

Durand, E. J., A disease of currant-canes. Cornell Univ. Agricultural Exper. Station, 125, 23–38, 1897.

Fischer, Prof. DrEd., und Prof. DrErnst gaumann, Biologie der pflanzenbewohnenden parasitischen Pilze, 1929.

Frank, Prof. Dr A. B., Die Krankheiten der Pflanzen, 1895.

Frank, A. B., Ueber die Gummibildung im Holze und deren physiologische Bedeutung. Ber. d. deutschen Bot. Ges. 2: 321, 1884.

Hartig, Prof. DrRobert, Lehrbuch der Baumkrankheiten, p. 94, 2de utigave, 1889.

Herse, F., Beitraege zur Kenntnis der histologischen Erscheinungen bei der Veredlung der Obstbäume. Landwirtsch. Jahrbuecher 37, Ergänzungsband 4: 71, 1908.

Hesler, L. R. andH. H. Whetzel, Manual of plant diseases, p. 210, 1917.

Hursh, C. R., The reaction of plant-stems to fungous products. Phytopathology 18: 603, 1928.

Iwanoff, K. S., Die im Sommer bei Petersburg (Russland) beobachteten Krankheiten. Zeitschr. f. Pflanzenkr. 10: 97–102, 1900.

Jackes, J. E., Un chancre de l’Orme de Sibérie (Ulmus pumila) causé par Nectria cinnabarina. Ann. Ass. canad.-francais., Sci., X p. 89, 1944.

Karmarkar, D. V., The seasonal cycles of nitrogenous and carbohydrate materials in fruit trees. Journal of pomology and horticultural science 12: 177, 1934.

Koch, L. W., Investigations on black knot of plums and cherries (Dibotrion morbosum). Scientific agriculture 15: 80, 1934.

Kivilaan, A., On the occurrence of, and prevention from the apple-tree canker, Nectria galligena Bres., in South-Estonia. Phytopathological exp. Stat. of the university of Tartu in Estonia, Bulletin 32, 1935. (Ook in overdruk in Agronoomia, 10, 11, 12.)

Küster, E., Pathologische Pflanzenanatomie. Dritte Aufl., p. 121, 1925.

Laubert, R., Die Rotpustelkrankheit (Nectria cinnabarina) der Bäume und ihre Bekämpfung. Kaiserl. biol. Anstalt f. Land- u. Forstwirtschaft, Flugblatt 25, 1905.

Line, J., The parasitism of Nectria cinnabarina (Coral spot), with special reference to its action on red currant. Transactions British Mycological Society 7: 1923.

Lohman, Marion, Watson, Alice J., Identity and host relations of Nectria species associated with diseases of hardwoods in the Eastern States. Lloydia VI, 2: 77, 1943.

Lohse, R., Entwurf einer Kritik der Thyllenfrage, mit Ergebnissen eigener Versuche. Botanisches Archiv. 5: 345, 1924.

Luijk, A. van, Antagonisme tusschen micro-organismen. Vakblad v. Biologen XX, 10: 177, 1939.

Mangin, L., Sur la Maladie du Rouge dans les pépinières et les Plantations de Paris. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Academie des Sciences 119: 753, 1894.

Mayr, H., Ueber den Parasitismus von Nectria cinnabarina. Untersuchungen aus dem forstbotanischen Institut zu Muenchen, 1882.

Morquer, M. etJ. Dufrenoy, Contribution à l’étude de la Gélification de la menbrane lignifiee chez le Chataignier. Comptes rendus Acad. Sciences Paris 173: 1012, 1921.

Münch, E., Untersuchungen über Immunität und Krankheitsempfänglichkeit der Holzpflanzen. Naturwissensch. Zeitschr. f. Forst- u. Landwirtschaft.: 135, 1909.

-----, Versuche über Baumkrankheiten. Ebenda: 389, 425, 1910.

Neger, F. W., Ber. d. Deutschen bot. Ges. 40: 306–313, 1921.

Otto, K. F., Zum Ahornsterben in der Baumschule (Nectria cinnabarina). Der Blumen u. Pfianzenbau 40. 1939

Petch, T., Tubercularia. Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. XXIV, 1940, p. 33.

Prillieux, Ed., Etudes sur la formation de la gomme dans les arbres fruitiers. Annales des sciences naturelles. Série 6, Botanique, 1: 176, 1875.

Radulescu, Th., Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Baumkrankheiten, zweiter Teil, Versuche über das Ulmensterben. Forstwissenschaftl. Centralblatt 59: 629–643, 1937.

Rant, A., De Gummosis der Amygdalaceae. Dissertatie Delft 1906.

Ritzema Bos, Prof. Dr J., Ziekten en beschadigingen der ooftboomen, 1905.

Rostrup, E., Undersogelser over Smyltesvampes paa Skovträr, ref. Bot. Zentralblatt 3: 355, 1890.

Schaffnit, E. u.M. Ludtke, Ueber die Bildung von Toxinen durch verschiedene Pflanzenparasiten. Ber. d. Deutschen Bot. Ges. 50: 1932.

Schellenberg, H. C., Untersuchungen über das Verhalten einiger Pilze gegen Hemizellulosen. Flora 98: 257–308, 1903.

Smyth, Elsie S., The seasonal cycles of nitrogenous and carbohydrate materials in fruit trees. The journal of Pomology and horticultural science, 12: 249, 1934.

Spierenburg, Dina, Bestrijding van het “Vuur” in Eschdoorns. Tijdschrift over Plantenziekten, 43: 150, 1937.

Stakman, E. C. andA. G. Tolaas, Fruit and vegetable diseases and their control. University of Minnesota, 1916.

Straszburger, Prof.Eduard, Ueber den Bau und die Verrichtungen der Leitungsbahnen in den Pflanzen, p. 510, 1891.

Temme, F., Ueber Schutz- und Kernholz, seine Bildung und seine physiologische Bedeutung. Landwirtschaftliche Jahrbücher, 16: 465, 1885.

Thomas, H. E., andA. B. Burrell, A twig canker of apple, caused by Nectria cinnabarina. Phytopathology, 19: 1125–1128, 1929.

Tyler, Parker andPope, Relation of wounds to infection of American elm by Cerastostomelle Ulmi and the occurrence of spores in rainwater. Phytopathology 30: 29–41, 1940.

Vaidya, V. G., The seasonal cycles of ash, carbohydrate and nitrogenous constituents in the terminal shoots of apple trees and the effects of five vegetatively propagated root-stocks on them. Journal of Pomology and Horticultural Science, 16: 101, 1938 (z. o. blz. 185).

Vloten, H. van, Een en ander over Mycologie en Boschbouw. Nederlandsch Bosch bouwtijdschrift, 6: 5–9, 1933.

—————, Verschillen in virulentie bij Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. Tijdschrift over Plantenziekten 49: 163–171, 1943.

Waksman, Selman A., Associative and antagonistic effects of microorganisms. Soil Science, New Jersey Agricultural experiment Station 43: 51, 1937.

Wagner, G., Ueber die Verbreitung der Pilze durch Schnecken. Zeitschrft. f. Pflanzenkrankheiten 6: 144–150, 1896.

Wehmer, C., Zum Parasitismus von Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. Zeitschrift f. Pflanzenkrankheiten 4: 74, 1894 en 5: 268, 1895.

Went, Joh.a C., Invuren van Iepen, veroorzaakt door Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. Tijdschrift over Plantenziekten 46: 212–115, 1904.

-----, Inoculatie van iepen met Nectria cinnabarina. Verslag v. d. Onderzoek. ged. 1943 over de Iepenziekte, Med. no 39 v. h. Comité B. en B. v. d. Iepenziekte, 1943, p. 14.

-----, Inoculatie van iepen met Nectria cinnabarina. Verslag v. d. Onderzoek. over de iepenziekte, verricht ged. 1943. Med. no 40 v. h. Comité B. en B. v. d. Iepenziekte, 1944, p. 4, 11–13.

-----, Inoculatie van Iepen met Nectria cinnabarina. Verslagen over 1944 en 1945. Med. no 41 v. h. Comité B. en B. v. d. ziekten in Iepen en andere boomsoorten, 1946, p. 22 en 23.

Werner, Carl, Die Bedingungen der Konidienbildung bei einigen Pilzen. Diss. Frankfurt a. M., 1898.

Westerdijk, Joh. enChristine Buisman, De Iepenziekte. Uitg. van de Ned. Heidemaatschappij, Arnhem, 1929.

Westerdijk, Joh. enA. van Luijk, Untersuchungen über Nectria coccinea (Pers.) Fr. und Nectria galligena. Med. Phytopathologisch Lab. Willie Commelin Scholten, Amsterdam, 6: 3–30, 1924.

Wieler, A., Ueber den Antheil des secundairen Holzes der dicotyledonen Gewächse an der Saftleitung und u.s.w. Pringsheim. Jahrb. für wissenschaftliche Botanik, 19, 82, 1888.

Will, Alfred, Beiträge zur Kenntnis von Kern- und Wundholz. Diss. Bern, 1899.

Wiltshire, S. P., Studies on the apple canker fungus. Annals of applied Biology 8: 182–192, 1921.

Winkler, H., Ueber einen neuen Thyllentypus, nebst Bemerkungen über die Ursachen der Thyllenbildung. Annales Jard. bot. Buitenzorg, 20: 19, 1906.

Winter, G., Einige Mitteilungen über die Schnelligkeit der Keimung der Pilzsporen und des Wachstums ihrer Keimschläuche. Hedwigian, 49–59, 1879.

Wollenweber, H. W., Pyrenomycetenstudien. Angewandte Botanik, Zeitschrift für Erforschung der Nutzpflanzen, 6: 1924.

-----, Hypocreaceae. Handbuch de Pflanzenkrankheiten, 542–575, 1928.

Wollenweber, H. W. undK. Röder, Das Verhalten einer Pfropfulme (Ulmus pumila) gegen Graphium ulmi. Nachrichtenblatt für den deutschen Pflanzenschutzdienst 4, 1938.

Zeller, S. M., Species of Nectria, Gibberella, Fusarium, Cylindrocarpon and Ramularia occurring in the bark of Pyrus spp. in Oregon. Phytopathology 16: 623–627, 1926.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Ontvangen voor publicatie November 1947

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uri, J. Het Parasitisme Van Nectria Cinnabarina (Tode) Fr.. Tijdschrift Over Plantenziekten 54, 29–73 (1948). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02651203

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02651203