Concluding remarks

While the final version of the 1986 Tax Reform Act retained budget funding of the IRS, the Senate proposal to finance spending from audit revenues represented a seriously debated alternative that continues to receive attention as a method for increasing enforcement. At one level, the ultimate failure of the proposal is puzzling. Given Congress's unwillingness to raise tax rates to cover spending, the budget deficits of the 1980s must be financed from some other source — inflation, borrowing or increased enforcement. Turning the IRS into a bounty-hunting agency would seem to be a straightforward way of producing extra revenue.

This popular view reveals a basic confusion about the behavior of bounty-hunting agents. It implicitly assumes that a bounty-hunting agency would behave as a general revenue-maximizing Leviathan and automatically increase enforcement above the status quo budgetary level in pursuit of additional revenue. But bounty hunters want to maximize net audit revenues — not net general revenues. As I have emphasized, too thorough a hunt will reduce the bounty.

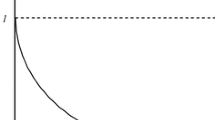

The possibility of taxpayer adjustment implies a Laffer-like relationship between audit revenue and enforcement. Conceivably, enforcement activity could be raised to the point where taxpayers choose to report all of their income. Then audits would raise no revenue. Increased revenue and increased output in the form of enforcement do not necessarily go hand-in-hand. Allowing pure bounty hunters to spend all audit revenues could lead to either increased or decreased enforcement.

Conceptually, Congress could obtain the enforcement outcome it desired by determining the representative individual's taxable base (Y), calculating the taxpayer response to changes in enforcement (dx*/dL), choosing the ‘correct’ model of the agency head's behavior and finally specifying in the financial proposal the appropriate fraction, m, of audit revenues that agents may spend.

One potential problem with this procedure is its presumption that information is costlessly available to Congress. If Congress does not know how taxpayers respond to changes in enforcement, for instance, then it might miscalculate the appropriate revenue fraction. Indeed, my tentative prediction that the Senate's revenue multiple would have lowered enforcement suggests the difficulties in specifying the ‘correct’ multiple.

But this problem would not appear to be insurmountable. In a static environment, where the taxpayer adjustment function does not change over time, Congress could discover the ‘correct’ revenue multiple through a trial and error process. Then, at a later date, Congress could amend the financing structure accordingly.

A more serious problem confronts Congress once we acknowledge that the economic environment may change. Consider the possibility that taxpayer income changes within and across legislative periods. A revenue fraction that was appropriate initially would not necessarily be appropriate several years, or even months later. This helps explain why the Senate proposal ultimately failed even though it seemed ideally suited for the revenue ‘crisis’ of the 1980s.

The failure of the 1986 proposal also suggests why legislators choose to budget finance the operation of most bureaus rather than place them on a type of performance payment schedule. Once government specifies a payment formula, it loses control of the bureau's output over the contract period. In contrast, the appropriation process allows government to use the budget as a tool to induce in-period and across-period adjustments in the output of a bureau when conditions outside legislators' control change unexpectedly.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allingham, M.G., and Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1: 323–338.

Joint Committee on Taxation. (1986), July 15. Comparison of tax reform provisions of H.R. 3838 as passed by the House and the Senate. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office.

Keating, D. (1986, July 8). Don't tempt the IRS into bounty hunting. The Wall Street Journal: 30.

Meyers, H.G. (1986). Optimal level of enforcement for the Internal Revenue Service. Unpublished manuscript. Office of Management and Budget, Special Studies Division/Economics and Government.

Moene, K.O. (1986). Types of bureaucratic interaction. Journal of Public Economics 29: 333–345.

Pauly, M., and Redisch, M. (1973). The not-for-profit hospital as a physician's cooperative. American Economic Review 63: 87–100.

Slemrod, J., and Yitzhaki, S. (1985). On the optimum size of a tax administration agency. Cambridge, MA: NBER working paper 1759.

Steuerle, E.C. (1986). Who should pay for collecting taxes? Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Weingast, B.R., and Moran, M. (1983). Bureaucratic discretion or congressional control: Regulatory policymaking by the FTC. Journal of Political Economy: 765–800.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Comments received at a Miami University Micro Workshop significantly improved the paper. Also, long discussions with Bill Even, Bill Hoyt and Genia Toma helped clarify my thoughts on the subject. I am responsible for any remaining errors or omissions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toma, M. Will bounty-hunting revenue agents increase enforcement?. Public Choice 61, 247–260 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00123887

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00123887