Abstract

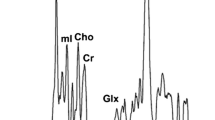

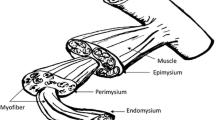

Magnetic resonance techniques afford a significant advantage for noninvasive diagnosis of cardiovascular pathology. The purpose of our present study was to assay the proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) sensitivity in the differential diagnosis of certain endocrine cardiovascular complications. In this context, we investigated the water state and content in the hypertrophied myocardium. Male and female Wistar rats were treated with different hormones (hydrocortisone acetate, testosterone, estradiol, thyroid hormones) in combination with isoproterenol (a synthetic catecholamine that induces myocardial ischemia and hypertrophy). The animals were sacrificed after 20 days of treatment and samples of integral myocardium and left ventricular myocardium were analyzed on a1H-NMR AREMI spectrometer (0.6 T; proton resonance at 25 MHz). The estimation ofT 2 was made by Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill pulse sequence. The data were fitted to a bi-exponential curve, yielding short (T 21) values forbound water and long (T 22) values forfree water. In order to evaluate the myocardial hypertrophy, the following ratios were calculated: integral myocardium to body weight; left ventricle to body weight; left ventricle to integral myocardium. The first two ratios were also calculated for dried tissue, in order to estimate its contribution to myocardial hypertrophy. Our findings demonstrate that myocardial hypertrophy is associated with a decrease ofT 22, as a consequence of the increase in the dried component (i.e. proteins) of the tissue, while the total tissue, while the total tissue water (H2Ot%, measured by gravimetry) was not significantly modified. Nevertheless, it is reasonable that the increase in the protein content would be proportional with the increase in H2Ot%. The decrease ofT 21 seems to be proportional with the level of left ventricle hypertrophy in female groups. The1H-NMR measurements were much sensitive for the differential diagnosis of myocardial hypertrophy in the case of left ventricle.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brent GA. The molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. N Engl J Med 1994;331:847–53.

Bristow MR, Minobe WA, Raynolds MV, Port JD, Rasmussen R, Ray PE, Feldman AM. Reduced beta 1 receptor messenger RNA abundance in the failing human heart. J Clin Invest 1993;92:2737–45.

Cappeli V, Moggio R, Polla B, Bottinelli R, Poggesi C, Reggiani C. The dual effect of thyroid hormones on contractile properties of rat myocardium. Pflügers Arch 1988:411:620–7.

Gherasim L. Medicina Interna, vol. 2. Bucuresti: Editura Medicala, 1996.

Hamilton MA. Prevalence and clincial implications of abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism in advanced heart failure. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:48–52.

Kaplan JR, Pettersson K, Manuck SB, Olsson G. Role of sympathoadrenal medullary activation in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Circulation 1991;84:23–32.

Lapidus L, Lindstedt G, Lundberg P-A, Bengisson C, Gredmark T. Concentrations of sex-hormone binding globulin in serum in relation to cardiovascular risk factors and to 12-year incidence of cardiovascular disease and overall mortality in postmenopausal women. Clin Chem 1986;32(1):146–152.

Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Stiles GL. Mechanisms of membrane-receptor regulation: biochemical, physiological, and clinical insights derived from studies of the adrenergic receptors. N Engl J Med 1984;310(24):1570–9.

Paun R. Tratat de Medicina Interna Partea a IV-a. Bucuresti: Editura Medicala, 1994.

Bottomley PA, Foster TH, Argesinger RE, Pfeifer LM. A review of normal tissue hydrogen NMR relaxation times and relaxation mechanisms from 1–100 MHz: dependence on tissue type, NMR frequency, temperature, species, excizion, and age. Med Phys 1988;11:425–59.

Cottin Y, Maupoil V, Mezeray C, Brunotte F, Rochette L Magnetic resonance relaxation times in ventricular hypertrophy induced by myocardial infarction in the rat. Cardioscience 1995;6:39–45.

Brown JJ, Peck WW, Gerber KH, Higgins CB, Strich G, Slutsky RA. Nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of acute and chronic myocardial infarction in dogs: alterations in spin-lattice relaxation times. Am Heart J 1984;108:1292–1297.

Been M, Smith MA, Ridgway JP, Douglas RHB, de Bono DP, Best JJK, Muir AL. Serial changes in theT 1 magnetic relaxation parameter after myocardial infarction in man. Br Heart J 1988;59:1–8.

Balta N, Stoian Gh, Boca A, et al. Biochemical and histo-enzymological investigations of the myocardium and coronary system in assessing experimental cardiac hypertrophy. J Med Biochem 1997;1(3):161–82.

Rüegg JC. Calcium in muscle activation. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1988.

Matsui S, Matsumori A, Sasayama S. Metabolism of failing myocardium. Nippon Rinsho 1993;51(5):1198–202.

Fried R, Boxt LM, Huber DJ, Reid LM, Adams DF. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of rat ventricles following chronic hypoxia: a model of right ventricular hypertrophy. Magn Reson Imag 1985;3:353–7.

Michel JB, Lattion AL, Salzmann JL, et al. Hormonal and cardiac effects of converting enzyme inhibition in rat myocardial infarction. Circ Res 1988;62:641–50.

Dumitru IF, Balta N, Burtea C, Stoian Gh, Petec Gh. The protective role of thiamine associated with medicinal products based on biogenic amines and the metabolic modifications made evident by1H-NMR. Roum Biotechnol Lett 1996;1(3):171–80.

Perin A, Sessa A, Diesiderio A. Polyamine levels and diamine oxidase activity in hypertrophic heart of spontaneously hypertensive rats and rats treated with isoproterenol. Biochem Biophys Acta 1983;755:344–51.

Shimizu M, Sasaki H, Sanyo J, Ogava K, Mizokami T, Yagi T, Kato H, Hamaya K, Namiki H, Isogui Y. Effect of captopril on isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy and polyamine contents. Jpn Circ J 1992;56:1130–7.

Stanton H, Brenner G, Mayfield ED. Studies on isoproterenol-induced cardiomegaly in rats. Am Heart J 1992;77:72–80.

Gillis P, Peto S, Muller RN. Bound water in heterogenous system relaxometry: an ill-defined concept. Magn Reson Imag 1991;9:703–8.

Barsky D, Putz B, Schulten K. Theory of heterogenous relaxation in compartmentalized tissues Magn Reson Med 1997;37:666–75.

Bronskill MJ, Santyr GE, Walters B, Henkelman RM. Analysis of discreteT 2 components of NMR relaxation for aqueous solutions in hallow capillaries. Magn Reson Med 1994;31:611–8.

Coolbaugh Lester C, Bryant RG. Water-proton nuclear magnetic relaxation in heterogenous systems: hydrated Iysozyme results. Magn Reson Med 1991;22:143–53.

Fung BM, Puon PS. Nuclear magnetic resonance transverse relaxation in muscle water. Biophys J 1981;33:27–38.

Iino M. Dynamic properties of bound water studied through macroscopic water relaxations in concentrated protein solutions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1994;1208:81–8.

Watanabe T, Murase N, Staemmler M, Gersonde K. Multiexponential proton relaxation processes of compartimentalized water in gels. Magn Reson Med 1992;27:118–34.

Akber SF. NMR relaxation data of water proton in normal tissues. Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR 1996;28(4):205–38.

Rofstad EK, Steinsland E, Kaalhus O, Chang YB, Høvik B, Lyng H. Magnetic resonance imaging of human melanoma xenografts in vivo: proton spin-lattice and spin-spin relaxation times versus fractional tumor water content and fraction of necrotic tumor tissue. Int J Radiat Biol 1994;65(3):387–402.

Shioya S, Tsuji C, Kurita D, Katoh H, Tsuda M, Haida M, Kawana A, Ohta Y. Early damage to lung tissue after irradiation detected by the magnetic resonanceT 2 relaxation time. Radiat Res 1997;148(4):359–64.

Hill MF, Singal PK: Right and left myocardial antioxidant responses during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction. Circulation 1997;96(7):2414–20.

Manolis AJ, Beldekos D, Hatzissavas J et al. Hemodynamic and humoral correlates in essential hypertension: relationship between patterns of left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial ischemia. Hypertension 1997;30(3):730–4.

Burtea C, Mateescu C. The usefulness of1H and23Na NMR spectrometry in the study of muscle contraction and of myopathic alteration. An approach of the influence of proteins and ions onT 2 in muscle tissue. MAGMA Suppl 1997;5(2):153.

gatina R, Botea S, Mocanu M. Changes in proton transverse relaxation times of rat myocardium that has suffered a previous oxidative insult. MAGMA 1997;5(3):223–30.

Ling GN. A quantitative theory of solute distribution in cell water according to molecular size. Physiol Chem Med NMR 1993;25(3):145–75.

Maxwell SRJ, Lip GYH. Free radicals and antioxidants in cardiovascular disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;44(4):307–17.

Perkins WJ, Han YS, Sieck GC. Skeletal muscle force and actomyosin ATPase activity reduced by nitric oxide donor. J Appl Physiol 1997;83(4):1326–32.

Pompella A. Biochemistry and histochemistry of oxidant stress and lipid peroxidation. Int J Vitamin Nutr Res 1997;67(5):289–97.

Uchida K, Sakai K, Itakura K, Osawa T, Toyokuni S. Protein modification by lipid peroxidation products: Formation of malondialdehyde-derived N episoln-(2-propenal)lysine, in proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 1997;346(1):45–52.

McManus BM, Davies MJ. In: Damjanov I, Linder J, editors. Anderson's Pathology, Part 4, Chap 45, vol. 1, 10th edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996.

Ljubuncic P, Mujic F, Winterhalter M, Hukovic N, Vidovic Z, Duricic S. Isoproterenol toxicity in the myocardium in an experiment. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 1992;43(1):11–20.

Cosmas AC, Kerman K, Buck E, Fernhall B, Manfredi TG. Exercise and dietary cholesterol alter rat myocardial capillary ultrastructure. Eur J Appl Physiol 1997;75(1):62–7.

Ljungqvist A, Unge G. Capillary proliferative activity in myocardium and skeletal muscle of exercised rats J Appl Physiol 1977;43(2):306–7.

Mattfeldt T, Kramer KL, Zeitz R, Mall G. Stereology of myocardial hypertrophy induced by physical exercise. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1986;409(4):473–84.

Qu X. Morphological study of myocardial capillaries in endurance trained rats. Br J Sports Med 1990;24(2):113–6.

McKirnan MD, Bloor CM. Clinical significance of coronary vascular adaptations to exercise training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994;26(10):1262–8.

Scheuer J. Effects of physical training on myocardial vascularity and perfusion. Circulation 1982;66(3):491–5.

Dammrich J, Pfeifer U. Cardiac hypertrophy in rats after supravalvular aortic constriction. I. Size and number of cardiomyocytes, endothelial and interstitial cells. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 1983;43(3):265–86.

Wachtlova M, Ostadal B, Mares V. Thyroxine-induced cardiomegaly in rats of different age. Physiol Bohemoslov 1985;34(5):385–94.

Anversa P, Melissari M, Beghi C, Olivetti G. Structural compensatory mechanisms in rat heart in early spontaneous hypertension. Am J Physiol 1984;246:H739–46.

Milcu SM. Tratat de Endocrinologie Clinica, vol. 1. Bucuresti: Editura Academiei Romane, 1992.

Florini JR. Hormonal control of muscle growth. Muscle Nerve 1987;10:577–98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burtea, C., Gatina, R., Stoian, G. et al. Spin-spin relaxation times in myocardial hypertrophy induced by endocrine agents in rat. MAGMA 7, 184–198 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02591336

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02591336