Abstract

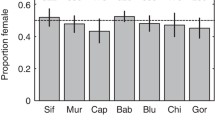

The reproductive data for Japanese monkeys,Macaca fuscata fuscata, which had been recorded for the 34 years from 1952 to 1986 on Koshima, were analyzed in terms of the influence of changes in artificial food supplies, the differences in reproductive success between females, the timing of births, and the secondary sex ratio. Koshima monkeys increased in number until 1971 when the population density was still small and artificial provisioning was copious. As described byMori (1979b), the severe reduction in artificial food supplies, which began in 1972, had an enormous deleterious effect on reproduction: the birth ratio of adult females of 5 years of age or more fell from 57% to 25%; the rate of infant mortality within 1 year of birth rose from 19% to 45%; primiparous age rose from 6 to 9 years old on average; and there was an increased death rate among adult and juvenile females. The prolonged influence of “starvation” may be seen in the significantly delayed first births of those females that were born just before the change in food supplies. When reproductive parameters are compared between the females who belonged to six lineages in the group during these periods, they were found to be rather consistent, although some individual differences can be recognized among females and subgroups. The apparent trend was that some of the most dominant females retained superior reproductive success while that of the second-ranked females has tended to diminish over the years since 1972. Such opposing trends were seen only in the most dominant lineage group and such a difference was not recognized among the females of other lineages. The difference in reproductive success is discussed in relation to both the different situations that arise because of the artificial food supplies and differences in feeding strategies. Multiparous females, after a sterile year, gave birth somewhat earlier than those who reared infants in the preceding year and, when artificial provisioning was intense, they tended to give birth a little earlier than during other periods. There is some evidence that the mortality of later-born infants was higher than that of earlier-born infants after 1972. However, this difference may not be responsible for the differential reproductive success of females since the timing of births did not differ among lineages. Furthermore, during the time when many females gave birth continuously, prior to 1972, the infant mortality did not differ with respect to the timing of births. The differences in infant mortality were not correlated with the reproductive history, parity or age of the mother, or with the sex of the infant. The secondary sex ratio varied by only a small amount, from slightly male-biased ratio (114: 100) when correlated with reproductive history, parity, age of mother, sex and survival ratio for preceding infants, timing of birth, and lineage of the female. Furthermore, the change in artificial food supplies did not cause any modifications of the secondary sex ratios, despite its enormous deleterious effect on reproduction. The secondary sex ratio of Japanese monkeys may not be influenced by the social factors mentioned.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Altmann, J., 1980.Baboon Mothers and Infants. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Anderson, D. M. &M. J. A. Simpson, 1979. Breeding performance of a captive colony of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta).Lab. Anim., 13: 275–281.

Berman, C. &R. Rawlins, 1985. Maternal dominance, sex ratio and fecundity in one social group on Cayo Santiago.Amer. J. Primatol., 8: 332.

Clark, A. B., 1978. Sex ratio and local resource competition in a prosimian primates.Science, 201: 163–165.

Clutton-brock, T. H., 1982. Sons and daughters.Nature, 298: 11–12.

Darwin, C., 1871.The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Appleton, New York.

Dittus, W. P. J., 1977. The social regulation of population density and age-sex distribution in the toque monkey.Behaviour, 63: 281–322.

————, 1979. The evolution of behaviors regulating density and age-specific sex ratios in a primate population.Behaviour, 69: 265–302.

Drickamer, L. C., 1974. A ten-year summary of reproductive data for free-rangingMacaca mulatta.Folia Primatol., 21: 61–80.

Dunbar, R. I. M. &E. P. Dunbar, 1977. Dominance and reproductive success among female gelada baboons.Nature, 266: 351–352.

Fedigan, L. M., L. Fedigan, S. Gouzoules, H. Gouzoules, &N. Koyama, 1986. Lifetime reproductive success in female Japanese macaques.Folia Primatol., 47: 143–157.

Fukuda, F., 1988. Influence of artificial food supply on population parameters and dispersal in Hakone T troop of Japanese macaques.Primates, 29: 477–492.

Gouzoules, H., S. Gouzoules, &L. Fedigan, 1982. Behavioural dominance and reproductive success in female Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata).Anim. Behav., 30: 1138–1150.

Gray, J. P., 1985.Primate Sociobiology. HRAF Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Hamada, Y., M. Iwamoto, &T. Watanabe, 1986. Somatometrical features of Japanese monkeys in the Koshima Islet: in viewpoint of somatometry, growth, and sexual maturation.Primates, 27: 471–484.

Hamilton, W. J., III, 1985. Demographic consequences of a food and water shortage to desert chacma baboons,Papio ursinus.Int. J. Primatol., 6: 451–462.

Hasegawa, M., 1983.Yasei Nihonzaru no Ikuji Kohdoh (Nursing Behavior in Wild Japanese Monkeys). Kaimeisha, Tokyo. (in Japanese).

Horii, Y., I. Imada, T. Yanagida, M. Usui, &A. Mori, 1982. Parasite changes and their influence on the body weight of Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata fuscata) of the Koshima troop.Primates, 23: 416–431.

Imanishi, K., 1957. Identification: a process of socialization in the subhuman society ofMacaca fuscata.Primates, 1: 1–29. (in Japanese with English summary)

Itani J., 1972.Reichourui no Shakai Kouzou (The Social Structure of Primates). Kyoritsu-shuppan, Tokyo. (in Japanese)

———— &K. Tokuda, 1958.Koshima no Saru (Japanese Monkeys on Koshima Island). Kobunsha, Tokyo. (in Japanese)

————, ————,Y. Furuya, K. Kano, &Y. Shin, 1963. The social construction of natural troops of Japanese monkeys in Takasakiyama.Primates, 4(3): 1–42.

Itoigawa, N. &T. Minami, 1986. Changes of reproductive activity due to the ageing of females; focusing on the birth ratio. In:Comparative Ethology on the Development of Japanese Monkeys,N. Itoigawa (ed.), Faculty of Human Science, Osaka Univ., Osaka, pp. 52–57. (in Japanese)

Iwamoto, M. & A. Mori, 1978. Conservation of monkeys and nature of Koshima, for the adequate management. Koshima Lab., Primate Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ. (in Japanese)

Iwamoto, T., 1974. A bioeconomic study on a provisioned troop of Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata fuscata) at Koshima Islet, Miyazaki.Primates, 15: 241–262.

————, 1982. Food and nutritional condition of free-ranging Japanese monkeys on Koshima Islet during winter.Primates, 23: 153–170.

————, 1987. Feeding strategies of primates in relation to social status. In:Animal Societies; Theories and Facts,Y. Ito,J. L. Brown, &J. Kikkawa (eds.), Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, pp. 243–252.

Iwano, T., 1978. Crisis and protection of Japanese monkeys.Nihonzaru, 4: 122–131. (in Japanese)

Japanese Standard Association (ed.), 1972.Statistical Tables and Formulas with Computer Applications; JSA-1972. Japanese Standard Association, Tokyo.

Kawai, M., 1958a. On the rank system in a natural group of Japanese monkey (I) — the basic and the dependent rank.Primates, 1: 111–130. (in Japanese with English summary)

————, 1958b. On the rank system in a natural group of Japanese monkeys (II) — in what pattern does the ranking order appear on and near the test box.Primates, 1: 131–148. (in Japanese with English summary)

————, 1969.Nihonzaru no Seitai (Ecology of Japanese Monkeys) (2nd edn.). Kawade-shoboshinsha, Tokyo. (in Japanese)

————, 1974. Koshima field laboratory.Ann. Rec. Primat. Res. Inst., 4: 16–17. (in Japanese)

————,S. Azuma, &K. Yoshiba, 1967. Ecological studies of reproduction in Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata), I. Problems of the birth season.Primates, 8: 35–74.

Kawamura, S., 1956. Prehuman culture.Shizen, 11(11): 28–34. (in Japanese)

————, 1958. Matriarchal social ranks in the Minoo-B troop: a study of rank system of Japanese monkeys.Primates, 1: 149–156. (in Japanese with English summary)

Koyama, N., 1967. On dominance rank and kinship of a wild Japanese monkey troop in Arashiyama.Primates, 8: 189–216.

————, 1984. Population changes of Japanese monkeys in Arashiyama.Bull. Arashiyama Inst. Nat. Hist., 3: 30–38. (in Japanese)

————,K. Norikoshi, &T. Mano, 1975. Population dynamics of Japanese monkeys at Arashiyama. In:Contemporary Primatology,S. Kondo,M. Kawai, &A. Ehara (eds.), S. Karger, Basel, pp. 411–417.

Kudo, H., 1984. Dynamics of social relationships in the process of troop formation of Japanese monkeys in Koshima.J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon, 92: 253–272.

Maeda, Y. (ed.), 1967.Behavioral Studies of Japanese Monkeys: Focusing on the Wild Troop at Katsuyama, Okayama Prefecture. Osaka Univ., Osaka. (in Japanese)

Marushashi, T., 1980. Feeding behavior and diet of the Japanese monkey (Macaca fuscata yakui) on Yakushima Island, Japan.Primates, 21: 141–160.

Meikle, D. B., B. L. Tilford, &S. H. Vessey, 1984. Dominance rank, secondary sex ratio, and reproduction of offspring in polygynous primates.Amer. Naturalist, 124: 173–188.

Mito, S., 1971.Koshima no Saru; 25nen no Kansatsu Kiroku (Japanese Monkeys in Koshima; Twenty Five Years of Observation). Popula-sha, Tokyo. (in Japanese)

Mori, A., 1979a. An experiment on the relation between the feeding speed and the caloric intake through leaf eating in Japanese monkeys.Primates, 20: 185–195.

————, 1979b. Analysis of population changes by measurement of body weight in the Koshima troop of Japanese monkeys.Primates, 20: 371–397.

————, 1979c. The role of sex as a centripetal factor in a Japanese monkey troop. In:Biosociological Studies on the Role of Sex in the Japanese Monkey Society, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto Univ., Inuyama, pp. 41–49. (in Japanese)

————,U. Mori, &T. Iwamoto, 1977. Changes in social rank among female Japanese monkeys living on Koshima Islet. In:Keishitsu, Shinka, Reichorui (Morphology, Evolution and Primates),T. Kato, S. Nakao, &T. Umesao (eds.), Chuokoron-sha, Tokyo, pp. 311–334. (in Japanese)

————,K. Watanabe, &N. Yamaguchi, 1989. Longitudinal changes of dominance rank among the females of the Koshima group of Japanese monkeys.Primates, 30: 147–173.

Noyes, M. J. S., 1982. The association of maternal attributes with infant gender in a group of Japanese monkeys.Int. J. Primatol., 3: 320.

Ohsawa H., Y. Sugiyama, &A. Nishimura, 1977. Population dynamics of Japanese monkeys at Takasakiyama by the marking trace. In:Takasakiyama Nihonzaru Chosa Hokoku; 1971–1976 (Population Dynamics of Japanese Monkeys at Takasakiyama — report of the investigation; 1971–1976), Oita City, Oita, pp. 19–36. (in Japanese)

Paul, A. &D. Thommen, 1984. Timing of birth, female reproductive success and infant sex ratio in semifree-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus).Folia Primatol., 42: 2–16.

Pianka, E. R., 1970. On r and K selection.Amer. Naturalist, 104: 592–597.

Rawlins, G. R. &M. J. Kessler, 1986. Secondary sex ratio variation in the Cayo Santiago macaque population.Amer. J. Primatol., 10: 9–23.

————, ———— &J. E. Turnquist, 1984. Reproductive performance, population dynamics and anthropometrics of the free-ranging Cayo Santiago rhesus macaques.J. Med. Primatol., 13: 247–259.

Sade, D. S., K. Cushing, P. Cushing, J. Danaif, A. Figueroa, J. R. Kaplan, C. Lauer, D. Rhodes, &J. Schneider, 1976. Population dynamics in relation to social structure on Cayo Santiago.Yearb. Phys. Anthropol., 20: 253–262.

Silk, J. B., C. B. Clark-Wheatley, P. S. Rodman, &A. Samuels, 1981. Differential reproductive success and facultative adjustment of sex ratios among female bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata).Anim. Behav., 29: 1106–1120.

Simpson, M. J. A. &A. E. Simpson, 1982. Birth sex ratios and social rank in rhesus monkey mothers.Nature, 300: 440–441.

Small, M. F. &D. G. Smith, 1985. Sex ratio of infants produced by male rhesus macaques.Amer. Naturalist, 126: 354–361.

———— &S. B. Hrdy, 1986. Secondary sex ratios by maternal rank, parity, and age in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mullata).Amer. J. Primatol., 11: 359–365.

Stern, C., 1973.Principles of Human Genetics. (3rd ed.), W. H. Freeman & Company, San Francisco.

Sugiyama, Y. &H. Ohsawa, 1982. Population dynamics of Japanese monkeys with special reference to the effect of artificial feeding.Folia Primatol., 39: 238–263.

Takizawa, H., 1983. On the genealogical table, the troop size, the number of infants and the survival rate of infants of Kamuri-A and -C Troop, that are wild Japanese monkey (Macaca fuscata) troop in Mt. Hakusan.Ann. Rep. Hakusan Nat. Conser. Center, 9: 67–76. (in Japanese with English summary)

Tokita, E. &S. Hara, 1975. Records of provisioning and behavioral observations of Japanese monkeys of Shiga-A troop.Seiri Seitai, 16: 24–33. (in Japanese)

Trivers, R. L., &D. E. Willard, 1973. Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring.Science, 179: 90–91.

Wilson, M. E., T. P. Gordon, &I. S. Bernstein, 1978. Timing of births and reproductive success in rhesus monkey social groups.J. Med. Primatol., 7: 202–212.

Wolfe, L., 1984. Female rank and reproductive success among Arashiyama B Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata).Int. J. Primatol., 5: 133–143.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, K., Mori, A. & Kawai, M. Characteristic features of the reproduction of Koshima monkeys,Macaca fuscata fuscata: A summary of thirty-four years of observation. Primates 33, 1–32 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02382760

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02382760