Abstract

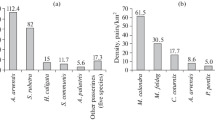

By comparison with deciduous oaks, the lower yearly production of new leaves in sclerophyllous oaks is hypothesized to have several consequences on animal communities. In particular, the production of arthropod communities that feed upon the leaves should be lower in sclerophyllous than in deciduous oaks, this causing changes in breeding patterns and the demographic balance in insectivorous birds. Studies in both deciduous and sclerophyllous habitats in southern France have shown that: 1) the spring development of new leaves occurs later and more slowly in sclerophyllous than in deciduous oaks, 2) the biomass of caterpillars is much lower in sclerophyllous oak forests, and 3) there is a large variation in life history traits of the Blue Tit depending in which type of habitat they breed. Laying date occurs later and clutch size is lower in sclerophyllous habitats than in deciduous habitats. The evolution of life history traits is discussed according to whether poor sclerophyllous habitats are isolated (e.g. on Corsica) or are parts of landscapes including both habitat types.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Balen, J. H., van. 1973. A comparative study of the breeding ecology of the Great Tit Parus major in different habitats. Ardea 61: 1–93.

Blondel, J., 1985. Breeding strategies of the Blue Tit and the Coal Tit (Parus) in mainland and island Mediterranean habitats: a comparison. J. Anim. Ecol. 54: 531–556.

Blondel, J., Clamens, A., Cramm, P., Gaubert, H. & Isenmann, P. 1987. Population studies of tits in the Mediterranean region. Ardea 75: 21–34.

Blondel, J., Dervieux, A., Maistre, M. & Perret, Ph. 1991. Feeding ecology and life history variation of the Blue Tit in Mediterranean deciduous and sclerophyllous habitats. Oecologia 88: 9–14.

Blondel, J., Perret, Ph. & Maistre, M. 1990. On the genetical basis of the laying date in an island population of Blue Tit. J. Evol. Biol. 3: 469–475.

Blondel, J. & Pradel, R. 1990. Is adult survival of the Blue Tit higher in a low fecundity insular population than in a high fecundity one? Pages 131–143. In: J., Blondel, A., Gosler, J. D., Lebreton and R., McCleery (eds.). Population biology of passerine birds. An integrated approach. NATO ASI Series G, vol. 24. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Clamens, A. 1990. Influence of Oak (Quercus) leafing on Blue Tits (Parus caeruleus) laying date in Mediterranean habitats. Acta Oecologica 11: 539–544.

Cody, M. L. 1981. Habitat selection in birds: the roles of vegetation structure, competitors, and productivity. BioScience 31: 107–113.

Cramm, P. 1982. La reproduction des Mésanges dans une chênaie verte du Languedoc. L'Oiseau 52: 347–360.

Dajoz, R. 1980. Ecologie des insectes forestiers. Gauthier-Villars, Paris.

Drent, R. H. & Daan, S. 1980. The prudent parent: energetic adjustments in avian breeding. Ardea 68: 225–252.

Du, Merle, P., & Mazet, R. 1983. Stades phénologiques et infestation par Tortrix viridana L. (Lep., Tortricidae) des bourgeons du chêne pubescent et du chêne vert. Acta Oecologica/Oecol. Applic 4: 47–53.

Edney, E. B. 1977. Water balance in land arthropods. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

Favard, P. 1962. Contribution à l'étude de la faune entomologique du Chêne vert en Provence. Thèse, Univ. Aix-Marseille.

Feeny, P. P. 1975. Biochemical coevolution between plants and their insect herbivores. Pages 3–19. In: L. E., Gilbert and P. H., Raven (Eds.). Coevolution of Plants and Animals. Texas, Univ. Texas Press.

Floret, Ch., Galan, M. J., Le, Floch, E., Leprince, F. & Romane, F. 1989. Pages 9–97. In g., Orshan (Ed.), Plant pheno-morphological Studies in Mediterranean Type Ecosystems. Kluwer Academic Publ., Dordrecht.

Harper, J. L. 1977. Population biology of plants. Academic Press, London.

Isenmann, P., Cramm, P. &Clamens, A. 1987. Etude comparée de l'adaptation des mésanges du genre Parus aux différentes essences forestières du bassin méditerranéen occidental. Rev. Ecol. (Terre et Vie) Suppl 4: 17–25.

Lack, D. 1950. The breeding seasons of European birds. Ibis 92: 288–316.

Lack, D. 1954. The Natural Regulation of Animal Numbers. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Lebreton, Ph. 1982. Tanins ou alcaloïdes: deux tactiques phytochimiques de dissuasion des herbivores. Rev. Ecol. (Terre et Vie). 36: 539–572.

Liebhold, A. M. & Elkinton, J. S. 1988. Techniques for estimating the density of late-instar Gypsy Moth, Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae), populations using frass drop and frass production measurements. Environ. Entomol. 17: 381–384.

Martin, T. E. 1987. Food as a limit on breeding birds: a life-history perspective. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18: 453–487.

Monk, C. D. 1966. An ecological significance of evergreenness. Ecology 47: 504–505.

Newton, I. 1980. The role of food in limiting bird numbers. Ardea 68: 11–30.

Noordwijk, A., van. 1987. Quantitative Ecological Genetics of Great Tits. Pages 363–380. In F., Cooke and P. A., Buckley (eds.). Avian Genetics. Academic Press, London.

Owen, D. F. 1977. Latitudinal gradients of clutch size: an extension of David Lack's theory. Pages 170–180. In B., Stonehouse and C. M., Perrins (eds.). Evolutionary Ecology. Macmillan, London.

Perrins, C. M. 1965. Population fluctuations and clutch-size in the Great tit (Parus major). J. Anim. Ecol. 34: 601–647.

Perrins, C. M. 1970. The timing of birds' breeding seasons. Ibis 112: 242–255.

Perrins, C. M. 1979. British Tits. Collins, London.

Pulliam, H. R. 1988. Sources, sinks, and population regulation. Am. Nat. 132: 652–661.

Royama, T. 1970. Factors governing the hunting behaviour and selection of food by the Great tit (Parus major L.). J. Anim. Ecol. 39: 619–668.

Tinbergen, L. 1960. The natural control of insects in pinewoods. I. Factors influencing the intensity of predation by songbirds. Archives Néerlandaises de Zoologie 13: 265–336.

Varley, G. C. 1967. The effects of grazing by animals on plant productivity. Pages 773–777. In K. Petrusewicz (ed.). Secondary productivity of terrestrial ecosystems.

Wiens, J. A. & Rotenberry, J. T. 1981. Censusing and the evaluation of avian habitat occupancy. Stud. Avian Biol. 6: 522–532.

Zandt, H., Strijkstra, A., Blondel, J. & van, Balen, H. 1990. Food in two Mediterranean Blue Tit populations: Do differences in caterpillar availability explain differences in timing of the breeding season? Pages 145–155. In J., Blondel, A., Gosler, J. D., Lebreton and R., McCleery (eds.). Population biology of passerine birds, An integrated approach. NATO ASI Series G, vol 24. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blondel, J., Isenmann, P., Maistre, M. et al. What are the consequences of being a downy oak (quercus pubescens) or a holm oak (Q. ilex) for breeding blue tits (Parus caeruleus)?. Vegetatio 99, 129–136 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00118218

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00118218