Abstract

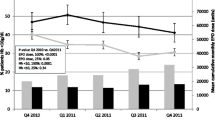

The authors describe and empirically demonstrate a form of bias that results from deriving subjects for clinical studies from available patients currently being followed in specific disease clinics instead of inception cohorts (patients enrolled at a uniform and early point in their disease). They label this effect “clinic patient bias.” It is a variation of prevalence-incidence (Neyman) bias in that it also results from the time gap between the onset of a specific characteristic (a risk factor, exposure or disease) and enrollment in the study, causing selective exclusion of fatal or short episodes, or mild or silent cases. Clinic patient bias may distort an estimate of relative risk in either direction. The empirical example is derived from a study of risk factors for developing complications such as peritonitis among end-stage renal disease patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). The use of available clinic patients rather than an inception cohort (patients newly beginning CAPD) resulted in the demonstration of false apparent risk relationships for two variables: the calendar date when patients began CAPD (with those enrolled at an earlier time appearing to be at lower risk), and serum albumin level at the start of CAPD (with those having lower albumin levels appearing to be at higher risk). This example demonstrates one of the potential hazards of using active or available clinic patients as a source of subjects for clinical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sackett DL. Bias in analytical research. J Chronic Dis 1979;32:51–63

Roberts R, Spitzer WO, Delmore T, Sackett DL. An empirical demonstration of Berkson’s bias. J Chronic Dis 1978;31:119–28

Neyman J. Statistics—servant of all sciences. Science 1955;122:401–7

Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Tugwell PX. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985

Corey PN, Steele C. Risk factors associated with time to first infection and time to failure on CAPD. Peritoneal Dialysis Bull 1983;Suppl:S14–7

Simpson EH. The interpretation of interaction in contingency tables. J R Statistical Soc 1951; Series B 13:238–41

Friedman GD, Kannel WB, Dawber TR, McNamara PM. Comparison of prevalence, case history and incidence data in assessing the potency of risk factors in coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 1966;83:366–78

Merrell M, Shulman LE. Determination of prognosis in chronic disease, illustrated by systemic lupus erythematosus. J Chronic Dis 1955;1:12–32

Wilson PWF, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Postmenopausal estrogen use. cigarette smoking, and cardiovascular morbidity in women over 30. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1038–43

Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective study of postmenopausal estrogen therapy and coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1044–9

Bailar JC. When research results are in conflict. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1080–1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Received from the Departments of Health Administration, Medicine and Preventive Medicine, and Biostatistics, University of Toronto: and the Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology. Nephrology, and Gastroenterology, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Supported by the National Health Research and Development Programme (Canada) through a project grant (6606-2362-42) and a National Health Research Scholar Award to Dr. Detsky.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Detsky, A.S., O’Rourke, K., Corey, P.N. et al. The hazards of using active clinic patients as a source of subjects for clinical studies. J Gen Intern Med 3, 260–266 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02596342

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02596342