Abstract

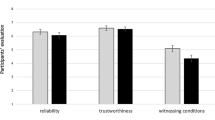

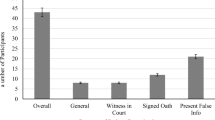

A mock jury study was conducted to test the hypothesis that perceptions of a witness can be biased by presumptuous cross-examination questions. A total of 105 subjects read a rape trial in which the cross-examiner asked a question that implied something negative about the reputation of either the victim or an expert. Within each condition, the question was met with either a denial, an admission, or an objection from the witness's attorney. Results indicated that although ratings of the victim's credibility were not affected by the presumptuous question, the expert's credibility was significantly diminished—even when the question had elicited a denial or a sustained objection. Conceptual and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

A.B.A. Model Rules of Professional Conduct (August, 1983). Washington, DC: American Bar Association.

Bray, R. M., & Kerr, N. L. (1982). Methodological considerations in the study of the psychology of the courtroom. In N. Kerr and R. Bray (Eds.),The psychology of the courtroom (pp. 287–323). New York, Academic Press.

Carretta, T. R., & Moreland, R. L. (1983). The direct and indirect effects of inadmissible evidence.Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 291–309.

Cleary, E. W. (1972),McCormick on evidence (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: West.

Federal Rules of Evidence (1984). St. Paul, MN: West.

Feild, H. S. (1978). Juror background characteristics and attitudes toward rape.Law and Human Behavior 2, 73–93.

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic in conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.),Syntax and semantics (Vol. 3) New York: Academic Press.

Harris, R. J., & Monaco, G. E. (1978). Psychology of pragmatic implication: Information processing between the lines.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 107, 1–22.

Harris, R. J., Teske, R. R., & Ginns, M. J. (1975). Memory for pragmatic implications from courtroom testimony.Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 6, 494–496.

Hopper, R. (1981). The taken, for granted.Human Communication Research, 7, 195–211.

Johnson, M. K. (1987). Discriminating the origin of information. In T. Oltmanns & B. Maher (Eds.).Delusional beliefs: Interdisciplinary perspectives, New York: Wiley.

Johnson, M. K., Bransford, J. D., & Solomon, S. K. (1973) Memory for tacit implications of sentences.Journal of Experimental Psychology, 98, 203–205.

Kalven, H., & Zeisel, H. (1966).The American jury. Boston: Little, Brown.

Kaplan, M. F., & Miller, C. E. (1983). Group discussion and judgment. In P. Paulus (Eds.),Basic group processes (pp. 65–94). New York: Springer Verlag.

Kassin, S. M. (1983). Deposition testimony and the surrogate witness: Evidence for a “messenger effect” in persuasion.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 281–288.

Keeton, R. E. (1973).Trial tactics and methods (2nd ed.). Boston: Little, Brown.

Kelman, H. C., & Hovland, C. T. (1953). “Reinstatement” of the communicator in delayed measurement of opinion change.Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 48, 327–335.

Kestler, J. L. (1982).Questioning techniques and tactics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report.Cognitive Psychology, 7, 560–572.

Loftus, E. F., & Goodman, J. (1985). Questioning witnesses. In S. M. Kassin & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.),The Psychology of evidence and trial procedure (pp. 253–279) Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. P. (1974). Reconstruction of an automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory.Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13, 585–589.

McElhaney, J. W. (1981). Dealing with dirty tricks.Litigation, 7, 45–58.

Morrill, A. E. (1972).Trial diplomacy (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: Court Practice Institute.

Padawer-Singer, A., & Barton, A. H. (1975). Free press, fair trial. In R. J. Simon (Ed.),The jury system: A critical analysis (pp. 123–142). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Pratkanis, A. R., Greenwald, A. G., Leippe, M. R., & Baumgardner, M. (1988). In search of reliable persuasion effects: III. The sleeper effect is dead. Long live the sleeper effect.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 203–218.

Shaffer, D. R. (1985). The defendant's testimony. In S. Kassin & L. Wrightsman (Eds.),The Psychology of evidence and trial procedure (pp. 124–149). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Stasser, G., Kerr, N. L., & Bray, R. M. (1982). The social psychology of jury deliberations: Structure, process, and product. In N. Kerr & R. Bray (Eds.),The psychology of the courtroom (pp. 221–256). NY: Academic Press.

Sue, S., Smith, R. E., & Caldwell, C. (1973). Effects of inadmissible evidence on the decisions of simulated jurors: A moral dilemma.Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3, 345–353.

Swann, W. B., Guiliano, T., & Wegner, D. M. (1982). Where leading questions can lead: The power of conjecture in social interaction.Journal of Personaliry and Social Psychology, 42, 1025–1035.

Thompson, W. C., Fong, G. T., & Rosenhan, D. L. (1981). Inadmissible evidence and juror verdicts.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 453–463.

Underwood, R. H. (1982). Adversary ethics: More dirty tricks.American Journal of Trial Advocacy, 6, 265–309.

Underwood, R. H., & Fortune, W. H. (1988).Trial ethics. Boston: Little Brown.

U.S. v. Brown. 519 F.2d 1368 (6th Cir. 1975).

U.S. v. Cardarella, 570 F.2d 264 (8th Cir. 1978).

U.S. v. Pugliese, 153 F.2d 497 (2nd Cir. 1945).

Wegner, D. A., Wenclaff, R., Kerker, R. M., & Beattie, A. E. (1981). Incrimination through innuendo: Can media questions become public answers?Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 822–832.

Wellman, F. L. (1936).The art of cross examination (2nd ed.). New York: Coller.

Wolf, S., & Montgomery, D. A. (1977). Effects of inadmissible evidence and level of judicial admonishment to disregard on the judgments of mock jurors.Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 7, 205–219.

Yandell, B. (1979). Those who protest too much are seen as guilty.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 5, 44–47.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This research was supported by funds provided to the first author by the Bronfman Science Center.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassin, S.M., Williams, L.N. & Saunders, C.L. Dirty tricks of cross-examination. Law Hum Behav 14, 373–384 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01068162

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01068162