Abstract

Introduction

This study sought to compare efficacy and safety of ferric carboxymaltose vs. placebo in iron-deficient patients with fibromyalgia.

Methods

This blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study randomized adults with fibromyalgia and Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR) scores ≥ 60, ferritin levels < 0.05 µg/ml, and transferrin saturation < 20% (1:1) to receive ferric carboxymaltose [15 mg/kg (up to 750 mg)], or placebo (15 cc normal saline) intravenously on study days 0 and 5. Patients visited the clinic on days 14, 28, and 42 for efficacy and safety assessments. The primary efficacy endpoint was proportion of patients with a ≥ 13-point improvement from baseline to day 42 in FIQR scale score. Secondary endpoints included changes from baseline in FIQR scale, Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) total score, Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep scale, Fatigue Visual Numeric Scale (VNS), iron indices (transferrin saturation and ferritin), and safety.

Results

The efficacy analysis group comprised 80 patients, and the safety analysis group comprised 81. More ferric carboxymaltose patients (77%) vs. placebo patients (67%) achieved the primary endpoint, but the difference was not significant. Greater improvements from baseline to day 42 were observed for ferric carboxymaltose vs. placebo in FIQR total score, BPI total score, Fatigue VNS score, and iron indices. Mean changes in MOS Sleep scale scores were similar between groups. Ferric carboxymaltose was safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

Compared with placebo, ferric carboxymaltose improved measures of fibromyalgia severity and was well tolerated. The current results suggest that ferric carboxymaltose shows benefit in iron-deficient patients with concurrent fibromyalgia.

Funding

Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02409459.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a disorder characterized by chronic widespread pain in conjunction with multiple other symptoms, including tenderness, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, insomnia, depression, anxiety, and stiffness, that cause functional impairment [1]. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the United States is estimated to range from 2 to 8%, depending on which diagnostic criteria are applied [2]. Although fibromyalgia affects both sexes, it is more prevalent among women [3, 4]. Key diagnostic criteria include widespread pain index and symptom severity scores within specific boundaries, presence of unremitting symptoms for ≥ 3 months, and absence of another diagnosis that would otherwise account for the pain [5].

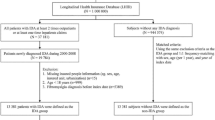

Fibromyalgia syndrome is associated with dysfunctional pain processing in the central nervous system. Studies have shown that patients with fibromyalgia have reduced levels of biogenic amine metabolites, including dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, in their cerebrospinal fluid [6, 7]. It has been suggested that decreased iron stores lead to a reduced production of biogenic amines since iron is essential for neurotransmitter synthesis [8]. As a result, several studies have evaluated the association between iron deficiency and fibromyalgia. Kim and colleagues [9] noted that the concentrations of calcium, magnesium, and iron in the hair of women with fibromyalgia were lower than in the hair of control patients, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Pamuk and colleagues [10] demonstrated that the prevalence of fibromyalgia among patients with iron-deficiency anemia and thalassemia minor was higher than among control patients. Finally, Ortancil and colleagues [8] reported that mean serum ferritin levels were lower in patients with fibromyalgia than in control patients. Together, these studies indicate a potential link of iron deficiency to fibromyalgia.

Iron replacement therapy can be administered orally or parenterally [11,12,13]. Oral iron supplementation is usually the first line of therapy for iron-deficiency anemia when fast repletion is not required [11, 14]. Intravenous (IV) iron provides a more rapid repletion of iron stores than oral iron and is indicated in patients who are unresponsive to, intolerant of, or noncompliant with oral iron regimens [12, 13].

Ferric carboxymaltose is a polynuclear iron (III)-hydroxide carbohydrate complex designed to mimic physiologic ferritin by producing a slow, controlled delivery of complexed iron to endogenous ferritin and transferrin iron–binding sites [15, 16]. Ferric carboxymaltose was approved in 2013 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in adults who are intolerant of oral iron or have an unsatisfactory response to oral iron or who have non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease [17]. In several clinical trials, ferric carboxymaltose has demonstrated superiority compared with placebo and noninferior or superior efficacy compared with oral iron or other IV iron products [18]. The present study evaluated the efficacy and safety of ferric carboxymaltose compared with placebo in iron-deficient patients with fibromyalgia.

Methods

Study Design

This blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study was conducted in the United States March to October 2015. The study consisted of up to a 14-day screening phase to assess patient eligibility, a 5-day treatment phase during which patients received treatment on days 0 and 5, and an assessment phase during which patients visited the clinic on days 14, 28, and 42 for efficacy and safety assessments. During the screening phase, patients provided a complete medical history (including prior iron therapy use); underwent a physical examination including vital signs, pregnancy test (for women of child bearing potential), and hematology parameters such as iron indices, chemistry, and hepcidin levels; and completed the International Restless Legs Syndrome (IRLS) scale. The IRLS is a 10-item questionnaire that measures two dimensions of restless legs syndrome (symptoms and symptoms impact); each item is rated on a four-point scale (0 = none to 4 = very severe), and total score is a sum of the individual item scores (mild = 1–10 points; moderate = 11–20 points; severe = 21–30 points; and very severe = 31–40 points). Because one-third of patients with fibromyalgia also have restless legs syndrome and studies have demonstrated symptomatic improvement with ferric carboxymaltose [19], study patients were screened for this disorder [20, 21] and the IRLS was used as a potential explanatory factor for observed changes from baseline in Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR) [22] scores.

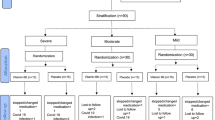

Eligible patients who met inclusion criteria were randomized 1:1 based on a predetermined randomization schedule via an electronic data capture system to receive two 15 mg/kg (up to 750 mg) undiluted blinded doses of IV ferric carboxymaltose at 100 mg/min (1 dose on day 0 and 1 on day 5) or blinded placebo doses (15 cc normal saline) IV push at 2 ml/min on the same schedule. The patients, investigator, and study staff were blinded to the assignments; personnel who randomized patients, who prepared, concealed, and administered study drug (since ferric carboxymaltose is reddish-brown and slightly viscous), and who completed drug-specific clinical trial documentation had access to study assignments.

This study was conducted in accordance with the United States Code of Federal Regulations on Protection of Human Subjects (21 CFR 50), institutional review board regulations, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, 21 CFR Part 312, and applicable International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines, as well as local and state regulations. All study participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT02409459).

Concomitant medications and their route and duration of administration were recorded. No additional iron supplementation was allowed, including IV iron from 30 days before consent and oral iron (e.g., multivitamins with iron) from time of consent.

Patients

Men and women aged ≥ 18 years were eligible to participate if they had a diagnosis of fibromyalgia based on the 2011 modification of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2010 preliminary criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia [23]. Other key inclusion criteria included a baseline score ≥ 60 on the FIQR and stable dose(s) of fibromyalgia medications and narcotics ≥ 30 days before randomization. Key exclusion criteria included parenteral iron use within 4 weeks before screening, an anticipated need for blood transfusion during the study, baseline ferritin level ≥ 0.05 µg/ml, baseline transferrin saturation ≥ 20%, hemoglobin above the upper limit of normal, known hypersensitivity reaction to any component of ferric carboxymaltose, and calcium or phosphorous concentrations outside the normal range. Additional exclusion criteria included current infection other than viral upper respiratory tract infection, malignancy (unless skin cancer or cancer free for ≥ 5 years), active inflammatory arthritis, pregnancy or lactation, severe peripheral vascular disease with significant skin changes, medication use for seizure disorders, history of iron storage disorders, hepatitis with evidence of active disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and chronic alcohol or drug abuse within the preceding 6 months.

Any patient who had an intervention for fibromyalgia was no longer eligible for efficacy evaluation starting at the time of the intervention but remained in the study for safety evaluation. An intervention was defined as the initiation of a new treatment or increase of a previously prescribed fibromyalgia treatment following the patient’s assessment that current symptoms were intolerable.

Study Assessments and Endpoints

On day 0, before study drug administration, and on days 14, 28, and 42 (or at the end of study/early termination), patients completed the following: FIQR Scale, Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) short-form (measuring Pain Severity and Pain Interference), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, and Fatigue Visual Numeric Scale (VNS). Hematology, including iron indices, chemistry, and hepcidin levels, were evaluated during screening (days − 14 to − 4) and on day 42 (or end of study/early termination). Adverse events (AEs) were collected on days 0, 5, 14, 28, and 42 (or at end of study/early termination). All AEs were graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event, Version 4, or a protocol-specified alternative if a criterion did not exist.

The primary efficacy endpoint was proportion of patients with a ≥ 13-point improvement from baseline to day 42 in FIQR score. Secondary efficacy endpoints included changes from baseline to each time point in FIQR scale total score, BPI total score, MOS Sleep scale score, and Fatigue VNS score; and change from baseline in iron indices (e.g., transferrin saturation, ferritin) at each time point. The BPI total score was the sum of scores from the two domains of Pain Severity and Pain Interference. Safety endpoints included incidence of AEs and serious AEs, changes in clinical laboratory test values, and changes in vital signs.

Statistical Analysis

The efficacy evaluable population (used for all efficacy analyses) comprised all patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study medication and completed ≥ 1 post-treatment FIQR evaluation. For the primary efficacy analysis, the FIQR was divided into three domains: Function, Overall Impact, and Symptoms. Each domain comprised a cluster of items graded on a 0–10 numeric rating scale. The Function domain had nine items, the Overall Impact domain had two items, and the Symptoms domain had ten items. A lower score indicated a better quality of life. If three or more questions were unanswered, the questionnaire was considered invalid and the total score was set to null. If fewer than three questions were unanswered, scores were weighted to calculate domain scores; the added score of the completed questions was weighted by the total number of items in the domain divided by the number completed in the domain. The total FIQR score was calculated from the three normalized domain scores: (function domain score/3) + (overall impact domain score/1) + (symptoms domain score/2). Patients who discontinued or did not complete the study were considered nonresponders. The statistical test for the primary endpoint was performed with a type I error of 0.05, two-tailed. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons for other endpoints; thus, the P values for those treatment comparisons are considered descriptive and not inferential. Treatment group differences for proportions were assessed with the Chi square test, and treatment group differences for means were assessed with the analysis of covariance with fixed factor for treatment and baseline score as covariate. The safety evaluable population (used for all safety analyses) comprised all patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study treatment. Analyses of safety data were descriptive and were not subjected to formal statistical comparisons.

With the assumption that the proportion of responders with ≥ 13-point improvement from baseline in FIQR score would be 30% in the placebo group, a sample size of 40 patients per group provided a 78% power to detect a 2.0-fold increase in the responder rate (i.e., 30 vs. 60%) and > 95% power to detect a 2.5-fold increase in the responder rate (i.e., 30 vs. 75%).

Results

Patient Disposition and Demographics

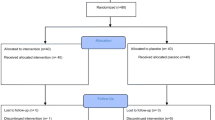

Of 168 patients screened, 87 were screen failures [85 failed because of exclusionary iron indices (TSAT and/or ferritin), one withdrew consent, and one had difficulty with phlebotomy] and 81 patients were randomized and received ≥ 1 dose of ferric carboxymaltose (n = 41) or placebo (n = 40). All 81 patients were evaluable for safety, and 80 were evaluable for efficacy; one patient in the ferric carboxymaltose group did not complete a post-treatment FIQR and was excluded from the efficacy analysis. Two patients were discontinued from the study; one patient in the ferric carboxymaltose group was lost to follow-up, and one patient in the placebo group had a difficult phlebotomy during study drug administration on day 5.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1). The majority of patients were female (99%) and had no history of iron intolerance (89%). Concomitant medical conditions at baseline included depression (53%), hypertension (43%), iron-deficiency anemia (40%), anxiety (36%), and tubal ligation (35%). No patient required intervention for fibromyalgia during the study.

Efficacy

Patient-Reported Outcomes

The percentage of patients with a ≥ 13-point improvement in FIQR score from baseline to day 42 was greater in the ferric carboxymaltose group than the placebo group (76.9 vs. 66.7%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.314). Sensitivity of the treatment difference to alternative improvement criteria is illustrated in Fig. 1. The percentage of patients achieving the 13-point improvement criterion is depicted for each treatment group at the vertical line. The figure demonstrates that regardless of the definition of responders based on improvement from baseline (10–80 points), patients receiving ferric carboxymaltose achieved greater improvement compared with those receiving placebo.

Mean improvements from baseline in FIQR total score were significantly (P ≤ 0.015) greater in patients treated with ferric carboxymaltose than in those treated with placebo on assessment days 14 (− 33.8 vs. − 17.1, respectively), 28 (− 45.2 vs. − 25.0, respectively), and 42 (− 45.0 vs. − 29.7, respectively) (Table 2). The correlation between baseline IRLS score and change in FIQR total score from baseline to day 42 was not significant in either treatment group (Pearson coefficient: r = − 0.162, P = 0.331 ferric carboxymaltose; r = 0.001, P = 0.994 placebo). Mean improvements from baseline in FIQR components are summarized in Table 3. Significantly (P ≤ 0.022) greater improvements from baseline were observed in the ferric carboxymaltose group vs. the placebo group for mean BPI Pain Severity score on days 14 (− 2.3 vs. − 0.9, respectively), 28 (− 3.0 vs. − 1.3, respectively), and 42 (− 3.1 vs. − 1.8, respectively) and BPI Pain Interference score on days 14 (− 3.2 vs. − 1.0, respectively), 28 (− 4.1 vs. − 1.8, respectively), and 42 (− 4.1 vs. − 2.3, respectively) (Table 2). Mean changes from baseline in MOS Sleep scale scores were similar between the ferric carboxymaltose and the placebo groups on each assessment day (day 14: − 9.2 vs. − 6.6; day 28: − 12.1 vs. − 9.6; day 42: − 13.6 vs. − 9.5, respectively) (Table 2), with no statistically significant differences. Compared with placebo, ferric carboxymaltose significantly (P ≤ 0.005) improved the Fatigue VNS mean score on days 14 (− 2.5 vs. − 1.3, respectively), 28 (− 3.2 vs. − 1.6, respectively), and 42 (− 3.7 vs. − 1.7, respectively) (Table 2).

Iron Indices and Hematologic Parameters

Ferric carboxymaltose significantly increased serum ferritin and transferrin saturation from baseline to day 42 compared with placebo (P < 0.001 for each) (Table 2). Hemoglobin and hematocrit from screening to day 42 showed mean increases in the ferric carboxymaltose group but decreases in the placebo group (Table 2).

Safety

A larger percentage of patients in the ferric carboxymaltose group (29.3%) than in the placebo group (5.0%) reported ≥ 1 treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE). TEAEs reported by ≥ 2 patients in the ferric carboxymaltose group included flushing (14.6%), nausea (7.3%), and dizziness (4.9%). No TEAE in the placebo group was reported by ≥ 2 patients.

At least one drug-related TEAE was reported by 24.4% of patients in the ferric carboxymaltose group; no patients in the placebo group reported a drug-related TEAE. There were no serious TEAEs, and none led to discontinuation of study medication. During the study, none of the patients had drug-related TEAEs of hypersensitivity, allergic reaction, hypotension, or hypertension.

Discussion

In the current study, the effect of IV ferric carboxymaltose vs. placebo was evaluated in patients with iron deficiency (baseline ferritin: ≥ 0.05 µg/ml; transferrin saturation: ≥ 20%) and fibromyalgia. More patients treated with ferric carboxymaltose (77%) than placebo (67%) achieved a ≥ 13-point improvement in FIQR mean total score from baseline to day 42; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Although the primary endpoint of the study was not met, greater mean improvements were observed in FIQR total score, BPI Pain Severity and Interference scores, Fatigue VNS score, and iron indices in patients treated with ferric carboxymaltose compared with those who received placebo. Mean changes in MOS Sleep scale score were similar between the two groups.

Correlative evidence from clinical studies suggests a possible association between iron deficiency and fibromyalgia. A case–control study by Ortancil and colleagues [8] reported significantly lower mean serum ferritin levels in women with fibromyalgia compared with healthy women (27 ± 21 vs. 44 ± 31 mg/ml; P = 0.003) who were well matched by age, body mass index (BMI), hemoglobin, serum vitamin B12, and folic acid levels. Analysis of the data by binary multiple logistic regression demonstrated that a serum ferritin level < 0.05 µg/ml was linked to a 6.5-fold increased risk of fibromyalgia (P = 0.002), which decreased to 5.9-fold risk (P = 0.011) after exclusion of patients with restless legs syndrome and depression. In an analysis of hair minerals, Kim and colleagues [9] reported significantly lower levels of iron in patients with fibromyalgia compared with healthy age- and BMI-matched controls (P = 0.007). Pamuk and colleagues [10] found an increased prevalence of fibromyalgia in patients with iron-deficiency anemia (P = 0.006) and thalassemia minor (P = 0.025) compared with healthy controls. These studies suggest that iron therapy may have a role in the management of fibromyalgia. The present study supports the assertion that IV iron supplementation demonstrates significant improvements in multiple indices of pain and fatigue often used in measuring symptoms of fibromyalgia.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with a ≥ 13-point improvement in FIQR score from baseline to day 42. Compared with responder rates specified for the sample size calculation, the rate for ferric carboxymaltose was near the prespecified 60–75%, whereas the placebo rate of 67% was more than twice the prespecified 30%, indicating a high placebo response in the current study. In addition, the cumulative distribution curve of the percent of patients who achieved a designated degree of improvement in FIQR total score provides insight into the discrepancy between tests of the proportions based on a 13-point improvement and the test for mean change from baseline (Fig. 1). The smaller than predicted difference between treatment groups in proportions was consistent across potential improvement criteria, leading to a substantial difference in the means. When this occurred, the power of the test for means was substantially larger than that for proportions. In future studies, it may be more appropriate to define the mean change from baseline in FIQR score as the primary efficacy endpoint and the responder rate as a secondary endpoint.

A key limitation of the study was that the primary efficacy parameter was not met. However, greater improvements were observed for other symptoms of fibromyalgia along with indices of iron deficiency.

Conclusions

In conclusion, treatment with ferric carboxymaltose appears to have improved symptoms of fibromyalgia, as measured by FIQR total scores, BPI total score (Pain Severity plus Pain Interference score), and Fatigue VNS scores, as well as laboratory iron indices, in patients with fibromyalgia who had demonstrable depletion of total-body iron stores as evidenced by low ferritin and low transferrin saturation. Ferric carboxymaltose was well tolerated and safe in the current study and may warrant further study as a treatment for fibromyalgia.

References

Boomershine CS. Fibromyalgia: the prototypical central sensitivity syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2015;11:131–45.

Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1547–55.

Jones GT, Atzeni F, Beasley M, et al. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population: a comparison of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 2010, and modified 2010 classification criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:568–75.

Vincent A, Lahr BD, Wolfe F, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:786–92.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–10.

Russell IJ, Vaeroy H, Javors M, Nyberg F. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites in fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:550–6.

Legangneux E, Mora JJ, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Thorin I, Herrou M, Alvado G, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites, plasma-rich platelet serotonin and [3H]imipramine reuptake in the primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:290–6.

Ortancil O, Sanli A, Eryuksel R, Basaran A, Ankarali H. Association between serum ferritin level and fibromyalgia syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:308–12.

Kim YS, Kim KM, Lee DJ, et al. Women with fibromyalgia have lower levels of calcium, magnesium, iron and manganese in hair mineral analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1253–7.

Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON, Set T, et al. An increased prevalence of fibromyalgia in iron deficiency anemia and thalassemia minor and associated factors. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:1103–8.

Friedman AJ, Chen Z, Ford P, et al. Iron deficiency anemia in women across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1282–9.

Jimenez K, Kulnigg-Dabsch S, Gasche C. Management of iron deficiency anemia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;11:241–50.

Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31–8.

Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1832–43.

Lyseng-Williamson KA, Keating GM. Ferric carboxymaltose: a review of its use in iron-deficiency anaemia. Drugs. 2009;69:739–56.

Toblli JE, Angerosa M. Optimizing iron delivery in the management of anemia: patient considerations and the role of ferric carboxymaltose. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2475–91.

Injectafer [package insert]. Shirley, NY: American Regent, Inc.; July 2013.

Koduru P, Abraham BP. The role of ferric carboxymaltose in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with gastrointestinal disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:76–85.

Cho YW, Allen RP, Earley CJ. Clinical efficacy of ferric carboxymaltose treatment in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2016;25:16–23.

Yunus MB, Aldag JC. Restless legs syndrome and leg cramps in fibromyalgia syndrome: a controlled study. BMJ. 1996;312:1339.

Walters AS. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634–42.

Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, et al. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R120.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1113–22.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the patients who participated in the study and the staff at Clinical Research Solutions for their hard work and dedication. Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were provided by Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Lisa Feder, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Chad Boomershine has participated on an advisory board for a muscle relaxer for Vertical Pharmaceuticals, LLC, has participated on an advisory board and speakers’ bureau for an analgesic medication for Pfizer Inc., and has been compensated for his work on the current study by Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., through Clinical Research Solutions. Todd A. Koch is an employee of Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc. David Morris is an employee of WebbWrites, LLC, a company providing services to the pharmaceutical industry, including Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc. There are no financial interests in individual pharmaceutical companies to declare, apart from possible mutual fund holdings.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the United States Code of Federal Regulations on Protection of Human Subjects (21 CFR 50), institutional review board regulations, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, 21 CFR Part 312, and applicable International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines, as well as local and state regulations. All study participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Content

To view enhanced content for this article go to www.medengine.com/Redeem/63DCF06009D398B6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Boomershine, C.S., Koch, T.A. & Morris, D. A Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study to Investigate the Efficacy and Safety of Ferric Carboxymaltose in Iron-Deficient Patients with Fibromyalgia. Rheumatol Ther 5, 271–281 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0088-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0088-9