... though people can adjust satisfactorily to random uncertainty, which can be dealt with through insurance, including self-insurance, they remain on edge when contemplating the possibility of strategically determined losses. For when the bearing of strategy is evident, one faces the risk of beingsystematically imposed upon, which seems a risk of a very different order from the risk of occasional, accidental injury. One faces also the rational necessity of devoting a large proportion of his energies and resources to counter-strategy aimed at fending off the risk; where the possibility of loss will be visibly determined by strategy, that possibility cannot be conveniently dismissed from consciousness on the ground that, being uncontrollable, it is not worth thinking about.

Frank Michelman (1967: page 1217)

With some fixed probability, an exogenous event will occur that will make a parcel of land sufficiently valuable for public use so as to trigger a government decision to take the land.

Blume, Rubinfeld and Shapiro (1984: page 72)

Abstract

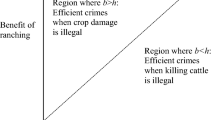

When should government compensate citizens for harm inflicted by public policy? In practice, all public policy is harmful to somebody, even when it is beneficial to society as a whole. The common view in the legal profession is that a fuzzy but serviceable line can be drawn between “taking” which should be compensated and the proper exercise of the “policy power” where no compensation is warranted. Recently this view has been challenged by some authors who argue that harm to victims of socially-advantageous public policy should never be compensated, and by others who argue that compensation is almost always warranted. The latter would go so far as to proscribe all redistribution of income as a “taking” from the well-to-do. This paper is a defense of the common view against both challenges. The key to the problem is the distinction between unalterable risk and the risk of victimization of citizens by the government, giving rise to rent-seeking and a general disorganization of society.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Atkinson, A.B. (1973). How progressive should the income tax be? In E. Phelps (Ed.),Economic justice. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Blume, L. and Rubinfeld, D.I. (1984). Compensation for takings: An economic analysis.California Law Review 72: 569–624.

Blume, L., Rubinfeld, D.L. and Shapiro, P. (1984). The taking of land: When should compensation be paid?Quarterly Journal of Economics 99: 71–92.

Epstein, R.A. (1985).Takings: Private property and the power of eminent domain. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Farber, D. (1992). Economic analysis and just compensation.International Review of Law and Economics 12: 125–138.

Fischel, W. A. and Shapiro, P. (1989). A constitutional choice model of compensation for takings.International Review of Law and Economics 9: 115–128.

Kaplow, L. (1986). An economic analysis of legal transactions.Harvard Law Review 99: 509–617.

Krueger, A.O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society.American Economic Review 64: 291–303.

Mercuro, N. (Ed.) (1992).Taking property and just compensation. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Michelman, F.I. (1967). Property, utility and fairness: Comments on the ethical foundations of “just compensation” law.Harvard Law Review 80: 1165–1258.

Munch, P. (1976). An economic analysis of eminent domain.Journal of Political Economy 84: 473–497.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1989). Dikes, dams and vicious hogs: Entitlement and efficiency in tort law.Journal of Legal Studies 18: 25–50.

Sax, J.L. (1964). Takings and the police power.The Yale Law Journal 75: 36–76.

Simons, H.C. (1938).Personal income taxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sterk, S.E. (1988). Nollan, Henry George, and exactions.Columbia Law Review 88: 1731–1751.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent-seeking. In Buchanan, J.M., Tollison, R. and Tullock, G. (Eds.),Towards a theory of the rent-seeking society. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

Ulen, T.S. (1992). The public use of private property: A dual-constraint theory of efficient government takings. In N. Mercuro (Ed.), Taking property and just compensation. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Usher, D. (1980).The economic prerequisite to democracy. Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

Usher, D. (1991). The hidden cost of public expenditure. In R. Bird (Ed.),More taxing than taxes? San Francisco: ICS Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This paper was written while on sabbatical at the economics department of the University of British Columbia. I thank the faculty and staff at the economics department for making me welcome.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Usher, D. Victimization, rent-seeking and just compensation. Public Choice 83, 1–20 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01047680

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01047680