Abstract

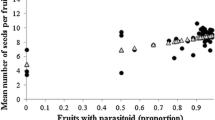

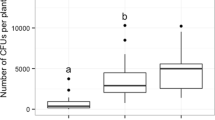

Cassava plants exude phloem saps at the base of the petioles of the youngest leaves. The effect of these nutrient-rich droplets on the interaction between the predatory miteTyphlodromalus limonicus and the herbivorous miteMononychellus tanajoa was investigated in a semi-field setting. These two organisms were chosen as a model system due to their strong association with cassava. The hypothesis that exudate production can be considered in terms of extrinsic defense was tested experimentally. Because non-producing clones could not be found exudate production was mimicked (or not) by applying honey droplets on the petioles of plants from which exuding plant parts were aborted. The experiments indicated that: (1) The presence of exudate on otherwise clean plants does not prevent extinction of the predator population, but the rate of population decrease is consistently lower than when no exudate is present. (2) When a second food source enables the predators to reproduce, higher population densities are always attained when the sugar source is also present. (3) Higher predator numbers invariably coincide with lower herbivore abundance. (4) Lower prey abundance does not lead to a reduction in egg production when honey is present. (5) Presence of honey leads to enhanced juvenile/adult survival or reduced emigration and thus to a higher number of female predators.

In interpreting the results careful attention was paid to the effect of cassava mildew because spores of this fungus were shown to be an adequate food alternative for the predator under study. The presence of this mildew (Oidium manihoti) hampered straightforward interpretation of some experiments but left the main conclusions unaltered.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

André, M., 1939. Sur les acarodomaties. Rev. Bot. Appl., 220: 835–847.

Badii, M.H. and McMurtry, J.A., 1983. Effect of different foods on development, reproduction and survival ofPhytoseiulus longipes [Acarina: Phytoseiidae]. Entomophaga, 28: 161–166.

Bakker, F.M. and Klein, M.E., 1990. The significance of cassava exudate for predaceous mites. Symp. Biol. Hung., 39: 437–439.

Bakker, F.M. and Oduor, G.I., 1991. How plants maintain body-guards: plant exudate as a food source for phytoseiid mites. In: R. Schuster and P.W. Murphy (Editors), The Acari, Reproduction, Development and Life History Strategies. Chapman-Hall, London, pp. 325.

Bellotti, A.C., Mesa, N.C., Serrano, M., Guerrero, J.M. and Herrera, C.J., 1987. Taxonomic inventory and survey activity for natural enemies of cassava green mites in the Americas. Insect Sci. Appl., 8: 845–849.

Belt, T., 1874. The Naturalist in Nicaragua. Murray, London.

Bentley, B.L., 1976. Plants bearing extrafloral nectaries and the associated ant community: interhabitat differences in the reduction of herbivore damage. Ecology, 57: 815–820.

Bentley, B.L., 1977a. Extrafloral nectaries and protection by pugnacious bodyguards. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 8: 407–427.

Bentley, B.L., 1977b. The protective function of ants visiting the extrafloral nectaries ofBixa orellana (Bixaceae). J. Ecol., 65: 27–38.

Braun, A.R., Mesa, N.C. and Bellotti, A.C., 1988. Life table analysis of tritrophic interactions: cassava,Mononychellus progresivus andTyphlodromalus limonicus. Proc. Brighton Crop Protection Conference, Vol. 9c(3): 1131–1135.

Chant, D.A., 1959. Phytoseiid mites (Acarina: Phytoseiidae). Part I. Bionomics of seven species in southeastern England. Part II. A taxonomic review of the family Phytoseiidae, with descriptions of thirty-eight new species. Can. Entomol., 91, Suppl. 12, 166 pp.

Chant, D.A. and Fleschner, C.A., 1960. Some observations on the ecology of phytoseiid mites (Acarina: Phytoseiidae) in California. Entomophaga, 5: 131–139.

Compton, S.G. and Robertson, H.G., 1988. Complex interactions between mutualisms: ants tending homopterans protect fig seeds and pollinators. Ecology, 69: 1302–1305.

de Moraes, G.J. and McMurtry, J.A., 1983. Phytoseiid mites (Acarina) from Northeastern Brazil with descriptions of four new species. Int. J. Acarol., 9: 131–148.

de Moraes, G.J. and Mesa, N.C., 1988. Mites of the family Phytoseiidae (Acari) in Colombia, with descriptions of three new species. Int. J. Acarol., 14: 71–88.

de Moraes, G.J., Denmark, H.A. and Guerrero, J.M., 1982. Phytoseiid mites of Colombia. Int. J. Acarol., 8: 15–22.

de Moraes, G.J., Mesa, N.C. and Reyes, J.A., 1988. Some phytoseiid mites from Paraguay with description of a new species. Int. J. Acarol., 14: 221–223.

de Moraes, G.J., Mesa, N.C. and Braun, A., 1991. Some phytoseiid mites of Latin America (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Int. J. Acarol., 17: 117–139.

Dicke, M. and Sabelis, M.W., 1988. How plants obtain predatory mites as bodyguards. Neth. J. Zool., 38: 148–165.

Dreisig, H., 1988. Foraging rate of ants collecting honeydew or extrafloral nectar, and some possible constrains. Ecol. Entomol., 13: 143–154.

El-Banhawy, E.M., 1975. Biology and feeding behaviour of the predatory mite,Amblyseius brazilii (Mesostigmata: Phytoseiidae). Entomophaga, 20: 353–360.

Ferragut, F., Garcia-Mari, F., Costa-Comelles, J. and Laborda, R., 1987. Influence of food and temperature on development and oviposition ofEuseius stipulatus andTyphlodromalus phialatus (Acarina: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 3: 317–329.

Hagen, K.S., 1986. Ecosystem analysis: Plant cultivars (HPR), entomophagous species and food supplements. In: D.J. Boethel and R.D. Eikenbary (Editors), Interactions of Plant Resistance and Parasitoids and Predators of Insects. John Wiley, New York, NY, pp. 151–197.

Herren, H.R. and Neuenschwander, P., 1991. Biological control of cassava pests in Africa. Ann. Rev. Entomol., 36: 257–283.

Hespenheide, H.A., 1985. Insect visitors to extrafloral nectaries ofByttneria aculeata (Sterculiaceae): relative importance and roles. Ecol. Entomol., 10: 191–204.

Hölldobler, B. and Wilson, E.O., 1990. The Ants. Springer, Berlin, 732 pp.

Hoy, M.A. and Smilanick, J.M., 1981. Non-random prey location by the phytoseiid predatorMetaseiulus occidentalis: differential responses to several spider mite species. Entomol. Exp. Appl., 29: 291–253.

Huxley, C.R., 1986. Evolution of benevolent ant-plant relationships. In: B. Juniper and Sir R. Southwood (Editors), Insects and the Plant Surface. Edward Arnold, London, pp. 257–282.

Inouye, D.W. and Taylor, O.R., 1977. An experimental investigation of a plant-ant-seed predator system from a high altitude temperate region. Ecology, 60: 1–7.

Jacobs, M., 1966. On domatia: the viewpoints and some facts I. Academie van Wetenschappen Amsterdam, 69: 275–316.

James, D.G., 1989. Influence of diet on development, survival and oviposition in an Australian phytoseiid,Amblyseius victoriensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 6: 1–10.

Janzen, D.H., 1966. Coevolution of mutualism between ants and acacias in Central America. Evolution, 20: 249–275.

Keeler, K.H., 1981. A model of selection for facultative nonsymbiotic mutualism. Am. Nat., 118: 488–498.

Keeler, K.H., 1985. Extrafloral nectaries on plants in communities without ants. Oikos, 44: 407–414.

Knox, R.B., Marginson, R., Kenrick, J. and Beattie, A.J., 1986. The role of extrafloral nectaries inAcacia. B. Juniper and Sir R. Southwood (Editors), Insects and the Plant Surface. Edward Arnold, London, pp. 295–307.

Koptur, S., 1979. Facultative mutualism between weedy vetches bearing extra-floral nectaries and weedy ants in California. Am. J. Bot., 66: 1016–1020.

Koptur, S., 1985. Alternative defenses against herbivores inInga (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) over an elevational gradient. Ecology, 66(5): 1639–1650.

Koptur, S. and Lawton, J.H., 1988. Interactions among vetches bearing extrafloral nectaries, their biotic protective agents, and herbivores. Ecology, 69: 278–283

Lundstroem, A.N., 1887. Pflanzenbiologische Studien II. Die Anpassung der Planzen an Tiere. Nova Acta Reg. Soc. Sc. Uppsala, 13: 1–88.

McMurtry, J.A. and Scriven, G.T., 1964. Studies on the feeding, reproduction, and development ofAmblyseius hibisci (Acarina: Phtoseiidae) on various food substances. Ann. Entom. Soc. Am., 57: 649–655.

McMurtry, J.A. and Scriven, G.T., 1965. Life-history studies ofAmblyseius limonicus with comparative observations onAmblyseius hibisci [Acarina: Phytoseiidae]. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am., 58: 106–111.

McMurtry, J.A. and Scriven, G.T., 1966. Effects of artificial foods on reproduction and development of four species of phytoseiid mites. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am., 59: 267–269.

Muma, M.H., 1971. Food habits of the Phytoseiidae (Acarina: Mesostigmata) including common species on Florida citrus. Fla. Entomol., 54: 21–34.

O'Dowd, D.J. and Wilson, M.F., 1989. Leaf domatia and mites on Australian plants: ecological and evolutionary implications. Biol. J. Linn. Soc., 37: 191–236.

O'Dowd, D.J. and Willson, M.F., 1991. Associations between mites and leaf domatia. Trends Ecol. Evol., 6(6): 179–182.

Pemberton, R.W. and Turner, C.E., 1989. Occurrence of predatory and fungivorous mites in leaf domatia. Am. J. Bot., 76: 105–112.

Pereira, J.F. and Splittstoesser, W.E., 1987. Exudate from cassava leaves. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 18: 191–194.

Pereira, J.F. and Splittstoesser, W.E., 1990. Anatomy of the cassava leaf. Proc. Interam. Soc. Trop. Hort., 34: 73–78.

Pickett, C.H. and Clark, W.D., 1979. The function of extrafloral nectaries inOpuntia acanthocarpa (Cactaceae). Am. J. Bot., 66: 618–625.

Porres, M.A., McMurtry, J.A. and March, R.B., 1975. Investigations of leaf sap feeding by three species of phytoseiid mites by labelling with radioactive phosphoric acid (H3 32PO4). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am., 68: 871–872.

Price, P.W., 1986. Ecological aspects of host plant resistance and biological control: Interactions among three trophic levels. D.J. Boethel and R.D. Eikenbary (Editors), Interactions of Plant Resistance and Parasitoids and Predators of Insects. John Wiley, New York, NY, pp. 11–30.

Pyke, G.H., 1991. What does it cost a plant to produce floral nectar? Nature, 350: 58–59.

Ragusa, S. and Swirski, E., 1977. Feeding habits, post-embryonic and adult survival, mating, virility and fecundity of the predacious miteAmblyseius swirskii [Acarina: Phytoseiidae] on some coccids and mealybugs. Entomophaga, 22: 383–392.

Sadasivam, K.V., 1970. On the composition of leaf exudate and leaf leachate of tapioca (Manihot utilissima Phol.) foliage. Sci. Culture, 36(11): 608–609.

Salick, J., 1983. Natural history of crop-related wild species: uses in pest habitat management. Environ. Manage., 7: 85–90.

Schemske, D.W., 1980. The evolutionarysignificance of extrafloral nectar production byCostus woodsonii (Zingiberaceae): an experimental analysis of ant protection. J. Ecol., 68: 959–967.

Schuster, M.F., Lukefahr, M.J. and Maxwell, F.G., 1976. Impact of nectariless cotton on plant bugs and natural enemies. J. Econ. Entomol., 69: 400–402.

Stephenson, A.G., 1982. The role of the extrafloral nectaries ofCatalpa speciosa in limiting herbivory and increasing fruit production. Ecology, 63: 663–669.

Swirski, E. and Dorzia, N., 1968. Studies on the feeding, development and oviposition of the predaceous miteAmblyseius limonicus Garman and McGregor (Acarina: Phytoseiidae) on various kinds of food substances. Israel J. Agric. Res., 18: 71–75.

Treacy, M.F., Benedict, J.H., Walmsley, M.H., Lopez, J.D. and Morrison, R.K., 1987. Parasitism of bollworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) eggs on nectaried and nectariless cotton. Environ. Entomol., 16: 420–423.

Yokoyama, V.Y., 1978. Relation of seasonal changes in extrafloral nectar and foliar protein and arthropod populations in cotton. Environ. Entomol., 7: 799–802.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bakker, F.M., Klein, M.E. Transtrophic interactions in cassava. Exp Appl Acarol 14, 293–311 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01200569

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01200569