Abstract

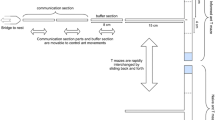

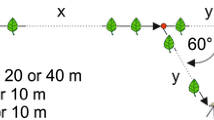

The study of location specification in recruitment communication by bees has focused on two dimensions: direction and distance from the nest. Yet the third dimension, height above ground, may be significant in the tall and dense forest habitats of stingless bees. Foragers of the stingless bee Scaptotrigona postica recruit to a specific three-dimensional location by laying a scent trail. Stingless bees in the genus Melipona are thought to have a more sophisticated recruitment system that communicates distance through sounds inside the nest and direction through pointing zig-zag flights outside the nest. However, prior research on Melipona has not examined height communication or even established that foragers can recruit newcomers to a specific location. We used identical paired feeders to investigate recruitment to food in M panamica on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. We trained foragers from an observation hive to one feeder and monitored both feeders for the subsequent arrival of newcomers. We changed the relative positions of the feeders to test for correct direction, distance, and canopy-level communication. A 40-m canopy tower located inside the forest enabled us to examine canopy-level communication. We found that M. panamica foragers can recruit to a specific (1) direction, (2) distance, and (3) canopy level. To test the possibility that foragers accomplish this by means of a scent trail, we placed the colony on one shore of a small cove and trained bees over 116 m of open water to a feeder located on the opposite shore. We also placed a second feeder on this shore, equidistant from the colony but 20 m from the first feeder. Significantly more newcomers consistently arrived at the feeder visited by the foragers. Thus foragers evidently do not need a scent trail to communicate direction. Inside the nest, a forager produces pulsed sounds while visibly vibrating her wings after returning from a good food source. She is attended by other bees who cluster and hold their antennae around her, following her as she rapidly spins clockwise and counterclockwise. Locational information may be encoded in this behavior. However, foragers may also directly lead newcomers to the food source. Further experiments are planned to test for such piloting and other communication mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Esch H (1967) Die Bedeutung der Lauterzeugung für die Verständigung der stachellosen Bienen. Z Vergl Physiol 56: 408–411.

Esch H, Esch I, Kerr WE (1965) Sound: an element common to communication of stingless bees and to dances of the honey bee. Science 149: 320–321.

Frisch K von (1967) The dance language and orientation of bees (translated by Leigh E. Chadwick) Belknap, Cambridge.

Gould JL, Henerey M, MacLeod MC (1970) Communication of direction by the honey bee. Science 169: 544–554.

Hertel H, Ventura DF (1985) Spectral sensitivity of photoreceptors in the compound eye of stingless tropical bees. J Insect Physiol 31(12): 931–935.

Hölldobler B, Wilson EO (1990) The ants. Belknap, Cambridge.

Kerr WE (1960) Evolution of communication in bees and its role in speciation. Evolution 14: 386.

Kerr WE (1969) Some aspects of the evolution of social bees. Evol Biol 3: 119–175.

Kerr WE (1994) Communication among Melipona workers (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J Insect Behav 7: 123–128.

Kerr WE, Rocha R (1988) Comunicação em Melipona rufiventris e Melipona compressipes. Ciência Cultura 40: 1200–1203.

Kerr WE, Ferreira A, Mattos NS de (1963) Communication among stingless bees — additional data. J N Y Entomol Soc 71: 80–90.

Kerr WE, Blum M, Fales HM (1981) Communication of food source between workers of Trigona (Trigona) spinipes. Rev Brasil Biol 41: 619–623.

Lindauer M, Kerr WE (1960) Communication between the workers of stingless bees. Bee World 41: 29–41, 65–71.

Michener CD (1990) Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera). Univ Kansas Sci Bull 54: 75–164.

Roubik DW (1989) Ecology and natural history of tropical bees. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Roubik DW (1992) Stingless bees: a guide to Panamanian and Mesoamerican species and their hives (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponinae). In: Quintero D, Aiello A (eds) Insects of Panama and Mesoamerica: selected studies. Oxford Science, Oxford, pp 495–524.

Roubik DW, Aluja M (1983) Flight ranges of Melipona and Trigona in tropical forest. J Kans Entomol Soc 56: 217–222.

Roubik DW, Buchmann SL (1984) Nectar selection by Melipona and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and the ecology of nectar intake by bee colonies in a tropical forest. Oecologia 61: 1–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Communicated by R.F.A. Moritz

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nieh, J.C., Roubik, D.W. A stingless bee (Melipona panamica) indicates food location without using a scent trail. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 37, 63–70 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00173900

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00173900