Abstract

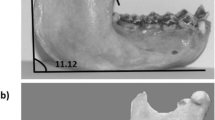

This study was carried out on 56 mandibles belonging to skeletal remains recovered from archaeological excavations in Israel dated to 6.000 BP. or less, 2 Neandertal mandibles dating between 50.000–60.000 BP. and 2 early H. sapiens sapiens mandibles both dating to circa 92.000 yr BP. Mandibular body length, the distance from the anterior border of the symphysis to a line bisecting the first molar (distance 1), and the distance from the line bisecting the first molar to the mandibular angle (distance 2) were measured. Distance 1, showed little variation between specimens. However, distance 2 showed a significant difference between sexes and between early and late specimens. For all specimens examined there was a low nonsignificant correlation, between the length of the mandible and distance 1, while there was a high correlation between the length of the mandibular body and distance 2. There was little or no correlation between distance 1 and 2. We propose that the human mandible, as a lever arm, can be divided into two functional parts; an anterior part which shows little change over the last 90000 years, and a posterior part which differs in accordance with the length of the mandibular corpus. These changes in distance 2 appear to correlate to changes in body size and diet, suggesting that as proposed by Hylander (1988) chewing rather than incision has played the main role in evolutionary trends of the hominid mandible. This is also in accordance with mandibular growth during development where the lengthening of the jaw takes place mostly in the posterior part by remodeling in the ramus area (Enlow, 1990) both during individual development (ontogenesis) and through evolutionary changes (phylogenesis).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brace C.L., 1979.Krapina, “Classic” Neanderthals, and the Evolution of European face. J. of Human Evolution, 8: 527–550.

Brose D.S., Wolpoff, M.H., 1971.Early upper Paleolithic man and late middle Paleolithic tools. Amer. Anthrop., 73: 1156–1194.

Campbell B.G., 1967.Human Evolution. Aladina publishing company, Chicago.

Dauphin C.M., 1979.Dor, Byzantine church. Israel Explor J., 29: 235–236.

Dauphin C.M., 1981.Dor, Byzantine church. Israel Explor J., 31: 117–119.

Dauphin C.M., 1984.Dor, Byzantine church. Israel Explor J., 34: 271–274.

Devlin H. & Wastell D.G., 1986.The mechanical advantage of biting with posterior teeth. J. Oral Rehabil., 13(6): 607–610.

Du Brul L.E., 1977.Early Hominid feeding mechanisms Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 47: 305–320.

Enlow D.H., 1979.Rotations of the mandible during growth.In:Determinants of Mandibular Form and Growth. ed: McNamara, J.A., JR. University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Enlow D.H., 1990. Facial growth. W.B. Saunders company, Philadelphia.

Eriksson P.O. & Thornell L.E., 1983.Histochemical and morphological muscle-fiber characteristics of the human masseter, the medial pterygoid and the temporal muscles. J. Oral Biol., 28: 781–795.

Frost H.M., 1985.The “new bone”; some anthropological potentials. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 28: 211–226.

Haskell B., Day M. & Tetz J., 1986.Computer-aided modelling in the assessment of the biomechanical determinants of diverse skeletal patterns. American J. of Orthodontics 89: 363–382.

Hylander W.L., 1975.The human mandible: lever or link? Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 43: 227–242.

Hylander W.L., 1988.Implications of in vivo experiments for interpretating the functional significance of “Robust” Australopithecine jaws. In Evolutionary History of tha “Robust” Australopithecines ed: Grine, F.E. Aldine de Gruyter, New York.

Kay R.F. & Hilemae K.M., 1974.Jaw movement and tooth use in recent and fossil primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 40: 227–256.

Lanyon L.E. & Rubin C.T., 1985.Functional adaptation in skeletal structures. in: Functional Vertebrate Morphology. ed: Hildebrand, M., Brandel, M.D., Lien, K.F., Woke, D.B., Harvard University Press, pp. 1–25.

Lapp P.W. & Lapp N.L., 1974.Discoveries in the Wadi ed-Daliyeh AASOR, XLI: 87–95.

Mansour R.M. & Revnik R.J., 1975.In vivo occlusal forces and moments: I. Forces measured in terminal hinge position and associated moments. J. Dent. Res., 54: 114–120.

Matthews B., 1975.Mastication. in: Applied Physiology of the Mouth. ed: Javelle, C., pp. 199–241.

McNamara J.A., Jr. 1981.Functional determinants of craniofacial size and shape. inCraniofacial Biology. ed: Carlson D.S. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

McCown T.D. & Keith A., 1939.The stone age of mount Carmel.In:the fossil Human remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Moss M.L., 1969.The primary role of functional matrices in facial growth. Am. J. Orthod., 55: 566.

Moscowitch M., Simkin A., Gomori J.M. & Smith P., 1992.The relations between external dimensions of the human mandibular geometry and cortical bone morphology as determined with the aid of CT scans: Some biomechanical interpretations. 3rd International Congress on Human Paleontology. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, Supplement 1, Book of Abstracts, pp. 85.

Moscowitch M., Simkin A., Gomori J.M., & Smith P., in press.The relation between external dimensions of the human mandible and cortical bone morphology as determined with the aid of CT scans. J. Human Evolution.

Pruim G.J., De Jongh H.J. & Bosch T., 1980.Forces acting on the mandible during bilateral static bite at different bite force levels. J. Biomechanics, 13: 755–763.

Smith P., 1982.Dental reduction: selection or drift? in:Teeth: Form, Function and Evolution. ed: Kurten, B., Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 366–379.

Smith P., 1982.The physical characteristics and biological affinities of the MB I skeletal remains from Jebel Qa' agir. BASOR, 245: 65–73.

Smith P. & Peretz B., 1986.Hypoplasia and health status: a comparison of two lifestyles. Human Evolution, 1: 535–544.

Suzuki H. & Takai F., 1970.The Amud Man and his Cave Site. Tokyo: Academic Press.

Throckmorton G.S., Finn R.A. & Bell W.H., 1980.Biomechanics of differences in lower facial height. American J. Orthod., 77: 410–420.

Vandermeersch B., 1981.Les hommes fossiles de Qafzeh (Israel). Cahiers de Paleontologie (Paleoanthropologie). Ed. du CNRS, Paris.

Wolpoff M.H., 1979.Some aspects of human mandibular evolution. In: Determinants of Mandibular Form and Growth. ed: Mcknamara J.A., The Univ. of Michigan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moskowitsch, M., Smith, P. A note on functional implications of morphological variation in the human mandible. Int. J. Anthropol. 8, 53–60 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02447644

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02447644