Summary

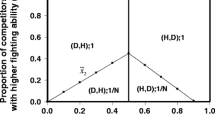

Winners of aggressive interactions often continue to win in future encounters. I propose that this phenomenon is a by-product of two other phenomena occurring simultaneously: first, initiators of aggressive interactions typically win those interactions and, second, winners of aggressive encounters often become more likely to initiate future interactions. I propose that these phenomena can be explained, in turn, by selection favoring an individual's initiating an interaction only when it is likely to win that interaction. I found support for this two-step explanation for the winning begets winning phenomenon by observing aggressive interactions among captive dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis oreganus). First, initiators of interactions almost always won. Second, based on characteristics of winners in birds' home aviaries, I could predict which birds would initiate against novel competitors — winners were long-winged males with dark hoods, and birds with these characteristics were more likely to be the first to initiate in novel triads. In addition, aggression was directed preferentially towards other dark-hooded males. The results of this study may expand our understanding of the dynamics of aggressive interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Balph MH (1977) Winter social behaviour of dark-eyed juncos: communication, social organization, and ecological implications. Anim Behav 25:859–884

Bekoff M, Scott AC (1989) Aggression, dominance and social organization in evening grosbeaks. Ethology 83:177–194

Benton D, Brain PF (1979) Behavioural comparisons of isolated, dominant and subordinate mice. Behav Proc 4:211–219

Chase ID (1980) Social process and hierarchy formation in animal societies. Am Soc Rev 45:905–924

Collias NC (1943) Statistical analysis of factors which make for success in initial encounters between hens. Am Nat 77:519–538

Francis RC (1983) Experiential effects on agonistic behaviour in the paradise fish, Macropodus opercularis. Behaviour 85:292–913

Freeman S, Jackson WM (1990) Univariate metrics are not adequate for measuring avian body size. Auk 107:69–74

Ginsburg B, Allee WC (1942) Some effects of conditioning on social dominance and subordination in inbred strains of mice. Physiol Zool 15:485–506

Holberton RL, Able KP, Wingfield JC (1989) Status signalling in dark-eyed juncos, Junco hyemalis: plumage manipulations and hormonal correlates of dominance. Anim Behav 37:681–689

Holford TR, White C, Kelsey JL (1978) Multivariate analysis for matched case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 107:245–256

Jackson WM (1988) Can individual differences in history of dominance explain the development of linear dominance hierarchies? Ethology 79:71–77

Kahn MW (1951) The effect of severe defeat at various age levels on the aggressive behavior of mice. J Genet Psychol 79:117–130

Ketterson ED (1979) Aggressive behavior in wintering dark-eyed juncos: determinants of dominance and their possible relation to geographic variation in sex ratio. Wilson Bull 91:371–383

McHugh T (1958) Social behavior of the American buffalo (Bison bison bison). Zoologica 43:1–40

Meese GB, Ewbank R (1973) The establishment and nature of the dominance hierarchy in the domesticated pig. Anim Behav 21:326–334

Munsell Color, Inc (1976) Munsell book of color. Kollmorgen, Baltimore

Poll NE van de, Dejonge F, Oyen HG van, Pett J van (1982) Aggressive behaviour in rats: Effects of winning and losing on subsequent aggressive interactions. Behav Proc 7:143–155

Popp JW (1988) Effects of experience on agonistic behavior among goldfinches. Behav Proc 16:11–19

Ratner SC (1961) Effect of learning to be submissive on status in the peck order of domestic fowl. Anim Behav 9:34–37

Reinhardt V, Reinhardt A (1975) Dynamics of social hierarchy in a dairy herd. Z Tierpsychol 38:315–323

Rohwer S (1985) Dyed birds achieve higher social status than controls in Harris' sparrows. Anim Behav 33:1325–1331

Rohwer S, Ewald PW (1981) The cost of dominance and advantage of subordination in a badge signaling system. Evolution 35:441–454

Rowell T (1966) Hierarchy in the organization of a captive baboon group. Anim Behav 14:430–443

Thouless CR, Guinness FE (1986) Conflict between red deer hinds: the winner always wins. Anim Behav 34:1166–1171

Tyler SJ (1972) The behaviour and social organisation of New Forest ponies. Anim Behav Monogr 5:87–196

Walker Leonard J (1979) A strategy approach to the study of primate dominance behavior. Behav Proc 4:155–172

Wilkinson L (1989) SYSTAT: the system for statistics. SYSTAT, Evanston IL

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, W.M. Why do winners keep winning?. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 28, 271–276 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00175100

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00175100