Abstract

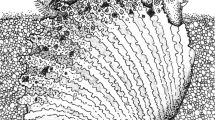

The life-history of the blue-ringed octopus Hapalochlaena maculosa (Hoyle) was observed in laboratory aquaria. Eggs from a brooding female were bred through to the next generation. The life cycle lasts approximately 7 months–4 months from hatching to maturity, 1 month from copulation to egg-laying, and an estimated 2 months for embryonic development. This venomous octopus has several unique and interesting habits. Eggs are not attached to a substratum but are carried by the mother throughout their embryonic life. She assumes a brooding posture for the greater part of the time and cradles the eggs between her raised skirt and body. However, she can move froely with her clutch of eggs, conveying them individually or in clusters along her arms from one sucker to the next as occasion demands. Embryos reverse position within their capsules 1 week prior to hatching, and hatch at the distal end of the capsule, mantle-first. Development is direct; there is no planktonic stage. The young immediately assume a benthic habit and, within a few hours, consume the remnant of the yolk-sac which they carry with them from the egg. Juveniles begin to feed on pieces of crab within a week of hatching, and to kill and eat live crabs within a month. They pierce the carapace of their prey at the abdominal articulation and with the aid, apparently, of venom from their posterior salivary glands suck out the partially pre-digested tissues. The ink gland is relatively small in size and is mainly used between the second and the fourth week of juvenile life. Chromatophores begin to function during embryonic life. After hatching there is a progressive change in coloration, and the iridescent blue rings which characterize the species appear at the age of about 6 weeks. Mating is a more active process than has been recorded for other octopuses. The male mounts the female and clasps her securely. After a short struggle the female becomes quite passive, almost inert. Copulation lasts about one hour. The unusual life-history of H. maculosa suggests that it is a highly evolved octopus species. Its direct development, simple diet, and rapid rate of growth make the animal relatively easy to cultivate for experimental or pharmacological purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Batham, E. J.: Care of eggs by Octopus maorum. Trans. R. Soc. N.Z. 84 (3), 629–638 (1957).

Brough, E. J.: Egg-care, eggs, and larvae in the midget octopus Robsonella australis (Hoyle). Trans. R. Soc. N.Z. 6 (2), 7–19 (1965)

Dew, B.: Some observations on the development of two Australian octopuses. The mar. Zool. 1 (7), 44–52 (1959).

Fisher, W. K.: Brooding habits of a cephalopod. Ann. Mag. nat. Hist. 12, 147–149 (1923).

Freeman, S. E. and R. J. Turner: Maculotoxin, a potent toxin secreted by Octopus maculosus Hoyle. Toxic. appl. Pharmac. 16, 681–690 (1970).

Joubin, L.: Cephalopodes des croisiéres du Dana. Annls Inst. océanogr., Monaco 7, 1–24 (1929).

Lane, F. W.: Kingdom of the octopus, 287 pp. London: Jarrolds 1957.

Le Souef, A. S. and J. Allen: Breeding habits of a female octopus. Aust. Zool. 9, 64–67 (1933).

McMichael, D. F.: Mollusks — classification, distribution, venom apparatus and venoms. Symptomatology of stings. In. Venomous animals and their venoms. III Venomous invertebrates, pp 373–393. Ed. by W. Bucherl and E. E. Buckley. New York: Academic Press 1971.

Messenger, J. B.: Behaviour of young Octopus briareus Robson. Nature, Lond. 197, 1186–1187 (1963).

Naef, A.: Die Cephalopoden. Fauna, Flora Golfo Napoli. 35, 1–863 (1921/1923).

Robson, G. C.: A monograph of the recent Cephalopoda based on the collections in the British Museum (Natural History). Part 1. Octopodinae, 236 pp. London: British Museum 1929.

Sutherland, S. K. and W. R. Lane: Toxins and mode of envenomation of the common ringed or blue-banded octopus. Med. J. Aust. 1, 893–898 (1969).

Vevers, H. G.: Observations on the laying and hatching of octopus eggs in the Society's aquarium. Proc. zool. Soc. Lond. 137, 311–315 (1961).

Wells, M. J.: Brain and behaviour in cephalopods, 171 pp. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1962.

— and J. Wells: Observations on the feeding, growth rate and habits of newly settled Octopus cyanea. J. Zool. London 161, 65–74 (1970).

Wells, M. M.: Breeding habits of octopus. Science, N. Y. 68, p. 482 (1928).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Communicated by G. F. Humphrey, Sydney

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tranter, D.J., Augustine, O. Observations on the life history of the blue-ringed octopus Hapalochlaena maculosa . Marine Biology 18, 115–128 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00348686

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00348686